Becoming Queen Elizabeth I

Various dramatic events led to Elizabeth I taking over the throne from the Catholic Queen Mary I.

Edward VI of England died at the age of 15 in 1553. Earlier in the year, he had overturned his father's will, disinherited his sisters and named his Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey as his successor.

The heart of Edward’s problem was that Mary, who had been next in line to the throne, was a Catholic, and the established religion was Protestantism. Following his Protestant beliefs, Edward had also believed that women were not fit to rule. Instead he declared they could serve as regent for their sons until they reached the age of 18. Neither Mary nor Elizabeth had children.

The rise of Mary I

Because all the candidates for succession were female and without children, King Edward VI named Lady Jane Grey and her male heirs as his successors. Nine days after Jane’s accession Edward's plan was foiled. Mary gathered enough support to ride to London, laid claim to the throne and had Jane executed.

The return of Catholicism

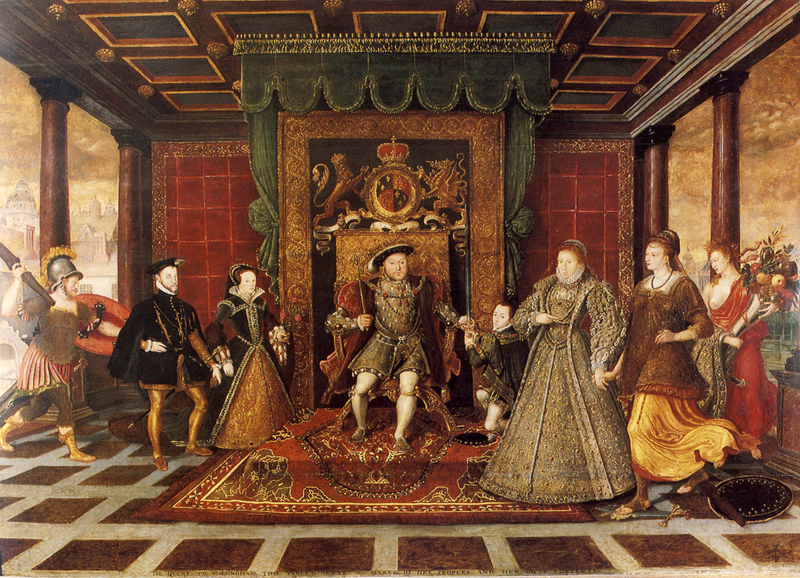

Henry VIII's Reformation had made the monarch the spiritual as well as secular head of the realm, with Protestantism coming in under Edward VI. Mary reversed all of this when she came to power in 1553. She restored Roman Catholicism as the state religion and the Pope as the head of the church.

Queen Mary always put principles first and enforced a campaign of harsh persecution for those who would not conform to Catholicism. During her reign some 300 people were burned at the stake and another 100 died in prison for being 'heretics', earning her the name of 'Bloody Mary'.

An unpopular queen

On top of rising resentment and fear about the religious changes Queen Mary had brought in, public hostility was also growing towards her intended marriage to Prince Philip of Spain, soon to become King Philip II. There were deep divisions in her council over the matter as members had no desire for England to become a subordinate of Spain. Queen Mary finally got her council to agree to the marriage but had not counted on the strength of public feeling against it.

Wyatt's revolt

Opposition to Mary's forthcoming marriage culminated in Sir Thomas Wyatt's revolt (1554). Wyatt's aim was to depose Queen Mary, marry Elizabeth to Edward Courtenay, an English descendant of the House of York, and place them both on the throne. The uprising was crushed, Wyatt was executed and for the second time in her life, Elizabeth was suspected of treason.

Mary and Elizabeth were not close. The half-sisters were separated by age and religion, and Mary had always resented Elizabeth as the daughter of the woman who replaced her mother as queen. As Mary's Protestant heir, Elizabeth was the natural focus for those discontented with Mary. It took little convincing for Mary to believe Elizabeth was involved in the plots against her.

The threat of execution

Although there was little evidence linking Elizabeth with the Wyatt revolt, Mary believed that she was involved and hoped that Elizabeth would confess under interrogation.

Elizabeth wrote to her half-sister pleading for an audience with her, while two of Mary's councillors waited to escort her by barge from Whitehall Palace to the Tower. She refuted the evidence against her and strongly proclaimed her innocence. With the threat of execution hanging over her, Elizabeth begged Mary not to condemn her unheard and reminded her 'that a king's word was more than another man's oath'. She drew diagonal lines at the end of her letter to prevent anyone inserting forged material and added a postscript: 'I humbly crave but one word of answer from yourself.'

Protesting her innocence

Mary was not moved by Elizabeth’s letter and refused to see her sister. Elizabeth was taken to the Tower the next day and imprisoned for two months. During this time Elizabeth did not crack under interrogation and continued to protest her innocence. Without enough evidence to put her on trial, she was eventually released and placed under house arrest at Woodstock, Oxfordshire.

The death of Mary I

Mary's popularity continued to plummet as the persecution of Protestants carried on and England became a pawn in Spain's war with France. This led in 1557 to the loss of Calais, England's last remaining French possession, and its only remaining overseas territory.

Mary desperately wanted a child to secure England's future as a Catholic nation but, after a number of false pregnancies, realised she would die childless. Without ever mentioning Elizabeth by name, Mary reluctantly consented to the next successor according to the terms of Henry VIII's will. Mary died on 17 November 1558 and Elizabeth became Queen.