This online exhibition was developed as part of the An Empire of Islands workshops held at the National Maritime Museum. It examines the role of islands in the expansion and consolidation of empires.

In the early modern period – the great Age of Sail – their strategic location on or near important trade routes meant that many islands had a vital role in establishing and securing European seaborne empires. Other islands were equally as highly prized by these empires as sources of rare and valuable raw materials, or as places where profitable commodities could be cultivated. In both cases, islands frequently became sites of imperial conflict and competition.

These activities generated important collections of art, maps, objects and archives. They played (and continue to play) an important role in shaping our understanding of the relationship between islands and empires.

The following selection of objects and images reflects the themes discussed at the network’s three workshops and the expertise of individual network members. Each contributor was asked to select an object from the collection of the NMM and reflect on the way(s) in which it relates to the general themes of the network:

- islands as strategic nodes of empire;

- islands as sites of conflict and contestation;

- islands as laboratories of empire.

Many of these islands were small; some were tiny. Yet they and their collections all give us insights into how empires worked and how relationships were forged and shaped. The selection here is by no means exhaustive. However, it offers a sense of the complex relationships between islands, objects and empires that were mapped out at the network’s three workshops.

Islands of the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea

Ireland

Dublin Common Seal, 1297

In June 1229, Dublin was granted a licence to elect a mayor and at the same time created a seal of the commonality (or commune) of Dublin. Seals were visual representations of the people or institutions they were meant to signify. The images on them can tell us much about how medieval communities saw themselves. In this way, Dublin’s seal was part of the construction of the medieval city’s identity.

Dublin’s seal was two-sided: the image displayed here is the reverse of the seal. Its obverse (front) displayed a castle. This is rare, because civic seals tended to have either castles (for inland locations) or ships (coastal locations). By using both, Dublin asserted its dual identity.

The ship on the seal is a galley. It is a representation of a thirteenth-century warship, and very fitting given the strategic importance of Dublin’s fleet to the security of the English colony in Ireland. Dublin was like the Cinque Ports in England (a series of coastal towns in Sussex and Kent): it was set up to provide royal ships when needed. When this version of the seal was made in 1297, Edward I was using the fleet to aid his wars in both France and Scotland, draining Ireland of men and resources to expand his dominion abroad.

Dublin’s seal also shows the complex relationship that the city had with the wider island of Ireland. Like the ship, it was outward facing and aggressive: it supplied the English army with resources for war and expansion. Yet the obverse (front) of the seal displays a castle under siege. Crossbowmen are shown shooting from its towers, while a knight stands guard in a gateway decorated with the severed heads of Irish rebels. Medieval Dublin thus presented itself as an imperial city that defended the English colony in Ireland, and projected English power across the sea.

- Colin Veach, University of Hull

Bermuda

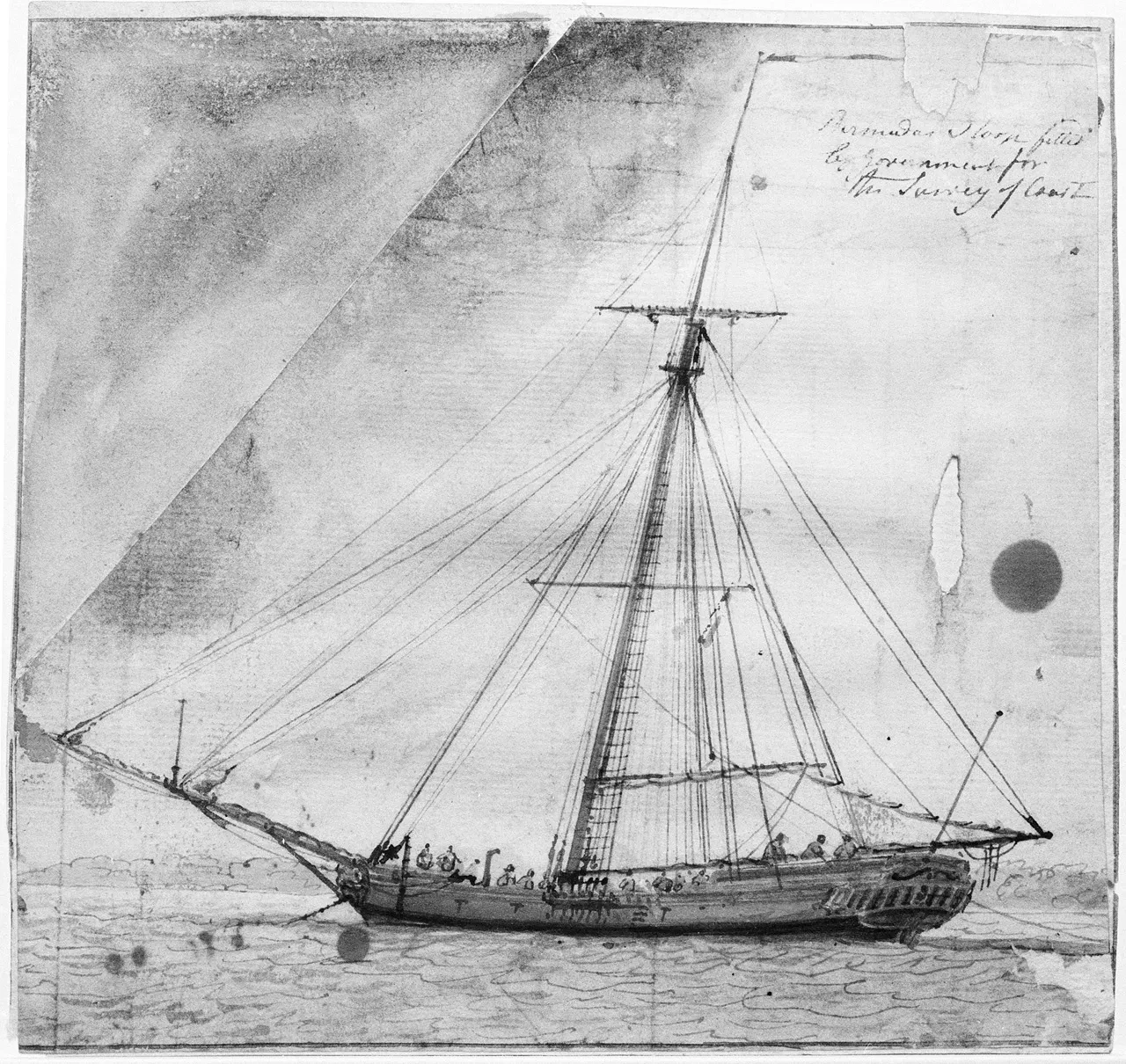

Charles Gore, ‘Bermuda sloop fitted by Government for the survey of coast’, late 18th century

Bermuda sloops were important ships in the early modern Atlantic Ocean. Designed and built in Bermuda from the mid-seventeenth century onwards, they became famous for their speed and ability to sail close to the wind.

Bermudian shipyards launched more than 5000 sloops during the eighteenth century and their design was copied by shipwrights throughout North America and the Caribbean. These vessels were favoured for their ability to outrun enemy warships. They were also often armed and fitted out as privateers.

From the 1790s, the Royal Navy commissioned more than fifty Bermudian vessels as sloops of war, serving as fast dispatch and scouting craft to support fleet operations, link dockyards, and aid in suppressing the Atlantic slave trade on the African coast. Far more numerous than square-rigged ships, sloops and schooners were the most commonly used vessels across the British Empire and in the Royal Navy, making speedy passages between ports and relaying the cargoes and news that integrated an empire of islands.

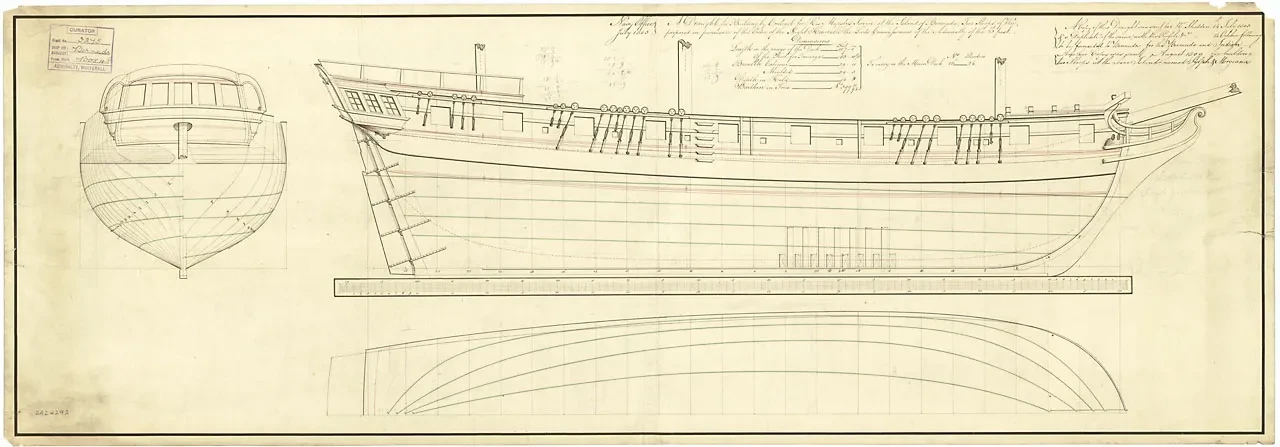

Ship plan, 1803

This ship plan documents the vessel that Royal Navy hydrographer Lieutenant Thomas Hurd used to complete his highly detailed survey of Bermuda’s coast and reefs between 1789 and 1797. Measuring approximately twelve by twenty feet (at a scale of six inches per mile) and produced at a cost of more than £12,000, it is the probably largest and most expensive chart ever produced.

Hurd’s survey was worth it. It identified channels and safe anchorages for ships of the line through the dangerous reefs that had previously prevented Bermuda being a key naval base. After the American Revolution, British America had been split into two distant halves – the Caribbean and Canada – with a thousand miles of hostile coastline in between. The island became known as ‘the Gibraltar of the West’ with an enormous naval dockyard and chain of forts to guard it. As a result, Bermuda became an especially important island in the empire which anchored Britain’s Atlantic Fleet and checked the infant United States’ aggression during the Napoleonic Era.

Although Thomas Hurd is deservedly credited for this monumental achievement, much of the actual work of taking soundings and mapping undersea reefs was done by highly skilled enslaved Bermudian pilots: ‘men of colour, very prompt and intelligent in their business’. Charles Gore’s sketch tellingly shows at least fifteen men aboard Hurd’s survey vessel, reminding us of the contributions that humble slaves and sailors – and sloops and other small sailing vessels – made in creating and sustaining an empire of islands.

- Michael Jarvis, University of Rochester

Tobago

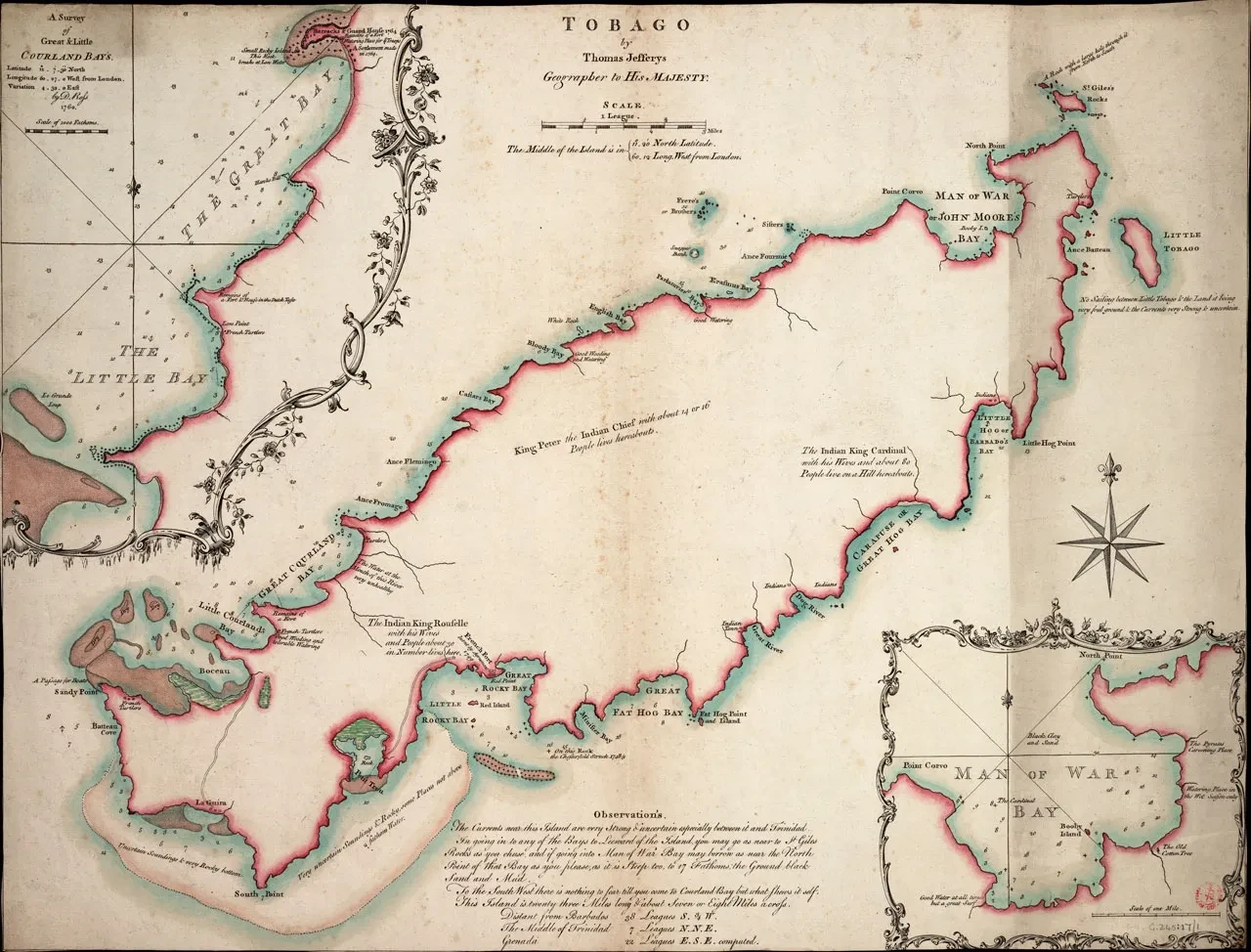

Just as islands were regarded as serving different functions around the world, so too did individual islands have different uses at different times. Maps and charts, drawn and published at different times, can convey a sense of these changing perceptions. Before the 1760s, the small Caribbean island of Tobago was officially designated as ‘neutral’ by the major European powers.

Thomas Jefferys, Tobago, c. 1770 (1760)

In the first map, drawn around 1760, the cartographer wanted to show safe anchorages for naval vessels during the Seven Years War. Much of the detail provides information about the depth of water around the coasts; the presence of rocks and currents; and places for watering and securing timber. Beyond that, the mapmaker was largely uninterested in the interior of the island, depicting it as undeveloped but, importantly, inhabited by communities of Caribs, both inland and on the coast. In total, they were believed to number around 150.

In 1763, at the end of the Seven Years War and by the Treaty of Paris, Britain acquired Tobago as a colony and quickly set about opening it up to plantation settlement. The pace of the change can be seen in the second map.

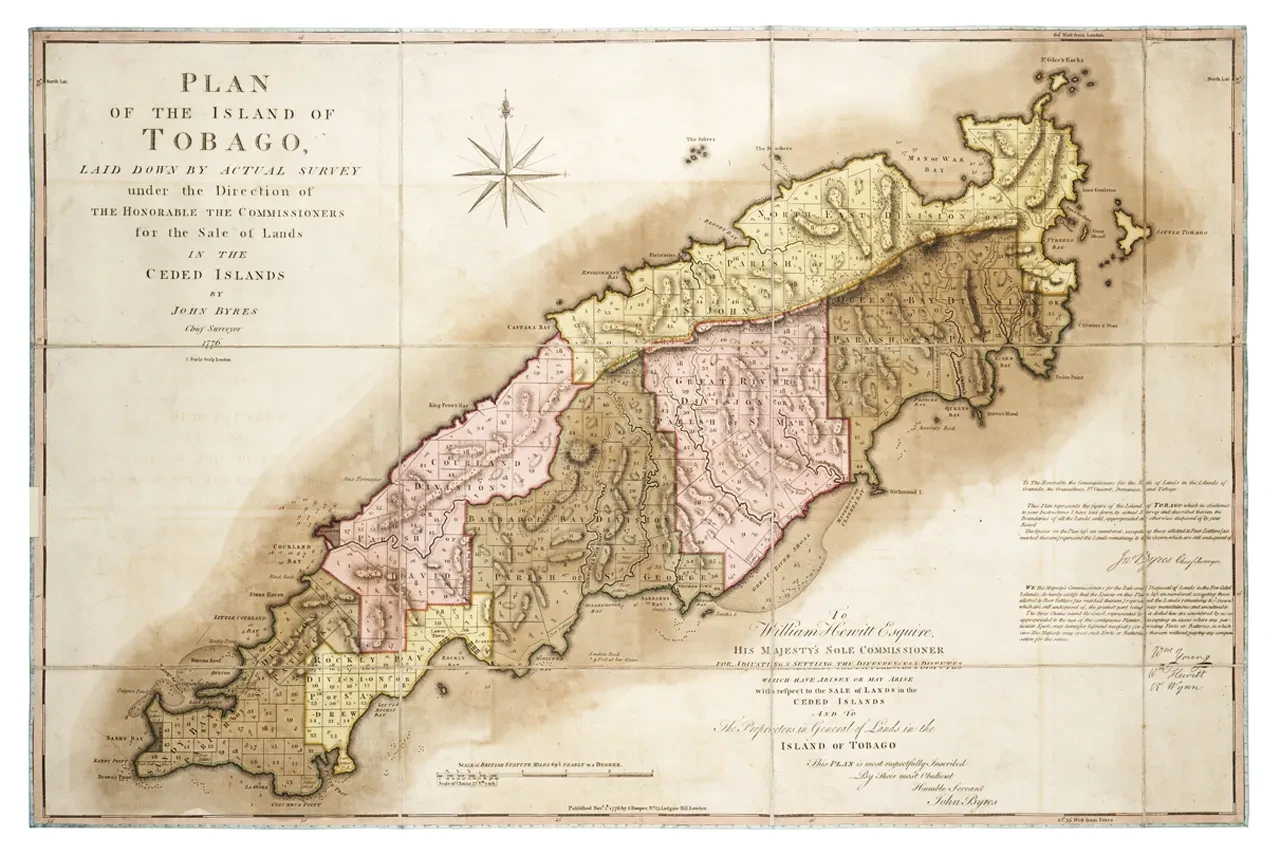

John Byres, Plan of the Island of Tobago, laid down by actual survey under the direction of the Honorable the Commissioners for the Sale of Lands in the Ceded Islands, 1776

A little of the maritime information remains, but the map now shows that the island had been sub-divided into plots of land, each one bought by (or for sale to) European settlers, including those for poor white settlers. Town settlements had been established at Scarborough; parish boundaries had been established. Forest reservations were enshrined, indicating contemporary concerns about the environmental effects of deforestation on Caribbean islands. No such concerns are apparent in relation to the Caribs, however, whose territory and way of life were simply erased by the Commissioners for the Sale of Lands, in whose name the map was drawn. The creation of plantation plots also brought a rapid and large-scale influx of enslaved Africans, on whose labour settlers were reliant.

Taken together, the charts show in microcosm the scale and pace of the transformation of Caribbean islands from tropical island Edens to powerhouses of imperial production, based on the labour of enslaved Africans.

- Douglas Hamilton, Sheffield Hallam University

Hispaniola/Haiti

Figurehead from HMS Bulldog, 1845

On the morning of 23 October 1865, HMS Bulldog, a British naval ship, opened fire on the northern coast of Haiti. After just 60 years of independence, in a country under heightened civil tension, the residents must have feared that foreign invasion was upon them. In his report, Captain Charles Wake defended his decision to bombard Cap Haïtien, which went beyond his orders: ‘it was my duty to inflict a punishment that would teach respect to the English flag and name’. He was fully supported by the national press, led by Punch magazine, which ran a cartoon featuring Wake as a bulldog and proposing three cheers: ‘May British Bull-Dogs always find Captains as stout as he’ (27 January 1866).

Recently, historians have connected the Bulldog affair with the Morant Bay uprising in Jamaica, which ignited fears of racial conflict across the post-slavery Caribbean. The two incidents, which took place within weeks of each other, were linked by conspiracy in the minds of the British colonial authorities in the West Indies, despite a lack of any tangible evidence. Their fears were undoubtedly heightened by the proximity of Jamaica and Hispaniola, the island on which Haiti was situated. The risk of revolutionary ideas and violence travelling between the two islands was a long-standing concern of the colonial authorities, highlighting the strategic vulnerability of these Caribbean islands as well as their economic and political importance.

HMS Bulldog eventually ran aground. The crew was evacuated, taking with them the ship’s figurehead, representing a full-size leaping bulldog with the words Cave Canem (Beware of the dog) inscribed on his collar. The bulldog, which to the British sailors meant courage and tenacity, would undoubtedly have had different connotations to those on shore. While slavery was gradually being abolished across the Americas, the legacy of using dogs as a method of control, intimidation and violence against black people continued. For the Haitians, the arrival of the Bulldog formed part of a century-long experience of gunboat diplomacy inflicted by global imperial powers who sought to maintain control and ‘lick [Haiti] into good behaviour’.

- Kate Hodgson, University College, Cork

Adam Callander, Shipping off Saint Helena, c. 1800

St Helena is a tiny volcanic island located near the Tropic of Capricorn in the South Atlantic Ocean. It was described in one report in 1786 as ‘the most lonely island in the universe’. Indeed, it is one of the most remote islands in the world, over 1200 miles away from the south-western coast of Africa. Today, St Helena is probably most famous for its connection with Napoleon Bonaparte, whom the British exiled to the island following his defeat at Waterloo, and who died there in 1821.

Before this, and despite its remote location, however, St Helena had long played a significant role in the East India Company’s commercial activities. By the 1680s, it was regularly referred to as ‘the Company’s Island’ and acted as a convenient convoy rendezvous on the main homeward-bound shipping route from Asia. The island also supplied passing British ships with fresh fruit, vegetables, livestock and water.

Contemporaries recognised its significance. Jacob Bosanquet, one of the East India Company’s directors, regarded the island as ‘the principal link of that chain which connects this country with her Indian possessions and of undoubted great importance’. By the early nineteenth century, Thomas Brooke, Government Secretary on St Helena, hoped ‘this little spot … may continue to protect and facilitate our commerce with the East, and, by participating in its success, be always regarded as an important and essential part of the British Empire’.

Adam Callander’s painting depicts the rocky volcanic hills of the small island crowned by the large expanse of blue sky and surrounded by the waters of the South Atlantic. The inclusion of numerous large ships at anchor off the island’s capital, Jamestown, reinforces the island’s role as an important location for British shipping. Indeed, this work may have been commissioned by the commander of an East Indiaman, or even a Royal Navy vessel, in order to commemorate the vessel’s passage to and from the waters of the South Atlantic.

- John McAleer, University of Southampton

Islands of the Indian and Pacific Oceans

Tahiti

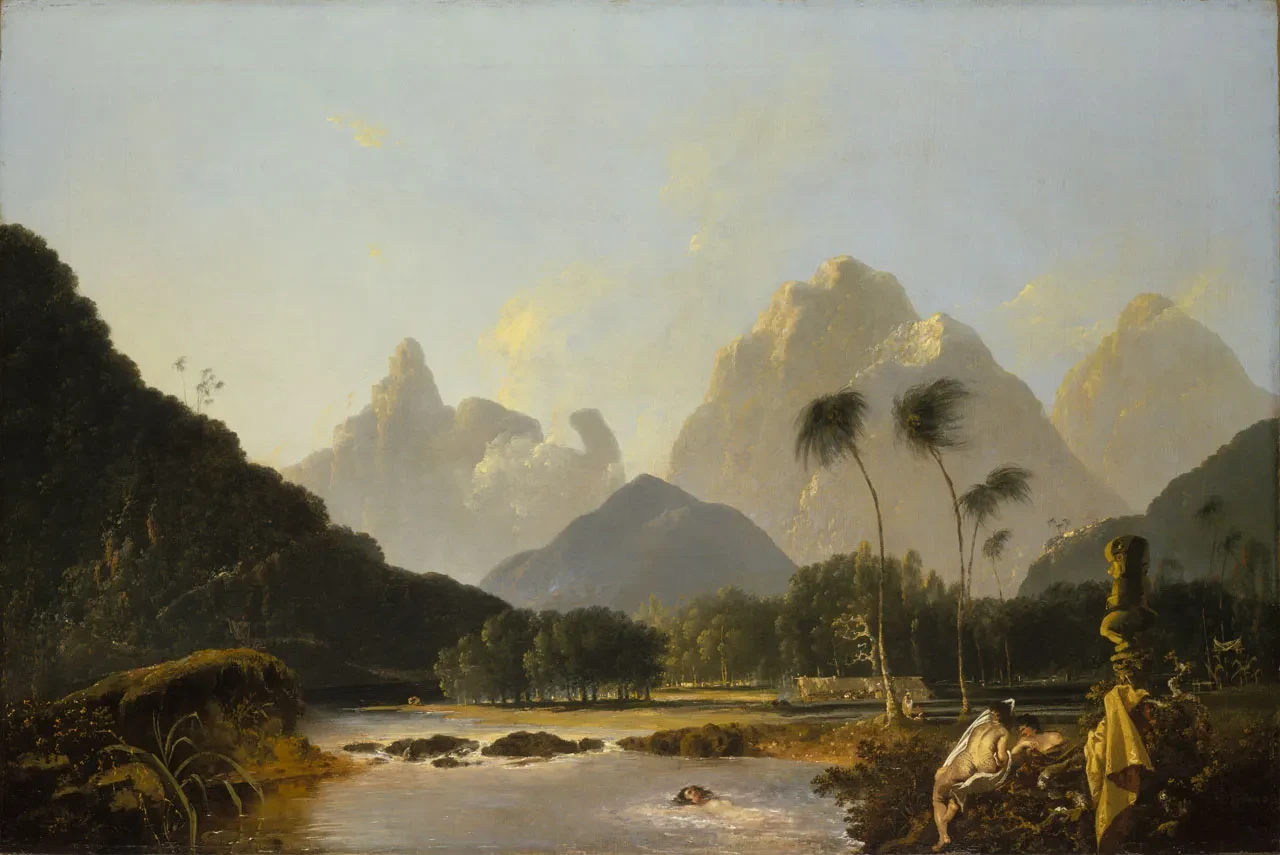

William Hodges, A View taken in the bay of Oaite Peha [Vaitepiha] Otaheite [Tahiti] (‘Tahiti Revisited’), 1776

Islands have long been represented in art and literature as idyllic spaces. The historian John Gillis has argued that ‘the Western eye had to learn to see the oceans and their islands’. Visual images – such as William Hodges’s painting of Tahiti – played a key role in this process of displaying distant islands to European audiences. Although Tahiti was never part of the formal British Empire, Hodges’s work offers an intriguing comment on the British view of this island in particular and island landscapes more generally.

William Hodges was appointed by the Admiralty to record James Cook’s second voyage to the Pacific Ocean, 1772–75. His paintings are vivid records of Pacific landscapes and societies, as well as important documents for understanding eighteenth-century British attitudes to the region and its peoples.

Hodges was a classically trained artist who used his skills to capture the island’s exquisite landscape. Tahiti Revisited depicts the beauty and peace of Vaitepiha Bay. The inclusion of several female figures bathing in the river transforms the landscape into an idyllic paradise with erotic charms. The statue or tii, which stands over the figures in the right foreground as they prepare to bathe, further reinforces the notion of the exotic. Hodges presented an image of Tahitian society seemingly untouched by European contact, since the image includes no hint of Cook’s party. However, the shrouded body on the far right implies that even in such a tropical idyll, death is present. Hodges used this personal interpretation of Tahiti to reveal the island’s beauty and to hint at its temptations. His paintings helped to create a vision of a ‘typical’ tropical island that has proved remarkably durable.

- John McAleer, University of Southampton

Kerguelen Islands

Wall-mounted astronomical regulator by E. Dent & Co, no. 2010, c. 1870

Islands have long been important in the expansion of scientific knowledge as ‘laboratories’ in which to make observations. They acted as sites of scientific research throughout the imperial era. Commissioned by Astronomer Royal, George Airy, this astronomical regulator was one of nine designed for observing the 1874 Transit of Venus. A regulator is essentially a very precise clock and is particularly useful for making observations in tandem with telescopes or other instruments. Roughly once every century, Venus makes two transits eight years apart, which can be measured to establish the distance of the Earth from the Sun. The 1874 and subsequent 1882 transit represented ‘a grand astronomical jubilee’ according to the newspaper, The Graphic, of 27 June 1874.

This regulator and other instruments necessary for taking measurements of the Transit were dispatched to one of the British temporary observatories from which the event was to be observed (Hawaii, Rodrigues, Christchurch, Cairo and the Kerguelen Islands). The distance between the sites was crucial. The Astronomer Royal wanted them to be ‘as far asunder as possible’, as The Graphic reported, but as they had to be based on land, far-flung islands in the centre of vast oceans, such as Hawaii and the Kerguelens in the southern Indian Ocean, were ideal locations.

The Kerguelen Islands were bleak and cold, named ‘Desolation Islands’ by Captain Cook. They were home only to occasional scientific expeditions and numerous seabirds including penguins and mollyhawks. The men sent there encountered by far the most hostile environment and remote setting of all the teams observing the Transit. The need to take precise measurements, represented by this astronomical regulator, governed the lives of those sent to these isolated locations. The journals of Royal Naval Officer, A. H. Smith-Dorrien, also present in the National Maritime Museum’s collection (SMD/1–7), record his experiences of observing the Transit as the ship’s quartermaster, and vividly capture the challenge of living in such an isolated and desolate environment in the service of science and empire.

- Sarah Longair, University of Lincoln

Mauritius

Medal awarded for the capture of Rodigues, Isle of Bourbon, and Isle of France, 1809–10

This medal was awarded to a sepoy, or Indian soldier, for his role in capturing three strategically important French islands at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Located at the south-western gateway to the Indian Ocean, these islands were crucial for French commercial and colonial ambitions in Asia. The Ile de France (present-day Mauritius) was long regarded as the ‘star and the key of the Indian Ocean’. In 1798, an American trader, Martin Bickham, explained that ‘the situation of this island is so convenient for trade, and its port so commodious that there will be doubtless a great deal of good business done here. It can be looked upon … as the store house of the eastern world’.

For the British, and the East India Company in particular, any potential commercial advantages to be derived from these islands were threatened by the danger posed by the French presence there. Their location, on a key shipping route between Asia and Europe, gave any enemy based there the potential to inflict severe damage on British maritime and trading activities. Henry Keating, a British soldier involved in their capture, described the islands as ‘citadels of French power in the East’. Matters came to a head during the war against Napoleonic France, and an expedition was sent to capture the three islands in 1809. Lord Minto, the Governor-General in India, regarded the taking of Ile de France the following year as one of the most important services ‘that could be rendered to the East India Company and the nation in the east’.

The East India Company employed tens of thousands of Indians in its navy and armies. Without them, it could not have become an important military power in Asia. This medal shows the extent to which the British presence in India had ramifications for the wider Indian Ocean region. It also demonstrates the crucial role of distant islands in consolidating the British commercial and political presence in Asia.

- John McAleer, University of Southampton

Penang

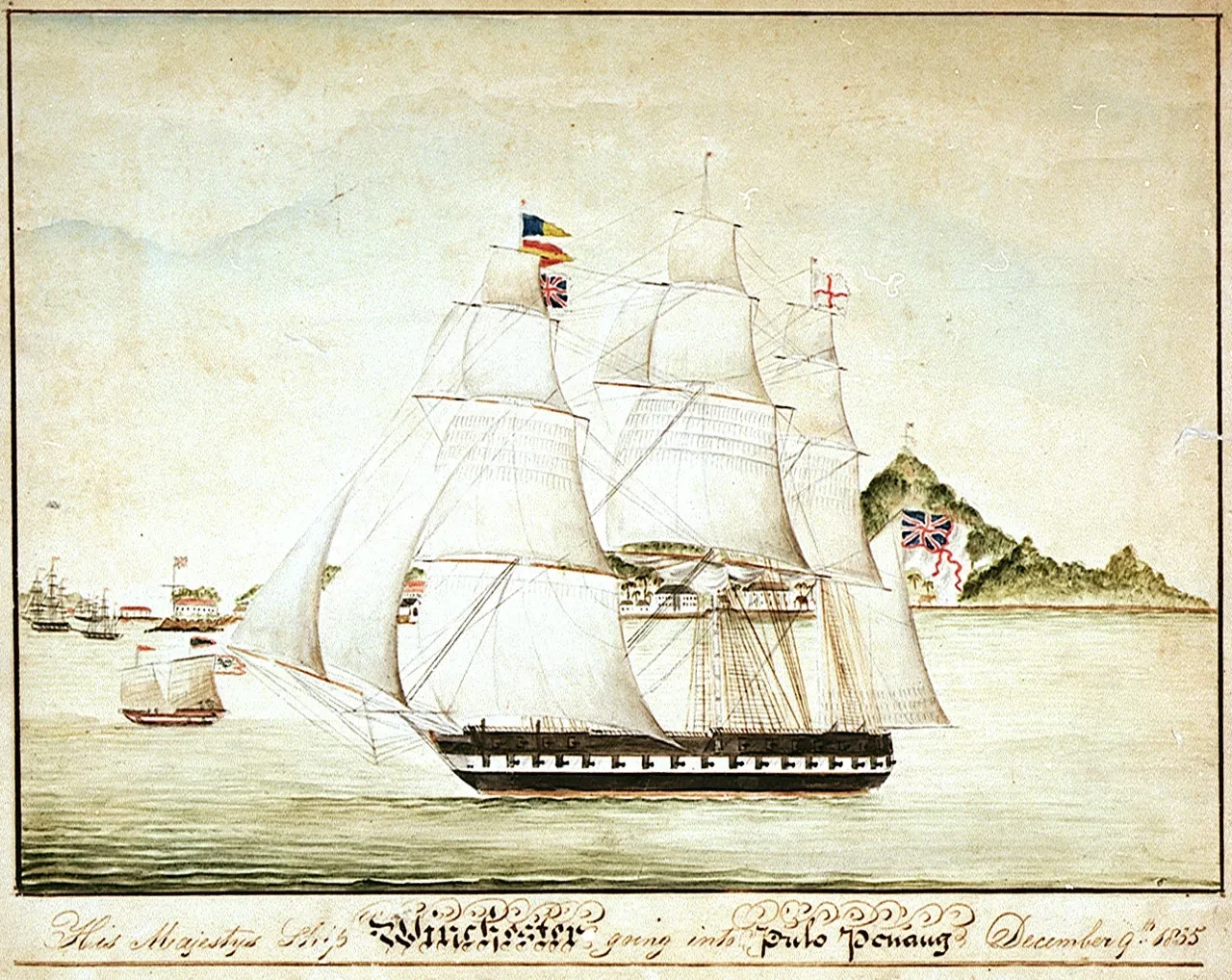

‘His Majestys Ship Winchester going into Pulo Penang’, c. 1835

The island of Penang – also known as Prince of Wales Island, and now part of Malaysia – is located near the Strait of Malacca, which connects the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea. Its strategic situation was a key consideration when Francis Light established a trading entrepôt there in 1786, and the islands became an important part of the East India Company’s ‘country trade’. This lucrative operation involved Company ships carrying goods between ports in Asia instead of back to London. The Company’s trading ‘factories’ were scattered around the Indian coast, on the eastern shores of the Bay of Bengal, and in China. Country-trading ships carried cargo such as cotton, betel nut, spices, and opium, which were exchanged for precious specie (currency). The Company made vast profits, as did ships’ captains who reaped the benefits of private trade, or ‘indulgence’.

The island also served other purposes for the East India Company and its administration in India when it became the Company’s first overseas penal settlement. Between 1789 and 1860, it received around 6000 convicts transported from India. When the Company lost the last of its trading monopolies in 1834, private ship owners could tender for the transport of these convicts, making this another means for profiteering.

The convicts were highly valued in the penal settlements themselves. In Penang, as in other Company territories, they built the infrastructure necessary for the expansion of trade. This included roads and the construction of the channel and pipes necessary to supply George Town, the capital, with water. The convicts carried on their own form of private trade too, using the stems of six-foot-tall palms to construct walking sticks. They gave these the humorous name ‘Penang Lawyers’, and either sold or exported them.

The vessel depicted here, HMS Winchester, served as the flagship on the Royal Navy’s East Indies and China Station. The image of the 60-gun frigate against the backdrop of the shoreline emphasises the importance of island bases like Penang to British activities – both commercial and military – in the Indian Ocean world.

- Clare Anderson, University of Leicester

Australian Islands

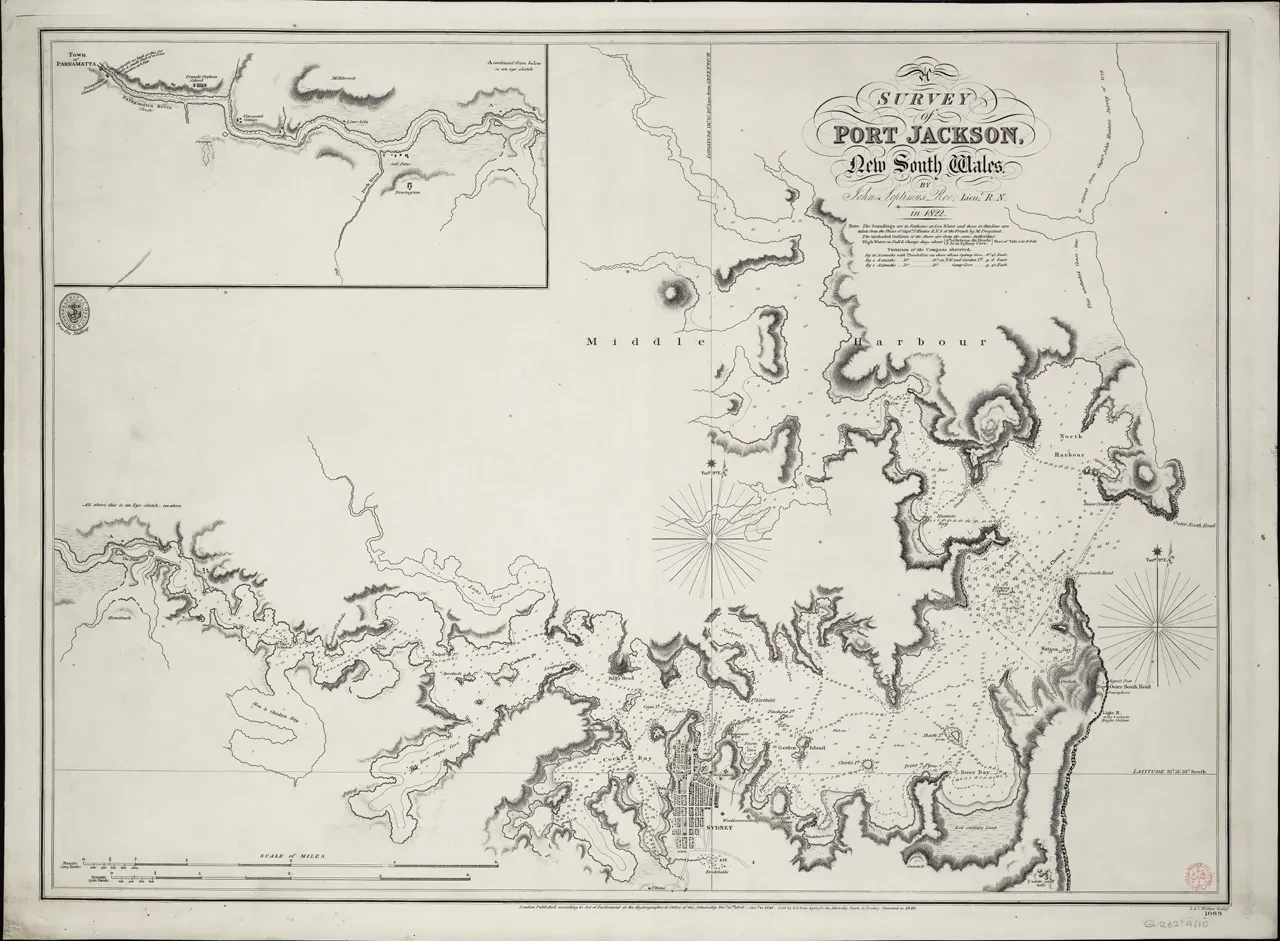

Septimus Roe, A survey of Port Jackson, New South Wales, 1822

This survey of Port Jackson in New South Wales was drawn by the mapmaker John Septimus Roe in 1822. Three of the fourteen islands in Sydney Harbour were used to exile convicts as a punishment. Here, the convicts were put to work, and their labour helped to expand Britain’s empire in Australia.

Just three weeks after the First Fleet arrived in 1788 carrying convicts-turned-colonists to Australia, Thomas Hill was marooned on a small rocky island in Port Jackson for stealing. The island continued to be used to exile convicts until the early 1800s. Because convicts were given only starvation rations, the island became known as ‘Pinchgut Island’.

From 1833, gangs of convicts quarried Goat Island (Me-mel) to build an arms magazine, and in 1841 convicts levelled Pinchgut Island (Mat-te-wan-ye) to defend against foreign attack. Between 1839 and 1869, convicts who had re-offended were instead sent to Cockatoo Island (Wa-rea-mah) in the harbour, where they built what was intended to be the largest dry dock in the southern hemisphere.

The work of convicts on islands was important for the development of Sydney into a global city.

The creator of this map, John Septimus Roe (1797–1878) encountered many more prison islands on his travels. This included Melville Island at the northernmost edge of Australia and Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) in Western Australia. Roe was credited with formally marking possession of Melville Island on 20 September 1824 by burying documents which stated Britain’s claim to the land. On Rottnest Island, he encountered the Indigenous ‘Nyoongar’ men imprisoned there, when he chose the site for the colony’s first lighthouse in 1841.

While men like Roe are credited with ‘surveying’ and creating new knowledge for Europeans about these islands, it was European and indigenous prisoners – often omitted in official histories – who actually built the infrastructure the colony needed.

- Katy Roscoe, University of Liverpool