Heavily contested at the time of its creation, crafted in secrecy and rebellion, the text of this document is now well known the world over.

By Martin Salmon, Archivist

Plan a visit to Greenwich from the US

So often the case in the archives, it’s not the document itself, but the story that goes with it that’s most interesting!

Although not the only copy in British archives or even the only handwritten copy, it is just possible this was the very first text of the Declaration of American Independence to reach British shores (Archive catalogue Reference SAN/F/9/16). Yet it’s the accompanying letter that’s in some ways even more interesting, because it gives insight into the timing and circumstances in which the document was created.

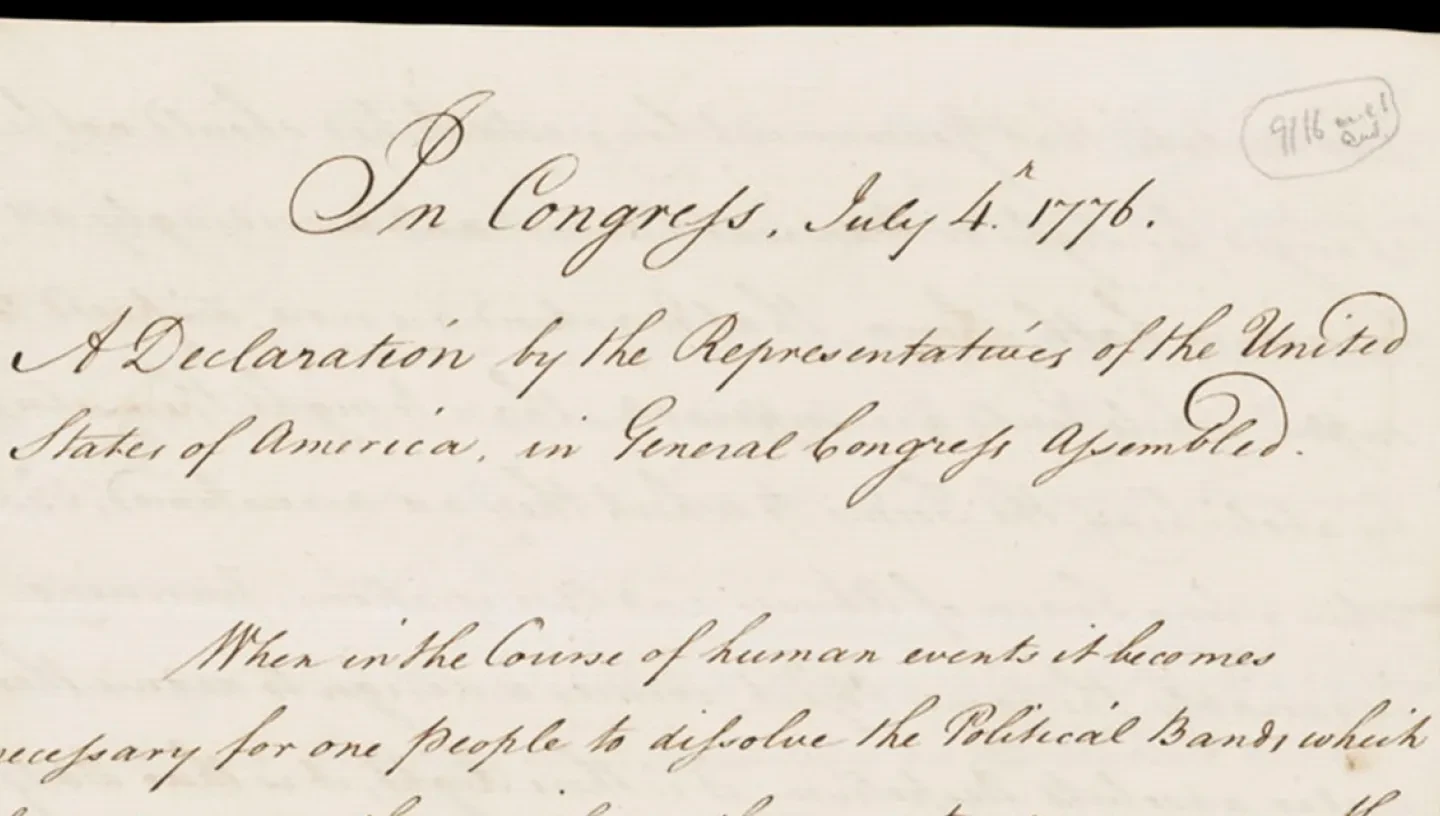

The Declaration of American Independence was drafted by Thomas Jefferson in June 1776, drawing upon ideas developed by European philosophers about individual liberty. The declaration states that “all men are created equal”, before listing the complaints against the British Crown that were to justify the breaking of the ties between the American colonies and Great Britain. This handwritten copy of the Declaration was sent to the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, and may have been the first report of American independence to reach Britain.

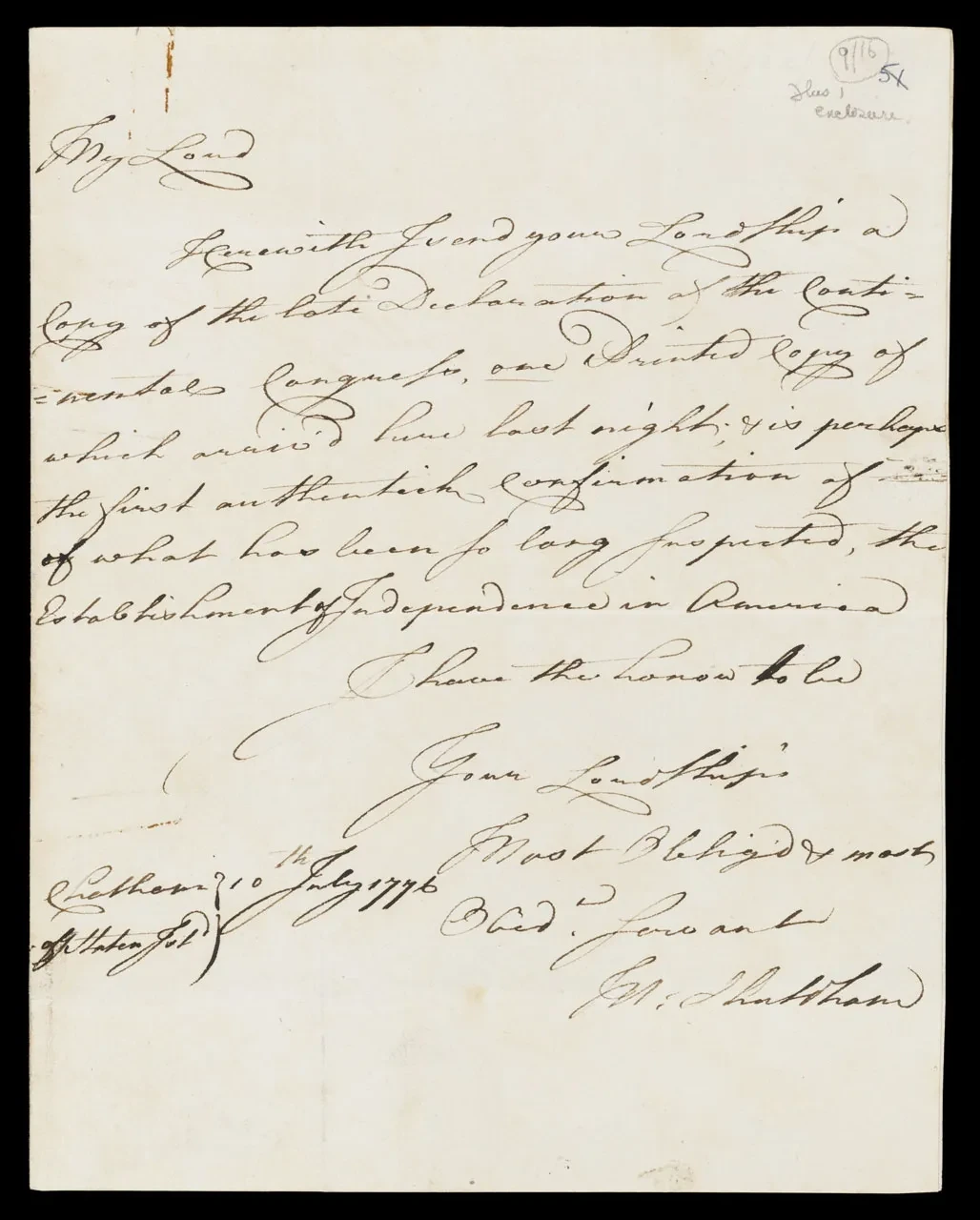

The letter which accompanies it is dated 10 July 1776.

The Declaration was first printed on 4 July 1776 in Philadelphia. Known as the Dunlap Broadside, 26 of these printed copies now survive. The first Dunlap Broadside to reach Britain is now at the National Archives among the papers of the Colonial office (forerunner of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office).

The note accompanying it is dated 11 August 1776 and reads ‘A printed copy of this Declaration of Independence came accidentally to our hands a few days after the dispatch of the Mercury packet, and we have the honor to enclose it.’ The fact that there is no comment on the contents or significance of the document (other than to state it is a printed version) strongly suggests that the Dunlap copy was not the first news of the document to arrive in Britain, but ‘merely’ the first printed version. It also suggests that something else on the subject did travel by the Mercury Packet…

Dated 10 July 1776, the accompanying note does indeed highlight the significance of the Declaration:

My Lord / Herewith I send your Lordship a Copy of the late Declaration of the Continental Congress, one printed copy of which arriv’d here last night, & is perhaps the first authentick confirmation of what has been so long suspected, the establishment of Independence in America.

The letter is signed Molyneux Shuldham, [HMS] Chatham off Staten Island, 10 July 1776. Vice Admiral Molyneux Shuldham commanded the British naval forces blockading New York at this time. Clearly there wasn’t anything wrong with the British intelligence network in Philadelphia. Within 5 days of it being published, a copy of the Dunlap Broadside had been obtained, brought a distance of 90 miles to New York, made its way out to the blockading squadron and was transcribed on the way to England! It is likely that several copies were made by hand and sent to England. With uncertain communications in war time, it made sense to send several separate copies of any correspondence, official or personal, giving intelligence the greatest chance of getting through.

Interestingly, though Molyneux Shuldham was relieved of command in June 1776, his replacement, Vice Admiral Howe did not arrive in America until 12 July 1776, two days after Shuldham’s letter was written. It is likely therefore, that among the very lasts acts of his command was to ensure the intelligence of American independence being fact, was communicated home by the Mercury.

Lloyd’s List for 1776 confirms that the Falmouth Packet Mercury did indeed depart New York on 9 July 1776 and it seems reasonable to suppose the following day the Mercury paused to collect the mail from the Shuldham’s blockading squadron off Sandy Hook, arriving at Falmouth a month later. Probably without knowing, the Mercury may have been the vessel that brought the first news of Independence in America.

Please note: this item is not on public display and in order to see it you must request an appoitment by contacting the Caird Library, located at the National Maritime Museum.