15 Apr 2016

In this blog, Charlotte Marriott talks about conserving a collection of eighteenth century ship plans. This is an ongoing project, which a number of Conservators from the National Maritime Museum and Paper Conservation MA students from the University of the Arts have worked on over the last few years.

Whilst studying to become a conservator, I completed a placement one day a week for six months in the Paper Conservation Department of the National Maritime Museum. With such a varied collection, I was fortunate to see and work on lots of different objects. In this blog, I’m going to explain how I went about conserving a collection of ship plans called the Hilhouse Collection.

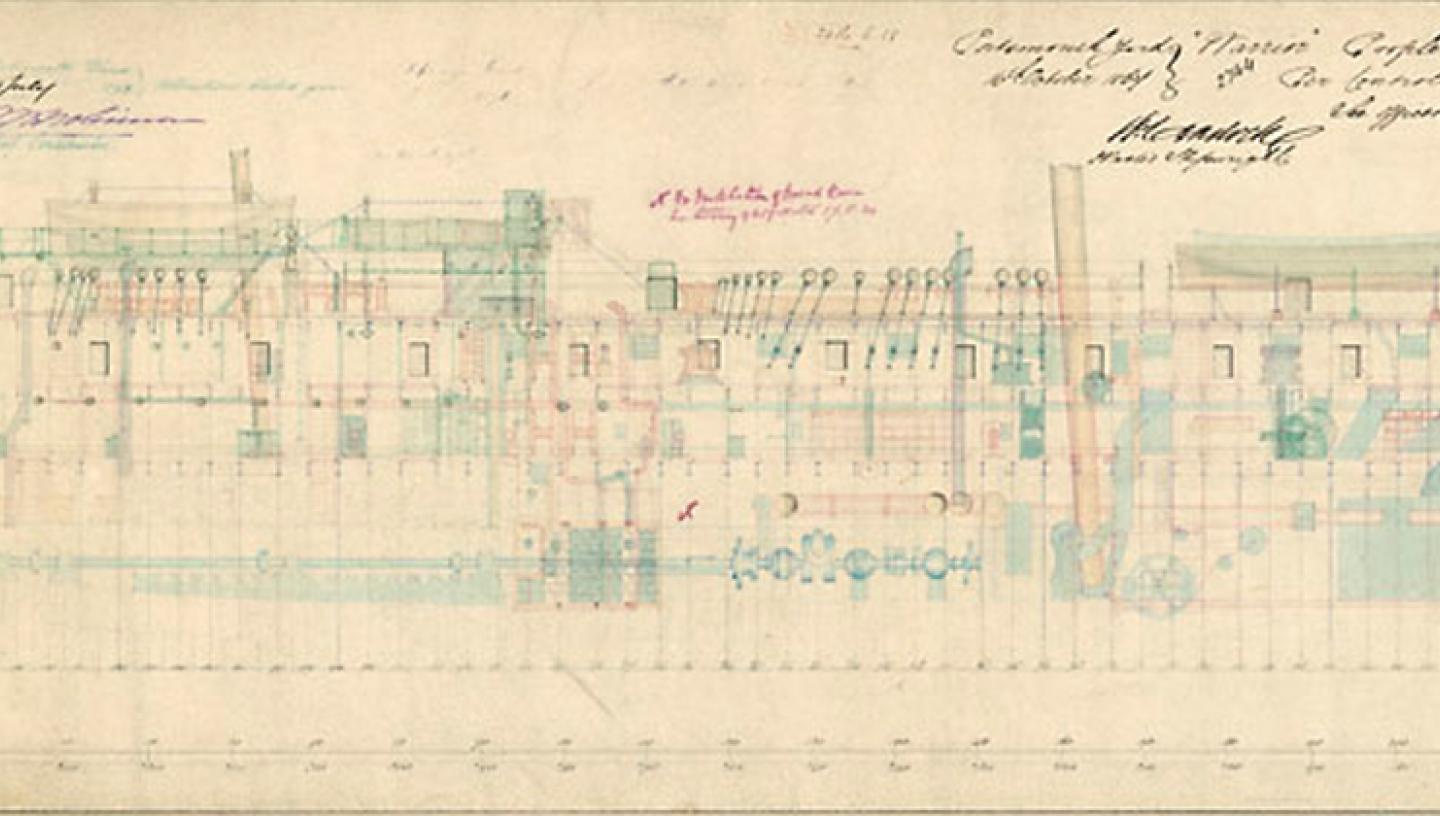

The Hilhouse collection is an assortment of over 150 merchant ships’ plans, dating from the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century. The plans belonged to a ship building company called Hilhouse & Sons that was based in Bristol from the 1770’s until the 1970’s.

Some ship plans were repaired whilst still in use in the yard and others have been conserved since their acquisition by the National Maritime Museum in the 1970s. Others have never been worked on.

So, it is a fascinating collection in terms of understanding two hundred years of paper repairs! For instance, some of the very early repairs used wood pulp paper that can turn yellow and brittle quite quickly. Various adhesives, from flour paste to animal glues were used that are hard to remove. Now there is now greater emphasis on using acid-free and lignin-free papers, which will degrade much slower. In paper conservation, we use a lot of hand made papers from China and Japan. Conservators aim to use treatments and repairs which are reversible, for instance using water soluble adhesive formed from wheat starch.

However, there comes a time when the old repair has been part of the object so long that it is now part of its history. All treatments come with a certain amount of risk and conservators base all treatment decisions on conservation ethics, which helps to maintain works for future generations. We have to think if removing a historic repair might risk changing the object irrevocably. Primarily, my role was to stabilise as many plans as possible, in order to increase accessibility to the collection.

In terms of damage, the collection is relatively dirty, from its heavy use in the shipyard.

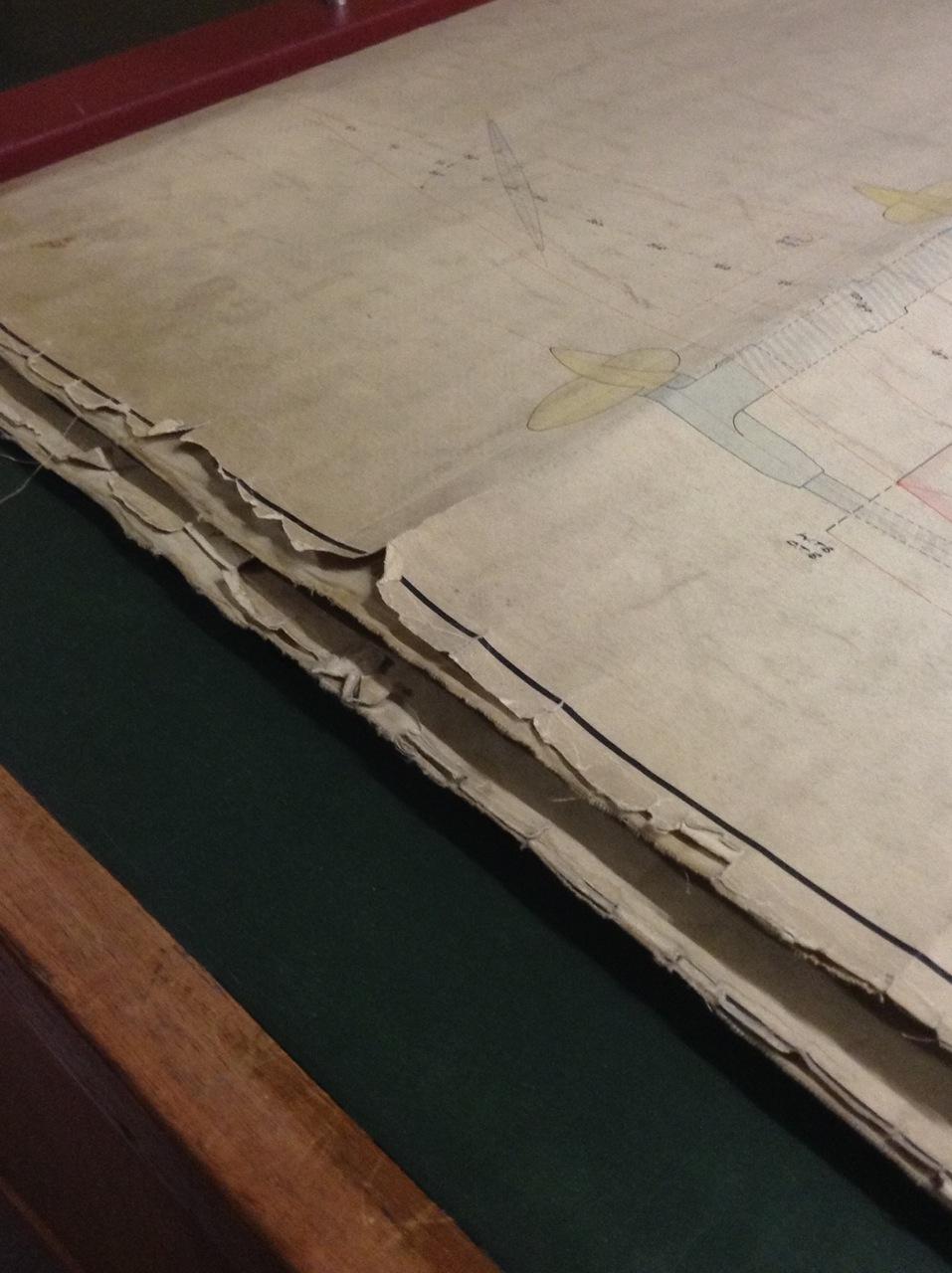

All the plans in this collection are now kept flat, but years of folding and unfolding, rolling and unrolling have left folds and ripples in the paper. Some of the plans are torn or have sections missing, which is unsurprising as they were part of a working collection and some of the plans are huge, measuring over 2m in length! In some extreme cases, the plans have been completed on separate sheets, which have now split apart.

All of the plans that I conserved were first cleaned by hand, with soft bristled brushes and chemical sponge (a synthetic type of soft eraser). The more problematic engrained dirt was removed with the gentle application of a non-silicon eraser. I had to be very careful not to crease the delicate paper, or rub off the graphite in the plans. To relax the cellulose fibres in the paper, a low concentration of water was introduced into the paper. Not only does this make paper easier to press but also the adhesive sticks more easily when repairing tears and losses. With the paper relaxed, there is less risk of stress lines appearing as the glue dries.

During humidification, the plans were placed in a chamber, into which mist from an Ultra-Sonic Mister was pumped. This heightened the relative humidity of the atmosphere in the chamber and humidified the paper. If the plans needed no further treatment, they were sandwiched between a synthetic non-stick material called bondina, thick paper blotters and felts, weighted down by wooden boards and metal weights, to dry and flatten for a few hours.

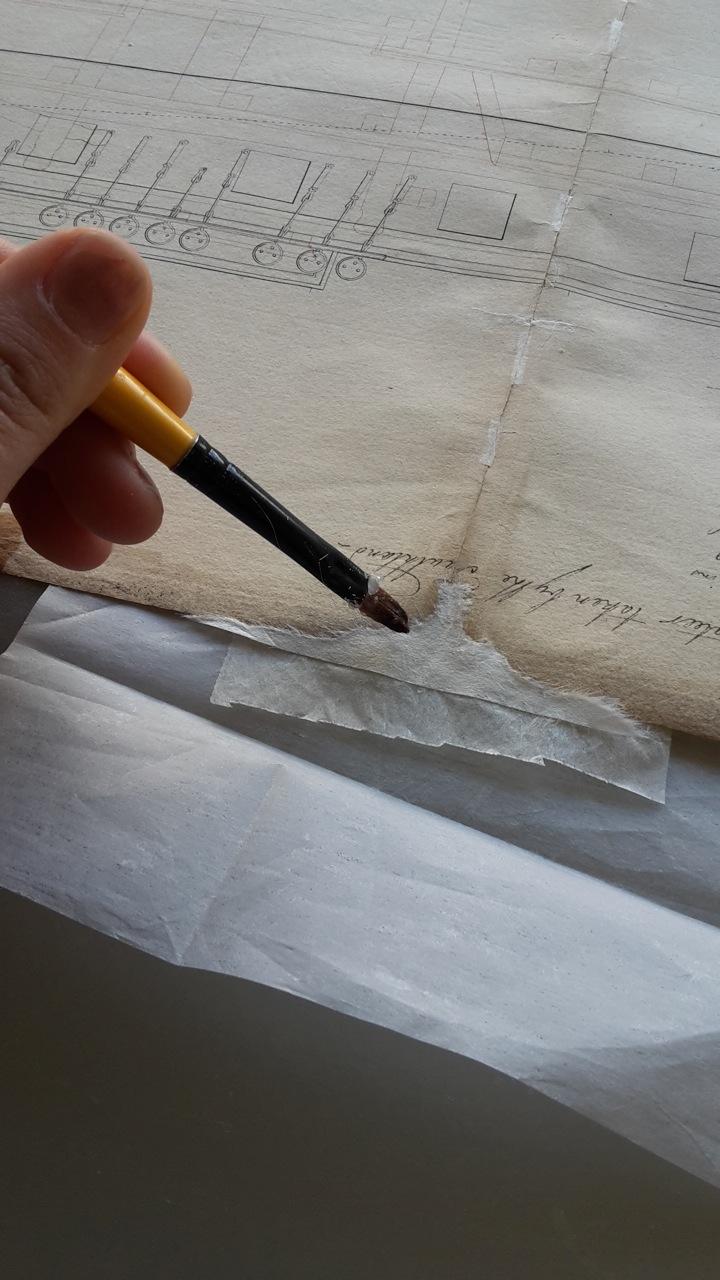

If the plans were torn, Japanese tissues were used to re-adhere it back together. Japanese Kozo tissue is made from the mulberry plant. This plant has long fibres, which form incredibly thin but strong sheets of paper. With archival repairs, the structural strength rather than aesthetic appearance of the object has paramount importance. However, I tried to overlap different tissues to match the original colour, weight and texture of the ship plan paper. All tissues were adhered with wheat starch paste. The flour is cooked in water into very thick and sticky glue then diluted with water into a flexible paste.

The plans had been rendered in graphite, paints and inks that are extremely water sensitive. Not only could moisture make the media run, but moisture speeds up the degradation of the inks and risks the paper falling apart in these areas. When repairing areas of damage where there ink was present, I used re-moistenable tissues. These tissues are already coated in glue, and it only requires a small amount of water to rehydrate the adhesive.

The key challenge I discovered in treating the plans was working on several large plans at once. As many treatments are time consuming and drying times for the plans quite long, it makes sense to work on more than one thing at the same time. However, that means organising your workspace very well and estimating the time taken for each treatment, to use time in the studio most effectively.

In the next blog of this series, I will talk about how I researched this collection, to understand more about the history of eighteenth century ship design.

Find out more about our ship plans collection