Diaries written by English prisoners of war captured during the Napoleonic Wars frequently mention their clothing. Whilst the importance of appropriate clothing to the comfort and care of prisoners is obvious, prisoners frequently used clothing for their benefit in other, more creative, ways.

By Kelsey Power, King's College London

Visit the National Maritime Museum

Clothing frequently played a role in escape. Prisoners displayed a surprising amount of creativity in their attempts to smuggle tools and money, using the skills they’d learned adapting to ship-board life to their best advantage. The skills necessary to becoming a good sailor were of great use when it came to planning escape. Sewing, ropemaking, navigation, climbing and handling ropes, and creative problem solving could all come in handy. Buttons could be used to conceal gold coins, and rope to scale walls could be hidden under hats.

Prisoners would have had access to plenty of cloth. Despite its frequent use in escape attempts, actual clothing items remained scarce. Wealthy prisoners were able to provide for their own needs, and lower-class prisoners were often employed in making or altering the clothing issued to their fellows. John Tregerthen Short tells of a number of prisoners who even worked sewing French army uniforms. Unfortunately, no actual sample of the clothing issued to these prisoners of war is known to have survived. The brief descriptions given by prisoners in their diaries and published narratives are the only evidence that remains. Many of these accounts are held in the National Martime Museum in Greenwich at the Caird library.

Sewing

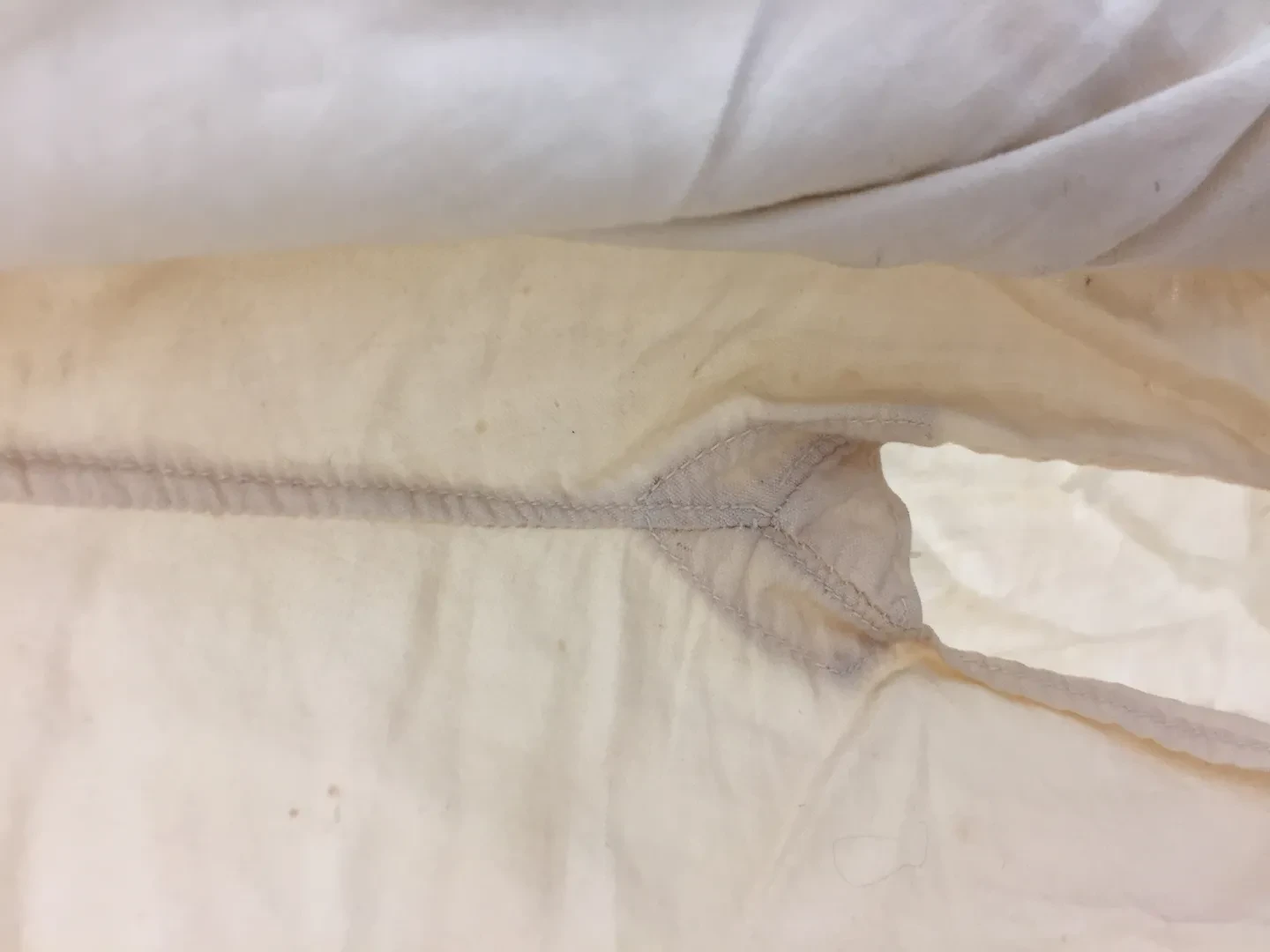

Sewing and mending skills are evident in the existing examples of seaman’s clothing. The uniforms in the collections at the National Maritime Museum provide a general guideline as to the principles of fit and function, and show that even in these higher quality examples, efforts were made to reuse and repair cloth and fittings.

While some of these repairs might have been carried out by professional seamstresses, or to modify the clothing for other wearers, the frequency of repair and the variety of materials, threads, and stitching techniques indicates that some were ad hoc repairs made by sailors with what they had on hand.

Multiple patches have been used to reinforce the weakest part in an officer’s coat.

This pair of breeches has been frequently mended, and it has at least five different kinds of buttons.

Buttons

Covered buttons were a frequent means of concealment, most often for cash. Coins could be sewn onto waistcoats or into the seams of shirts. Seacombe Ellison, captured after an escape attempt with three other prisoners, describes sewing five gold louis inside his flannel waistcoat, and one under the arm of his coat. A brief examination of the seam allowance generally given for these items shows that they would have needed to be altered to adequately conceal even the smallest coins. It is clear that disguising money as buttons was common. In recounting his re-capture, Ellison tells of how the guards immediately caught on to the trick:

One of them observed a button above the common size, and, thinking it looked suspicious, he cut into it, and out dropped a double louis,— which brought a grin upon all their countenances, and a few sacres from their tongues. All their knives were instantly in requisition, and the poor buttons were disemboweled in the most cruel and wanton manner: coat buttons, waistcoat buttons, pantaloon buttons,—all were ripped up; their hard hearts spared none, neither large nor small.

Ellison’s five gold louis survived the thorough search, which revealed a total of sixty louis hidden about his and his companion’s persons. Ellison’s experience proves that not only was choosing a unique hiding place important, but that having the sewing skills necessary to disguise the alterations made a huge difference to success.

Peter Gordon, formerly second mate of the merchant barque JOSEPH, planned an escape with two others from the depot in Cambrai. He was unusual in that he applied a systematic and academic approach to escape planning. He collected stories of failed and successful attempts, as well as looked to literary works like ‘The Life and Adventures of Baron Von Trenck’ for inspiration. After a few months of preparation, his friend, Copeland, was able to obtain a watch spring. Gordon describes his plan for the precious object:

I carried it to a watch maker, who I thought had the appearance of an honest man, to be made into a saw for cutting iron; he not only immediately consented to make it, but showed me a dozen or two of his own, which he said would answer better than the one I had, being stronger: but in this he was mistaken, as their strength would prevent their being coiled up, and covered like a button, which the other from its pliability admitted of, and in that shape, was intended to be secured to our clothes.

Unfortunately, Gordon’s extensive planning did not immediately pay off, as miscommunication about funds and timing nearly doomed his escape plan before he’d even made it out of the town. His ill luck continued throughout his journey through France, but after several misadventures he eventually made it to England.

Rope Making

Clothing was not always preserved, but instead torn or cut up to create ropes. Escape from France, a narrative written by an anonymous prisoner, explains how the author and his friends arranged to purchase cloth for the purported purpose of making shirts and trousers, and instead used the cloth to make rope. These ropes could be concealed, as done by Ellison and his group, by wrapping them around the body under the waistcoat. Thomas Williams, who was captured off the FRIENDSHIP in 1804, chose the alternate style, which was to conceal the rope under the crown of the hat. It is unclear how this might have been achieved with the French-issued straw hat, but examples of cocked hats show that there was often extra room in the crown. The hats included a lining that could be resized to fit the head using a draw string.

The case of Alexander Stewart is indicative of just how important the skills learned as a sailor could be to a successful escape. Stewart, a superstitious young man with very little experience at sea - he had been captured after only a few months on board, and he had nearly drowned from falling overboard twice - made his escape attempt from the citadel in Verdun. He and his co-conspirators spent six weeks collecting string and plaiting it into rope at night. During the day, Stewart kept the growing rope coiled under his hat, in constant fear that a gust of wind would blow it off his head. The night of their escape, Stewart was the first over the wall, but the rope was too thin to grip properly, and he’d wrapped it around his hand. He slid more than sixty feet to the ground and cut his hand to the bone. Stewart’s inexperience with rope-making and handling isn’t what doomed his escape, but it did nearly cost him his hand.

The use of seaman’s crafts like sewing and rope-making helped prisoners to shape their experience of incarceration and manipulate it to their own ends, they took skills learned or honed by their profession and prison experience and used them to get home. More information on this topic is available in the Caird Library, and examples of uniforms from this period are on display in the Nelson, Navy, Nation gallery.