Discover what to see in April's night sky including Leo the lion, Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks and the Lyrid meteor shower.

Top 3 things to see in the night sky in April 2024:

- Throughout the month - the constellation of Leo the lion

- 14 - 30 April - the Lyrid meteor shower

- 13 April - close approach of comet 12P/Pons-Brooks and Jupiter

Spotlight on Leo the lion

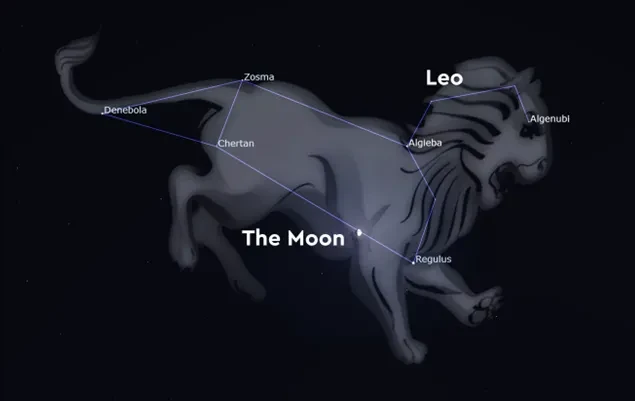

Leo is a spring constellation, high in the southern sky throughout the month. There’s something in Leo for everyone.

For those with very light polluted skies, two of the brightest stars, Regulus and Denebola, will be possible to spot. If you’re lucky and if you’ve let your eyes adjust to the darkness, you might also be able to make out the ‘sickle’ or backwards question mark shaped asterism which is the head of the lion.

You can also watch the Moon move through the constellation! The Moon’s orbital path across the night sky can be split into 27 equal segments, and it will spend approximately one day in each segment during its orbit of the Earth. These segments are known as lunar mansions, or lunar stations, and they are used for time keeping in many cultures, as well as having links to astrology. This April, the Moon will pass in front of Leo between the 17 and 19 of the month.

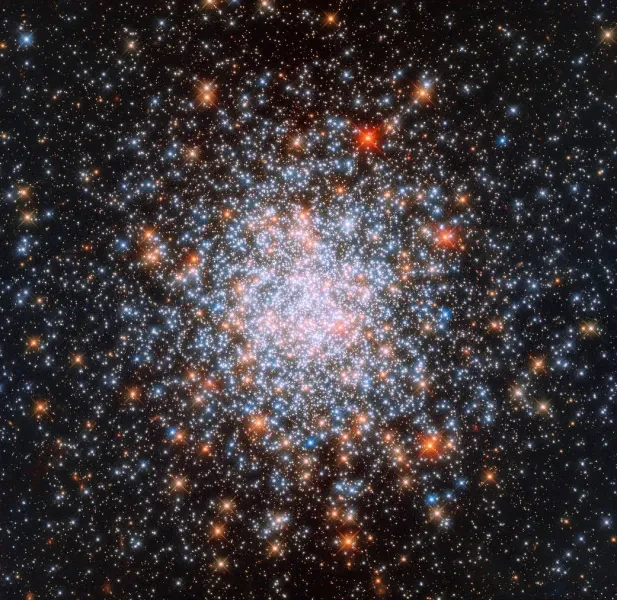

For those with dark skies, the full constellation including the fainter stars such as Zosma and Chertan can be seen. And then, if you have access to a telescope, you can find many distant galaxies in this area of the night sky. This includes the Leo Triplet, just below the star Chertan.

The Leo Triplet is a small collection of galaxies around 35 million light years away from us, including M65, M66 and NGC 3628. What’s interesting about these is that although they are all spiral galaxies, they are at different orientations, meaning they look very different in the sky. M65 and M66 are clearly spiral galaxies with the twisted arms of stars visible, whereas we see NGC 3628 ‘edge on’ and so its shape is less obvious. Another name for this galaxy is the hamburger galaxy. It's the galaxy on the left hand side of the image above if you want to judge how appropriate this name is for yourself.

Other deep sky objects in Leo include spiral galaxies Messier 95 and 96, and the elliptical galaxy Messier 105. There’s lots to explore in this part of the sky!

The Lyrid meteor shower

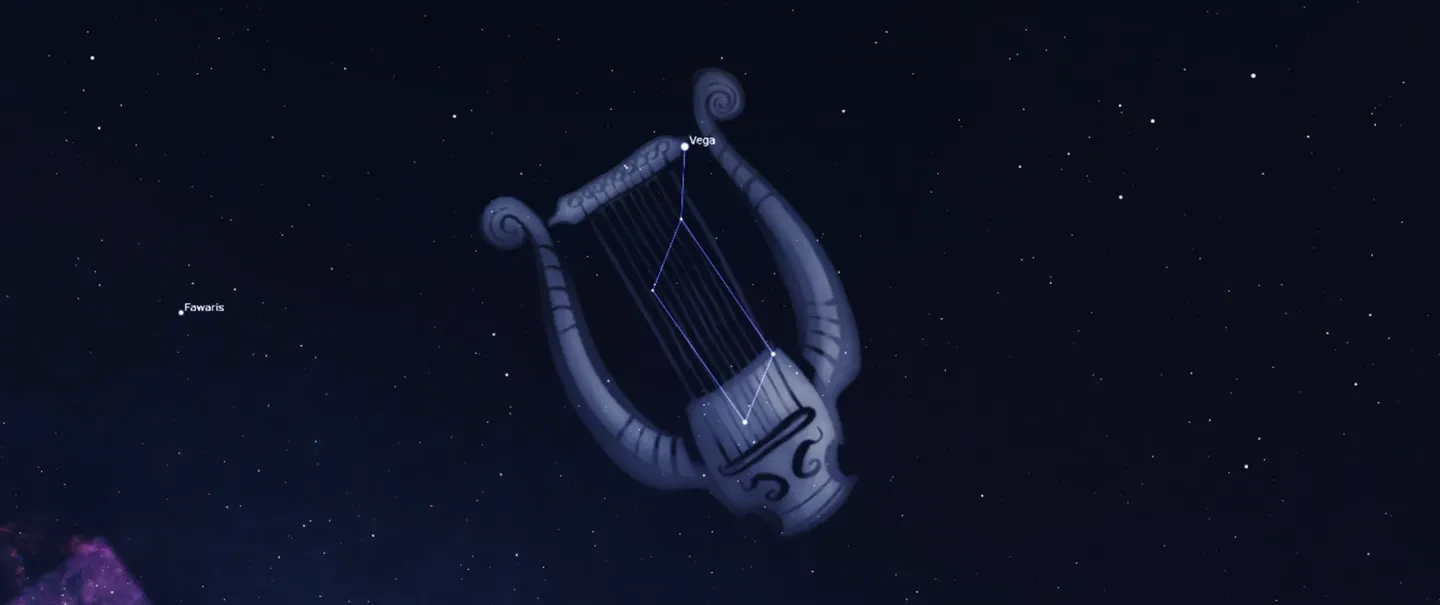

The Lyrid meteor shower will peak between 22 and 23 April, although meteors might be spotted across the whole second half of the month, between 14 and 30 April.

This meteor shower is not particularly active, with a predicted maximum of only 18 meteors per hour – compared to up to 100 per hour for the more prolific Perseids, for example. The conditions are also not that favourable this year, with the peak falling just before the full Moon. The bright light from a full Moon will make it harder to see meteors, and so it might be better to go shooting star spotting before or after the maximum, when the night is darker. The Lyrids are known for sometimes leaving persistent trains in the sky.

These meteors can be seen in any part of the sky, but if you traced their path back they would appear to originate from the constellation of Lyra, hence their name. However, their actual origin is Comet C/1861 G1, also known as Comet Thatcher. Comet Thatcher is named not after the British Prime Minister but after the amateur astronomer Alfred Thatcher, who discovered the comet in 1861. You won’t be able to see comet Thatcher for yourself as it’s a long period comet, only returning to the inner Solar System in about 250 years.

Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks

If you have access to a telescope or a pair of binoculars and you haven’t yet spotted Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, April will be your last chance to do so.

This comet will be increasing in magnitude throughout April, but also getting closer to the Sun, with perihelion (the closest approach to the Sun) occurring on 21 April. At this point, from our perspective the comet will be low to the horizon, close to the setting Sun in the early evening, making it more difficult to spot.

If you do want to find it for yourself, it will be in the western sky, starting in Aries at the beginning of the month, before a close approach with Jupiter on 13 April and then moving through Taurus. It’s predicted to be technically bright enough to be seen with the naked eye, at magnitude 5, but the light from the Sun in the early evening will mean that probably binoculars or a telescope is needed.

After disappearing from our evening skies the comet will swing past the Sun, with the closest approach to Earth happening on the 2 June, although at this point the comet will be in the daytime sky and not visible to us. After the comet passes by Earth it will head back to the outer Solar System, not returning to our skies for another 70 years.

North American Solar Eclipse

For parts of Canada, the United States, and Mexico, there will be a solar eclipse on 8 April. A total solar eclipse happens when the Moon passes in between the Sun and the Earth, totally blocking the face of the Sun and casting a shadow over one small part of our globe. These celestial events are relatively rare, and not only are they an exciting and awe-inspiring event to witness, but they are useful from a scientific perspective as well.

Normally the outer part of the Sun’s atmosphere, the corona, is difficult to see compared to the much brighter surface. However, during an eclipse this light is blocked, so the corona can be studied in much more detail, and scientists can use this time to collect data to help understand how energy is transferred from the Sun to the solar wind. The eclipse can also be used to study the Sun’s impact on our atmosphere. All this will happen on 8 April, from observations taken on the ground and using satellite data.

Something else that will make this event even more interesting is the presence of Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks in our skies. This comet will be above the horizon, but too dim to be seen with the Sun in the sky. Therefore, once the Moon is covering the Sun keen-eyed astronomers might also catch a glimpse of this comet during the eclipse!

For anyone not lucky enough to live in these specific areas, we will have to rely on photos and videos taken of the event. We won’t be experiencing a total solar eclipse in the UK until 2090, but there are partial eclipses and lunar eclipses for us to enjoy in the years upcoming instead.

Learn more about solar eclipses

Moon phases in April 2024

Last Quarter: 02 April (03:15)

New Moon: 08 April (18:21)

First Quarter: 15 April (19:13)

Full Moon: 23 April (23:49)

Stargazing tips

- When looking at faint objects such as stars, nebulae, the Milky Way and other galaxies it is important to allow your eyes to adapt to the dark so that you can achieve better night vision.

- Allow 15 minutes for your eyes to become sensitive in the dark and remember not to look at your mobile phone or any other bright device when stargazing.

- If you're using a star app on your phone, switch on the red night vision mode.

Header Image: Total Solar Eclipse, Venus and the Red Giant Betelgeuse © Sebastian Voltmer