The wrecks of the HMS Erebus and Terror were discovered in 2014 and 2016, shedding new light on the fate of Sir John Franklin's final expedition.

But will we ever know the full story of what happened?

Explore the links to learn more about the lost Franklin expedition, and find out more about continuing work to recover the ships' secrets from the frozen depths.

HMS Terror was built in Topsham, Devon, and launched in June 1813. The ship was a bomb vessel, with an extremely strong hull, built to withstand the impact of explosions. Terror began its career as a ship of war, involved in several battles of the War of 1812 against the United States.

HMS Erebus was built by the Royal Navy in Pembroke Dockyard, Wales in 1826.

When its career as a bomb vessel came to an end, Terror became a ship of exploration. The ship ventured north to the Arctic in 1836, under command of George Back, where it suffered heavy ice damage in the aptly-named Frozen Strait.

The Erebus joined the Terror for the next expedition – to the opposite end of the Earth, the Antarctic – under the command of James Clark Ross (1839–43).

The ships were completely refitted with additional strengthening and an internal heating system. Together, they circumnavigated the continent and the expedition did much to map areas of Antarctica, the Ross Ice Shelf and set the scene for future polar exploration in that area.

The ships sailed into the Antarctic – which was just as perilous as the north – for three successive years in 1841, 1842 and 1843. In one incident, they were caught in a stormy sea full of fragments of rock-hard ice. The ice smashed against them so violently that their masts shook in a beating that would have destroyed any ordinary vessel.

Even more dangerously, in March 1842 the Erebus and Terror came close to destroying each other.

Erebus was suddenly forced to turn across Terror's pass in order to avoid crashing headlong into an iceberg which had just become visible through the snow. Terror couldn't clear both Erebus and the iceberg, so a collision was inevitable. The ships crashed violently together and their rigging became entangled. The impact floored the crew members while masts snapped and were torn away. The ships were locked in a destructive stranglehold at the foot of the iceberg until eventually Terror surged past the iceberg and Erebus broke free.

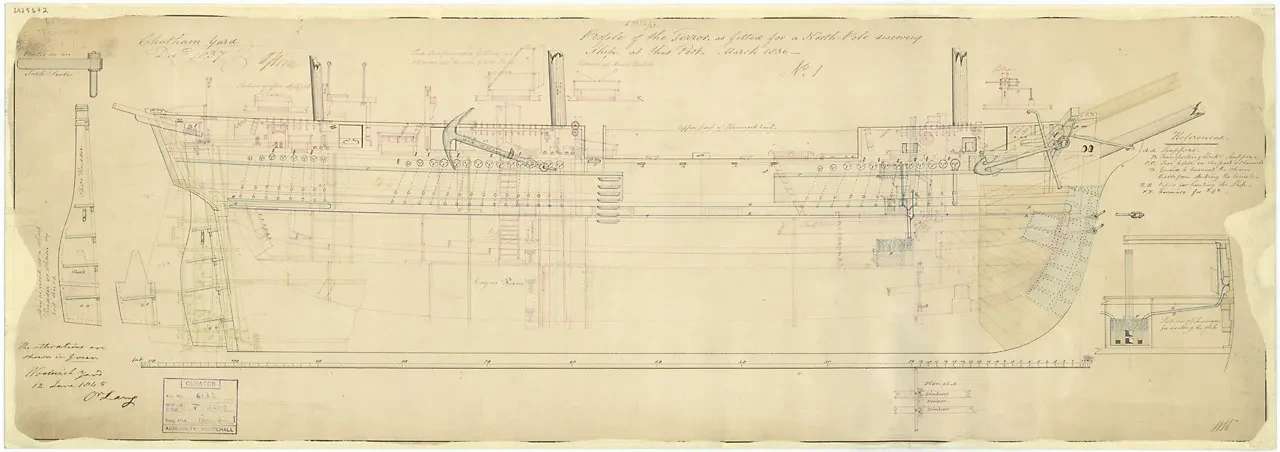

On its return with Erebus, Terror was again refitted and prepared for a voyage of scientific and geographical exploration through the North-West Passage under Sir John Franklin. In addition to being fitted similar to her 1839 voyage, both ships had additional planking on the upper deck and 20ft of iron sheeting along the sides from the bows. They also had steam engines and propellers added, which can be seen in green ink on the plan and required the stern to be rebuilt.

This was a brave decision, since the experiments with propellers were still underway within the Navy, and an engine with its need for coal would reduce the storage space for equipment and stores.

Finally the ships set sail for the North-West Passage in 1845 and were last seen by the whaler Enterprise on 28 July 1845 secured to an iceberg. The last definite information we have is that the Terror and Erebus were abandoned on 22 April 1848 from a message left by Captains Crozier and Fitzjames.

The Background information was provided by our curators, Claire Warrior and Jeremy Mitchell. Sir John Franklin’s Erebus and Terror Expedition: Lost and Found by Gillian Hutchinson informed the timeline of the ships’ discovery.

Main image courtesy of Parks Canada