The Moon and its light have inspired illustrations, paintings, and woodblock printings. Discover this connective force in art through the artworks of Turner, Rubens, Yoshitoshi and many more.

By Carla Valois Lobo

The Moon is a source of communion between humankind and nature. It also connects people across borders in its thread of beaming, volatile silver. This atmospheric effect of moonlight has inspired a multitude of artists in media such as illustration, painting, and woodblock printing.

Night-time compositions transform a banal scene into a view of mystery. Moonlight fills a canvas with an aura of nostalgia and melancholy. It helps to mimic a quality of fleeting romance by turning a transitory moment into almost palpable, tangible.

Yet, moonlight cannot be grasped. It is elusive; it belongs to the reign of the ephemeral, even if through its cyclical patterns it might deceive you otherwise.

Moonlight in art: Turner, Constable, Rubens and Friedrich

Western Masters such as J.M.W. Turner, Peter Paul Rubens, John Constable, and Caspar David Friedrich were more than intrigued – they were mesmerised by moonlight. Their landscapes attempted to hold its never-ending incarnations within the boundaries of materiality, circumscribed in paintings and watercolours of pale blue, green and grey hues.

In the oil on canvas Fishermen at Sea (1796), Turner depicts a small fishing boat struggling against the waves of an open, violent sea. In spite of carrying a flickering lantern, the fishermen are lit by a bright Full Moon, which safeguards them but also reveals the dangers ahead. The painting stresses their vulnerability in relation to nature. In fact, in a broader sense, it emphasises humankind’s subjugation towards the cosmos and its power.

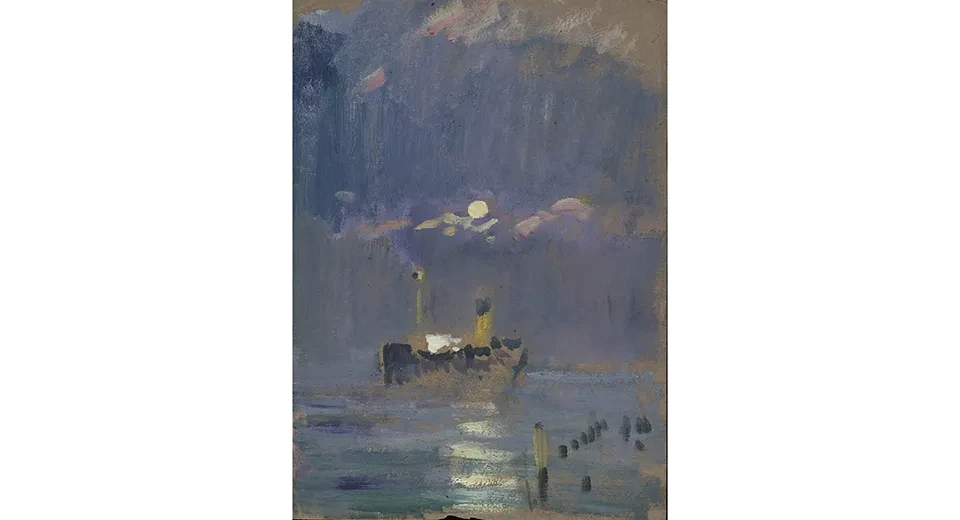

Similarly, in the gouache and watercolour on wove paper Moonlight on River (c. 1826), Turner summons the brevity of moonlight by conveying ‘the physical sensation of light coruscating across the sky and glistening in the water below’ according to Royal Museums Greenwich curator of art Melanie Vandenbrouck. This night-time composition evokes a scenery of transience.

Prior to Turner, in the 17th century Rubens brought Landscape by Moonlight (1635-40) into life. An idyllic view occupies this nocturne: a starry sky, a vivid Moon reflected on a lake, a horse in the shore and green, placid trees in the waterside. The oil on panel pastoral was a response to Flight into Egypt (1609-10), an oil on copper cabinet painting by German artist Adam Elsheimer. In his turn, Rubens was an influence on Constable, suggests Vandenbrouck.

Netley Abbey by Moonlight (c. 1833), a graphite and watercolour on paper by Constable, radiates an other-worldly atmosphere that is intensified by moonlight. Constable and his wife, Maria Bicknell, visited Netley Abbey in 1816. He made a number of pencil studies at the time, but the watercolour was made much later.

In 1828, aged 41, Bicknell died of tuberculosis, leaving behind seven young children. Netley Abbey by Moonlight is hence a sort of visual elegy. The blurry figure in front of a gravestone accentuates the sense of loss, as does the palette dominated by cool blue hues.

A much warmer range of colours was adopted by Caspar David Friedrich in his Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1819-20). A well-known painting within German Romanticism, this landscape oil on canvas is the first of a series of three; the other two followed in 1824 and 1825-30. It depicts a couple of friends on a mountain path, seen from behind, gazing at a waxing Moon during nightfall. The composition is yet another example of human communion with nature, inviting the spectator to join the figures in their evening observation.

In a similar fashion, The Lady in Milton’s ‘Comus’ (1784-5 and 1789), by Joseph Wright of Derby, ‘conveys the feelings of the subject represented and in turn affect the emotions of the beholder’, writes Vandenbrouck in the catalogue of The Moon exhibition.

In The Lady in Milton’s ‘Comus’, Wright presents a young woman, ‘Lady’, alone in the woods and lost in the wilderness. She has been separated from her brothers and, fearing the debauched Comus, looks at the Moon in order to plead for safety. While the moonlight could be said to be protecting her, it also increases the tension of the scene, eliciting apprehension and pathos from the viewer.

Beyond Europe: Moonlight in Eastern art

In Japan, the Moon has been a source of inspiration to many artists from as early as the 15th century (such as New Moon over the brushwood gate, an ink on paper from 1405). Names such as Nishimura Shigenaga, Utagawa Yoshitaki, Suzuki Harunobu and Utagawa Hiroshige are amongst these.

In 1789, Ki no Sadamaru collected 72 Kyōka (or parodic) poems related to the satellite and published them in the anthology Ehon kyogetsubo 絵本狂月坊. Kitagawa Utamaro contributed by providing five Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) woodblock prints with the recurring motif of the Full Moon.

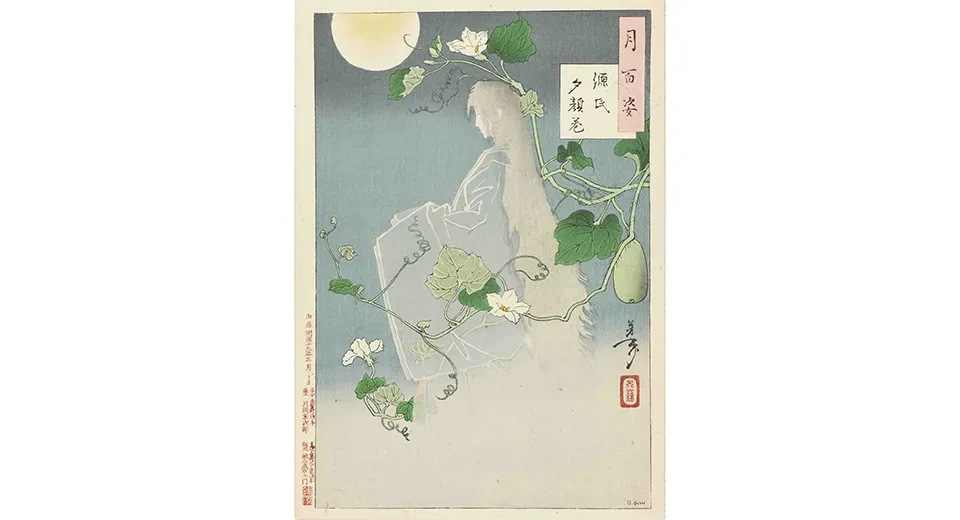

No other Japanese artist went as far in contemplation of the Moon, however, as Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Between 1885 and 1892, he produced a series of a 100 ukiyo-e, colour woodblock prints called Tsuki hyaku sugata 月百姿 (translated as One Hundred Aspects of the Moon in English).

These illustrations deal with subjects such as folklore, literature, and religion. In fact, they are an ode to the Moon and its phases, since Yoshitoshi used the lunar cycle to represent feelings like introspection, loneliness or sorrow. His images featuring a Full Moon thus hold subtle differences in meaning from the ones showing Waning Gibbous or Waxing Crescent Moons.

The Moon was also a muse to a number of artists based in China, India, and Korea. In China, particularly, the Moon has had a special significance for over a thousand years. The satellite is linked with lunar goddess Chang’e (嫦娥) and her companion Yutu (玉兔), a jade rabbit wielding a mortar and pestle that is constantly pounding her the elixir of life.

Yue Lao (月下老人), the god of love and marriage, and Jin Chan (金蟾), a mythical toad, are equally related to the Moon. The depiction of these deities is vital to Chinese iconography, and the portrayal of Chang’e flying to (or over) the Moon has been a constant subject of ink painting since the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

In parallel, Chinese landscape paintings, known as shan shui (山水画, translated as ‘mountain water’ in English), sought to represent the entire cosmos. In this context, moonlight evokes a spiritual connotation, an agency to emphasise inner harmony and tranquillity. In most shan shui, a poem in beautiful calligraphy is included to complement the scenery and explain it. This form of Guóhuà (國畫), as traditional Chinese painting is known today, is strongly informed by Buddhism and Taoism.

From East to West, North to South: the Moon as a connective force

The Moon is much more than a mirror to the Sun. Indeed, it does reflect light, but its gleam has a distinctive and inspiring strength of its own. Long before the advent of electricity, the Moon ruled our night-time activities and, as such, our imaginations.

In painting and printmaking, the allure of the Moon bewitched Baroque, Romantic, Naturalist, Ukiyo-e and Guóhuà artists. The list of painters who employed moonlight in their canvasses is countless, from Vincent Van Gogh (Starry Night, 1889 and White House at Night, 1890) and Henri Rousseau (A Carnival Evening, 1886) to American Modernist Albert Pinkham Ryder (Moonlight Marine, c. 1870-90).

Certainly, as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution, our relationship with the Moon has changed. And yet, the satellite continues to marvel visual artists.

In the midst of a myriad of aesthetical and cultural differences, the Moon remains a connective force. From East to West, its light unifies those living in floodlit cities, tiny fishing villages and remote settlements. As it keeps captivating minds in the 21st century the same way it did in the 1400s or in the 1800s, it will carry on doing so for decades to come.

The Thames and Greenwich Hospital by Moonlight, c. 1854-60, by Henry Pether (1800-80), is a particularly fine example of a nocturne painting owned by Royal Museums Greenwich.

In this oil on canvas, Greenwich Hospital is depicted in the foreground from the west. The architectural details are carefully studied and delineated. The moonlight, reflected from the Thames, illuminates the scene but also creates a ghostly, uncanny atmosphere. The Bellot Memorial Monument, an obelisk unveiled in 1855, can be seen on the right side corner, while the Isle of Dogs lies on the far left. The chimney of the Cumberland Oil Mills, an oil-seed factory that was demolished in the late 1980s, is shown beyond the moored ships.

Pether was the son of English landscape painter Abraham ‘Moonlight’ Pether of Chichester. Like his father, Henry specialised in night-time compositions, adopting the Full Moon as a central motif to his practice. The Thames and Greenwich Hospital by Moonlight is possibly one of his most celebrated pieces.

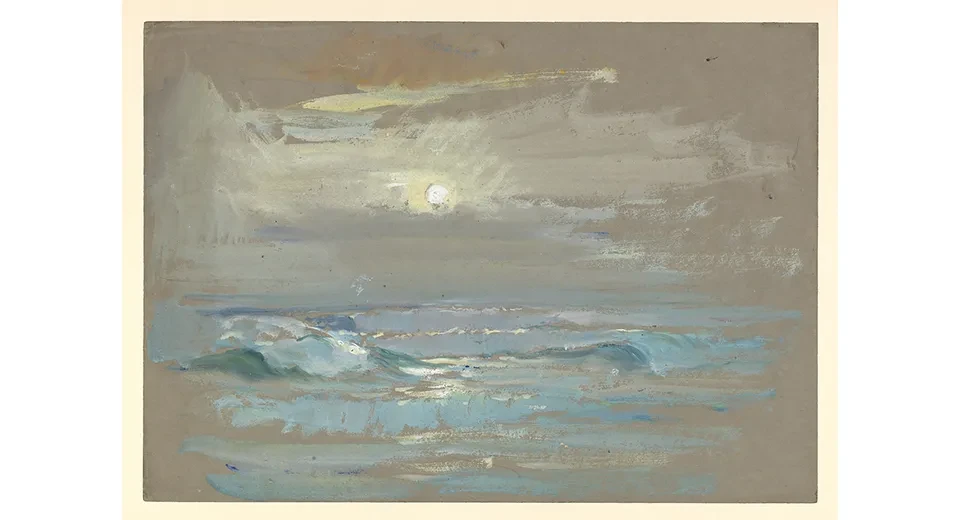

John Everett (1876-1949) is yet another English painter in our collections who produced a number of night-time compositions. Seascape by moonlight (n.d.) depicts a placid expanse of sea illuminated by the light of a bright Full Moon. Different shades of blue and grey dominate this oil on paper, bequeathed by the artist to the National Maritime Museum in 1949.

The Thames and Greenwich Hospital by Moonlight and Seascape by moonlight is on display at the Queen's House. Moonlight on River by Turner and Netley Abbey by Moonlight by Constable, as well as The Eighth Month: Moon viewing (1770-5) by Ishikawa Toyomasa; Endymion and Selene (c. 1870) by Victor-Florence Pollet; Harvest Moon (1855) by John Linnell; and Autumn Evening (1994) by Lee Chong-sop all featured in The Moon exhibition.