Angry girls, giraffes, rhinos and men with shining armpits. The stars seen through the eyes of traditional South African societies.

Every culture on Earth has looked up to the stars for practical information and answers to the biggest of questions. More often than not what is learned is wrapped up in stories and passed down the generations.

Orion and the Pleiades

IsiLimela or the Pleiades were the 'digging stars', whose appearance in southern Africa warned of the coming need to begin hoeing the ground. All over Africa, these stars were used as a marker of the growing season. 'And we say IsiLimela is renewed, and the year is renewed, and so we begin to dig'. (Callaway 1970). Xhosa men counted their years of manhood from the time in June when IsiLimela first became visible. According to the Namaquas, the Pleiades were the daughters of the sky god. When their husband (Aldeberan) shot his arrow (Orion's sword) at three zebras (Orion's belt), it fell short. He dared not return home because he had killed no game, and he dared not retrieve his arrow because of the fierce lion (Betelgeuse) which sat watching the zebras. There he sits still, shivering in the cold night and suffering thirst and hunger.

A girl child of the old people had magical powers so strong that when she looked at a group of fierce lions, they were immediately turned to stars. The largest are now in Orion's belt.

For the Tswana, the stars of Orion's sword were 'dintsa le Dikolobe', three dogs chasing the three pigs of Orion's belt. Warthogs have their litters while Orion is prominent in the sky – frequently litters of three.

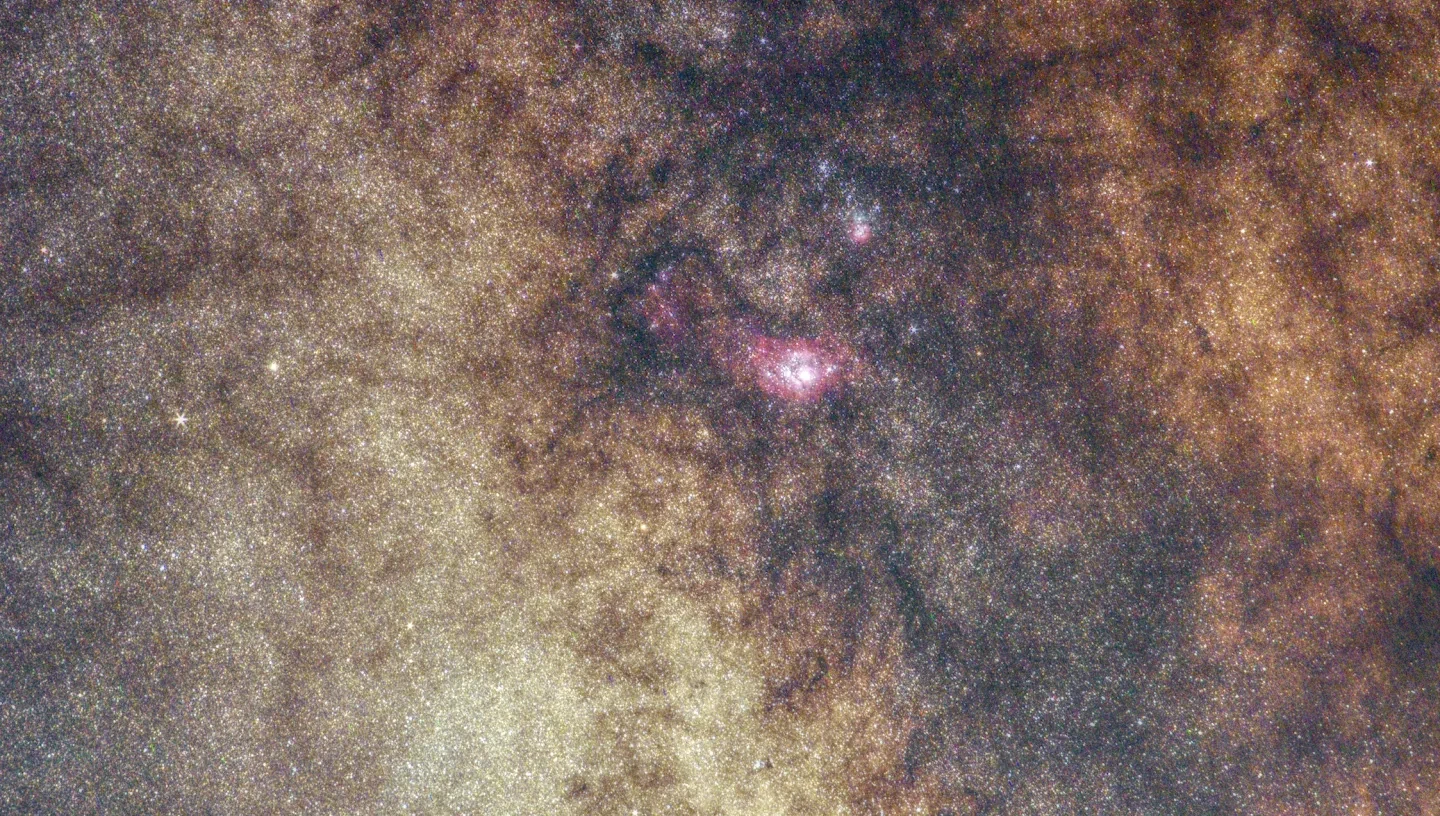

The Milky Way

A strong-willed girl became so angry when her mother would not give her any of a delicious roasted root that she grabbed the roasting roots from the fire and threw the roots and ashes into the sky, where the red and white roots now glow as red and white stars, and the ashes are the Milky Way. Dornan, 1925 (The Bushmen)

And there the road is to this day. Some people call it the Milky Way; some call it the Stars' Road, but no matter what you call it, it is the path made by a young girl many, many years ago, who threw the bright sparks of her fire high up into the sky to make a road in the darkness. Leslau, Charlotte and Wolf. African Folk Tales (1963)

To Xhosas, the Milky Way seemed like the raised bristles on the back of an angry dog. Sotho and Tswana saw it as Molalatladi, the place where lightning rests. It also kept the sky from collapsing, and showed the movement of time. Some said it turned the Sun to the east.

The Stars

A legend of the Karanga people held that the stars were the eyes of the dead, while many Tswana believed that they were the spirits of those unwilling to be born. Other Tswana believed that they were the souls of those so long dead that they were no longer ancestor spirits. The Venda pictured the stars as hanging from the solid dome of the sky by cords, while other groups believed the stars to be holes in the solid rock dome of the sky.

The Moon

Its markings are a woman carrying a child, who was caught gathering wood when she should have been at a sacred festival. (Tswana)

Many Africans saw the markings on the Moon as a man or woman carrying a bundle of sticks.

'In Malawi the morning star is Chechichani, a poor housekeeper who allows her husband the Moon to go hungry and starve; Puikani, the evening star, is a fine wife who feeds the Moon thus bringing him back to life.'

For the Khoikhoi, the Moon was the 'Lord of Light and Life'.

Among the Xhosa it was believed that 'the world ended with the sea, which concealed a vast pit filled with new moons ready for use', i.e. that each new lunation begins with a truly new moon.

Nwedzana = waxing crescent. If the horns point up when the new crescent is sighted in the evening sky, it 'was said to be holding up all kinds of disease, and when the horns were tipped down, the Moon was a basin pouring illness over the world.' (Sotho, Tswana, Venda)

In Bushman legend, the Moon is a man who has angered the Sun. Every month the Moon reaches round prosperity, but the Sun's knife then cuts away pieces until finally only a tiny piece is left, which the Moon pleads should be left for his children. It is from this piece that the Moon gradually grows again to become full.

The Sun

The Sun was once a man who made it day when he raised his arms, for a powerful light shone from his armpits. But as he grew old and slept too long, the people grew cold. Children crept up on him, and threw him into the sky, where he became round and has stayed warm and bright ever since. (Khoikhoi and San)

Some believed that after sunset the Sun travelled back to the east over the top of the sky, and that the stars are small holes to let the light through. Others said that the Sun is eaten each night by a crocodile and that it emerges from the crocodile each morning.

According to a Naron bushman, the Sun turned into a rhinoceros at sunset, which was killed and eaten by the people in the west. They then throw the shoulder blade towards the east, where it turns into an animal again and starts to rise.

One Zulu tradition held that the Sun died at sunset each day, and was eaten by a race of pygmies called iZichwe.

Canopus and the Southern Cross

Canopus was known to some tribes as the 'ants' egg star' because of its prominence during the season when the eggs were abundant. The bright stars of the pointers and the southern cross were often seen as giraffes, though different tribes had different ideas about which were male and which were female. Among the Venda the giraffes were known as Thutlwa, 'rising above the trees', and in October the giraffes would indeed skim above the trees on the evening horizon, reminding people to finish planting.

According to Credo Mutwa, the Southern Cross is the Tree of Life, 'our holiest constellation'.