We have all heard the saying ‘clothes maketh the man’. Perhaps it’s doubly true for women – especially those women who disguised themselves in order to run away to sea.

A delve into the Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum reveals numerous examples of women disguising themselves as men in order to live and work at sea.

Reading the records, you can’t help but wonder how they were able to disguise themselves for so long without being caught – especially when wounded. But these women didn’t just successfully disguise themselves; on revealing their true gender, some even received a pension for their services.

"Good People give attention & listen to my song,

I will unfold a circumstance that does to love belong.

Concerning of a pretty maid who venture'd we are told

Across the briny ocean as a Female Sailor bold."

- The Female Sailor

Female pirates

Two women have never been more famous for running to sea wearing men’s clothing than the pirates Anne Bonny (1698 – 1782) and Mary Read (1695 – 1721). These fascinating women were brought up as boys and found their way into piracy under the flag of Captain John Rackham.

Anne Bonny was born in Ireland in 1698 and had married a penniless sailor called James Bonny in 1718, much to her father’s disgust. Finding themselves turned out of home with nowhere to go, Anne and James headed to the Bahamas to find work. There Anne took up with the pardoned buccaneer Rackham, deserted her husband and went to sea. Soon pregnant, she gave birth to his child in Cuba. It did not take her long however to rejoin the crew dressed in men's clothing. Around the time of her first pregnancy Rackham’s crew had a new addition: Mary Read.

Mary, after her husband's death, joined a merchant ship bound for the West Indies in 1715. In 1720 she met Jack Rackham and joined his crew, dressing as a man alongside Anne Bonny. But, though she was a successful pirate the success was short lived. The pirate ship was captured in autumn 1720, off Jamaica, by a heavily armed privateer. Captain Rackham and ten of his crew were sentenced to death and hanged a few days later. Bonny and Read were tried by the same court on 28th November 1720 and were also condemned to death but reprieved on the grounds that both were, by then, pregnant.

Mary Read died of a violent fever while in prison and was buried on 28th April 1721. There is no record of her child suggesting she died while pregnant. Anne's father, using his influence, managed to obtain her rapid release and return to Charles Town, South Carolina, where she gave birth to Rackham’s second child. On 21st December 1721 she married a local man, Joseph Burleigh, had eight more children and became a respectable woman. She lived on in South Carolina to the age of 84 and was buried there on 25th April 1782.

Running away to sea - for love and adventure

But dressing up as men was not limited to Anne Bonny and Mary Read. In fact, the more you dig into the history of the subject the more fascinating it gets. On 2nd September 1815, the Morning Post published an article in its paper about a sailor called William Brown - a black woman who had apparently served as a seaman in the Royal Navy for eleven years. All of this apparently started from an argument with her husband, who later contested the prize money she earned while serving on the Queen Charlotte.

How much of this is true we do not know but we do know that, according to the muster rolls of the Queen Charlotte (held in the National Archives), 21-year-old William Brown was ‘paid off’ from serving on account of being a woman.

Though we do not know her real name, ‘William Brown’ was not alone in taking to the seas because of a man. In fact, it seemed to be a running theme.

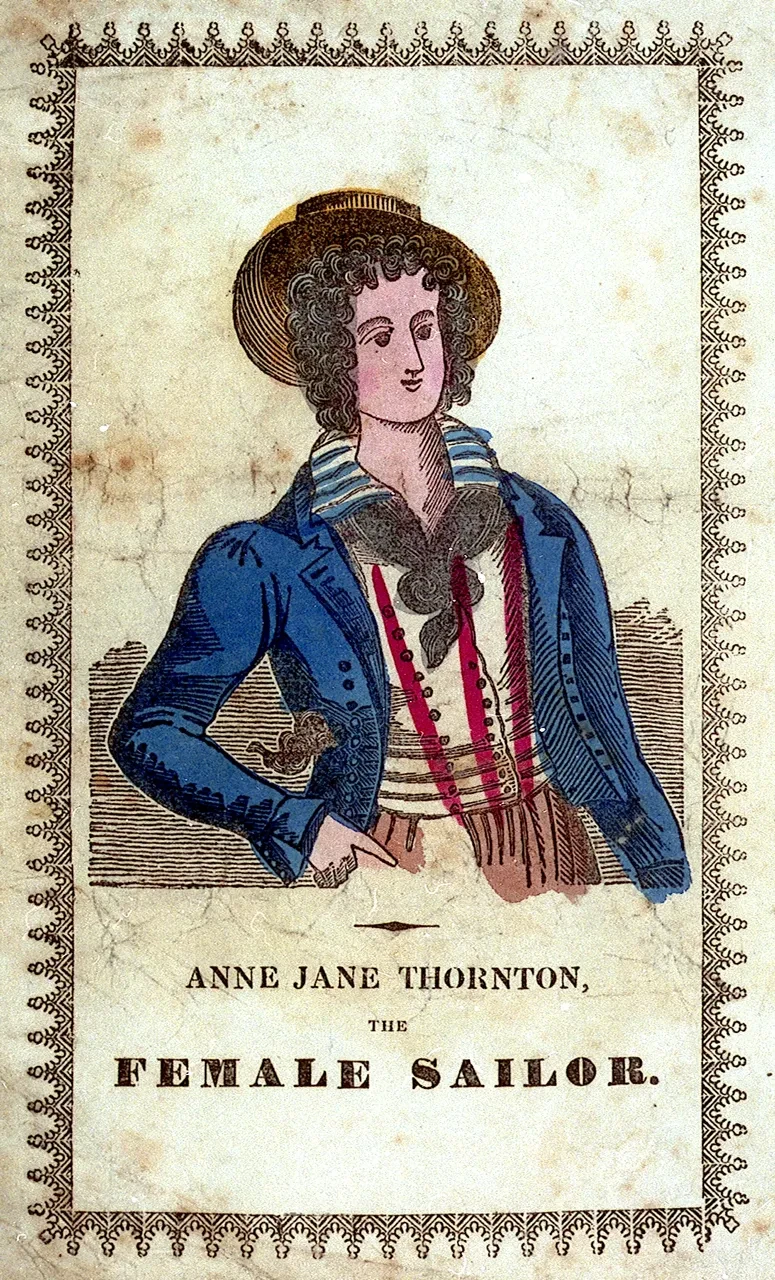

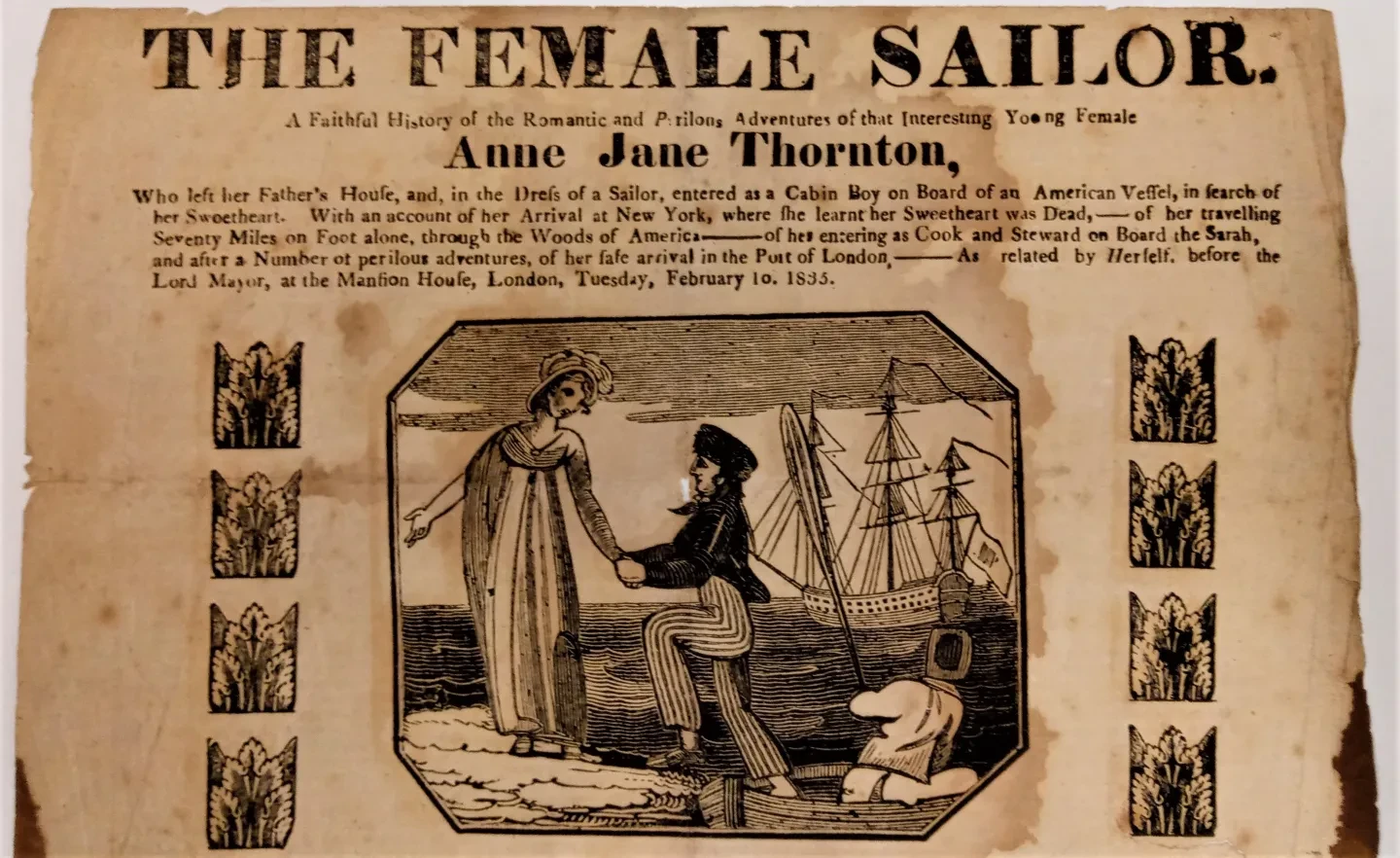

Anne Jane Thornton was a girl on a mission to track down the man she loved. Born 1817 in Gloucestershire she was the daughter of a shopkeeper. At the age of 6 her family moved to Donegal in Ireland when her mother died. By the age of 13 she met Captain Alexander Burke and by 15 she was in love with him. Her heart broke however when he set off to New York to see his father. This romantic girl was not going to be left behind, and it did not take her long to come up with a plan to track him down.

In 1832 she donned cabin boy clothes and found her way to New York only to be told that her love had died a few days before. Without money and a place to stay (and still posing as a boy), Anne got a position as ship's cook and steward on board The Adelaide, where she earned nine dollars a month. She hopped from one ship to another, serving on vessels including The Rover and The Belfast, until she found a ship heading for London. She eventually took a position as a ship's cook on another ship, The Sarah, and gave her name as Jim Thornton from Donegal.

It was on The Sarah that she was discovered. Many newspapers at the time published the story. According to a report in the Manchester Times on 14th February 1835, Captain McIntire said that he was the last person to know on the vessel and could not believe the mate when he was finally told. It is hard to tell how much of this story was true but it, without a doubt, sparked the imagination of the British population who wrote songs about her and even went to see her on stage tell her tale.

Not all female sailors met a happy ending, as in the case of Rebecca Young. Better known as Billy Bridle, she served a few years on a hatch boat. Her death was reported on 20th June 1833 in the Morning Post after an Inquest held at the Town Hall in Gravesend. She and another member of the crew had climbed to the topmast cross tree, for reasons unknown. The man was called back down after a few minutes and after some time at the top Rebecca followed. Unfortunately, it would seem she developed rope burn on the way down and let go of the rope falling a height of 20 feet, she died instantly. Her death was recorded as an Accidental Death and she was buried at St George's Church in Gravesend alongside other sailors and Pocahontas.

A certified female shipwright

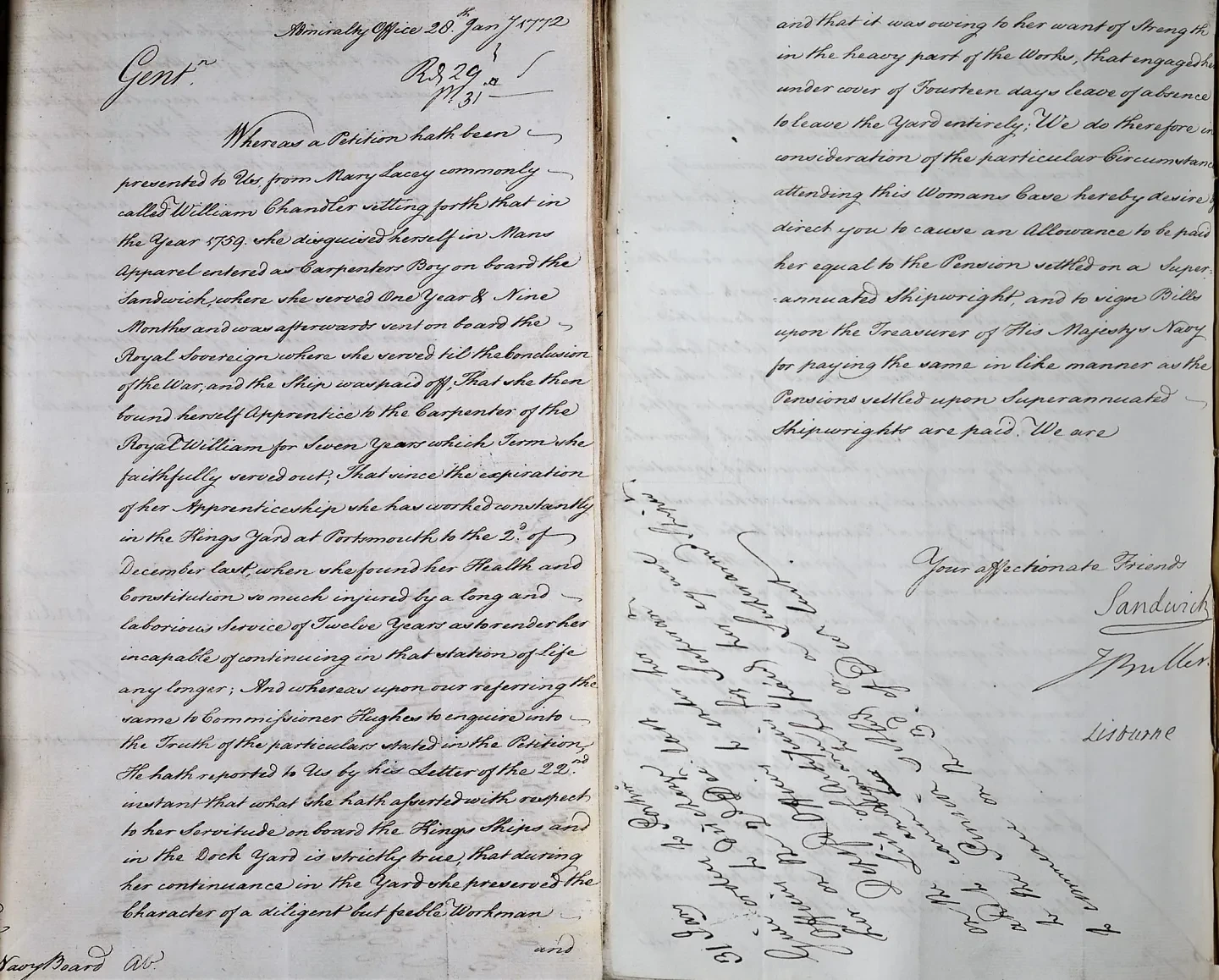

One woman however for me stands out from the rest. Not because she went to sea looking for a lost love or because of an argument. She stands out by just how successful she became; she was a sailor, passed exams to become a shipwright and eventually on discovery of her gender, she was granted a pension from the Admiralty.

Mary Lacy (1740-1795) even wrote her own memoirs entitled "The history of the female shipwright" - a copy of which can be found in the Caird Library. In these memoirs, Mary states that she was born in Wickham and then moved to Ash in Dover a few years later (although her Baptism records show she was born in Wickhambreux, a little village in Canterbury about 40 minutes’ walk to Ash). Her parents were William Lacey and Mary Chandler and she had one younger brother and one younger sister.

In her memoirs, Mary described herself as a wild child that her mother struggled to control. It must not have been too much of a surprise then when Mary donned a pair of breeches, took up the name William Chandler and ran away to sea at the age of 19. She states it was because of a one-sided crush she had on a friend who did not feel the same way. Dressed as a man she walked to Chatham and eventually found her way onto the Sandwich. The navy at the time wouldn’t have asked too many questions as at the time it was engaged in the Seven Years War and active in North America, the Caribbean, Africa, India and the Channel. She was servant to the ship’s carpenter, a Mr. Baker.

By her own account Mary went through many hardships, from a fist fight to a serious attack of rheumatic fever which got so bad by 1760 she ended up in hospital. After recovering she was assigned to the Royal Sovereign. She remained there until the end of the Seven Years War when she was released from the navy. You would think at the end of such uncertainty Mary Lacey would have packed her bags and headed home, but that was not her plan.

Robert Dawkins, a friend she had made on the Royal Sovereign, helped Mary get an apprenticeship as a shipwright at Chatham Dockyard and a place living on board the ship the Royal William. She worked hard and, though almost getting caught some time in 1767-1768, Mary passed her shipwright exams in 1770. Unfortunately, her successful career came to a grinding halt when she was once again struck down by illness from the war. Knowing she would not be able to keep working, she applied for a pension from the Admiralty, explaining her circumstances in full.

After a brief investigation she was granted the full pension equal to that of a Superannuated Shipwright. Mary’s memoirs end with her collecting her pension from Deptford where she meets a shipwright by the name of Josiah Slade and marries him on 25th October 1772. They had 5 children together. She did not however retire quietly. The Admiralty records show that on the odd occasion Mary petitioned on behalf of her husband, showing that she was still a shipwright at heart. Mary was buried on 3rd May 1801 in St Nicholas Church, Deptford.

These women each with their own unique story do not stand alone. They stand with Mary Anne Arnold, daughter of Lieutenant Arnold, who ran away to support her family after her parents died. Hannah Snell, who followed her husband after the birth and suspected death of their child. Hannah joined the army in 1745 under the name of James Gray. Later she joined the navy as a cook's assistant and then became a common seaman, spending a total of nine years at sea. They also stand with Mary Anne Talbot, who became a soldier and sailor during the French Revolution.

All these women had one thing in common. They would not let anything stand in their way.

Newspaper records taken from the electronic resources at the Caird Library. For further information about electronic resources at the Caird Library and Archives see: Caird Library and Archive - electronic resources.

Banner image: Mary Read