One of the many treasures to be found in the collections of the Caird Library is John Pine's The tapestry hangings of the House of Lords: representing the several engagements between the English and Spanish fleets in the ever memorable year 1588 (RMG ID: PBE3597)

A rare folio published in 1739, it contains print reproductions of the ten enormous tapestries that once hung in the old chamber of the House of Lords. For 183 years (1651-1834) the tapestries wove themselves into the fabric of British political and cultural life, appearing in a number of artworks and referenced in parliamentary speeches.

By Shane McMurray, Library Assistant

Visit the Caird Library and Archive

John Pine, Clement Lemprière and Henri Gravelot. Plate V: San Salvador of the Guypuscoan Squadron, being set on fire, is taken by the English. Etching, 1739 (RMG ID: PBE3597)

In 1591, to commemorate victory over the Spanish Armada, the Lord High Admiral Charles Howard, first earl of Nottingham commissioned a series of ten tapestries from Francis Spierincx at a cost of £1582. The Delft-based Spierincx engaged the talents of Dutch marine artist Hendrik Vroom to produce a number of cartoons (designs) depicting the Battle of Gravelines. The cartoons, now lost, were used by Spierincx as a template for creating the tapestries. Completed in 1595 they hung at Arundel House, Lord Howard’s residence in the Strand, before being sold in 1612 to James VI & I for £1628.

With the execution of Charles I in 1649 the tapestries escaped the great Commonwealth sale and by 1651 the majority of them were placed in the Queen’s Chamber, recently vacated by peers following the abolition of the House of Lords. Oliver Cromwell appears to have favoured tapestries over paintings and may have recognised the symbolic importance of the works to the nation. Following the Restoration in 1660 the tapestries remained as peers re-established themselves.

With the British-Irish union in 1801 peers had to move to the larger White Chamber (formerly the Court of Requests) to accommodate an increase in membership. The tapestries, having become an integral part of the furnishings of the Lords chamber, moved with them. The larger space also provided the opportunity for all ten tapestries to be displayed.

These great Renaissance works have since been lost to history, destroyed in the fire that burnt down most of the medieval parliamentary estate in 1834. Overnight Pine’s engravings, produced a century earlier in exquisite detail, became a vital visual record of the original works.

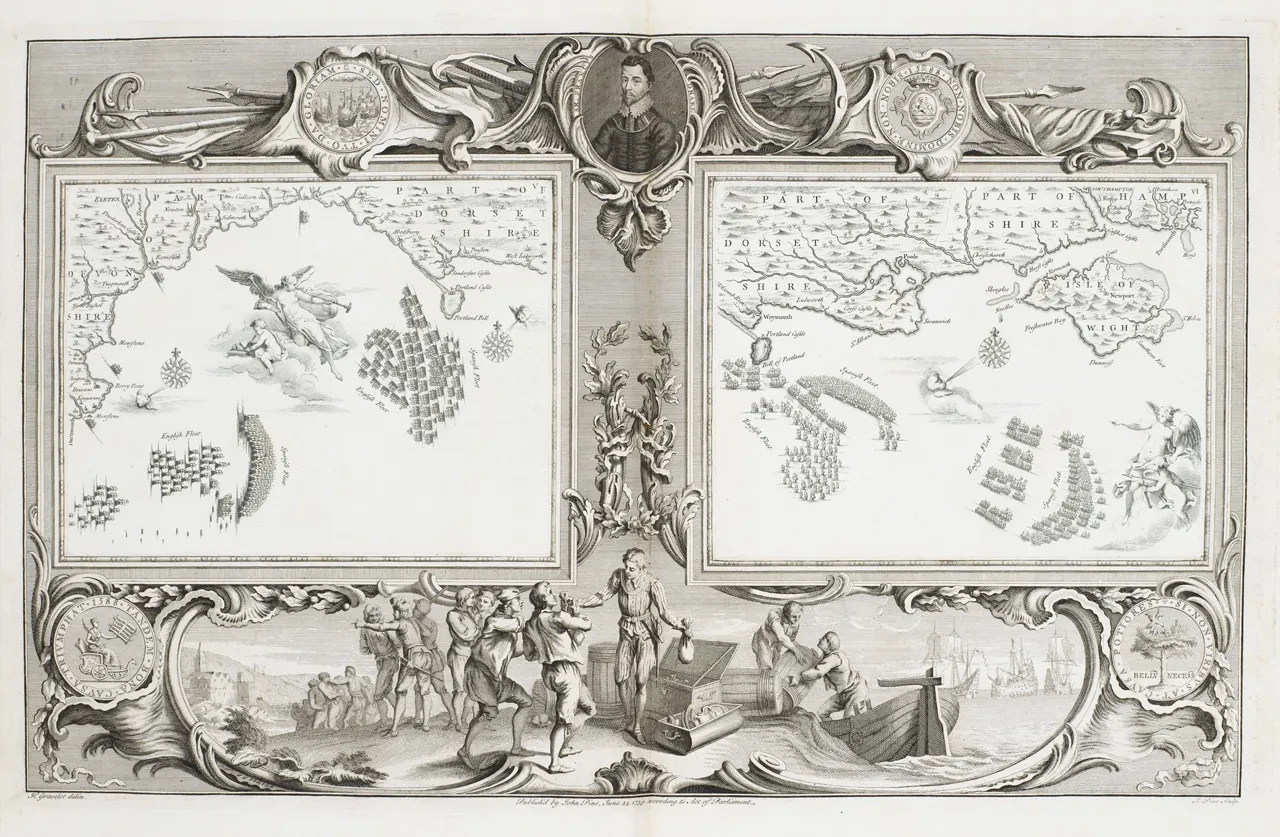

John Pine and Henri Gravelot. Charts V & VI: Capture of San Salvador and the action off Portland. Etching, 1739 (RMG ID: PBE3597)

John Pine (1690-1756) was an engraver and publisher. A friend of William Hogarth, he served as a governor of the Foundling Hospital and was involved in early discussions that ultimately led to the formation of the Royal Academy of Art.

In 1739 he published his most famous work, The tapestry hangings of the House of Lords. It was a project that took at least four years to realise. Utilising his influence as part of Hogarth’s circle, he petitioned Parliament to have a clause inserted into the Engravers’ Copyright Act 1735 granting exclusive rights to copy the tapestries:

V. And whereas John Pine of London, engraver, doth propose to engrave and publish a set of prints copied from several pieces of tapestry in the house of lords, and his Majesty’s wardrobe, and other drawings relating to the Spanish invasion, in the year of our Lord one thousand five hundred and eighty eight; be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That the said John Pine shall be intitled to the benefit of this act, to all intents and purposes whatsoever, in the same manner as if the said John Pine had been the inventor and designer of the said prints.

Judging from the long list of subscribers, it was a rather popular venture. Many of those who supported the project were leading political figures of the day including Frederick, Prince of Wales and Britain’s first prime minister Sir Robert Walpole.

John Pine after Joseph Ames and Robert Adams. Thamesis Descriptio Anno 1588. Etching, 1739 (RMG ID: PBE3597)

The folio begins with a historical account of the ‘Spanish Invasion’, promising sources were ‘collected from the most authentic Writers and Manuscripts’. It goes on to describe the defeat of the Spanish Armada and the preservation of the victory for posterity as

'the most glorious Victory that was ever obtained at Sea, and the most important to the British Nation… Our Ancestors… careful it should not pass into Oblivion… procured the Engagements between the two Fleets to be represented in ten curious Pieces of Tapestry…which are now placed… in the House of Lords, the most august Assembly of the Kingdom, there to remain as a lasting Memorial of the Triumphs of British Valour, guided by British Counsels.'

The Armada tapestries are reproduced across ten plates. Working from drawings made by Clement Lemprière each scene captures a moment during the confrontation. Portraits of Lord Howard, Sir Francis Drake and others adorn the borders. In addition to the plates ten corresponding charts illustrate the progress of the opposing fleets up the English Channel. Also included are several maps: one indicates the path of the Armada around Britain and Ireland, while others mark defensive positions along the Thames and English coastline that were prepared in anticipation of a landing by Spanish forces.

Pine based his engravings on charts created by cartographer and engraver Robert Adams, Queen Elizabeth’s Surveyor of Buildings. They were produced under the direction of Lord Howard shortly after the Armada and published in Expeditionis Hispanorum (RMG ID: PBD8529). When creating his cartoons for Spierincx a few years later Vroom was given a set of Adams’ charts to work from.

At the time of publication, the political landscape was unstable. After nearly twenty years in office Walpole’s power had waned. His political opponents were pushing for a declaration of war against Spain over an incident involving Robert Jenkins, a Welsh mariner, who had his ear severed by a Spanish captain in 1731. The War of Jenkins’s Ear (1739-40), as it later became known, was soon enveloped by a wider European conflict over the Austrian succession (1740-48). Pine’s dedication to King George II acknowledges the political climate and the success of the project would have benefited from anti-Spanish feeling.

James Gillray. Consequences of a Successful French Invasion. Watercolour, 1798 (RMG ID: PAG8509)

Notably, the tapestries themselves have appeared in several works over the centuries. Peter Tillemans’ Queen Anne in the House of Lords (1708-14) or John Singleton Copley’s dramatic Death of the Earl of Chatham (1779-81) give an indication of the dominant presence the tapestries occupied in the chamber. One particularly vivid depiction by caricaturist James Gillray demonstrates the political significance the tapestries had acquired. Consequences of a Successful French Invasion offers a startling vision of French troops in the House of Lords, ripping down the tapestries and setting them alight.

However, Pine’s engravings provide the crucial visual record. When work began on the new Palace of Westminster following the 1834 fire Prince Albert’s Fine Art Commission envisioned a scheme in the Prince’s Chamber that would faithfully reproduce six of the tapestries as paintings. Initially only one panel was executed, with the remaining five completed between 2007-10. The artists involved used Pine’s engravings as reference. Without them the scheme could never have been realised.

Further Reading

- Engravers' Copyright Act 1735, 8 Geo.II c.13. Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), ed. L. Bently & M. Kretschmer. www.copyrighthistory.org. Accessed 22 Aug 2019.

- Hay, Malcolm. The Armada Tapestries: A Project to Recreate the Armada Series for the Prince's Chamber in the House of Lords. London: Palace of Westminster, 2008/09.

- Rogers, Phillis. The Armada Tapestries in the House of Lords. RSA Journal, Vol. 136, No. 5386 (September 1988), pp. 731-735. JSTOR. Accessed 17 May 2019.

- Sloman, Susan. Pine, John (1690-1756), engraver. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sept 2004. Online. Accessed 27 June 2019.

- Woodfine, Philip. Britannia’s Glories: The Walpole Ministry and the 1739 War with Spain. Woodbridge: Royal Historical Society, 1998.