22 Nov 2018

One of my recent cataloguing projects has been a collection of business records relating to Sir William Fraser, principal managing owner of several vessels in the service of the East India Company at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. The catalogued items all have the prefix FRS in the Archive Catalogue.

By Graham Thompson, Archives Assistant

Visit the Caird Library and Archive

Fraser’s interest in shipowning was a progression of the ambitions he had as an officer in the maritime service of the East India Company. His seagoing career began in 1759 and culminated in three voyages as commander of the Earl of Mansfield (1777) in the period 1777-1784. He gained some renown as a navigator, fixing the positions of locations in the China Sea using the lunar distance method of calculating longitude. He also acquired sufficient wealth through private trading to retire from the sea and invest in shipowning. This change was symbolized when Fraser became principal managing owner of the Neptune (1796), a new ship built as a replacement for the Earl of Mansfield.

Fraser’s business operated from premises at New City Chambers, Bishopsgate, London, in the period circa 1790-1815. The surviving archive material consists almost entirely of bundles of receipts, neatly arranged by ship and year. There are records of shares and dividends, insurance policies, and duties paid for charter parties and letters of marque, enabling us to form a picture of the administrative processes involved in managing merchant ships. In many cases this kind of ‘unremarkable’ material providing evidence of everyday transactions is discarded and lost from history.

Among the routine expenses were fees for pilotage; the purchase of provisions, stores and equipment; payment of wages to crews; and charges incurred while vessels were berthed at East India Docks in London. A good number of expenses relate to the various trades involved in ship repairs and maintenance, with the regular jobs including the drying of bread rooms and magazines.

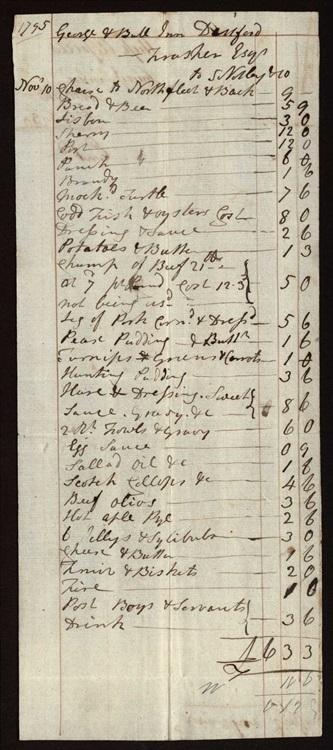

Among the most interesting receipts are those relating to survey dinners, presumably held to celebrate the launching, departure or financial success of ships. The image on the left is an example of a bill issued by Notley & Co at ‘The George & Bull Inn’ at Dartford, dated 10 November 1795 (Item ID: FRS/3/1/1). It comes from a bundle of receipts covering expenses of the ship Alfred (1790). The mouth-watering menu included mock turtle soup, cod and oysters, hunting pudding, dressed hare, beef olives, pease pudding, hot apple pie, jellies and syllabubs. The total comes to 6 pounds, 3 shillings and 3 pence. I found checking the bill to be a good exercise of my skills in working with pre-decimal currency.

The Alfred departed on her third voyage to China in March 1796. It was during this voyage that the Alfred and five other East Indiamen managed to disguise themselves as warships and bluff their way past a French squadron of six frigates in the Bali Strait without a shot being fired. Unfortunately, another ship managed by Fraser in this convoy, the Ocean (1788), was wrecked during a gale on the following day.

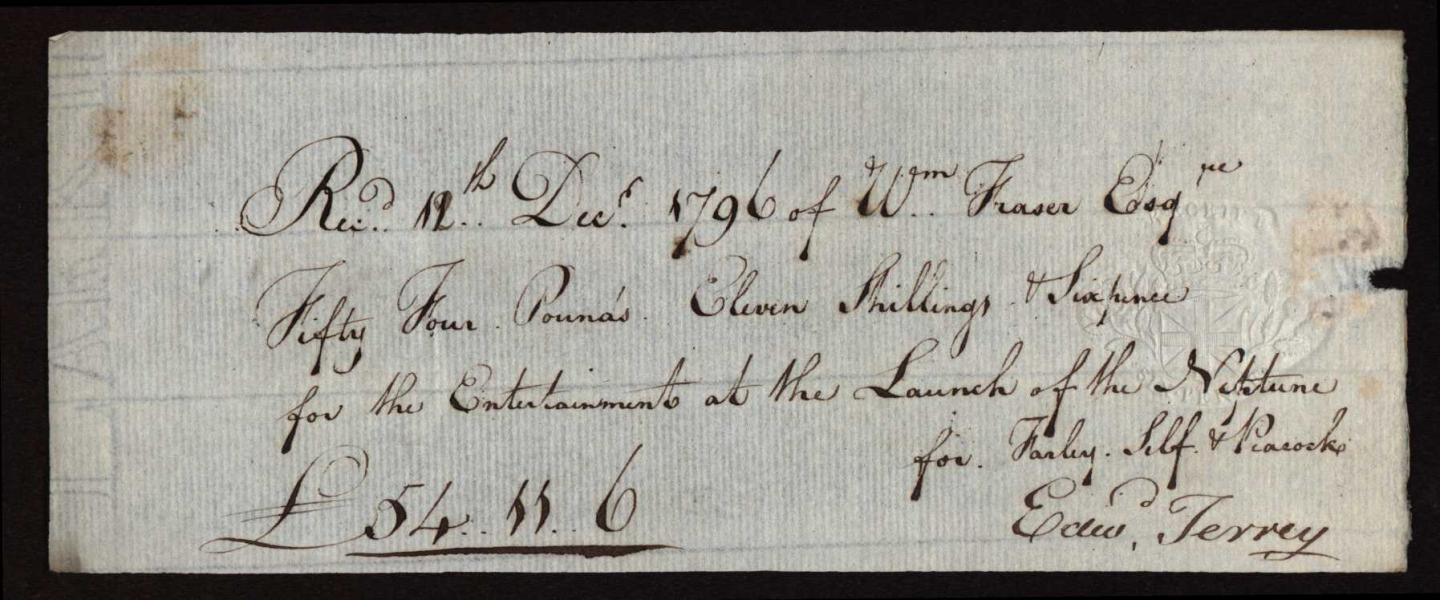

Another example of a survey dinner is that following the launch of the Neptune at Deptford in December 1796. This bill came to the much larger total of 54 pounds, 11 shillings and 6 pence, and was settled with Farley, Terry & Peacock, who appear to have been an upmarket catering company based at ‘The London Tavern’ in Bishopsgate.

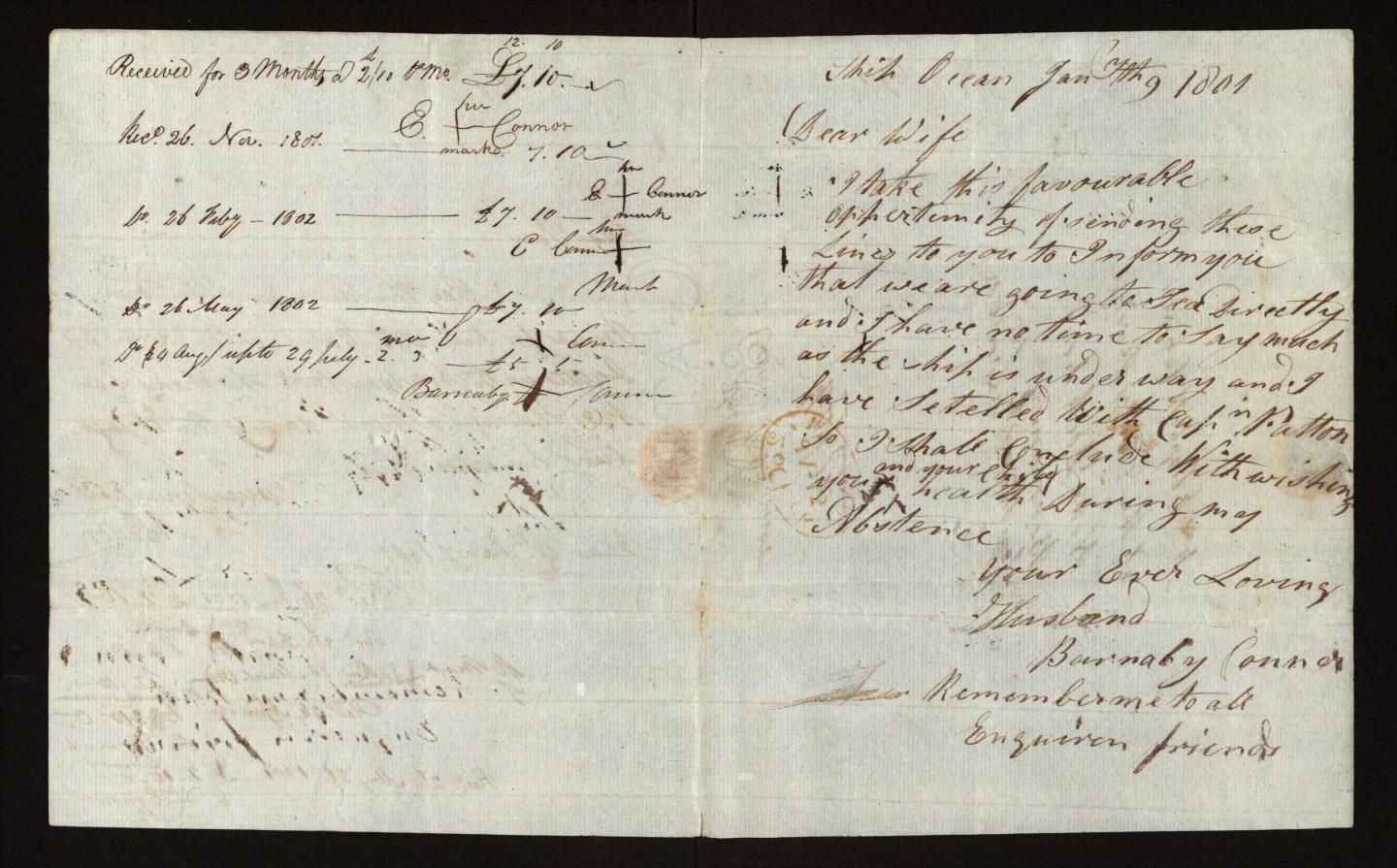

The lower end of the social scale is perhaps represented by records of the wages paid to wives or other nominated individuals while seamen were away from home. For example, there is a letter from Barnaby Conner, a sailmaker on the Ocean (1800), hurriedly written as the ship was getting underway from Portsmouth in January 1801. Conner only has time to quickly confirm that he has settled with Captain Patton and convey best wishes to his wife and child living in Bermondsey. The rest of the sheet has a record of the 5 pounds from extra wages ‘in the river’ and then 50 shillings per month received by Elizabeth Conner until the end of July in the following year when her husband returned home.

This collection doesn’t tell us much about Fraser himself and we are left wondering whether there is any underlying controversy or other narrative. We do know that Fraser’s finances were enhanced through his marriage in 1786 to Elizabeth (Betty) Farquharson, a daughter of the London merchant and shipowner James Farquharson (1728-1795). Fraser had a joint account with his father-in-law and later became one of his executors, as shown in the bundles labelled ‘exors. receipts’ from the period 1795-1805, see FRS/2. Fraser’s associates included Moses Agar (1770-1858), a shipowner, merchant and underwriter who became bankrupt in 1807.

We also know that Fraser fathered a multitude of children. Newspaper obituaries made sensational claims about twenty-eight offspring, with seventeen surviving at the time of his death in 1818. However, published details of the Fraser family peerage and a memorial tablet erected in St. Marylebone Parish Church in London, both state that he left a widow, three sons and eleven daughters. Lady Fraser died in 1834 and was buried at Langton Long in Dorset, where the Farquharson family had a country estate.