13 Jul 2017

Many of the common seamen of Nelson’s time were not literate, meaning letters of the ‘Lower deck’ are rare. Nelson probably received a great deal of correspondence asking for help or influence of one kind or another, but was his reputation for benevolence towards those that had served under him sometimes exploited or taken advantage of?

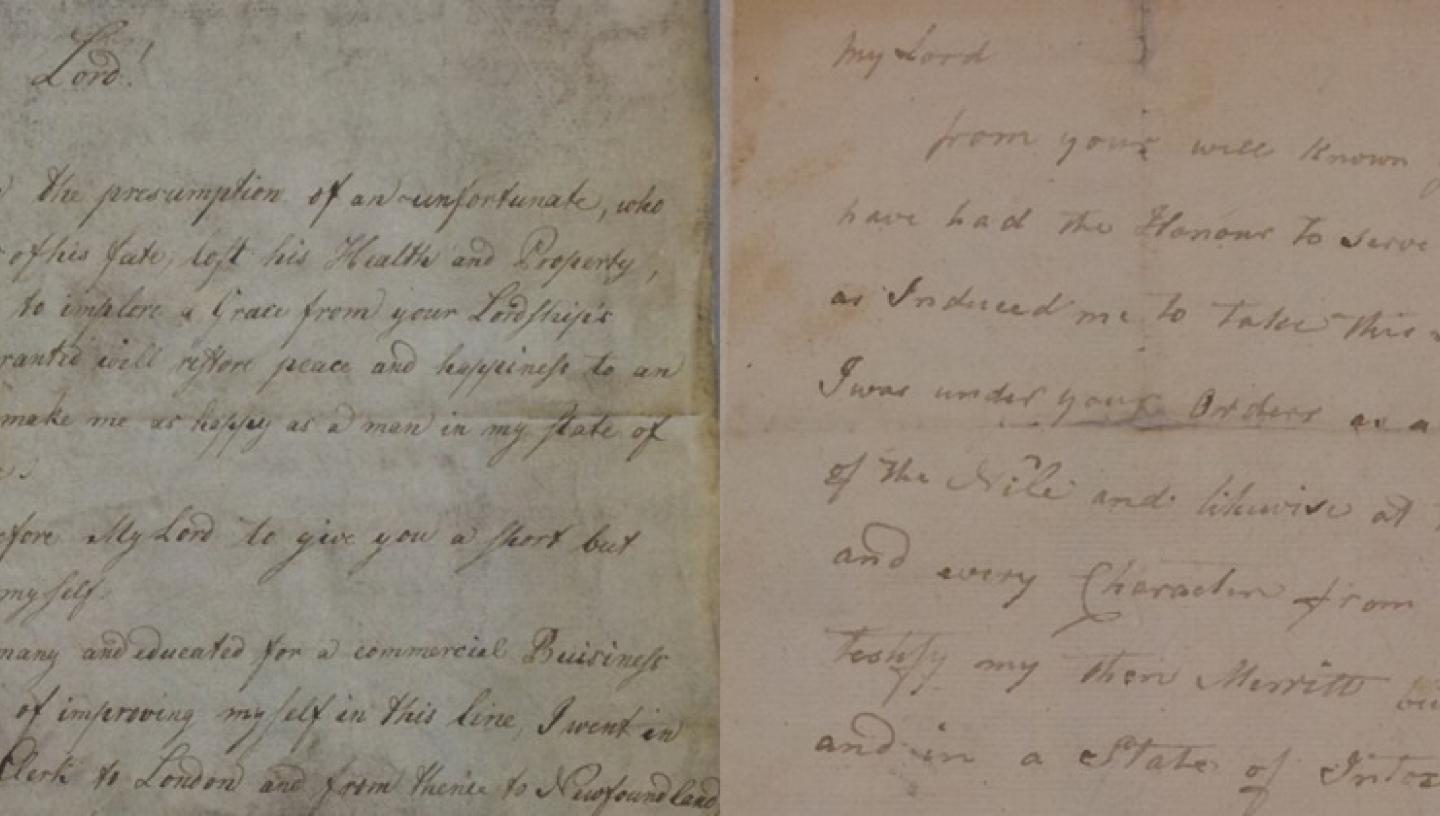

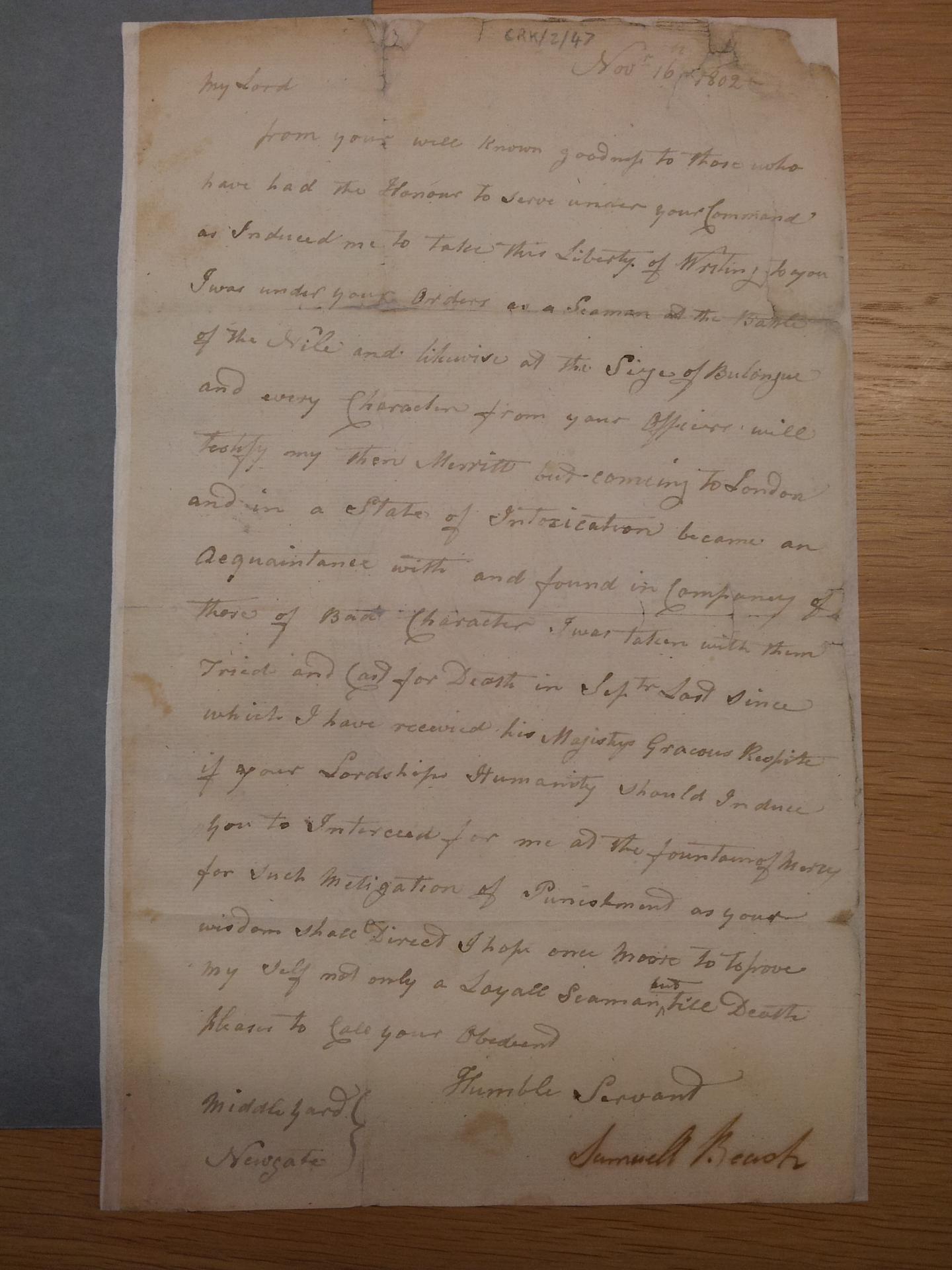

Samuel Beech wrote from Newgate Gaol on 2nd November 1802, claiming that after serving with Nelson at the battle of the Nile (1798), that:

"coming to London

and in a state of Intoxication [I] became an

acquaintance with [was] and found in Company of

those of Bad character I was taken with them

tried and cast for Death in Septr last"

Beech does not actually mention what crime he had committed to be ‘cast for death’. This was probably to focus attention on his present predicament and away from its cause. Though he had been spared the death penalty, Beech was anxiously waiting to hear exactly what form His Majesty’s pleasure might take, and appealed to Nelson’s apparently well known goodness to those who have had the honour to serve under your command for his influence in getting the sentence reduced.

Beech also did not say which ship he was on at the Nile. This is a strange omission for someone whose future depended on being able to convince Nelson that his case was genuine. Instead he wrote:

"I was under your orders as a Seaman at the Battle

of the Nile and likewise at the Siege of Bulongue

and every character from your Officers will

testify my then Merritt"

Yet research at the National Archives among the crew lists of all 15 British ships at the battle of the Nile, does not show a Samuel Beech among them. This is not conclusive evidence that he was not with Nelson, as it was not uncommon to give a false or ‘Purser’s name’, especially for impressed sailors. However, records for trials at Newgate in 1802 show that one Samuel Beech, a mariner from Dorset, age 27, was indeed convicted along with 8 others in September 1802, for Burglary in the house of George Skillecorre and stealing money. The record confirms Beach was sentenced to death but then pardoned and sentenced instead to ‘Transportation for Life’.

Why Beech was spared the death penalty is hard to say, but the records show that it was not uncommon to pardon a proportion of the convicted, presumably to underline His Majesty’s clemency. The last entry states Beech was delivered on board the Prudentia at Woolwich, February 1803. The Prudentia was a convict hulk. A surviving crew list records the arrival of several convicts from New Gate during November 1803, including Samuel Beech. This document also tells us what happened to him, recording that he was Pardoned 11 January 1806 to serve in the army.

It is tempting to think Nelson was not impressed by Beech’s inability to recall which ship he had been on and ignored his letter as a condemned man clutching at straws. Yet even if Nelson took no interest in his case, Beech’s naval service may have been enough to earn him his reprieve from the death penalty. Two and a half years later, Beech was 24 months into his sentence as a convict on the Prudentia when he was pardoned and sent to serve in the army. The date of this ruling was 11 January 1806, just two days after Nelson’s funeral. In this climate it is interesting to think that Beech’s previous association with Nelson (real or claimed), may have been enough to get his sentence of Transportation for life commuted to service in the army instead. It may of course have had no effect whatsoever and owed more to the army’s growing need for recruits!

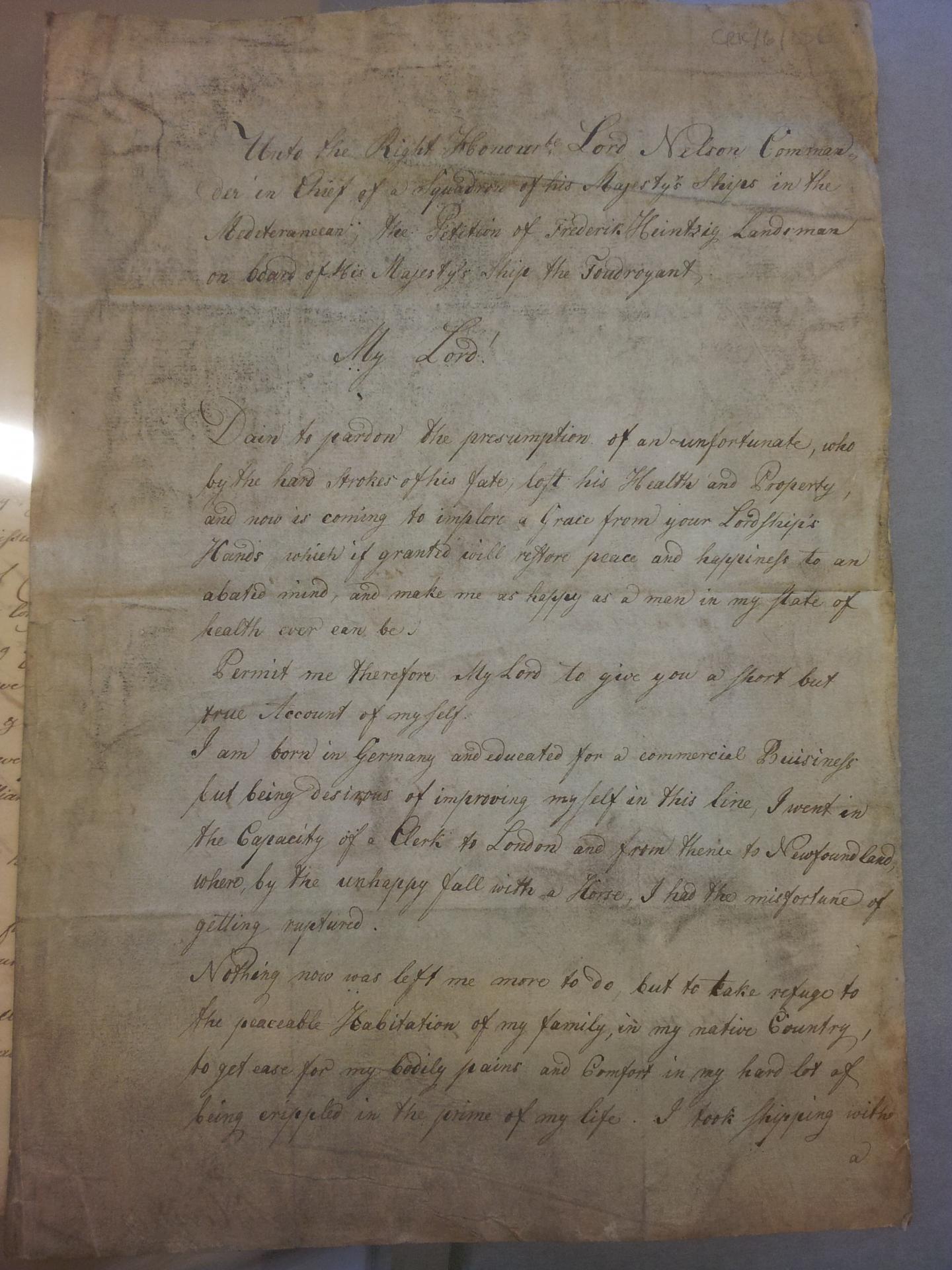

The second letter is from a German seaman named Frederik Heintzig, who was serving on Nelson’s flagship, the Foudroyant in July 1799, during the blockade of Naples. Heintzig claimed to have originally travelled to London and Newfoundland as a clerk, but been badly injured in a fall from a horse. Unable to work he took a passage home, was taken by a French Privateer and robbed before being put shore on the Portuguese coast, when he claims his

"appearance as a sailor was the occasion I was prest and with out being inspected or knowing myself where I was brought to, sent on Board of the brigg, the Speedy and soon afterwards on Board of this ship"

Like Beach, Heintzig also appealed to Nelson’s reputation for benevolence towards those who had served under him…

"Convinced of your Lordship’s feeling Heart, and that you

delight in rendering mankind happy, I lay down my humble

request to your feet to restore me to my family and myself

in discharging me from His Majesty’s service."

Heintzig’s claim of being a clerk is certainly supported by the fact he wrote his own letter to Nelson. The writing is fluent and well practised. Yet one wonders how badly he was crippled (which he claims curtailed his business career), if it left him fit enough to serve in the navy. Records also suggest Nelson was unmoved by Heintzig’s claim, as the Foudroyant’s muster roll continues to record his name six months later…

It is perhaps impossible to know if either Beach’s or Heintzig’s claims are true, but they are illustrative of range of subjects Nelson was petitioned about, the intricacies of fate which led some men to sea and today make for compelling snap shots of individual lives among the lower deck.

To find out more, visit the Caird Library & Archive

Martin Salmon, Archivist