24 May 2019

The correspondence between mothers and wives to John Markham, on the Admiralty Board, reveals the surprising role these women played in attempting to secure their family's survival

by Conal Priest

The turn of the eighteenth century may appear an odd place for polite letters of women to be of much significance to the Royal Navy. Along with the eruption of revolutionary violence in France, the spectre of Napoleon cast a shadow over Europe. Yet, in the early 1800s, the correspondence between mothers and wives to John Markham, on the Admiralty Board, reveals the surprising role these women played in attempting to secure their family's survival.

Four women’s stories

These women understood their expected role in society and how they should express themselves. On a regular basis, they consulted popular letter writing guides. A common theme in the correspondence Markham received from concerned mothers and wives was a reminder of his connection to their family.

Mary Webster

Mary Webster, writing from No. 8 Prince’s Street, Plymouth Dock, on 23 March 1806, requested the endorsement of her son to Vice-Admiral Dacres. In order to ingratiate herself, Mary reminds Markham that her husband had been a carpenter aboard a ship Markham had once captained and in which he had taken a prize, HMS Hannibal. In fact, a letter sent four years later reveals her son did indeed enter the Royal Navy. Still, she is once again called upon to act as diplomat in the case of a late or lost certificate that prevents her son being confirmed aboard his new ship.

H. Carpenter

H. Carpenter, who wrote from aboard a Cutter in the Downs on 26 April 1804, saw fit to entreat Markham on her husband’s behalf. Mr Carpenter, aboard HMS Viper, confided in his wife that the ship was in a very poor state. The position of an early nineteenth century seaman was so precarious, however, that he decided not to inform his superiors of the problems. His wife relates that her husband fears the ship “might be paid off, which would be depriving him of the chance of having it in his power to provide for his family which, to him, is [a] serious consideration having nothing more than his pay.”

In his situation, where ruin seems on the horizon, it is left to Mrs Carpenter and her letters to intervene for the sake of her family.

Jemima Crozier

Jemima Crozier, writing from Kingsbridge on 6 June 1803, also saw fit to act where her husband could not. Jemima tells Markham that her husband, away in the West Indies, “knows nothing of the bustle” created by vacancies in the unnamed, though likely shore-side, department her husband wished to join. Taking his career in hand, she states that their eldest son remains “unprovided for” whilst his father is at sea. The marital conventions of the day prevented Jemima from exercising a great deal of financial independence. Hence, she is left “to resign myself to produce without acquiring and hope for the best”. Her situation appears dire and it is clear why she desires the position to go to her husband. He would stand to make more money, and relieve their situation. Like Mrs Webster, she calls on her husband’s relationship to Markham by reminding him of her husband’s service aboard Hannibal.

Elizabeth Dashwood

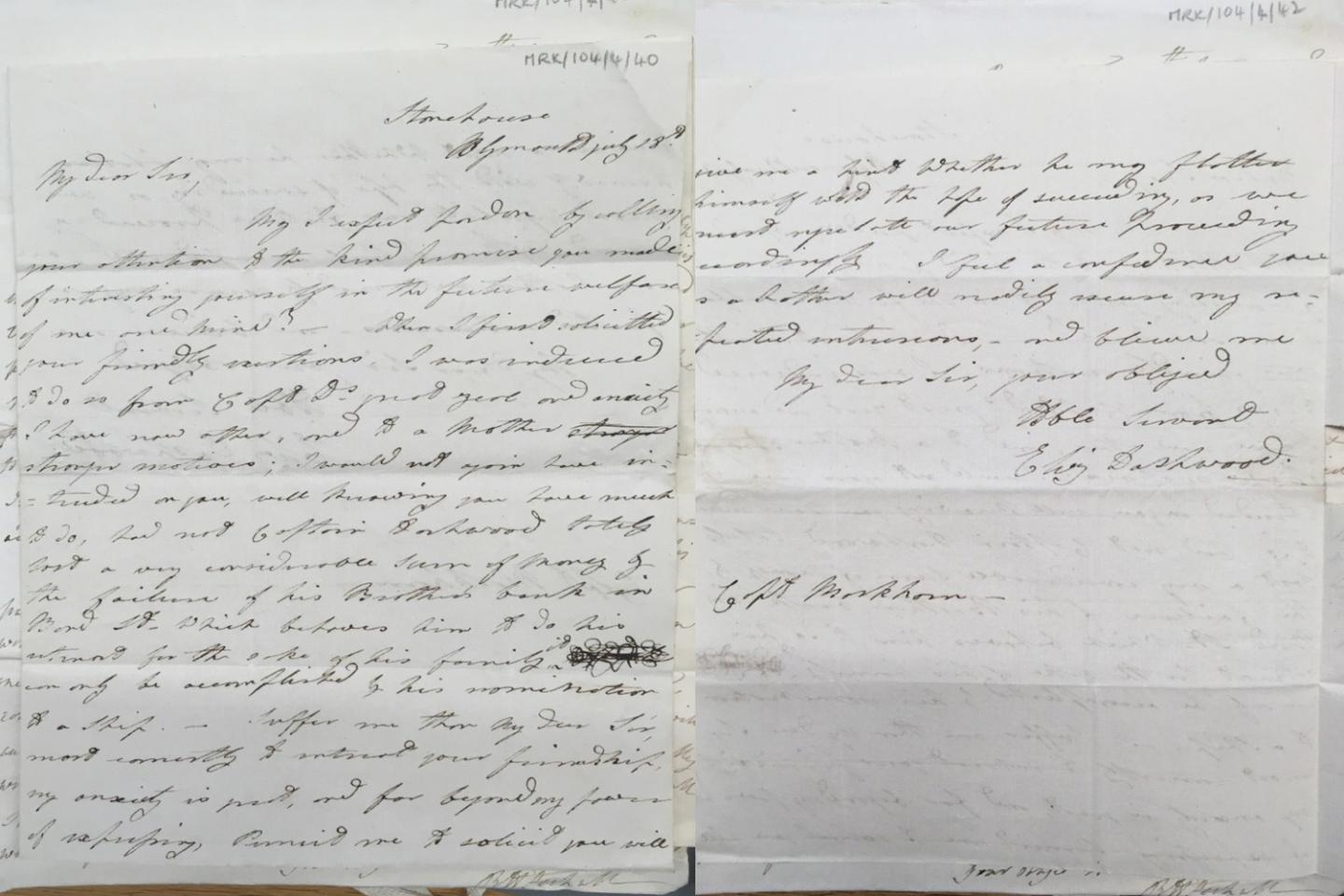

On 30 May 1803, Elizabeth Dashwood wrote to Markham from Plymouth, stating that she desired his help “to get my husband a ship”.

Her husband, Captain Dashwood, “from his anxious mind” and “fearing he may not have the good fortune to succeed” appears to have left his potential unfulfilled, and with it all that his family may have.

Having confirmed his abilities with his peers, Elizabeth took it upon herself to correct the situation, and strive for the betterment of her family. Indeed, she confesses that “Capt D is ignorant of my, perhaps, intruding letter”. A month later, pursuing the subject further, she writes again and goes so far as to name a specific ship, “La Poulette”. Elizabeth’s motives in taking such steps are betrayed, at least in part, in her statement that “it will be the means of serving us most essentially”, suggesting that material stability rather than mere careerism was at stake.

She sent another letter a month later, reminding Markham of “the kind promise you made of interesting yourself in the future welfare of me and mine?” This letter, so soon after the first, was precipitated by the hardship Elizabeth perceives for her family as “Captain Dashwood lately lost a very considerable sum of money by the failure of his Brother’s bank in Bond St which behoves him to do his utmost for the sake of his family.”

This is something Elizabeth clearly does not believe he is capable of alone. Elizabeth hopes the situation will be resolved by Markham finding a ship for her husband and ends the letter with a plea for the future of her family.

The conventions of letter writing

The art of letter writing was rooted in convention. These conventions sometimes obscure the truth and make genuine feeling difficult to distinguish from pretence. In the letters mentioned here, women establish their expected social subservience.

Rebecca Brett, when requesting a ship for her son stated: “I dare not presume to point out any, but if it could be to a frigate I should be the more oblig’d [obliged]”. In her later letter on the matter of the certificate, she begins to close with an apology “if I have presumed too far, on your goodness”.

H. Carpenter, conveying the delicate matter of the state of her husband’s ship, begins by stating that she “shall ever retain a most grateful sense of the very great favours with which you have honoured me”. She goes on to “beg leave to inform you”, placing herself within the subservient role.

Finally, Elizabeth Dashwood, in attempting to aid her husband, hopes Markham will “suffer” her “perhaps, intruding letter”. She remains subservient in her second letter when she states “I presume not to hesitate in most earnestly beseeching you”. In her final letter she begins with “May I expect pardon by calling attention to the kind promise you made” and ending with “I feel a confidence [that] you as a father will readily excuse my repeated intrusions”.

These women knew that the worth of their letters rested not only on their topic but on their form. They used their knowledge of writing conventions to ensure their endeavours were interpreted politely and respectfully. This contributed to the likelihood of their success.

Elizabeth’s letter to Markham from July 18th detailing the collapse of her brother-in-law’s bank on Bond Street. (MRK/104/4/40)

The hardships ashore

The lives of seamen during the early nineteenth century were extremely hard and they were frequently in mortal danger. But their wives and mothers ashore also faced hardships. The veil of convention and sociability that masked economic and social ruin was a thin one. All too often it threatened to fall away and reveal the hideous face of poverty and destitution. Despite this fear, these women showed remarkable tenacity by attempting to secure the social and financial future of their families, and keep the wolves from the door.