20 Sep 2017

The recent discovery of Frankin's lost ships reveals more than artefacts and history. Amber Lincoln of the British Museum discusses the impact of Inuit oral history on locating the ships and what this means for the future of research in the Arctic.

by Amber Lincoln, British Museum

Inuit history guiding the way

The discovery of the wreckage of the two ships from Sir John Franklin’s lost 1845 voyage reveals more than artefacts and history. Western science and exploration technologies directed by Inuit observation and oral history led to the discovery of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror over 160 years after the disastrous events leading to the end of the Franklin expedition. While the recovery of the wreckage will certainly help to piece together the history of the expedition, the process of discovering that wreckage – combining two knowledge systems, Western Science and Inuit Knowledge (Qaujimajatuqangit) – offers a compelling example of integrated research.

Read more about Qaujimajatuqangit and the Franklin expedition search on the Parks Canada website

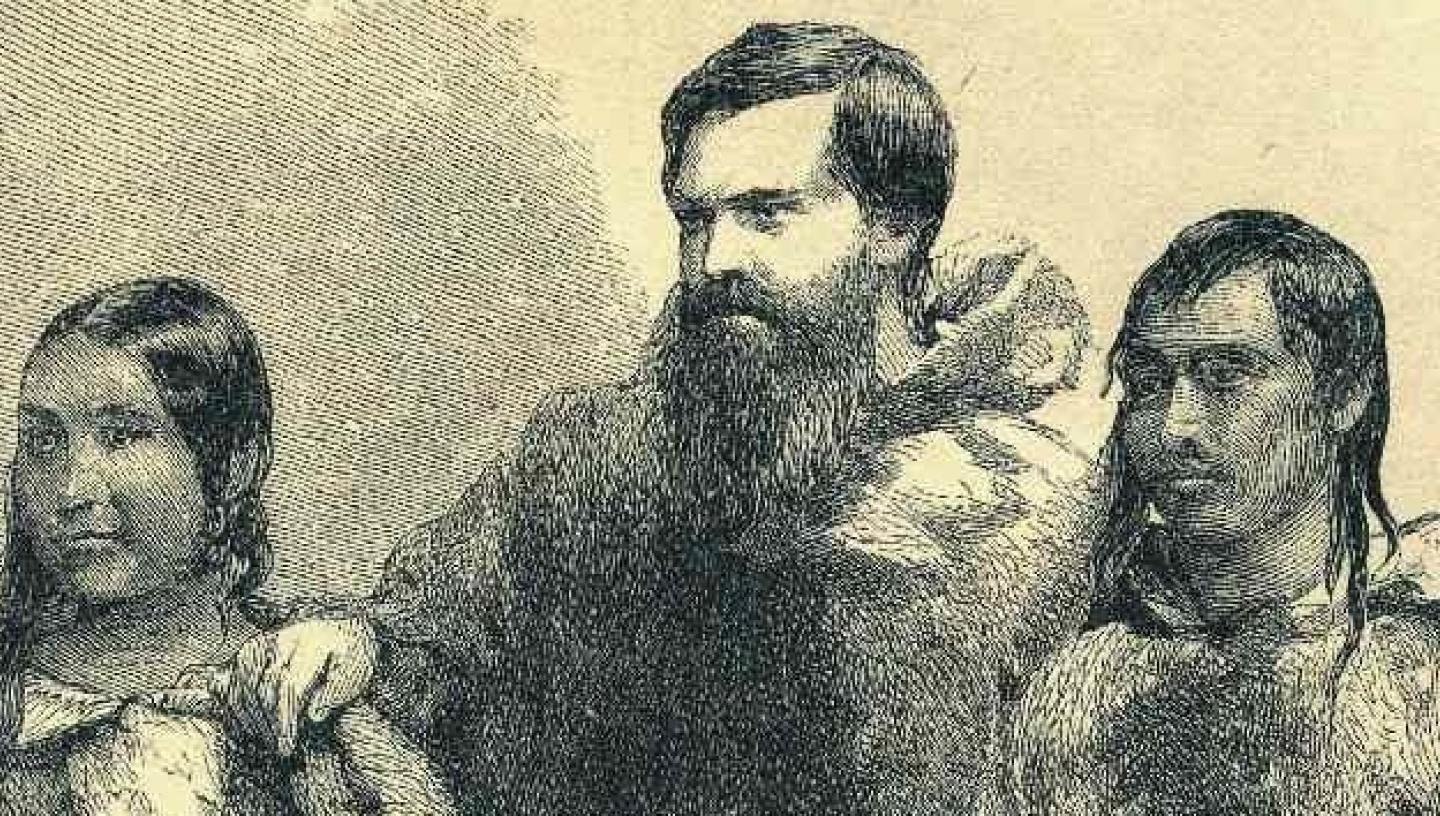

The Netsilik Inuit of King William Island have passed down stories from one generation to the next about the Franklin expedition and the resulting tragedy. These stories directed the Parks Canada team of explorers and archaeologists in their search for the wreckage, leading to the discovery of Erebus in 2014.

Gjoa Haven resident Louie Kamookak, in particular was critical to this effort. He recorded Inuit stories for over 30 years, piecing together a theory of the ships’ locations. In 2016, Gjoa Haven resident Sammy Kogvik told the team where he has seen wood sticking up through sea ice six years earlier. Following Kogvik’s observation, the team very quickly found Terror. Oral history and keen observation from Inuit were critical to these discoveries.

Knowledge passed from generation to generation

The precision of knowledge maintained in Inuit oral histories used to locate the remains of the Franklin expedition is exciting but not surprising. Relaying information and events across generations has been essential for the success of Inuit culture throughout the Arctic. Louis Kamookak explained in 2015,

"Inuit had no written system of language... History was passed down through oral history, which meant telling and retelling stories. During the long winter days and nights it was usually the elders who would tell stories."(Ref: louiekamookak.com)

Inuit often tell stories about events that they observed or participated in. In other cases, they retell stories they have heard from others. In those cases, the narrator gives a genealogy of storytellers leading to his or her version. This not only credits the storytellers before oneself, but also situates the story within the context of an individual’s life, providing contextual information and some social resistance to embellishments or altered interpretations.

Many stories are remembered through place names. Again Kamookak explains, ‘Inuit place names is one way of passing down history to the next generation…There’s a story behind every Inuit place name’.

Read about the Kitikmeot Heritage Society’s place name project

While stories and oral histories are told to preserve important and sometimes life-saving information, they are also narrated and performed for enjoyment. Inuit appreciate good storytellers. Their skills are esteemed both for their performance and their consistency with events. Isuma Productions is a media corporation that brings Inuit stories to the world. Inuit practices of storytelling (such as place names, situating stories in the context of lives) and the value Inuit place on these practices fosters precision as stories are told and retold across generations.

Inuit knowledge and climate change

A growing number of scientists and policy makers value Inuit knowledge. Following leadership of the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the Nunavut government, scientists and local Inuit are working together to understand ecosystems of the circumpolar north. In particular, science combined with Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is effectively monitoring the changing atmospheric conditions, shifting ranges and populations of animals and plants and increasing coastal erosion as impacts of global climate change. Accurate and early detection of these impacts is critical for northern communities as they try to plan for their future. A number of exciting projects demonstrate the contributions Inuit make to climate change research and global awareness. Read about two of these projects:

Voices From the Land Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada