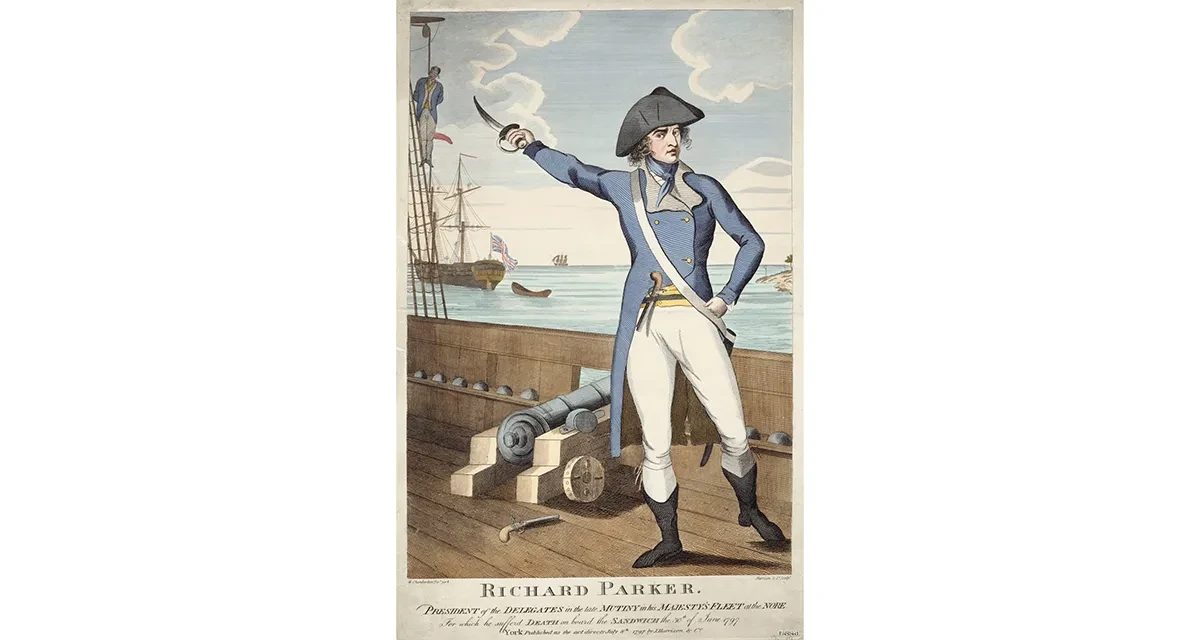

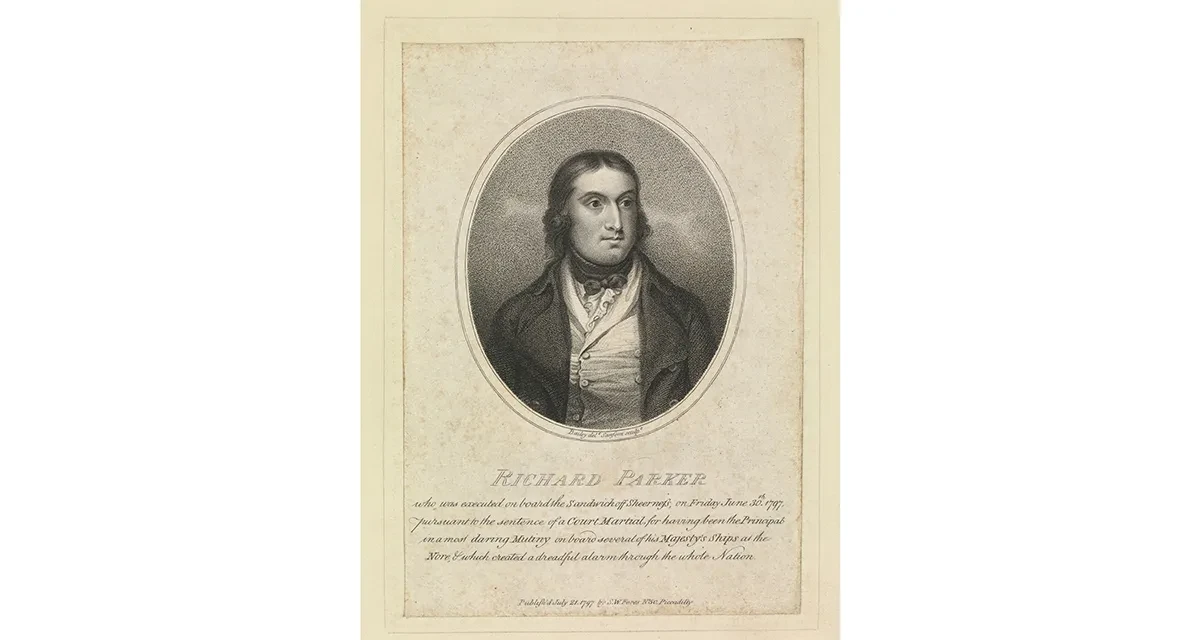

Richard Parker was sentenced to death for his role in the 1797 Nore Mutiny - but was he a ringleader or a scapegoat?

On Friday 30 June 1797, the crews of several of His Majesty’s warships, having been ordered to temporarily bring their vessels to anchor in the Thames Estuary, witnessed the last living moments of one Richard Parker.

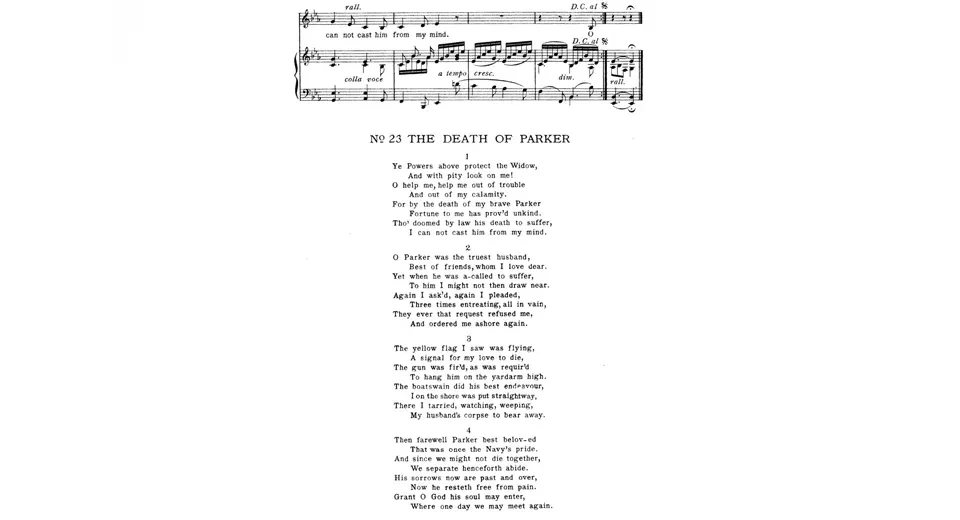

Underneath the fluttering yellow flags of capital punishment, and at precisely half-past nine in the morning, the nominal leader of the Nore Mutiny was hanged aboard HMS Sandwich. His body is said to have briefly convulsed as it was run up the yardarm of the very ship that had acted as the headquarters of his mutinous delegates, just two weeks earlier.

The 1797 mutiny at the Nore was the second large-scale, lower-deck sailor uprising that had threatened the British Admiralty within a month.

The Spithead and Nore Mutinies

The first mutiny at the Spithead anchorage in Portsmouth had come to a peaceful conclusion amidst fears of an imminent French invasion. Thus, it seemingly appeared to all of Britain that the working-class sailors at Spithead had been able to strong-arm the establishment. In a few short weeks, following the outbreak of the Spithead mutiny in April 1797, demands of better pay and working conditions had been met and a Royal Pardon was granted to all those involved.

Spurred on by the early successes of their fellow sailors, on 12 May 1797 mutiny was declared aboard His Majesty’s 90-gun ship, Sandwich. Within a couple of days all the vessels moored at the Great Nore were in a state of open mutiny, and after a few weeks they were also joined by other ships from Admiral Duncan’s North Sea fleet.

Once again the Admiralty found themselves threatened by common sailors, and this time they were headed by their newly appointed 'President', the Exeter-born Richard Parker. Unsurprisingly, the leader of this ‘Floating Republic’, as it was luridly dubbed by the sensationalist Courier newspaper, quickly attained considerable unpopularity within the establishment. Achieving national notoriety, it was this long-serving naval seaman who, although not one of the original organisers of the mutiny, would ultimately bear the brunt of the Admiralty’s backlash, a backlash necessitated almost entirely by the establishment’s obligation to compensate for their impotence at Spithead.

Richard Parker was the first of more than four hundred sailors court-martialed for the mutiny at the Nore and he was to become the emblematic figure of the insubordination. Thus, as a result of this notoriety, history has remembered and portrayed Parker in various contrasting ways.

The violent mutineer?

During the mutiny, the self-styled President of the ‘Floating Republic’ was rapidly vilified by loyalist newspapers of the period, typically appearing as an unstable and radical political extremist rather than as someone that the Admiralty could have plausibly negotiated with. In the Kentish Gazette, Parker was described as a ‘very desperate fellow’, accused of ‘exercising the most savage tyranny’ towards his fellow seamen. This newspaper and others of the time advocated, somewhat implausibly, that it was the fearsome influence of this one man that explained why thousands of sailors had refused to return to their duty.

As interest in the Nore Mutiny grew, newspapers also began declaring other unsubstantiated political claims about its infamous figurehead. One local news pamphlet even went so far as to state that, in the years before the mutiny, Richard Parker ‘went over to France, and was a spectator, if not an active agent, in what passed there in the time of Robespierre’.

The British press’ savage demonisation of the leader of the Nore Mutiny and his comparison with the mastermind of the French Reign of Terror not only made Richard Parker a household name but also proved invaluable to the Admiralty’s own agenda. Their depictions of Parker as a bloodthirsty revolutionary garnished both support for their new uncompromising policy towards mutiny and facilitated their eventual scapegoating of the chief mutineers. In the eyes of the establishment, Richard Parker had to represent the perfect scoundrel so that his execution could help atone for the actions of the majority - a majority who, once the mutiny ended, were pardoned and therefore allowed to return to their active duty.

The scapegoat?

The Admiralty’s need for a bogeyman figure is undeniable and typified in a letter written by the secretary of the board of the Admiralty to the president of the court at Parker’s eventual trial. In this letter Evan Nepean echoes the Admiralty’s agenda, writing about Parker that, ‘you may prove almost anything you like against him, for he has been guilty of everything that’s bad’. Throughout the mutiny, Parker’s symbolic notoriety made him the establishment’s public enemy number one. Hence, one of the many faces of Richard Parker that emerges today is that of a tyrant, who not only single-handedly maintained the mutiny but supported revolutionary ideals and had direct contact with foreign enemies.

The depiction propagated by the newspapers and the Admiralty was a gross misrepresentation of Richard Parker. Less publicised and sensationalist evidence demonstrates that his power and involvement in the mutiny were both rather limited.

Having not been involved in the initial outbreak of the mutiny, Parker was quickly elected head of the delegates of the fleet but this position was much closer to that of a representative than a despot. He was remarkably well-educated for a lower-deck sailor and thus it has been suggested that almost all the letters and interactions between the mutineers and the Admiralty were written or conducted by Parker, simply because of his literacy. If one consults his written correspondence with the Admiralty, one notices how all of his actions were typically sanctioned ‘by command of the Delegates of the fleet’ - a point that would be greatly emphasised by Parker at his eventual trial. Therefore, it is in direct opposition to the establishment’s villainous image of Richard Parker that another face emerges, one in which his role and involvement in the mutiny were purely symbolic. In this instance, Parker can be seen more as a figure of convenience, used by the more cautious and the more radical of his compatriots as a figurehead and educated mouth-piece.

The unstable husband?

This alternative perception of Parker can also be supported by the democratic decision-making that emerged aboard the mutinous ships at the Nore. As the mutiny developed committees were formed and delegates were democratically elected by all sailors to act as representatives. Indeed, a significant portion of culpability must be shifted from the shoulders of Parker on to other delegates and particularly one should consider the radical mutineers aboard Inflexible.

HMS Inflexible was widely regarded by contemporaries as the most radical and committed vessel of the fleet and it typically acted as the muscle for Sandwich’s centralised administration, a position it upheld by threatening and firing at other ships belonging to their less committed and wavering brethren. Indeed, a number of the mutineers aboard Inflexible would avoid persecution by escaping to France, further advocating for their active role in the mutiny. Richard Parker’s wife, although largely motivated by her desire to save her spouse, promoted the notion that her husband was largely unaccountable for the actions of the mutineers, even going as far as to declare that ‘at times he was in a state of insanity’.

The face of Richard Parker which emerges here could not be further from the press’s President of the ‘Floating Republic’. Instead, it rather depicts Parker as the malleable if somewhat erratic symbol of the mutiny who, despite his prominence, had little actual power or influence over the actions of the majority.

It is undeniable that there were political extremists aboard the mutinous ships at the Nore, but Parker was hardly the radical socialist tyrant that was presented by both the Admiralty and the press. This was a point he professed up until his death and even the Home Office intelligence found little proof of any connection between the mutineers and underground political societies. Parker headed mutineers who, despite their desire for substantial change to their working environment, continued to adhere to nearly all state traditions and typical naval practice.

The radical leader?

Nevertheless, Parker was hardly the educated yet unstable figurehead, innocently manipulated by radical compatriots. The elected leader of the Nore Mutiny had no hand in the mutiny’s insurrection but once he was appointed leader, he demonstrated a remarkable level of commitment to the cause of the common seaman - a degree of commitment that could have shamed many of the period’s senior statesmen. From his unusual election to his untimely death, Parker grew into his leadership role and would remain staunchly committed to the cause of his fellow seamen. Yet, in the face of the mighty British Admiralty, the unfortunate fate of the President of the ‘Floating Republic’ was sealed from the moment he assumed any position of culpability. Once the mutiny at the Nore had collapsed, in the eyes of the Admiralty and the establishment Richard Parker had to die.

Therefore, on a fateful morning aboard HMS Sandwich, Richard Parker, after having acknowledged the justice of his sentence, was reported by a member of the Admiralty to have died ‘decent and steady’. It was to be a somewhat unremarkable death for a remarkable man who, in days before, had voiced the hope that his ‘death may be considered a sufficient atonement’ for the insurrection, ‘without involving the fate of the others’. In the final hours of his life Richard Parker willingly resigned himself to his fate and thus to his officially sanctioned role as the mutiny’s repentant culprit.

Whether Parker was the socialist despot, the unfortunate scapegoat, the manipulated figurehead or the deranged husband is a question that may remain unanswered and debated amongst historians for some time. Whatever the case, the story of Richard Parker and the mutiny at the Nore is extraordinary and has certainly earned its place in history.

By Jean-Marc Hill