How do we see and hear the Universe? It's a simple question with a complicated answer.

So much of the data that modern telescopes and space missions capture is invisible, inaudible and imperceptible. How can humans process that information? How do we turn it into something we can see, hear and understand?

That is the challenge set by the Annie Maunder Prize for Image Innovation, part of the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition. The category encourages people to take existing astronomical data and transform it into a work of art.

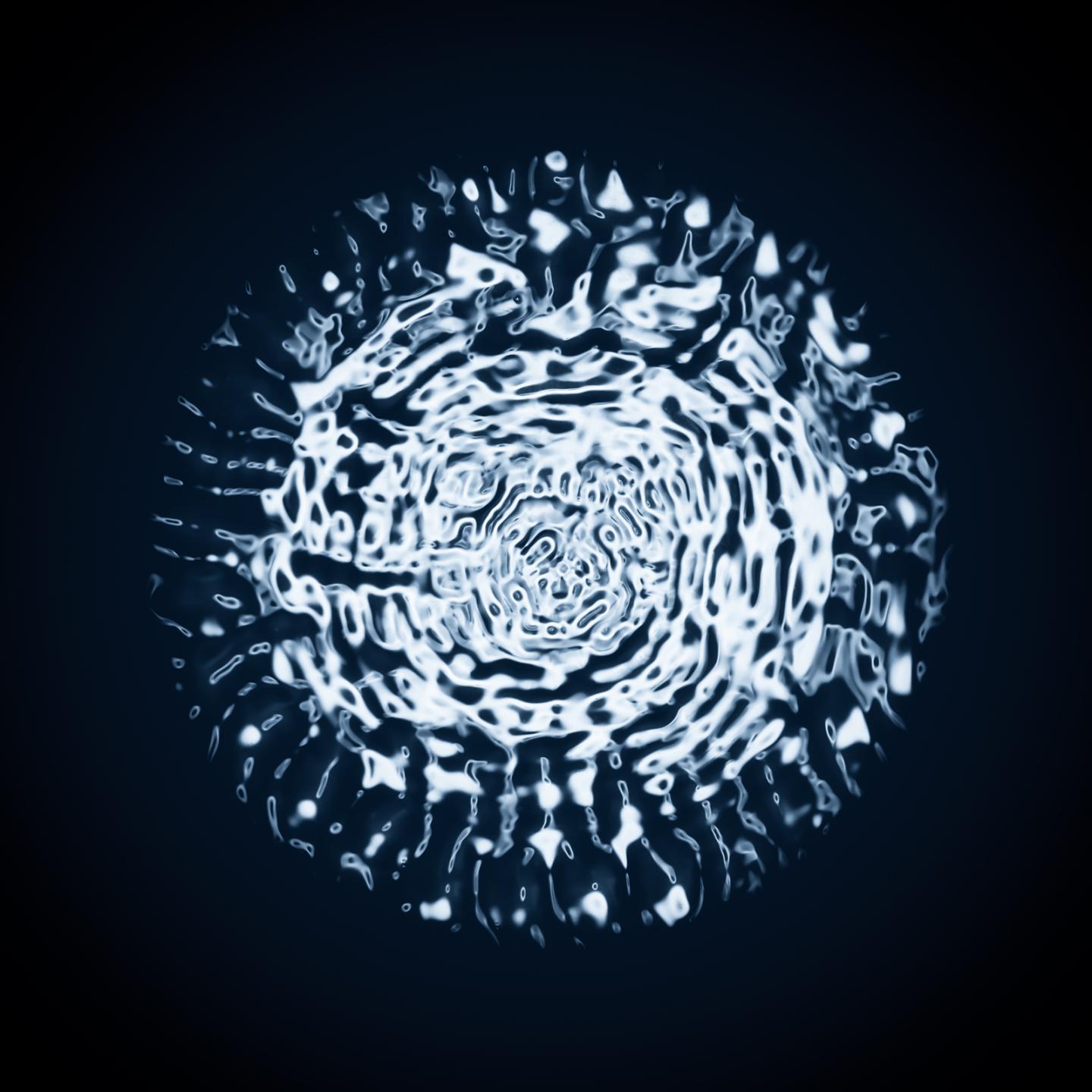

Astrophotographer John White won the category in 2023. His image Black Echo shows a complex pattern of water droplets, vibrating to the 'sound' of a black hole.

Royal Observatory Greenwich astronomer Ed Bloomer says, "This is an image of a sound caused by a source that is invisible. Stark, beautiful, rather weird, and certainly innovative!”

Watch the video to see how Black Echo was created, and read on to discover more about John's fascinating work.

What encouraged you to create this image?

I'd been tracking the Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition for a while and I really wanted to try and push the boundaries of what processing something sourced from the Universe meant.

A lot of my previous stuff had involved finding an image, putting it in Photoshop and doing something cool with it. Photographic processing however used to be much more of a physical process than a digital one, so I started to think more broadly about what I could do.

NASA had released these mind-boggling audio clips of the 'sound' of a black hole as it transitioned through some of the gas in the Perseus galaxy cluster. It set my mind running: how could I visualise this audio? How could I process this signal through a physical medium and create something new?

Fast forward after lots of Googling and I'd uncovered this topic called 'cymatics', which is all about the physical representation of sound. Then it was time for experimentation.

How did you create Black Echo?

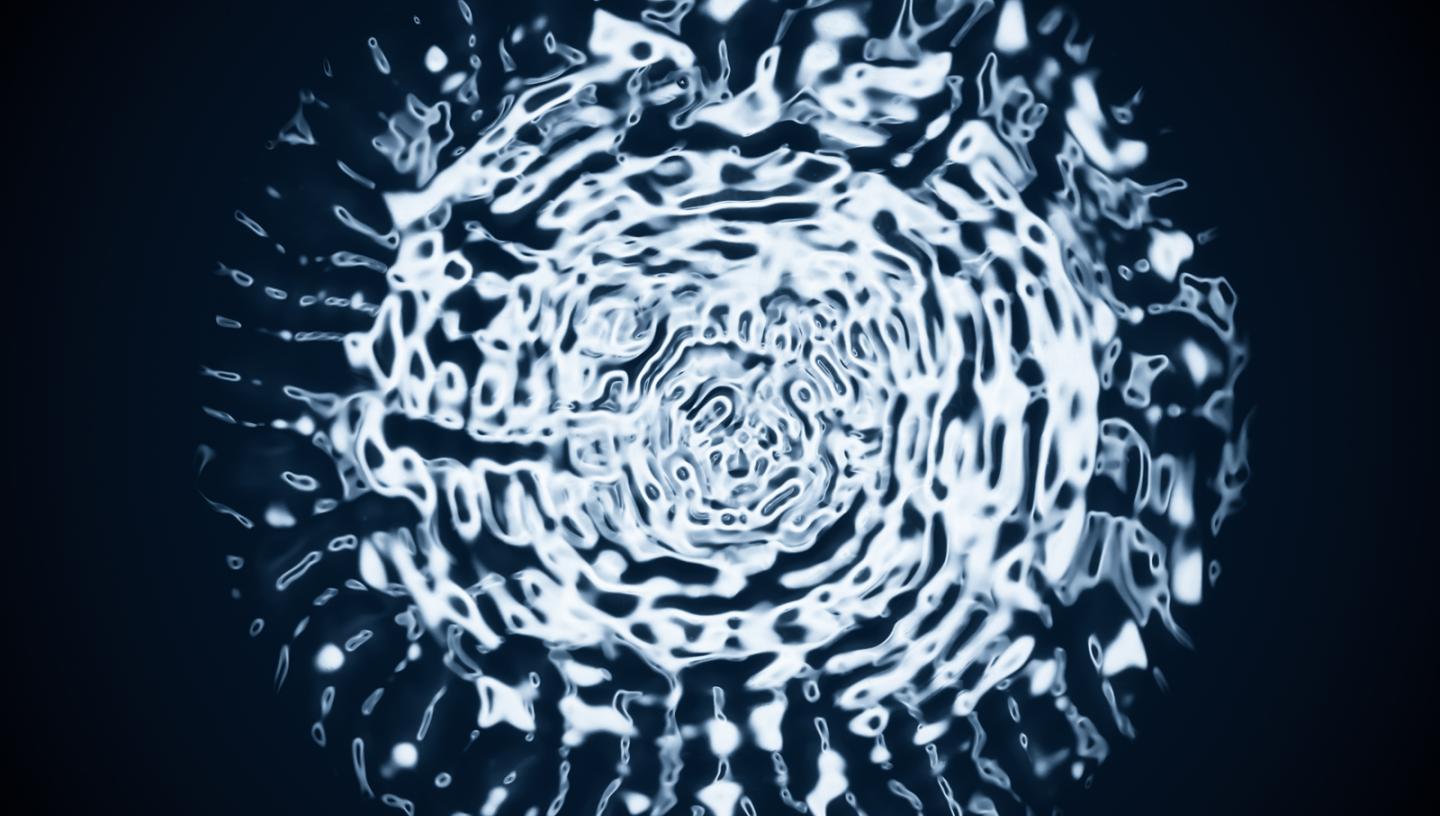

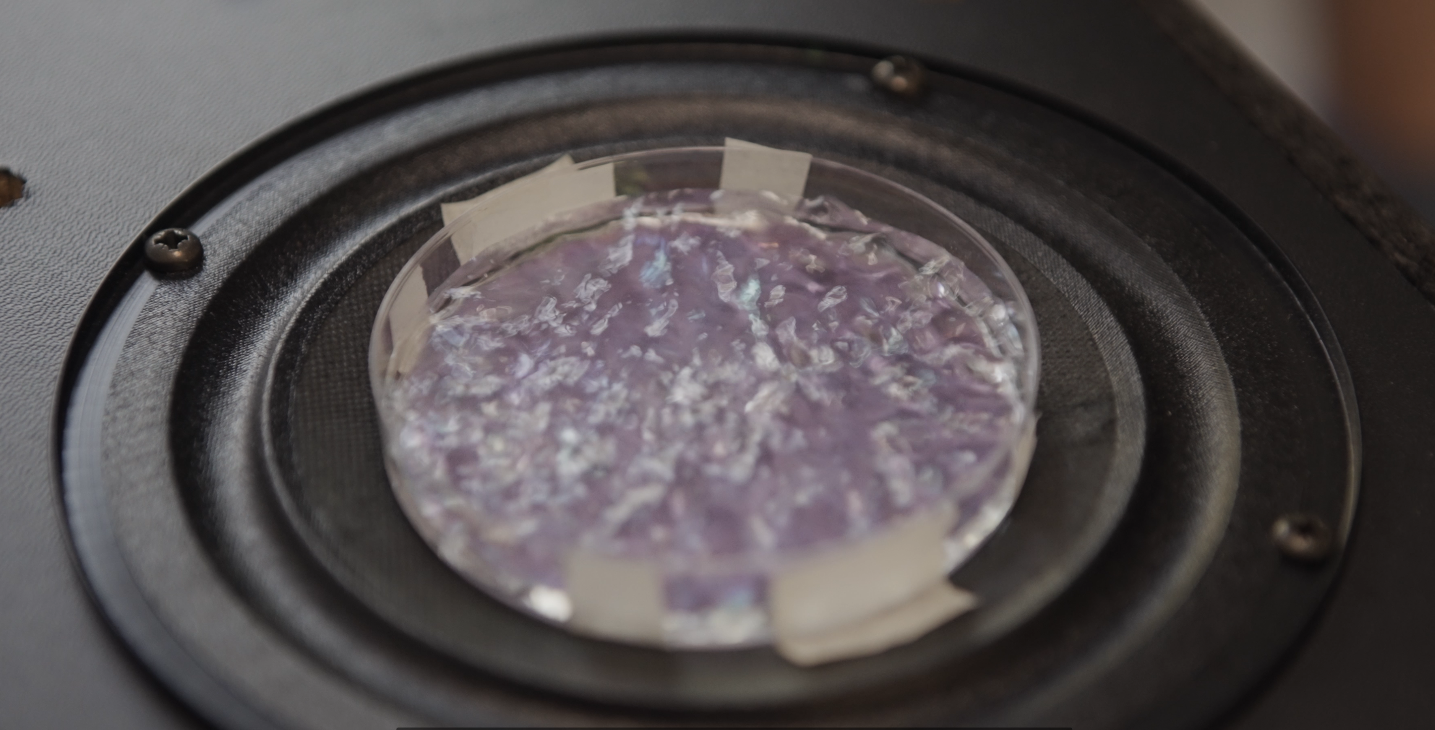

I passed the audio of the black hole through a receiver into an old speaker, onto which I had attached a petri dish, blacked out at the bottom and filled with about three millimetres of water.

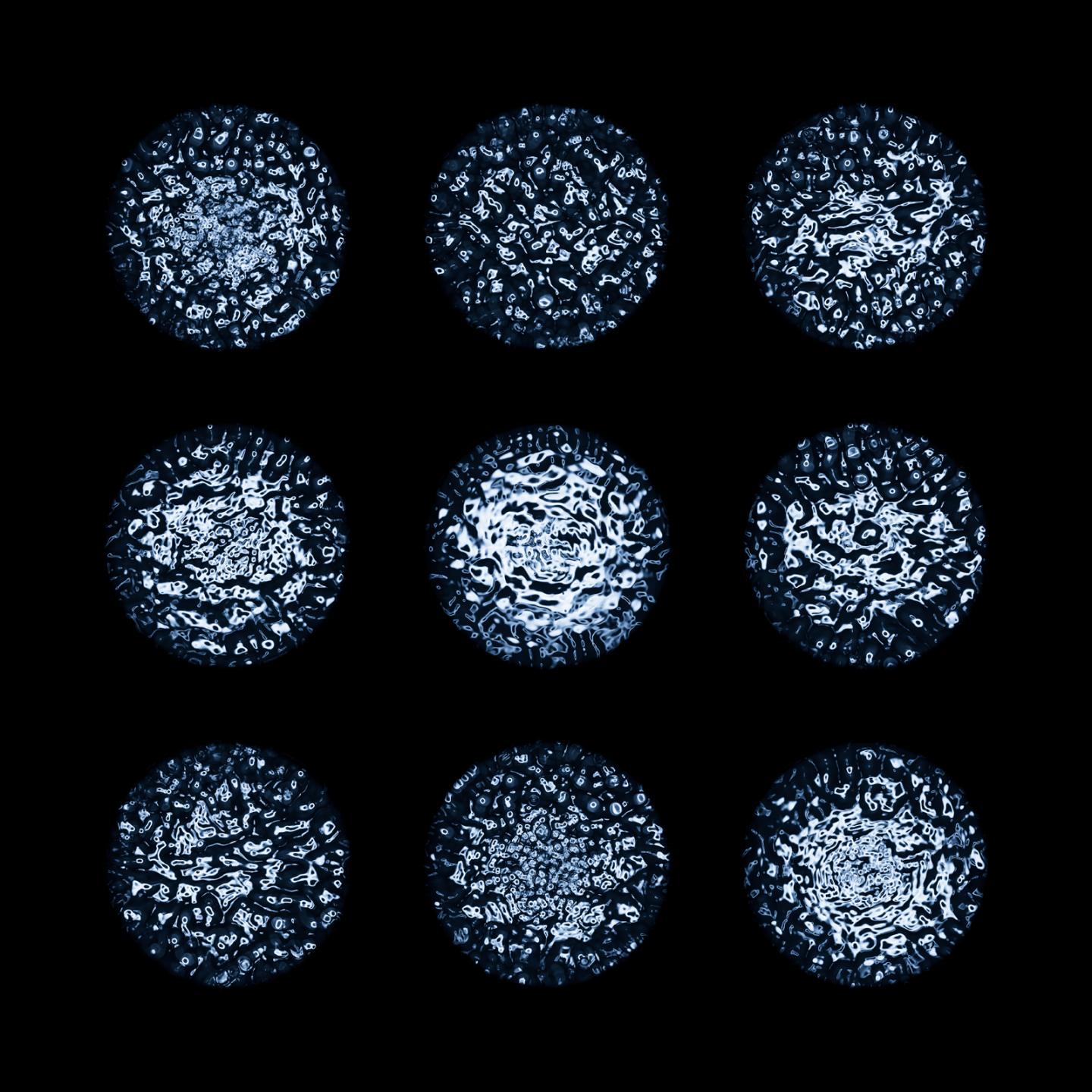

Shooting directly down with a macro lens and halo light in a dark room, I took probably 100 shots, experimenting with the differences in the audio and volumes to explore the various patterns made in the liquid.

Water in this case is a perfect medium: as you change the frequency of the audio, the shape and the patterns of the vibrations change. That's why Black Echo is a unique representation of a black hole in my living room, because that shape 'came' from the black hole.

What I think is amazing about this project is seeing something millions of light years away suddenly existing in physical form in my living room. For a microsecond it's there, and then it's gone.

The project took six months to plan but just 10 minutes to execute; I didn't know if it would work until I had all the pieces assembled. That first moment I saw it on camera, captured those vibrations materialising in the water, was just pure joy.

I used an old speaker that I'd found for free online because I thought I was going to trash it with the experiment. Looking at the gear, I think apart from the camera the combined value of it all was about £3.50. For me it's a great example of how, with a bit of creativity and ingenuity, you can create something out of almost nothing.

Did anything else inspire your image?

This category is called the Annie Maunder Prize for Image Innovation. Annie Maunder was famous for making astrophotography more accessible by thinking about how it could be presented to a broader audience.

For me, the goal of this experiment was to try and channel some of that creativity and to do something different, because she did things differently in a time where it was incredibly hard for a woman to do anything in this sphere.

As a father of two daughters I talked to them a lot about Annie because she's a really inspirational character. So that was the genesis of this project: not to do a better version of something that already exists, but to do something that hadn't been done before.

That required reassembling the art of the possible, pushing the boundaries and integrating new techniques. You never know if these things are going to work when you start but, you know, that's the fun of it!

What advice would you give to someone wanting to create astronomy art?

The creative process is not trial and error, it's just trial and reveal. If you don't try you can guarantee that you'll get nothing – the process of experimentation is often the path to new ideas. It reveals things.

If you're squirting ink into oil or oil into milk – which I've done! – you never know what it's going to look like until you try.

So I would encourage anybody in this space to try and experiment and make a mess, because out of that mess comes something that hasn't been done before.

The world needs people to be bold and to do different things, because that's where you find the beautiful intersection of what can be done, what hasn't been done and what might be done in the future. And one day you could be the first person to do something, and that's a pretty cool feeling!

What interests you about space photography?

There's something really fascinating about the Universe, the endlessness of it. From a photography perspective it's a subject with infinite possibilities, and it's continually changing - you can look at the same sky 100 times and see a different thing.

When you're out there on your own at 3am in the middle of nowhere with nobody around, you just feel this sort of connection with life and the world around you that you just don't get day-to-day sitting in front of a computer. It's a space to find myself and a space to be calm.

And everything moves so slowly. You can sit for two hours waiting for things to line up in the right place, and there's nothing to do other than drink a cup of tea and gaze up at the stars. It's a really beautiful experience.

How did you get started?

I have always felt quite creative, but I'm largely rubbish at singing and drawing and things like that. So I picked up a camera around 10 years ago now, and realised that this was a really cool tool that allowed me to finally express my creativity.

I hadn't really realised at the time that I had selected one of the most technically challenging disciplines of photography to be the first thing that I wanted to learn, but I just dived head in. At the time I worked in London, so I probably spent 20 hours a week on a train watching YouTube tutorials and deciding what gear I needed.

And then, of course, like most genres of photography it's a rabbit hole that you can just go deeper and deeper into, and it's still something I really enjoy.

What advice would you give to someone looking to get into astrophotography?

I would say to anybody wanting to do this: do it, but don't expect perfection on day one. Creativity in photography is a lifetime pursuit and the journey is the reward.

You don't need expensive gear, you just need to start. Don't let technology be a barrier. Don't let anybody tell you that you can't do it because your camera isn't good enough.

The people that inspire me are not the people with expensive cameras; they're the people with great ideas. Anybody can have a great idea.

Find more stories from the exhibition