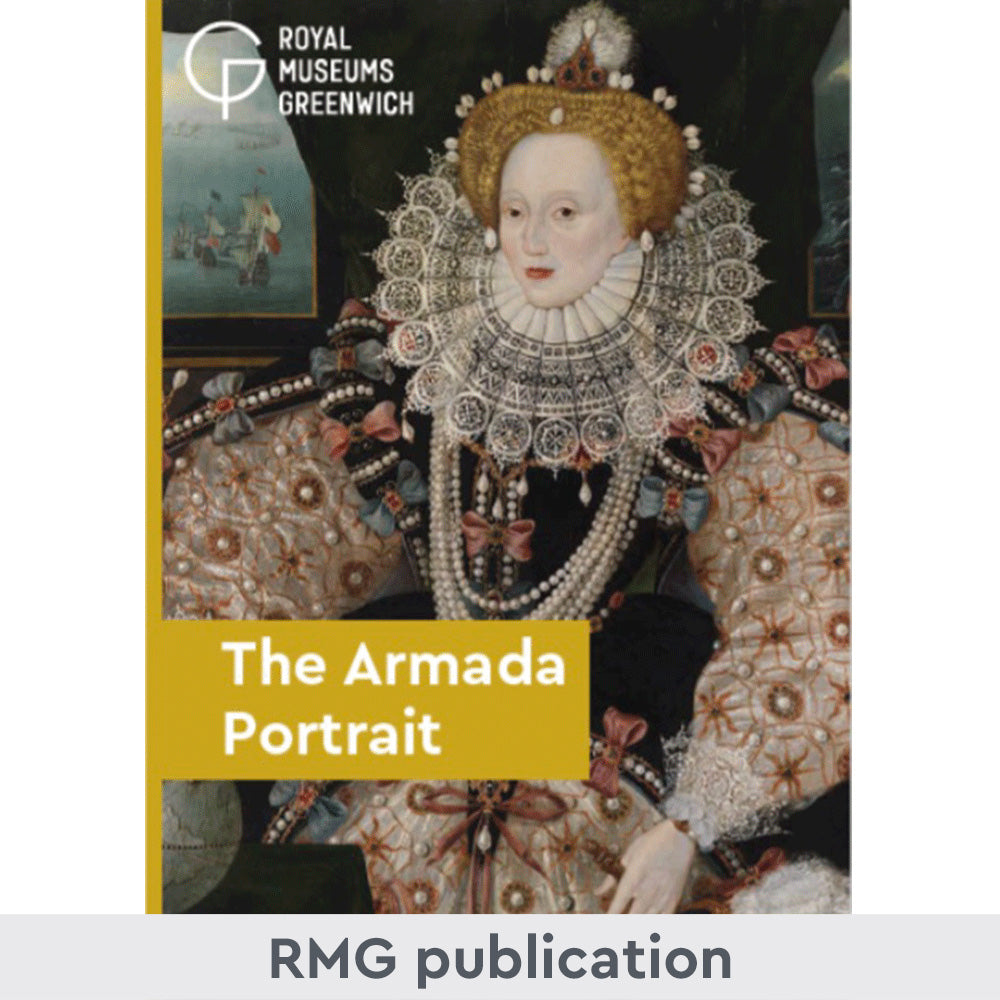

The Spanish Armada was the defining moment of Elizabeth I's reign. Spain's defeat secured Protestant rule in England, and launched Elizabeth onto the global stage.

History of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada was one part of a planned invasion of England by King Philip II of Spain.

Launched in 1588, ‘la felicissima armada’, or ‘the most fortunate fleet’, was made up of roughly 150 ships and 18,000 men. At the time, it was the largest fleet ever seen in Europe and Philip II of Spain considered it invincible.

What happened?

Why did the Spanish Armada happen?

Years of religious and political differences led up to the conflict between Catholic Spain and Protestant England.

The Spanish saw England as a competitor in trade and expansion in the ‘New World’ of the Americas.

Spain's empire was coveted by the English, leading to numerous skirmishes between English pirates and privateers and Spanish vessels. English sailors deliberately targeted Spanish shipping around Europe and the Atlantic. This included Sir Francis Drake's burning of over 20 Spanish ships in the port of Cadiz in April 1587.

Meanwhile, Walter Raleigh had twice tried - unsuccessfully - to establish an English colony in North America.

Plans for invasion accelerated however in 1587.

The turning point came following the execution of Mary Queen of Scots – Spain’s Catholic ally. The killing of Mary Queen of Scots, ordered by Elizabeth, was the final straw for Philip II in the religious tensions between the two countries.

How did the campaign begin?

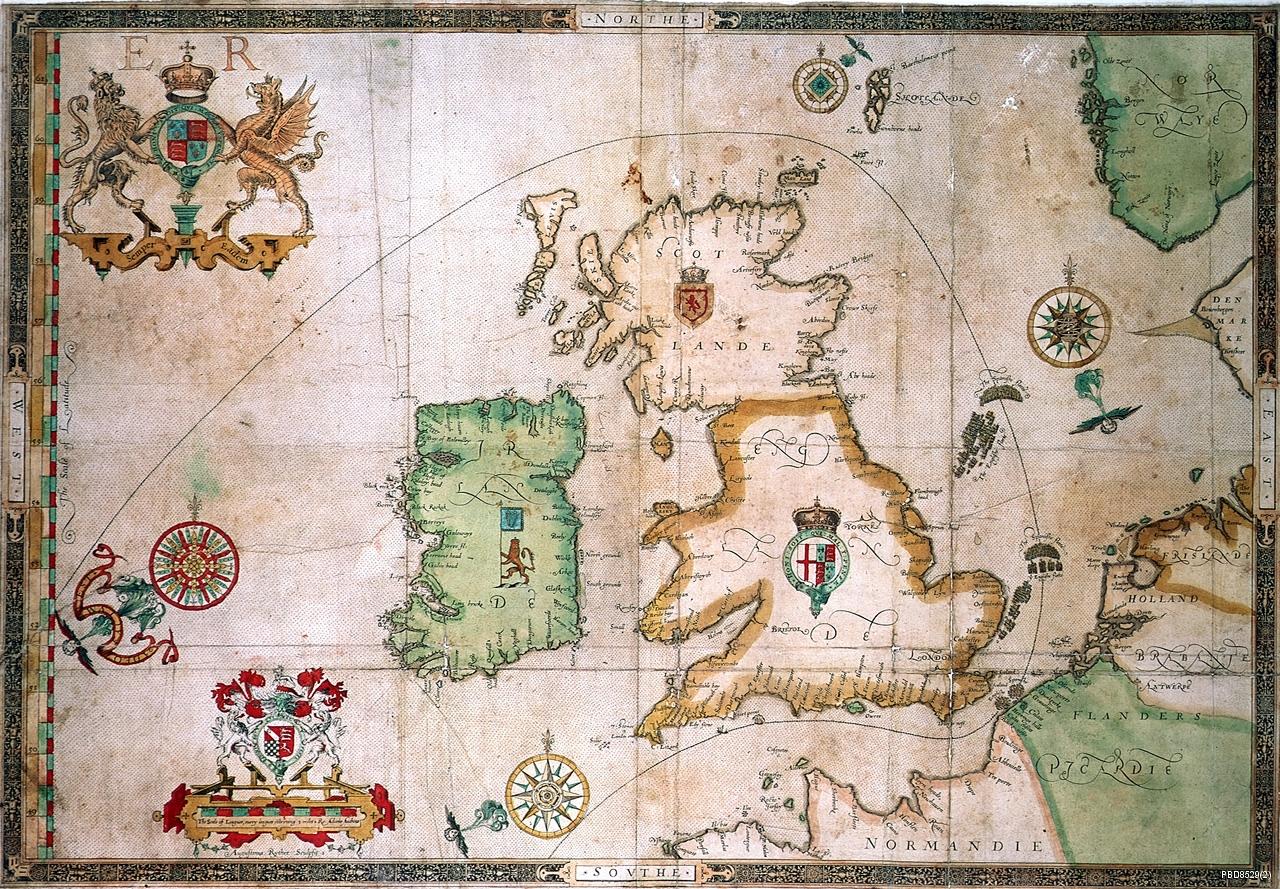

In 1588, Philip II intended to sail with his navy and army, a total of around 30,000 men, up the English Channel to link up with the forces led by the Duke of Parma in the Spanish Netherlands. From there they would invade England, bring the country under Catholic rule, and secure Spain's position as the superpower of Western Europe.

Beacons were lit as soon as the Armada was sighted off the English coast, informing London and Elizabeth of the imminent invasion.

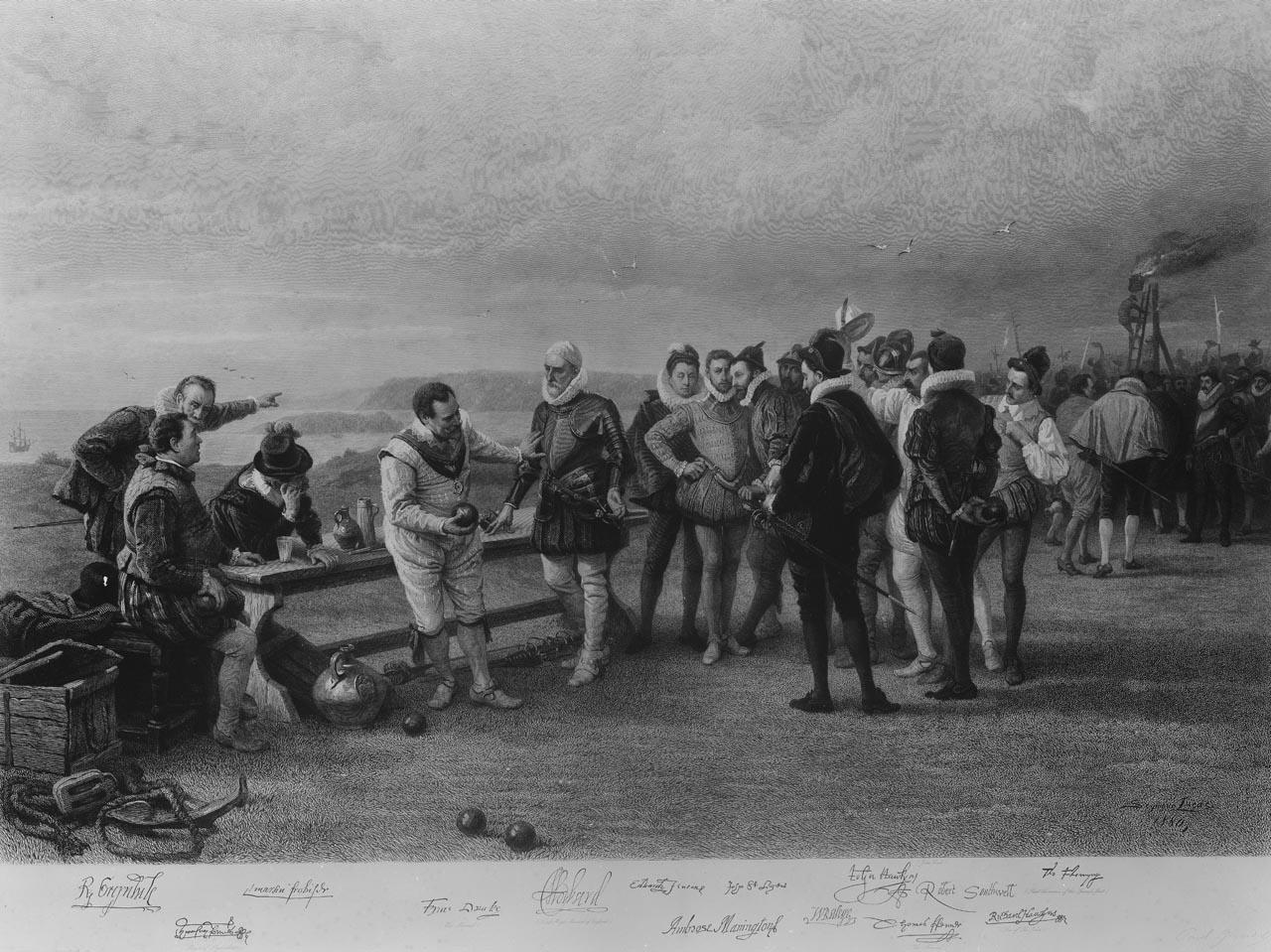

According to legend, Francis Drake was first told of the sighting of the Armada while playing bowls on Plymouth Hoe. He is said to have answered that ‘there is plenty of time to finish the game and beat the Spaniards’ - but there is no reliable evidence for this.

The English ships were longer, lower and faster than their Spanish rivals. The decks fore and aft had been lowered to give greater stability, and this meant more guns could be carried to fire lethal broadsides. The ships were also more manoueverable than the heavy Spanish vessels.

Visit the Queen's House

What happened when the Armada attacked?

The commander of the Armada was the Duke of Medina Sidonia. The Duke had set out on the enterprise with some reluctance, as he was wary of the abilities of the English ships. However, he hoped he would be able to join with the forces of the Duke of Parma in the Netherlands, and find safe, deep anchorage for his fleet before the invasion of England. To his dismay this did not happen.

The Spaniards maintained a strict crescent formation up the Channel, which the English realised would be very difficult to break.

Despite this, two great Spanish ships were accidentally put out of action during the initial battles. The Rosario collided with another ship, was disabled and captured by Drake, while the San Salvador blew up with tremendous loss of life.

The two fleets skirted round each other up the Channel with neither gaining advantage.

How did English fireships help break the Spanish Armada?

On 27 July 1588, after the Armada had anchored off Calais, the English decided to send in eight 'fireships'.

These were vessels packed with flammable material, deliberately set alight and left to drift towards enemy ships.

At midnight, the fireships approached the Spanish Armada. The Spanish cut their anchor cables ready for flight, but in the darkness many ships collided with each other. While none of the Spanish ships were set on fire, the Armada was left scattered and disorganised.

Next morning, there was the fiercest fighting of the whole Armada campaign during the Battle of Gravelines. By evening, the wind was strong and the Spanish expected a further attack at dawn, but as both sides were out of ammunition none came.

That afternoon the wind changed and the Spanish ships were blown off the sandbanks towards the North Sea. With no support from the Duke of Parma and their anchorage lost, Medina Sidonia's main aim was to bring the remains of the Armada back to Spain.

Why did the Spanish Armada fail?

Many ships were wrecked off the rocky coasts of Scotland and Ireland. Of the 150 ships that set out, only 65 returned to Lisbon. The following year, Philip sent another smaller fleet of about 100 ships. This too ran into stormy weather off Cornwall and was blown back to Spain.

It was not until the reign of James I (ruler of Scotland and England 1603–1625) that peace was finally made between the two countries.

Spanish Armada timeline: 1588

12 July: The Spanish Armada sets sail

18 July: The English fleet leaves Plymouth but the south-west wind prevents them from reaching Spain

19 July: The Spanish Armada is sighted off the Lizard in Cornwall, where they stop to get supplies

21 July: The outnumbered English navy begins bombarding the seven-mile-long line of Spanish ships from a safe distance, using the advantage of their superior long-range guns

22 July: The English fleet is forced back to port due to the wind

22 - 23 July: The Armada is pursued up the Channel by Lord Howard of Effingham’s fleet. Howard was the commander of the English forces, with Francis Drake second in command. The Spaniards reach Portland Bill, where they gain the weather advantage, meaning they are able to turn and attack the pursuing English ships

27 July: The Armada anchors off Calais to wait for their troops to arrive. The English send in fireships that night

28 July: The English attack the Spanish fleet near Gravelines

29 July: The Armada is re-joined by the rest of the missing ships

30 July: The Armada is put into battle order

31 July: The Spanish fleet tries to turn around to join up with the Spanish land forces again. However, the prevailing south-west winds prevent them from doing so

1 August: The Armada finds itself off Berry Head with the English fleet far behind. Howard is forced to wait for his ships to re-join him

2 August: The Armada is located to the north of the English, near Portland Bill. Both fleets turn east

6 August: Both fleets are once again close but avoid any conflict

9 August: After the main danger is over, Elizabeth travels to speak to the English troops at Tilbury

12 August: The fleets come close again, with the Armada in good shape. However, still no fighting takes place, and the Spanish ships are ordered to sail north. Stormy weather plagues them for the rest of the voyage

1 September: the ship Barca de Amburgo sinks in a storm near Fair Isle, Scotland

3 September: the Duke Of Medina Sidonia, commander of the Armada, sends a message Philip II that there have been four nights of storms, and 17 ships have disappeared

12 September: The ship Trinidad Valencera is caught in a bad storm, and is eventually forced to land near Kinnagoe Bay in Ireland

October: The remaining Armada ships manage to return home. safety in the north and many lives were spared.

Main image: English ships and the Spanish Armada, August 1588 (BHC0262, © NMM)