Who was Isambard Kingdom Brunel?

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859) was a renowned 19th century engineer. His achievements include the steamships Great Western, Great Britain and Great Eastern.

Who was Isambard Kingdom Brunel?

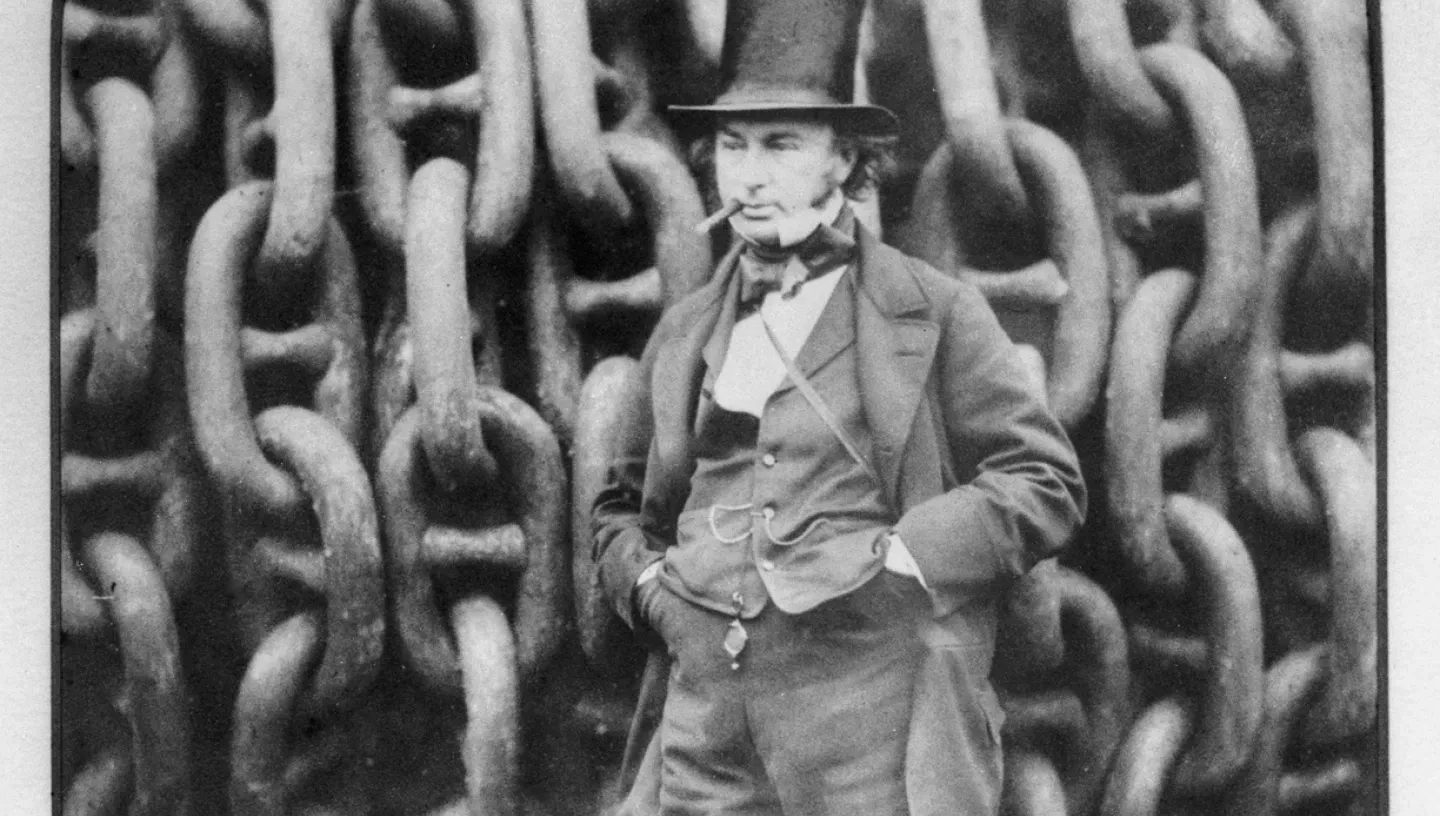

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806 - 1859) was one of the most famous civil engineers and mechanics in history. In a 2002 poll by the BBC, Brunel was voted the second greatest Briton of all time (after Winston Churchill). Brunel’s feats and achievements have had a lasting legacy and revolutionised how we approach engineering, transport and construction.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel facts

Who were Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s parents?

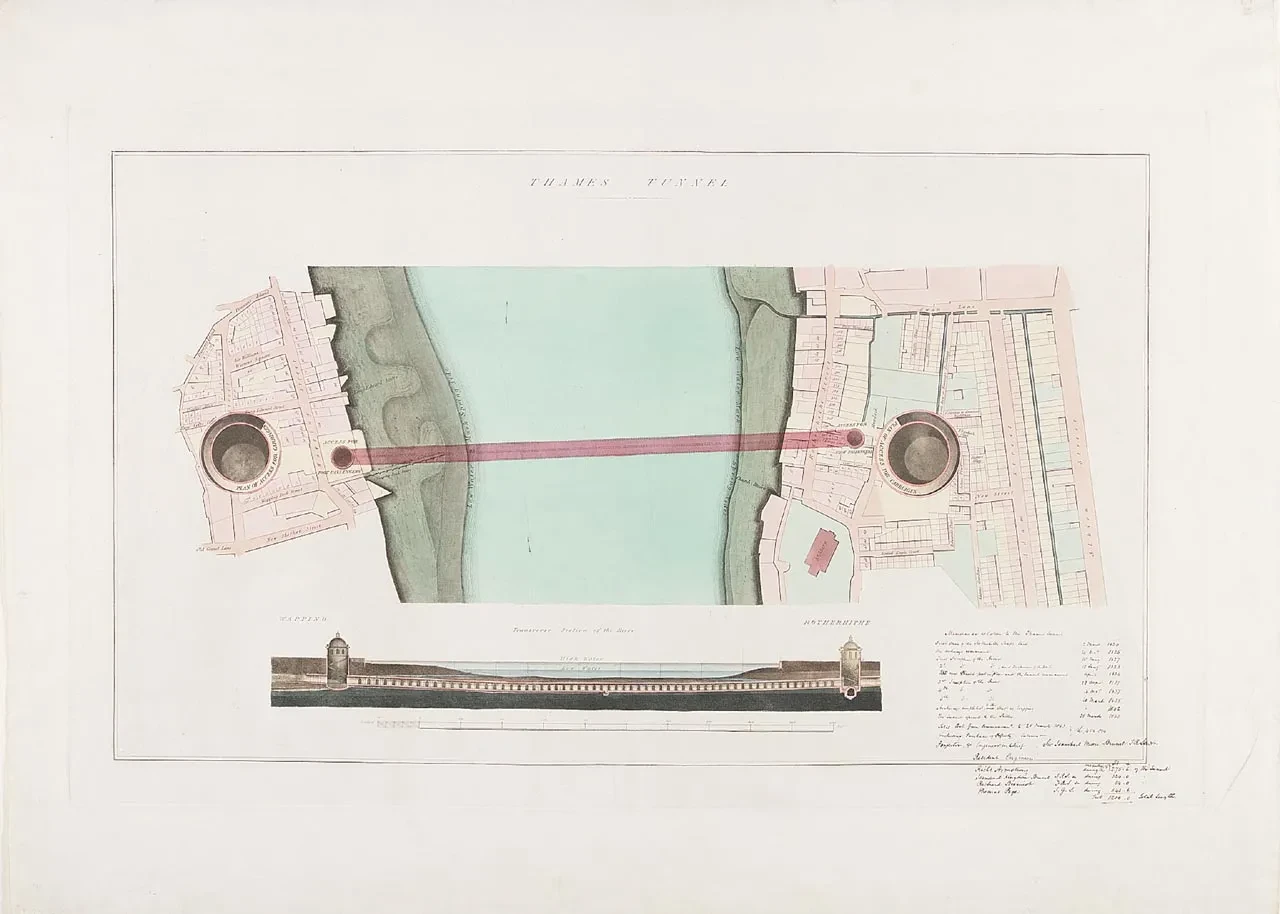

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was the son of the famous inventor, Sir Marc Isambard Brunel and Sophia Kingdom. Similar to his son, the scope of Marc’s designs were remarkable. Marc invented new methods for the mass production of ships’ pulleys and soldiers boots to his designs. His most famous achievement was his pioneering work in the design and construction of the Thames Tunnel. Prince Albert took a keen interest in the project, and it was this project that led to Marc's knighthood.

Sophia Kingdom & the French revolution

Marc and Sophia first met in Paris during the French Revolution. As a known royalist, Marc had to flee France for New York. Sophia remained in Paris to finish her studies and was charged with being a British spy. She remained in prison until the end of the revolution. They found each other again in England and married in 1799 with Sophia giving birth to Isambard Kingdom Brunel in 1806.

Brunel - a child genius?

From a young age, Isambard had a talent for engineering and mathematics. Encouraged by his father, he learnt how to depict model drawings of buildings and had begun learning Euclidean geometry by the age of eight. After being educated in Hove and Caen, Isambard was sent to France to apprentice under Louis Breguet, France’s most celebrated maker of watches and scientific instruments.

What did Isambard Kingdom Brunel invent?

Rotherhithe Tunnel

By the age of 20, Isambard had begun working with his father on the ground-breaking Thames Tunnel between Rotherhithe and Wapping. This 1300 foot tunnel used a groundbreaking tunnel shield design developed by Marc and Isambard. Using this system, they were able to protect workers from the dangers of tunnel collapse as they buried under 75 feet under the river. The Rotherhithe tunnel is still in use today.

Bridges

Brunel oversaw the design and construction of many bridges and viaducts throughout his career. He built Maidenhead Bridge across the River Thames, the Wye Bridge at Chepstow, and the Royal Albert Bridge across the River Tamar.

Clifton Suspension Bridge

One of Brunel's defining achievements was the Clifton Suspension Bridge project. In 1830, he designed a 700 feet bridge to span across the Avon River. The bridge required two soaring masonry towers that reached 245 feet above the river gorge. The suspension bridge used tensioned cables to support the roadway. This tension allowed the bridge to use drastically less material and so became much cheaper to construct. Despite the lower cost of production, the project had many funding problems. It was completed after Brunel's death in 1864. The bridge is still in use today with over 4 million vehicles passing over it every year.

The Great Western Railway

In 1833, Brunel was appointed as chief engineer of the Great Western Railway. This ambitious project aimed to link London to Bristol by railway. Brunel spent days researching and surveying the geography of the 200 km route. He controversially chose the flattest approach through Reading and Swindon, which at the time were only small villages. These settlements later became hugely influential in the construction of railway works and helped turn them today into booming cities.

Despite the relative flatness of the land between London and Bristol, there were still many obstacles such as rivers, valleys and hills. Brunel applied his engineering expertise to overcome these with a series of viaducts, bridges, stations and tunnels. One of the most notable is the Box Hill Tunnel in Wiltshire. This 1.8-mile long tunnel was the longest railway tunnel of its time and boasts grand classical style architecture at its mouth.

Paddington Station

In 1838, Brunel began work with the architect, Matthew Digby Wyatt on the design and construction of Paddington Station. As the main terminal for the Great Western Railway, Brunel wanted the station to be the "largest of its class" and similar to the design of the recently completed Crystal Palace. The first train departed on the 16 January 1854, and the station is still seen as a resounding success today.

Shipping

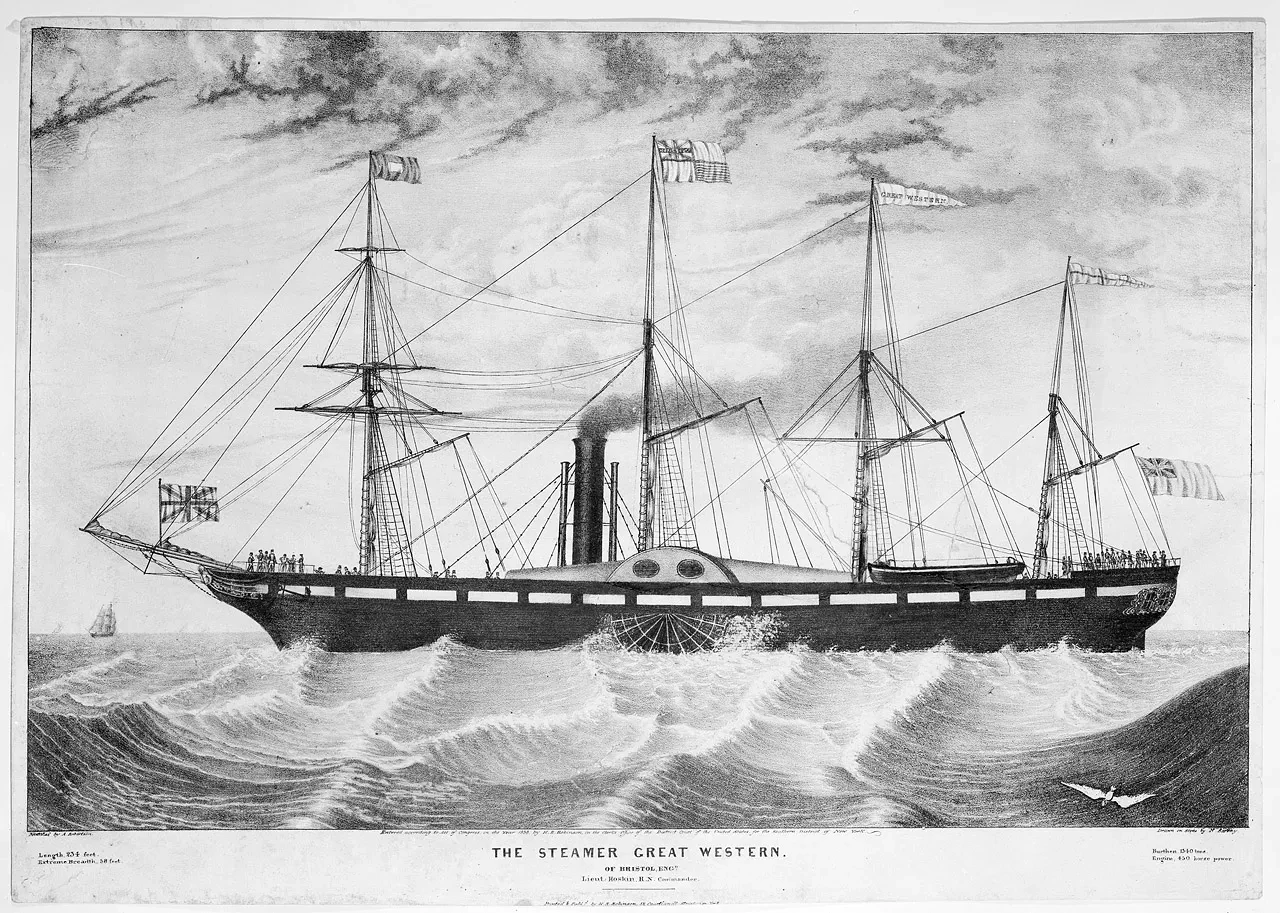

Even as the Great Western Railway was under construction, Brunel moved onto a new project in 1835, the design of a series of steamships for transatlantic shipping. Applying his theory that a large steamship would require less fuel than a smaller ship, Brunel offered his services to the shipping company for free. This resulted in the construction of the Great Western steamship which set sail in 1837. At the time, it was the largest steamship in the world. In 1843, Brunel completed work on the SS Great Britain, the world’s first iron ship, which became influential in the design of many modern sea vessels.

Hospitals

When Britain entered the Crimean war in 1854, Brunel was asked by the British Government to make a pre-fabricated hospital. The primary requirement was that the construction could be easily transported and built to Turkey. This pioneering design became known as Renkioi hospital. It took Brunel only six days to complete and was considered a great success for its attention hygiene and sanitation for a large number of occupants. The founder of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale, referred to Brunel’s creation as ‘Those magnificent huts’.

Brunel's steam ships

SS Great Western

It was always Brunel’s dream to expand the Great Western transport network so that it not only linked London to Bristol, but onwards to New York by steamship. This led to the construction of the SS Great Western in 1838, the first steamship purpose-built for crossing the Atlantic. She was an iron-strapped, wooden, side-wheel paddle steamer, with four masts to hoist the auxiliary sails. She was used regularly for transatlantic passenger travel between 1838 and 1846.

SS Great Britain

Brunel went on to design the SS Great Britain, regarded as the first modern steamship when launched in 1843. She was the largest ship of her time, built of metal, powered by an engine and driven by propeller rather than paddle wheel. Today, she has been fully restored and is on display in Bristol as a popular tourist attraction.

Discover more about the SS Great Britain on their website

SS Great Eastern

Brunel’s last project was designing the SS Great Eastern, built to take passengers non-stop from London to Sydney. It was an ambitious and groundbreaking feat of engineering, and the largest ship of its time. Brunel knew her affectionately as the ‘Great Babe’.

Sadly, Brunel, a heavy smoker, suffered a stroke just before Great Eastern's ill-fated maiden voyage in 1859, in which she was damaged by an explosion. Brunel died 10 days later, aged 53, leaving a pioneering legacy behind him.

Find out more about the Great Eastern

See more in our Maritime London gallery

How did Brunel die?

On the 5th September 1859, Brunel was onboard the SS Great Eastern, one of his most notable creations and the largest ship ever built in its time. As the ship tested its engines before setting sail for New York, Brunel had a stroke on deck. He returned to his home at 18 Duke Street, London where he died on 15 September 1859, aged fifty-three.

He was buried in the Brunel family vault at Kensal Green Cemetery, London. Memorials were quickly made, including a plaque at each end of the Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash which was opened just a few months before his death. This plaque can still be seen on the bridge today.