Take a closer look at the hairy diary of a sailor involved in one of the search expeditions to find Sir John Franklin and his crew.

In 1845, an expedition led by Sir John Franklin entered the Arctic in an attempt to locate a Northwest Passage. The entire expedition then vanished.

Multiple search parties followed, trying to find Franklin and his crew, or at least understand what happened to them. (It is now known that it was scurvy, starvation, and cannibalism.)

This blog post looks at the diary of a sailor who took part in one of these search expeditions, which holds its own smaller mystery—why is it hairy?

Brett and HMS Investigator

The diary (JOD/282) belonged to William Brett, who took part in Sir James Clark Ross and Edward Joseph Bird’s search for Franklin in HMS Enterprise and HMS Investigator, beginning in 1848. According to Investigator’s muster roll, transcribed on Arctonauts, a collection of online sources on polar exploration, Brett was 28 when he joined the ship. He was first quartermaster and then captain of the forecastle on board Investigator.

He writes in his diary that he volunteered ‘with the intention of joining one of H M Ships fitting out at Woolwich on a Voyage of Discovery in search of Sir John Franklin.’

The content of Brett’s diary is interesting in its own right, especially when compared to formal, published accounts of the same expedition, like these official reports.

Brett complains about the Blackwall Yard cutting corners (‘That is Blackwalling of it’), notes how enthusiastically the illiterate members of the ships’ crews attended the classes he taught, and describes how while the ships were frozen in the Arctic, ‘some hands played a game of rounders on the ice.’

Getting hairy?

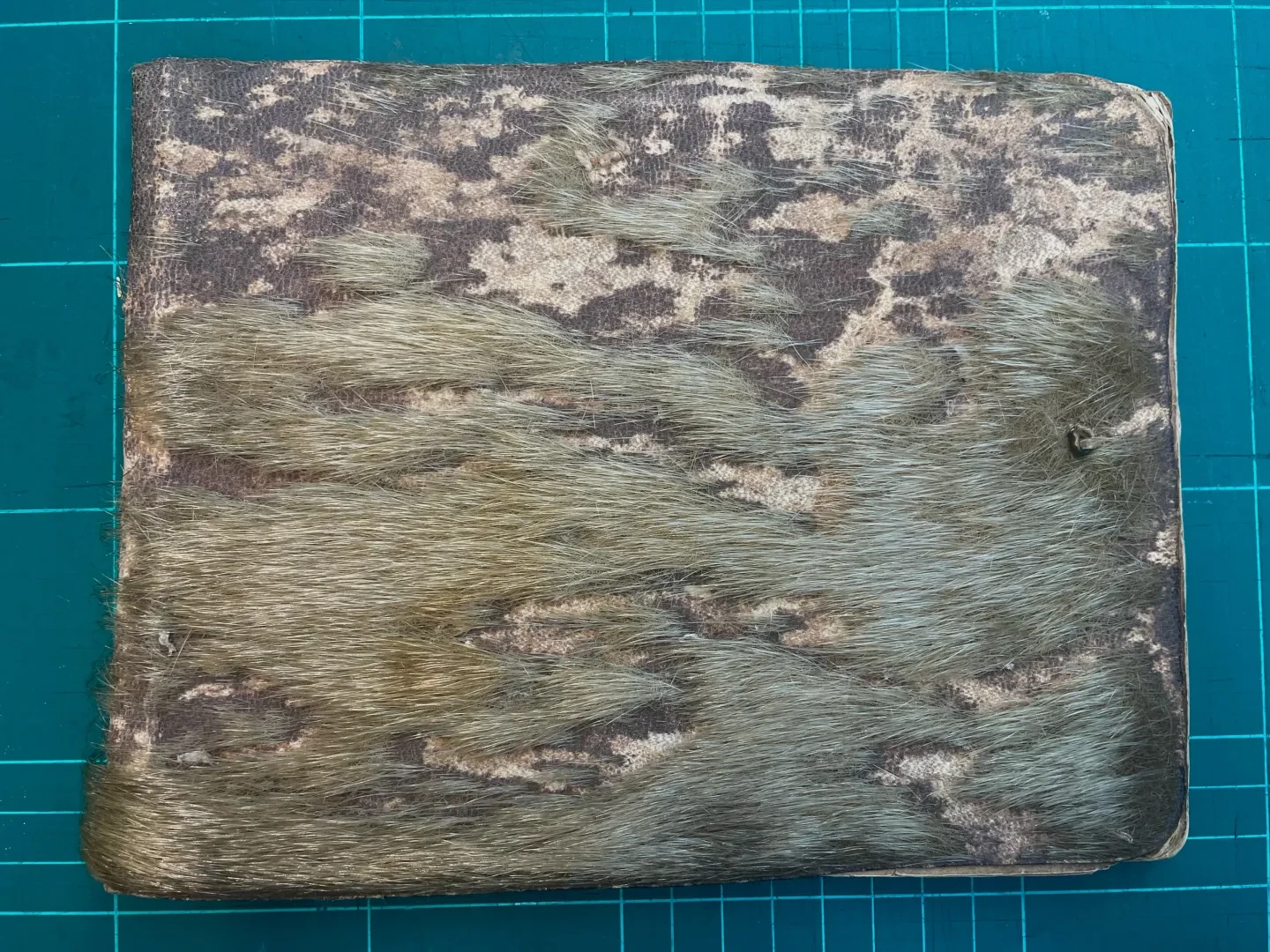

But the ‘hairy’ cover of the diary is what makes it stand out—as far as Library and Archive staff are aware, it is the only such cover we have. But what animal did this hairy cover come from?

There are examples of mediaeval manuscripts with similar covers (often referred to as ‘libri pilosi’, which is Latin for ‘hairy books’) that have been bound in cowhide or calfskin. There is also the recent discovery of a large number of twelfth and thirteenth century French manuscripts being bound in sealskin—with the hair still attached!

The covers of these hairy books (as well as other sealskin examples) look very similar to our example. And the hair on Brett’s diary is the right length, and the pattern resembles the patterns on the coat of a seal... Could Brett’s diary be bound in sealskin?

Sealskin would be a practical choice for a book cover in the Arctic, as it is waterproof. And Brett had plenty of opportunities to get hold of it. In his diary he mentions several occasions when he either observed or participated in hunting parties to shoot seals and other animals, and on November 21st, 1848, he writes that he ‘presented the ship’s company with [...] 1 pair of sealskin gloves.’ Using the same material to house his diary was something Brett was very capable of.

‘Tusks ¾ inches, talons 2 ½ inches, hair 9 inches’

More intriguing is the suggestion that the cover could be polar bear fur. Alongside Brett’s diary is a letter from William Herbert Ifould, who as librarian of the State Library of New South Wales turned down a previous owner of the diary’s offer to donate it. Ifould comments that it is ‘a relic which collections of special things like these might desire to have, especially as it has been bound in Polar Bear skin.’ Could this be the answer?

Brett’s diary entry for August 8th, 1848, reads: ‘Saw a large white bear. Lowered a boat and went after him with success.’ Brett then lists the bear’s measurements after they brought it on board, including ‘tusks 1 ¾ inches, talons 2 ½ inches, hair 9 inches.’

Across August and September 1848, Enterprise and Investigator caught at least six polar bears. But as Brett describes, polar bear fur is very long, and the hair on the diary is an inch at most. The diary also has a mottled pattern, while polar bear skin is uniform and black, to help keep them warm. So, although polar bear skin would be a good story, it can probably be ruled out.

Using foxes to find Franklin

Another possible (if unlikely) option is that the hair came from an Arctic fox. Brett records that the crew of Enterprise caught their first fox on October 2nd, 1848. This was followed by several more, until on November 13th, ‘there being a quantity of foxes to be caught, the Commodore [Ross] came to the determination of making an heroical use of them and this morning sent one away after fixing a collar’ engraved with the names of the ships, their captains, and their latitude and longitude. The hope was that if Franklin or his crew found one of the foxes, this message would guide them to the search party.

Enterprise and Investigator continued to trap foxes and release them with these collars, as did subsequent search expeditions, as this article in Polar Record explains. But like polar bears, Arctic foxes have fur that is too long and uniform in colour to be a good match for the cover of Brett’s diary.

The mystery remains...

Based on the book’s physical characteristics and the availability of materials Brett would have had access to, I believe that the diary cover is sealskin. I have done my best to carefully compare the cover of our ‘hairy book’ to reference images of different types of fur on the Alaska Fur Identification Project website, book covers known to be sealskin, various badly taxidermied polar bears, and this sealskin purse in the museum’s object collection—which is what ultimately convinced me. It is from around the same time period as Brett’s diary, and the skin is almost identical. But unfortunately, without a good microscope and more expertise than I have, confirmation of the nature of Brett’s diary cover will have to remain—like the fate of Franklin—a mystery.

Further reading

William Brett. Diary of William Brett on HMS INVESTIGATOR search for Franklin's expedition and party, 1848. JOD/282.

W.H. Browne. Ten coloured views taken during the Arctic expedition of Her Majesty's ships Enterprise and Investigator under the command of Captain Sir James C Ross. London, 1850. PBD3130.

R.M. Peck. 'Collaring nature: The use of foxes to find and rescue the members of the lost Franklin expedition,' in Polar Record (2024; Vol. 60, e5).