The history of the transatlantic slave trade

Find out about the slave trade, resistance and eventual abolition at the Atlantic gallery.

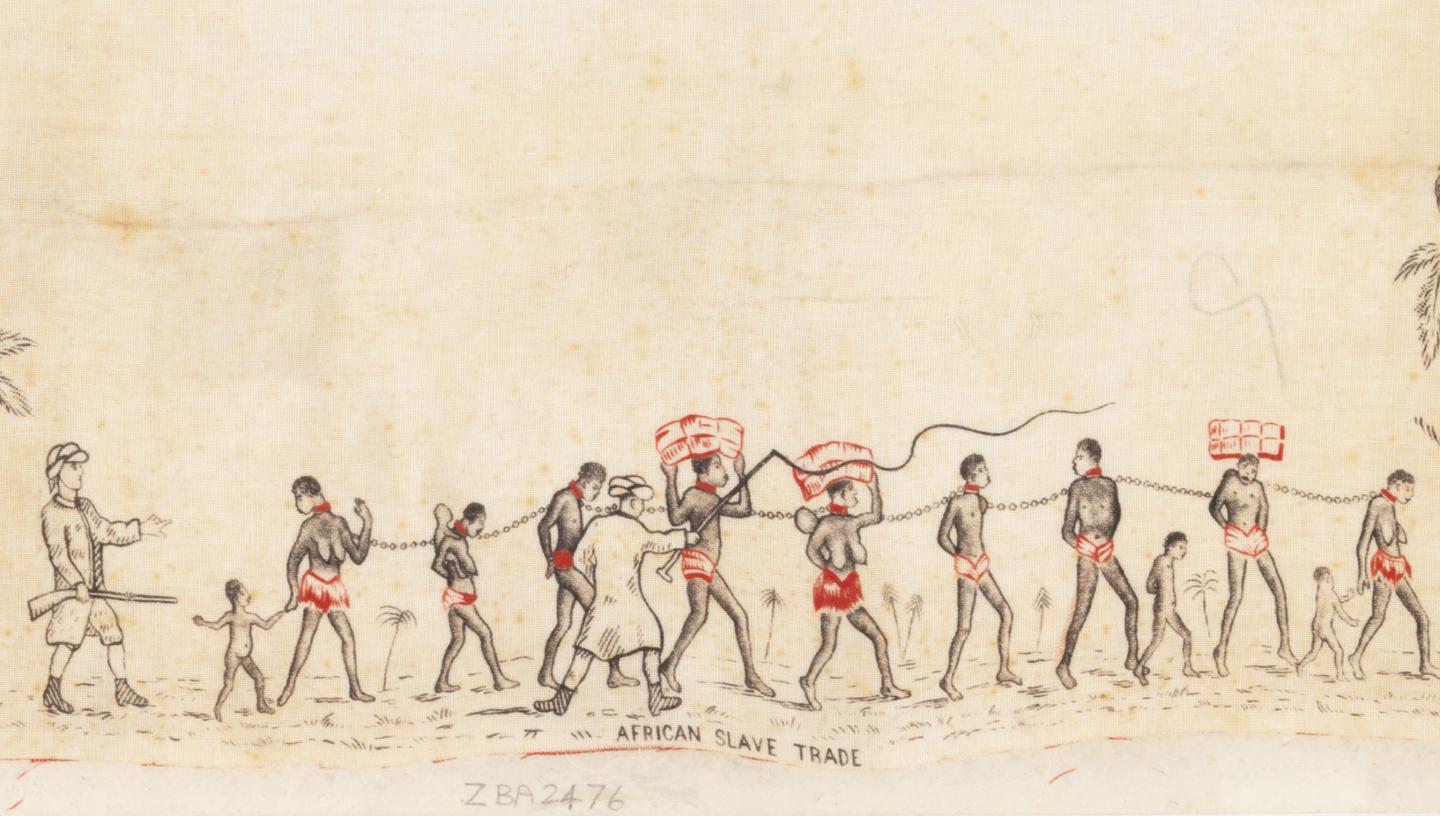

Africa and Enslavement

Ivory, gold and other trade resources attracted Europeans to West Africa. As demand for cheap labour to work on plantations in the Americas grew, people enslaved in West Africa became the most valuable ‘commodity’ for European traders.

Slavery existed in Africa before Europeans arrived. However, their demand for slave labour was so great that traders and their agents searched far inland, devastating the region. Powerful African leaders fuelled the practice by exchanging enslaved people for goods such as alcohol, beads and cloth.

Britain became the world’s leading slave-trading country. Transatlantic slavery was especially lucrative because ships could sail with full holds on every stage of their voyage, making large profits for merchants in London, Bristol and Liverpool.

Around 12 million Africans were enslaved in the course of the transatlantic slave trade. Between 1640 and 1807, British ships transported about 3.4 million Africans across the Atlantic.

The Middle Passage

The ‘Middle Passage’ was the harrowing voyage experienced by the millions of African captives transported across the Atlantic in European ships, to work as slaves in the Americas. Conditions on board slave ships were appalling: huge numbers of people were crammed into very small spaces. Men, women and children were separated, families being torn apart.

Overcrowding, poor diet, dehydration and disease led to high death rates. 450,000 of the 3.4 million Africans transported in British ships died on the Atlantic crossing. Those who resisted by refusing food and water were beaten and force-fed. Attempts at more violent, organised rebellion were even more savagely punished. Some people preferred death to slavery and committed suicide during the voyage or later.

Visions of the Caribbean: plantation conditions

By the 16th century, Europeans had started to develop and cultivate regions in the Caribbean, North and South America. As demand for labour grew, Europeans turned to West Africa to supply an enslaved workforce.

These people were defined in law as ‘chattels’ – the personal property of their ‘owners’ – and were denied the right to live and move as they chose. Their forced labour produced commodities like tobacco, cotton and sugar, for which there was a huge European demand.

Nearly two-thirds of all enslaved people cut cane on sugar plantations. These were places of hard labour and cruel treatment with very high mortality rates. Despite this, African music, dance and religious ceremonies flourished, evolving into new hybrid cultures and traditions.

Visions of the Caribbean: resistance

Enslaved people fought to retain their families, cultures, customs and dignity. Resistance took many forms: from keeping aspects of their identity and traditions alive to escaping and plotting uprisings.

On the plantations they broke tools, damaged crops and feigned injury or illness in order to frustrate plantation owners and their ambitions for greater profits. At other times, they made bids for freedom by escaping. Sometimes these ‘runaways’ grouped together and built their own independent, self-sufficient communities of resistance, often known as ‘maroons’.

Large-scale organised uprisings were a common reaction to the cruelties of the slave system. Potential and actual armed resistance also contributed to the ending of the slave trade and eventually slavery itself.

How did the slave trade develop in Britain?

Elizabeth I believed that capturing Africans against their will 'would be detestable and call down the vengeance of Heaven upon the undertakers', yet after seeing the huge profits available she lent Royal Ships to two slaving expeditions of John Hawkins – the first English trader of enslaved people from West Africa to the Americas.

No English settlements were established in North America or in the West Indies during the reign of Elizabeth, but in the 17th century the English began to acquire territory in the New World. The English colonies expanded rapidly and the development of a plantation system and the growth of the Atlantic economy brought further demands for African labour. This increased the scale of the trade in enslaved people.

In the first third of the 18th century, Britain’s involvement in the slave trade grew enormously. In the 1710s and 1720s, nearly 200,000 enslaved Africans were transported across the Atlantic in British ships.

Abolitionism in Britain

Abolitionism was one of Britain’s first lobbying movements. The first meeting of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade took place in London in May 1787. African writers and activists such as Olaudah Equiano spoke out against the trade and its inhumane treatment of Africans. High-profile figures such as William Wilberforce MP, and Thomas Clarkson also used their influence to effect its abolition.

Abolitionists argued that, in addition to stopping an immoral practice, ending the slave trade would save the lives of thousands of European sailors and open new markets for British goods. But their pro-slavery opponents pointed out how important Caribbean plantations were to Britain’s economy.

Parliament finally passed an Act to abolish the slave trade in 1807. It stated that all slave trading by British subjects was ‘utterly abolished, prohibited and declared to be unlawful’. But it did not end the institution of slavery itself and nearly 750,000 people remained enslaved in British colonies across the Caribbean.

Mobilizing public support

Abolitionists succeeded in mobilizing unprecedented public support. Through a campaign of information they demonstrated what lay behind the sugar, tobacco and coffee enjoyed by Britons. People signed petitions, attended lectures and abstained from eating West Indian sugar.

Many people who signed petitions could not vote and this was their only means of expressing their opinion to Parliament. Over 100 petitions against the slave trade were submitted to Parliament in 1788, rising to 519 in 1792. For the first time in a public political campaign, women were extensively involved, adding their voices to the calls for abolition.

The continuation of slavery

Although the British Parliament outlawed slavery in 1807, a quarter of all Africans who were enslaved were transported across the Atlantic after this date. In British colonies, the institution of slavery carried on as before, until Parliament passed an Emancipation Act in 1833. This was achieved by a combination of active resistance in the Caribbean and campaigning in Britain. Even then, full emancipation was not realized until 1838 when a period of unpaid labour ended and 800,000 people were freed across the British Caribbean. But Parliament also voted to pay the plantation owners £20 million in compensation. No payment was made to the ex-slaves.

After 1807: the Royal Navy and suppression of the slave trade

In 1808, the British West Africa Squadron was established to suppress illegal slave trading. Between 1820 and 1870, Royal Navy patrols seized over 1500 ships and freed 150,000 Africans destined for slavery in the Americas.

Many people believed that the only way to eradicate slavery was to promote ‘legitimate’ trade and European forms of religion and government in Africa. This paved the way for colonial rule later in the 19th century.