17 May 2017

May 18th is International Museum Day, and this year the theme is Contested Histories. As part of the development of the new Tudor & Stuart Seafarers gallery (opening 2018 in the Exploration Wing), the National Maritime Museum is exploring multiple perspectives on the early history of North America. James Davey and Laura Humphreys explain the process behind incorporating Indigenous American voices into the gallery.

In late February and early March 2017, we visited the United States to conduct research for a new gallery at the National Maritime Museum entitled ‘Tudor and Stuart Seafarers’. This display will tell the story of how England, and later Britain, emerged as a maritime nation in the early modern era, covering important themes like exploration, trade, piracy and warfare. This gallery reveals the many ways English expansion impacted upon peoples around the world, and won't shy away from difficult and contested histories. A key section of the gallery will focus on the history of ‘Encounter and Exploitation’ between Europeans and Native American peoples, and so we made our own expedition to the United States to find out how museums there had told this story.

Out first aim was to visit as many museums as possible, and to meet with experienced colleagues working in Indigenous American histories. Chief among them was the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC. As the first national museum devoted to telling the story of Indigenous Americans, it covers the history of the American hemisphere from Indigenous perspectives, with exhibition topics ranging from the Great Inca Road to twentieth-century Indigenous photography.

The NMAI uses a variety of approaches. One floor was devoted to co-curated displays in which tribal people from across the American continent had created small displays relating to their own practices and cultures; another floor focuses on the history of treaties (the legal agreements between Native nations and the United States). It is striking how difficult it is to create displays which cater to many audiences, from Indigenous peoples themselves to non-expert visitors who know very little of this history.

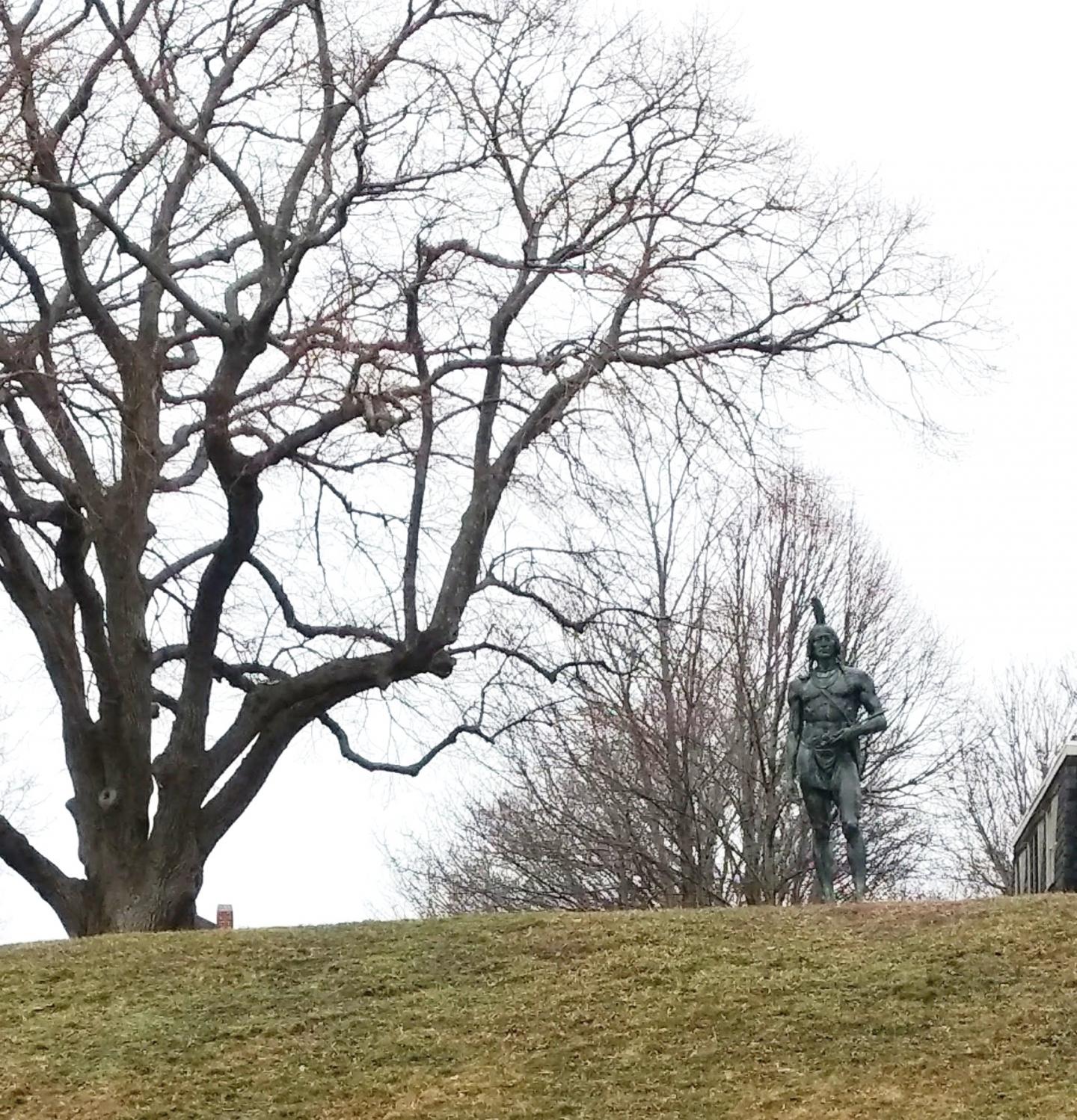

We visited numerous other museums, but the real highlight of the trip was two days spent with Wampanoag community of Mashpee, Massachusetts. The Wampanoag people are from the Cape Cod area of Massachusetts, and were one of the first to encounter English explorers, not least the Pilgrims who crossed the Atlantic in 1620 in the Mayflower. They are a prominent Indigenous group in the contemporary United States, and we were fortunate to visit ‘Plimoth Plantation’, a living history museum that places the story of the Pilgrims alongside that of the Wampanoag, and plays an active role in teaching visitors to Plimoth about historic and contemporary Wampanoag culture.

Thanks to the assistance of the Plymouth 400 project, we visited the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Centre, where we met representatives from the tribal community's historic preservation office, and talked to them about our plans for the gallery. It was a rewarding experience to hear people talking frankly about issues of Wampanoag identity, and how best to represent their community for British audiences. Many felt that it is important to address the difficult (and recent) past, but also that people need to know the 400 years since Europeans arrived is just one small part of the Wampanoag story.

One of the most important outputs from the trip was an agreement that the Tudor and Stuart Seafarers gallery will contain a video installation, with content developed and delivered by Wampanoag people. Objects in museum collections, (particularly from such an early period) tend to tell a very one-sided, Eurocentric version of global histories. To address this, we want the Wampanoag to present their own points of view on early European arrivals in America. At our meeting in the Tribal Centre, a myriad of options were discussed: whether to foreground the appalling violence and exploitation directed at Indigenous Americans; to focus on the complex societies and cultures that existed prior to contact with Europeans; or to the contemporary legacies of this history.

We hope that this will ensure that this contested history is told in the right way on this side of the Atlantic, and that our relationship with our Wampanoag colleagues will continue. There are many great maritime stories to be told about our shared seafaring pasts.