A slave plantation manager's letters home reveal attitudes towards enslavement and emancipation.

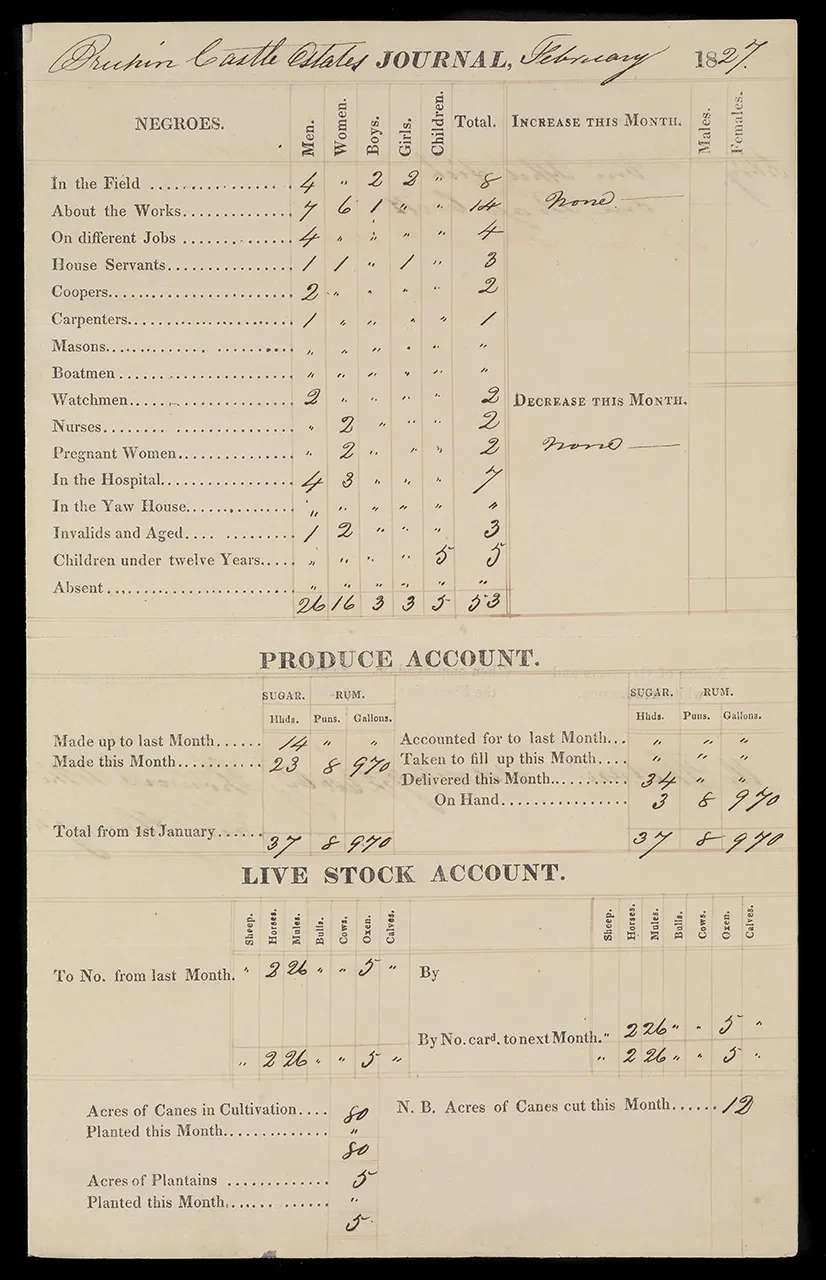

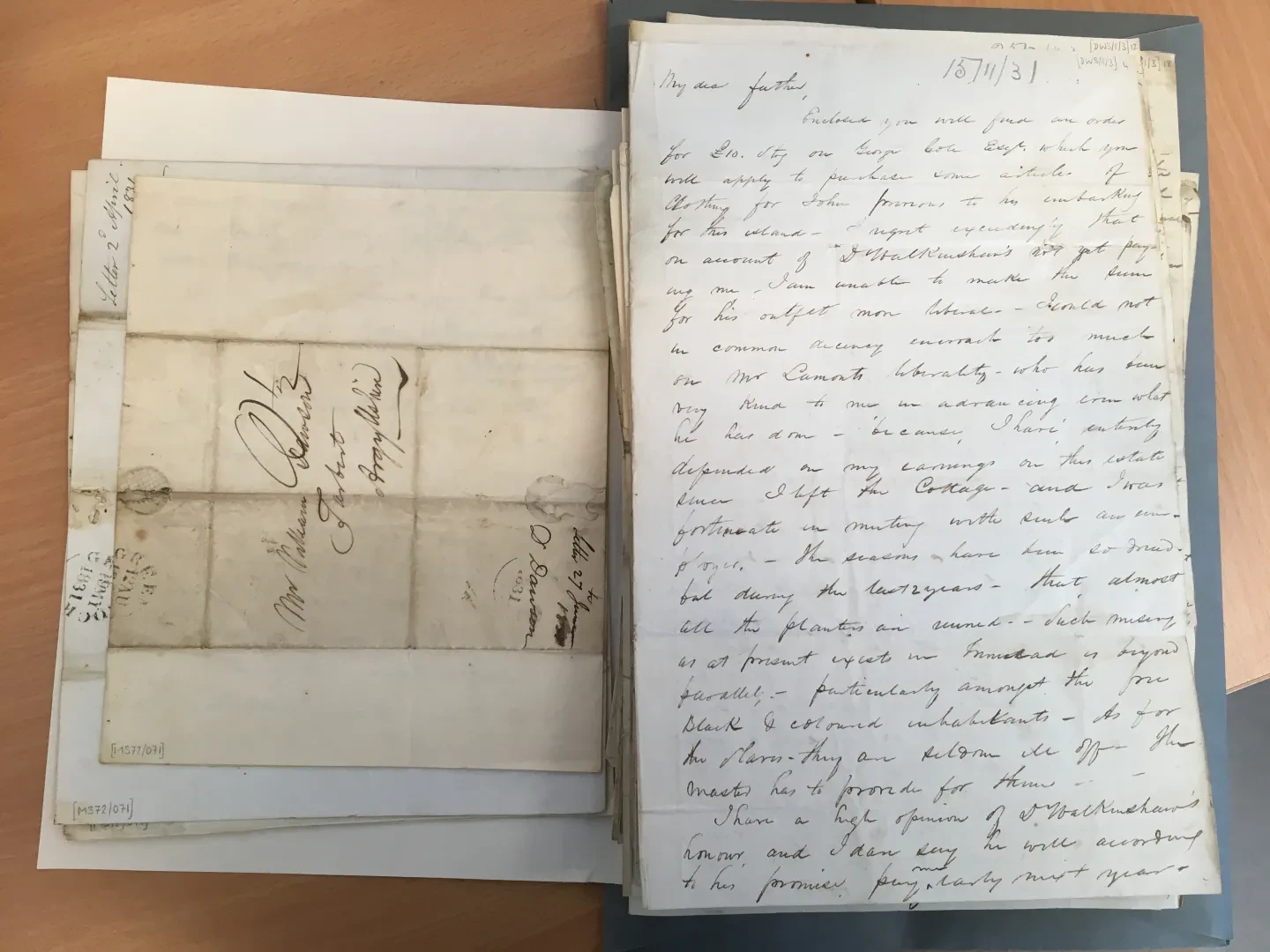

In this month’s blog, we look at the letters of Dugald Dawson (DWS/1/1-3). These letters offer a glimpse into the life as an overseer on a plantation – possibly the only account of its kind in our collections.

Overseers were the middlemen of the plantation hierarchy; they had to produce profitable crops while controlling enslaved people and directing their work. Dawson seems aware of the unsustainable contradictions of the job, and offers an interesting position from which to view the abolition of a system in which he was employed.

His eyewitness account of plantation life in Trinidad comes during a crucial chapter in the wider story of British slavery. These letters were written after Britain had banned its subjects participating in the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, but before freedom was granted to enslaved people in 1833.

The papers also contain a single letter by John, younger brother of Dugald, who joined him in Trinidad in 1832, and had a different perspective.

Early years in Trinidad

Dugald arrives in Trinidad in 1823 having secured a job as an overseer at Jordanhill, a sugar cane plantation. He describes a 'little gang' of enslaved children who help him look after the mules, and seems charmed by the place.

In early 1824 he is keen to show his father how much he has learnt of his new role, and describes in detail the harvesting of the cane and boiling of the juice - backbreaking and dangerous work undertaken by enslaved people. He regularly asks his father to send him clothes and shoes. He seems to wear out and ruin them a lot more quickly than he imagined, as the work is hard and there are frequent rainstorms that turn the roads to mud.

In November 1825, he is grieved to tell his father of the death of a fellow overseer, Mr. Henderson. Dugald makes the following rather chilling comment that reveals something of his attitude to the enslaved people of Trinidad and, perhaps, something of their attitude to white employees:

I am not superstitious but I should not like to die in this country – the creatures that attend your dying moments are as unfeeling as stone – no tears at human agony bedew their black cheeks. An utter indifference to his living or dying pervades their whole frame and they are probably calculating upon the gain which they may make by his death.

Perceived differences between the West Indies and Britain

He goes on to describe other ways in which the West Indies are different to Britain, concluding that he would recommend them to no one, and if his younger brothers were expecting him in the coming years to set them up with jobs like his, he would encourage them instead to stay in Britain. He also writes of a recent earthquake that has greatly worsened living conditions in the area, and regularly complains about his low salary and lack of intellectual stimulation.

Despite this, his employer is impressed with him and rewards him in June 1826 with a generous bonus. He reads in a newspaper about the working conditions and hunger of the 'manufacturing classes' in Britain, and goes as far as to make this crass observation:

… alas how different from the plenty abounding amongst our labourers here. Many would I am sure willingly change places with them, unaccompanied by the abasing epithet of slave – so harsh to British ears.

The Dawson brothers in Trinidad

By March 1828, he has moved to a different estate, Clydesdale Cottage, and is now the sole overseer, which means a better salary. In 1830, he remarks that his brother John must now be 'near an age at which young men generally come to the West Indies' and, contrary to his opinion a few years earlier, suggests that he should come to Trinidad, as he has a prospect of an even better position, which would mean John could comfortably settle there.

Later that year, however, he writes from his new location, River Estate, Diego Martin, with news that the entire island has suffered a disastrous harvest, and that many planters fear unemployment. By April 1831, he is of the opinion that:

With respect to John – bad as the West Indies are – I believe home is little better … I must make preparations to have him out here … I have little doubt of procuring a situation for him in the same employment as myself which is amongst the best in the Island.

In November 1831, in a letter in which he mostly discusses the details of John’s passage to the Caribbean, he observes:

Such misery as at present exists in Trinidad is beyond parallel, particularly amongst the free Black and Colonial inhabitants. As for the slaves, they are seldom ill-off – the master has to provide for them.

Differing opinions

John arrives in February 1832. In a letter notifying their father of his safe arrival, Dugald complains that the ministers in Britain who are set on emancipation 'know nothing of our local circumstances', and that the slaves 'hearing that a law has been made in their favour … expected greater things than the law contained'.

He worries about John’s prospects given the situation, but he still feels this is a good opportunity for his poorly educated brother to gain some experience.

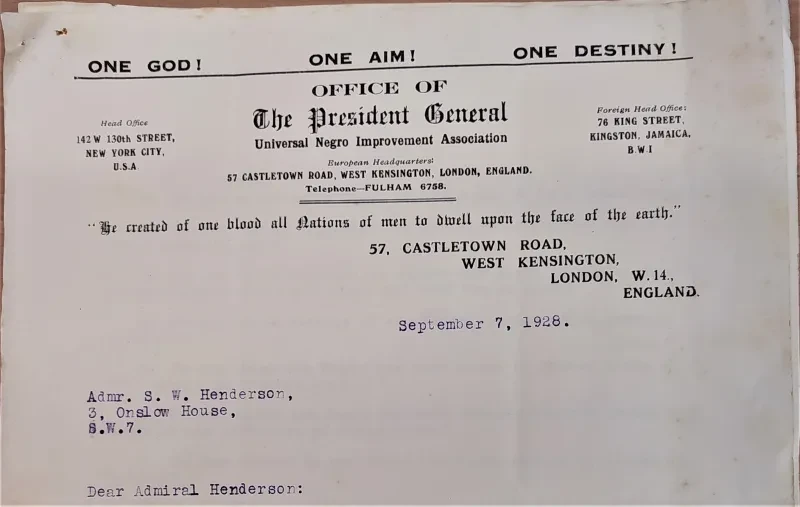

John Dawson, writing in July 1833 from Trinidad, expresses his own feelings about the latest Abolition Act and consequences thereof:

… the West India colonies are going to destruction as fast as the English ministry are able to form laws and regulations. As for my part, what need I care much about it, I have no property at stake … I wish the system was at an end, if they could be liberated with safety and be made useful subjects after their freedom to work as free labourers.

Dugald, by contrast, seems to care a great deal about the effect of the emancipation on the general mood on Trinidad. In a letter written in July 1833, he writes:

The slaves are at present quiet – but they are aware that their freedom is about to be given them and they are waiting patiently until it be proclaimed. How they will like the restriction of unlimited freedom – by being obliged to work for their masters for twelve more years – will then be known.

This fear was probably felt by the white population on the islands, particularly overseers, who had to introduce a new system of apprenticeship to the enslaved people, prolonging their suffering under the guise of emancipation.

Finally, in November, he writes:

We are anxiously awaiting the first of August 1834, when the slaves will become apprentices.

The Abolition Act

Abolition was a chaotic affair, which did not bring an end to the suffering of enslaved people, and the apprenticeship system prolonged unfree labour and inequity.

If you would like to find out what happened in the years following the Abolition Act of 1833, Dugald’s letters continue until 1840. You can read these here in the Caird Library by registering as a reader and ordering item DWS/1/1-3.

If you would like to read accounts by black abolitionists, Royal Museums Greenwich holds the published accounts of Mary Prince and Olaudah Equiano, but very few accounts exist due to the restrictions imposed on enslaved peoples’ education.

Current opening hours and visiting instructions can be found here.