Although maritime records are not usually a starting point for compiling a genealogy, the archive at the National Maritime Museum will enable you to better understand the cultural context of this period, allow you to validate research you may have already carried out and supplement your knowledge.

The formative research for this guide was centred on formerly British colonies in the Caribbean. Although the collection does feature documents relating to former Dutch and French colonies, these are fewer in number in comparison to material relating to former British colonies.

This is a working document that may change over time as further research is carried out. We have consulted with researchers and experts from the African Caribbean community in forming this guide. If you wish to suggest an amendment or addition to the guide, please do not hesitate to get in touch.

This guide has been developed and written by members of the African Caribbean history research group at the National Maritime Museum.

Context of period

The majority of our material from the 1700s and 1800s relating to the Caribbean is linked to the transatlantic slave trade.

Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, between the 1500s and 1800s, saw the kidnapping and trafficking of millions of African people to the Americas and the Caribbean. People were sold into slavery, mainly to carry out unpaid labour on plantations in brutal conditions.

Chattel slavery, as adopted in Europe, the Americas and Caribbean, meant that enslaved people were treated as commodities that could be traded, sold and renamed according to the wishes of their owners across generations.

Due to the lack of recorded information about exactly who these people were, where they came from and where they went, it can be challenging for people of African Caribbean heritage to trace their family history and ancestry back from the Caribbean to a particular location in Africa.

This timeline offers a summary of events and British legislation from the late 1600s through to the mid-1800s relating to the transatlantic slave trade. It can be used to offer context to records that you may come across in the Caird Library and Archive.

1672 The Royal African Company is formed to set up military forts and monopolise trade along the West African coast. James, Duke of York (later King James II), is the largest shareholder.

1600 – 1700

Records suggest that approximately

1.9 million Africans are kidnapped and forced aboard ships to European colonies in the Caribbean, North and South America.

Britain traffics almost half a million captive Africans across the Atlantic.*

| 1697 | The Trade with Africa Act officially ends the Royal African Company’s monopoly over the trade of enslaved peoples. The right of free trade in enslaved peoples is recognised as a fundamental and natural right of Englishmen. | |

| 1713 | The Treaty of Utrecht is signed between Spain and Britain. Britain wins control of the Asiento, the contract for trafficking enslaved people from west Africa to Spanish south American and Caribbean colonies, for 30 years. | 1701 – 1800 Records suggest that approximately 5.8 million Africans are kidnapped and forced aboard ships to European colonies in the Caribbean, North and South America.

Britain traffics approximately 2.3 million captive Africans across the Atlantic.* |

| 1729 | Bristol overtakes London as Britain's main slave port with 48 recorded voyages in comparison with London’s 29. Ships from Bristol are responsible for trafficking over 15,000 people, just over 53 per cent of total number of people Britain, as a nation is responsible for in 1729. Liverpool has 15 ships involved in the slave trade. | |

| 1739 | After years of fighting, a peace treaty is signed with the Maroons, a community of Africans who had escaped from slavers in Jamaica. The treaty acknowledges their freedom and right to self-govern their own land. In return the Maroons agree to capture runaways and support the British government in Jamaica. | |

| 1771 | The James Somerset case ruling declares that enslaved people in England cannot be forcibly sent to the Caribbean. | |

| 1772 | The opening of the Bridgewater Canal sees Manchester's previously negligible export trade in cotton goods rises inexorably. A third of its business goes to Africa to be exchanged for enslaved people, the rest to the West Indies and North American colonies. | |

| 1783 | British Quakers present a petition signed by 300 people for a “bill for the regulation of the African trade” that aims to stop transatlantic slave trade in Parliament. | |

| 1786 | The French increase their share of trade in Africa and are perceived as encroaching on British interests. France becomes the second largest trafficker of enslaved people, behind Britain, by 1800. | |

| 1787 | The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade formed in London. | |

| 1790 | Britain reports 250,000 people enslaved in Jamaica. Jamaica produces 60,000 tonnes of sugar for Britain. | |

| 1793 | Toussaint Louverture leads the Haitian Revolution in the French colony St Domingue. Britain attempts to invade St Domingue during the revolution but fails. St-Domingue is now the principal source of sugar for continental Europe. | |

| 1796 | Liverpool now controls 70 per cent of the British slave trade and 40 per cent off the whole European slave trade. | |

| 1797 | Britain reports 300,000 people enslaved in Jamaica. | |

| 1800 | The British economy is now dependent on goods produced by enslaved peoples such as sugar, tobacco, cotton. 60 per cent of all British exports are sent to Africa and America to further support and fuel transatlantic slavery. British ships make approximately 1,340 voyages with 400,000 captives landing in the Americas. | |

| 1806 | The population of enslaved peoples in the Caribbean has increased by 25 per cent since 1790. White people in the Caribbean are outnumbered by Africans 1:7. | 1801– 1900 Records suggest that approximately 3.2 million are kidnapped and forced aboard ships to European colonies in the Caribbean, North and South America.

Britain traffics approximately 280,000 captive Africans across the Atlantic ocean. |

| 1807 | The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act makes it illegal to engage in the trade of enslaved peoples throughout British Colonies. A Royal Navy squadron is stationed off the west African coast to intercept and capture slaving vessels. A majority of the captive Africans found on-board these vessels are taken to, and left in, Sierra Leone. | |

| 1813 | A slave register is introduced to Trinidad as an experiment. The slave registration order states that any enslaved person not registered is to be considered free. | |

| 1815 | A slave register is introduced to Saint Lucia and Mauritius.

William Wilberforce, abolitionist campaigner and MP, introduces a bill to impose the registration system on all the colonies. | |

| 1817 | Slave registers are introduced to the majority of British colonies. | |

| 1823 | Following the failure of the Demerara uprising in British Guiana, 200 resistance fighters are beheaded as a warning and deterrent to enslaved people. | |

| 1831 | Samuel Sharpe, an enslaved Baptist deacon, leads an uprising in Jamaica. Over 200 plantations are attacked causing over £1,000,000 worth of damage. | |

| 1833 | A reformed parliament votes for the Slave Emancipation Act abolishing slavery throughout the British empire | |

| 1834 | The Slave Emancipation Act comes into effect. Although legally ‘free’, people are made to work as apprentices on the lands of European owners for little or no money. | |

| 1838 | On 1 August, apprenticeships are abolished. Enslaved people of British colonies are freed from enslavement

Asian migration to the Caribbean rises as indentured workers are brought into the region, predominantly from India, and in lesser numbers from China and Indonesia. | |

| 1848 | Slavery is abolished in all French territories including Martinique, Guadeloupe and Guyana. Denmark ends slavery in all its territories including the Virgin Islands (St. Croix, St. Thomas and St. John) | |

| 1863 | The Netherlands ends slavery in all its territories. |

*Data from the Trans-Atlantic Slavery Database.

These figures only indicate the number of captive Africans that were forced aboard slaving vessels. These figures do not take into account the people that were smuggled aboard illicitly or those that died during the journey. Nor do these figures highlight those that died in, or on their way to, slave forts along the coast of Africa.

Research parameters and constraints

This section will inform you of some of the constraints you should be aware of when carrying out family history research using the records in the Caird Library and Archive.

Individuals looking to carry out family history research often begin with the following information:

- Geographical location

- Name of a person

- Specified time period

Time periods represented in the collection

The majority of the documents within the collection that can be applied to research into African Caribbean family heritage are from the 1700s and 1800s.

The collection also contains 1915 crew lists that show the names of individuals that served on merchant navy vessels during the period of 1914 and 1915.

The Museum does not currently hold many records relating to the migration of peoples from the Caribbean that took place between 1940 and 1970.

Passenger lists and information about the individuals that arrived in the UK during this period can be found in The National Archives.

Geographical locations and forced migration

Enslaved, as well as free people of African descent often lived and worked on plantations in their own designated areas. Plantations are large estates or areas of land where crops are grown or harvested for the purpose of trade and business. It is here that community ties and relationships were often established and maintained.

Enslaved peoples were considered property and were sold as per the wishes of their owners. When this happened, families were split up and uprooted. The person who was sold was forcibly moved to another plantation. Newspaper cuttings have shown that in some cases, entire families were put up for sale together but we do not necessarily have bills of sale relating to these cases, and it is not certain whether these families remained together or were split up.

Bills of sales do not indicate whether or not an enslaved person had a family, but do indicate the location/address of the buyer and their respective plantation.

Free peoples would also have travelled to find suitable employment across plantations.

The names of plantations and estates may also have changed over time; this, however, can be cross-referenced via the UCL Legacies of British Slave Ownership database online.

Researchers should be aware of these factors in case they do not find an ancestor or person of interest in a geographical location they had initially expected.

Names

In the case of African Caribbean family history research, surnames can offer an insight into the location and status of an individual as well as the complexities of life on plantations during the period of transatlantic slavery.

Enslaved or freed people of African descent on a plantation would not have necessarily had the same surname across a plantation (that of the slave owner). Some individuals may have kept a name from their previous plantations, adopted their spouse’s surname, adopted a new name upon emancipation or kept the surname of their mother or father.

Upon the introduction of slave registers, people who did not already have a surname would have been given the surname of the slave owner.

The spelling of names also may have undergone change throughout generations for a variety of reasons: there may have been an error in documentation; the phonetic spelling of a name may have been given; a choice may have been made by the person to disassociate themselves from their former owners, and many other reasons. Because of this, researchers should be aware that a family name may not be found in its current form.

A majority of the slave registers are digitised and can be accessed on Ancestry.com via the Caird Library and Archive’s institutional account.

To better understand what documents in the Caird Library and Archive can be used to support your research, please see the collections document.

Collections

This section can help to inform you about what records are available in the Caird Library and Archive at the National Maritime Museum and how they can be used to support African Caribbean family history research.

The collection relating to the Caribbean is strongest in relation to the 1700s and 1800s. Although the collection contains crew lists from 1915, material relating to the migrations of people from the Caribbean between the 1940s and 1970s is not held at the National Maritime Museum and, instead, can be found at The National Archive.

Because of this, the collection held at the Caird Library and Archive may be more useful to researchers who have already traced their family ancestry back to a location in the Caribbean within this time period.

This is a working document that may change over time as further research is carried out. We have consulted with researchers and experts from the African Caribbean community in forming this guide. If you wish to suggest an amendment or addition to the guide, please do not hesitate to get in touch.

Michael Graham-Stewart Collection

The Michael Graham-Stewart Collection was purchased by the National Maritime Museum in 2002, having been assembled by Graham-Stewart over a period of 14 years. The Collection explores aspects of the West African, transatlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades from the mid-eighteenth to the early-twentieth centuries, and includes material relating to the abolition of slavery. The archive catalogued at the Caird Library and Archive incorporates manuscripts, printed books and pamphlets, maps and photographs.

Many of the documents featured in this guide are from this collection and can be identified by their ‘MGS’ code.

Newspaper cuttings

Newspaper cuttings offer an insight into the lifestyles of Europeans in the Caribbean. Newspapers would have been printed for European settlers in the Caribbean and reported life in its respective nation in relation to ongoing events in Europe. The import of goods featured heavily in newspapers, informing of what had come into the country and when they were available for purchase.

Advertisements for the sale of enslaved peoples currently on plantations are also featured in newspaper articles; many advertise a location and a very brief physical description of the peoples or person that the slave owner was attempting to sell. This also usually includes the name of the slave owner as well as their legal representatives present.

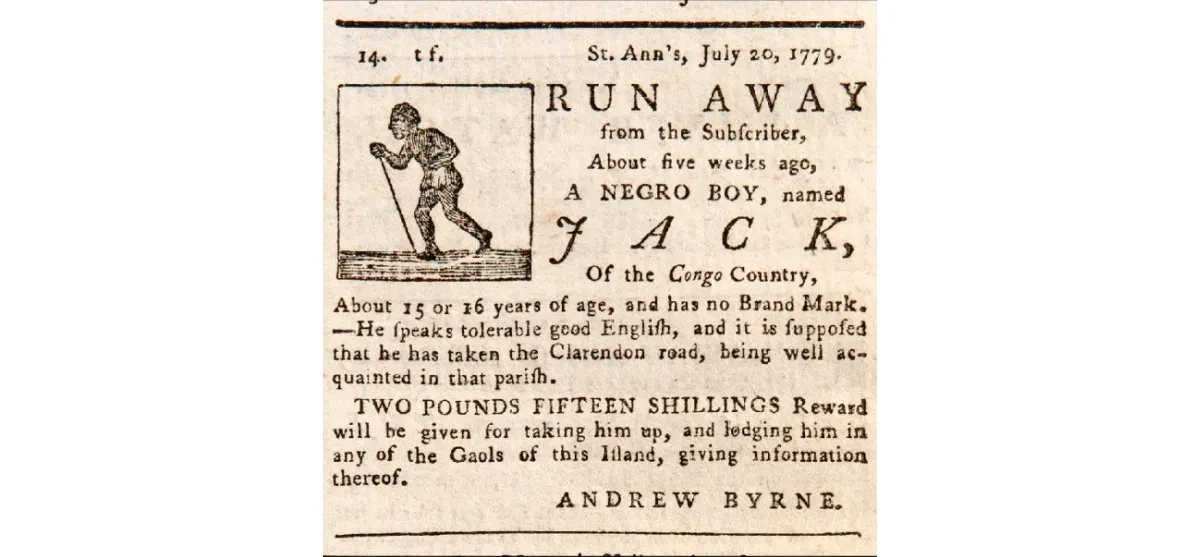

Newspaper cuttings also provide an insight into ‘runaways’; enslaved peoples who escaped from their plantations. ‘Runaway’ articles often include a name, and some will also include a surname.

Almost all articles relating to ‘runaways’ will provide a physical description of the person being sought. Some include a suspected whereabouts for the individual, offering an insight into family life, relationships and support networks enslaved people may have had across and outside of plantations.

Examples in the collection

| MGS/45 | See description with image above. |

| MGS/51 | Barbados Mercury and Bridge-Town Gazette, 1818. Containing articles for sale; ships arriving and departing; descriptions of runaways; plantations for sale including slaves; services wanted for hire; services offered for hire; no trespassing notice. |

| MGS/55 | The Royal Gazette, Jamaica. Containing articles for sale: 1811 plantations, settlements and lands; descriptions of runaways and absconders; rewards offered; the appointment of a new Lieutenant-governor; workhouses’ inmates to be sold by public auction. |

| MGS/50 | Bell’s Weekly Messenger, London, No. 911, Sun 12 Sep 1813. Containing an account of the high mortality rates among captive peoples in Charlestown due to poor conditions and treatment; a Lloyd’s List of ships affected in the Caribbean following a great hurricane; prices of sugar, coffee, cocoa and ginger and importations of arrowroot and castor oil. |

| MGS/46 | The Cornwall Chronicle and Jamaica General Advertiser, Montego-Bay, Jamaica, Sat 19 and Sat 26 Feb 1785. Contains references to slaves for sale, escaped slaves, etc. |

Correspondences

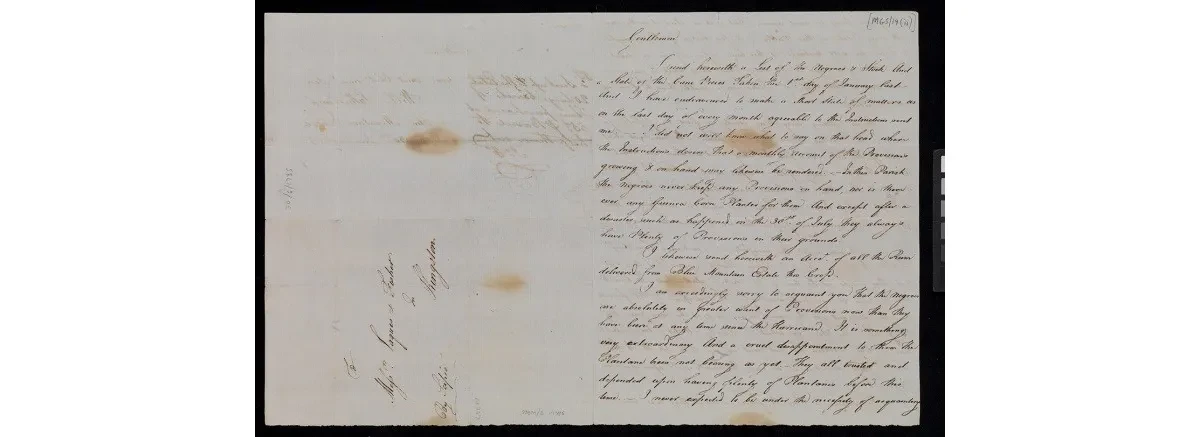

Written by Europeans in relation to events, business and general affairs on plantations, correspondences can be used to place plantations in the wider context of the wider economy of enslaved labour.

As letters were often written to owners and stakeholders who did not live in the Caribbean, we are able to read a summary of a plantation’s financial situation, its upcoming ventures and any business concerns.

These types of correspondences very rarely name or identify any particular individuals beyond those in leadership positions on plantations. We do not often have entire conversation chains, so researchers may not be able to track the response, or what preceded the correspondence.

Examples in the collection

| MGS/19 | See description with image above. |

| MGS/20 | Letter to William Atkinson of Sheffield, addressed from Augusta, Georgia, 23 Mar 1821. |

Inventories

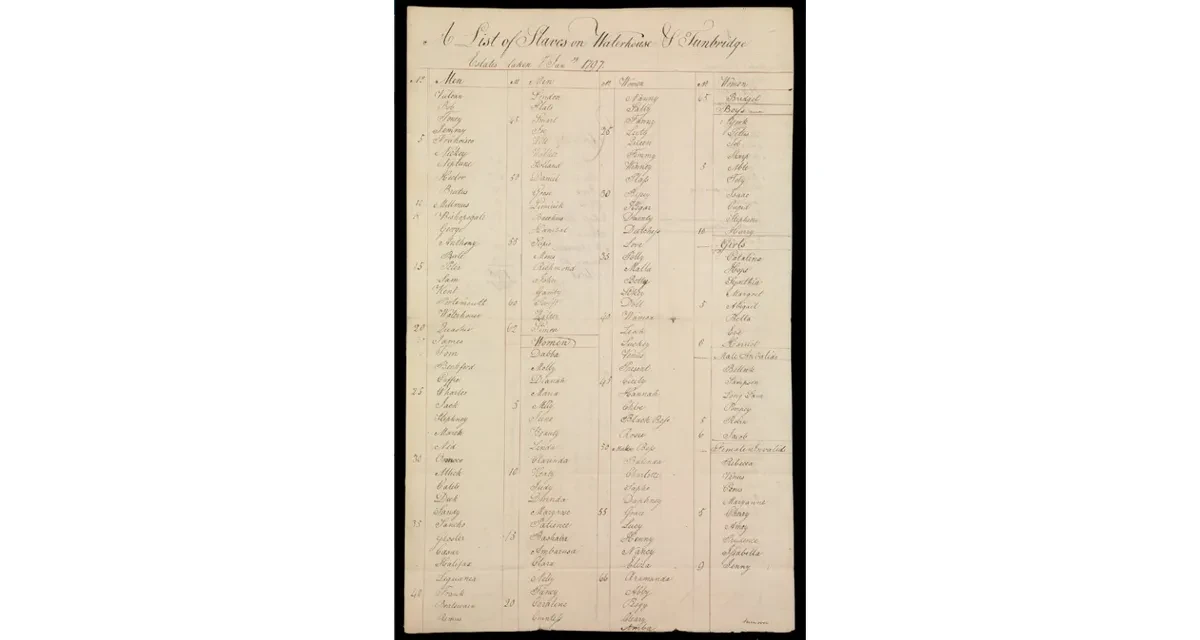

As slave owners considered enslaved people to be property, we are able to find information about people included in inventory reports.

Plantation inventory records provide an insight into the business of plantations, their production and crops, as well as the communities of enslaved and free people within them.

They can be useful in verifying knowledge or building a stronger contextual narrative of the wider community and the plantation during research.

The format of these reports range across plantations, but the information in the reports may touch on the following:

- Name (first)

- Gender

- Role/job

- Location on plantation

Examples in the collection

Inventory above, including 62 men, 65 women, 10 boys, 8 girls, 6 male invalids, 9 female invalids, 13 male children, 25 female children, and increase/decrease in slave numbers for 1796. The plantation was in St Andrew, Jamaica. (MGS/23)

| MGS/23 | See description with image above. |

| MGS/24 | Inventory of Plantation Mon Repos, the property of Joseph Hamer Esquire, deceased, situated on the East Coast of Demerary, taken the 1st July 1816. Lists of plantation acreage and buildings, followed by a list of the names (under 'Negroes') of 85 men, 70 women, 43 male children and 46 female children slaves, total of 244 individuals. |

Receipts/Bill of Sales/Auction Records

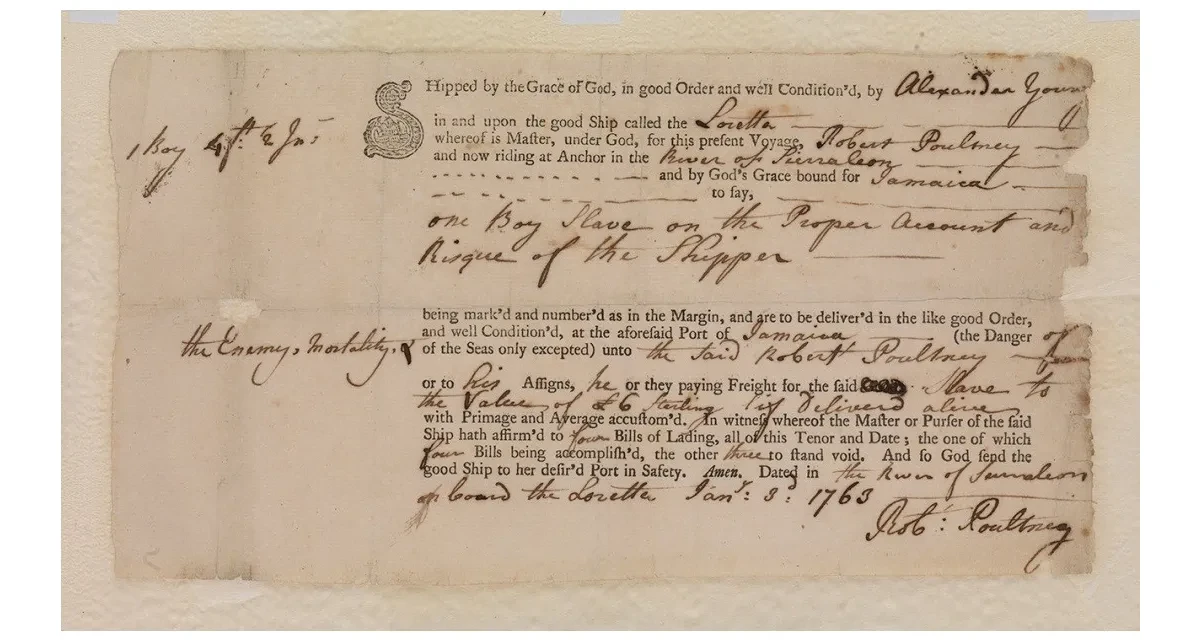

Bills of sales provide an insight into the price that was paid for enslaved or captive peoples. Bills of sales range in format. They often show transactions of groups of people being sold at once and feature no descriptions of the people in question.

Very few contain the names of the enslaved or captive people being sold; this will most often be the case if only one person is being sold as part of the sale.

From the pricing and format of the receipt, researchers can attempt to ascertain the importance of the individual being sold.

Very rarely will it say what the individual is being sold for, as this will largely be the decision of the slave-owner.

Examples in the collection

| MGS/2 | Slave registration certificate, Slave Registry Office, Cape Town, Cape of Good Hope, 15 Aug 1826, detailing the registration of a male infant, named Japi, born on 4 Aug 1826, whose mother was named Theresia, housemaid, property of Mr Daniel Krynauw Senior. |

| MGS/8 | Receipt dated 9 May 1804 for 26 'new Negroe men' from the ship ANN from Cape Mount, Kingston, Jamaica, bought by HM Government from George Kinghorn as recruits for HM's Second West India Regiment at Fort Augusta for £2,340 (at £90 per head). |

| MGS/9 | Receipt for the purchase of a slave by Miss Maria Potinger from John Hinde & Co. in Kingston, Jamaica, 30 May 1807, with tax blind stamp, for one new Negro woman, from the BEDFORD, Capt Newman, for £110. |

| MGS/14 | Shipping bill certifying the loading of 'one slave boy', valued at £6 sterling, shipped by Alexander Young on the ship LORETTA (Robert Poulsney, Master), on the River Sierra Leone, bound for Jamaica, dated 3 Jan 1763. |

Lloyd’s List

Between 1500–1800, over 35,000 slave voyages carried millions of Africans to the Americas (including North America, the Caribbean, and Brazil). From 1734 to the present day, the Lloyd's List has provided regular updates about shipping news.

The Lloyd’s List provided a reliable and concise source of information for the merchants' agents and insurance underwriters to negotiate insurance coverage for trading vessels. From a research perspective, the list provides us with insight into the movement of a particular vessel, where it was coming from and going to.

The database has been largely digitised for this purpose on the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, but the paper records can be ordered and accessed at the National Maritime Museum.

We recommend consulting the Lloyd’s List research guide before ordering any of the records:

A brief history and introduction to the Lloyd’s List: https://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/researchers/research-guides/research-guide-h1-lloyds-lloyds-list-brief-history

Index List:

Crew lists

The 1915 British Merchant Navy crew lists (RSS/CL/1915/) are a valuable resource for family historians searching for people who may have served on board a British merchant navy vessel during this period. References to Caribbean locations are largely in relation to the birthplace of the crew member. Researchers can search through these lists to search for surnames or place of birth. Please be aware of potential spelling errors or variations in the surname.

Please see below for links to the following locations mentioned in the crew lists:

Virgin Islands (British) (Tortola)

St Vincent and the Grenadines

Please note that this is a digital document and is constantly growing with research. If there is a location that is not listed here, it can be searched via the ‘birth place’ search bar. If you would like to add a location to the guide, please do not hesitate to get in touch.

Further research and reading lists:

Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain – Peter Fryer

A Tree Without Roots: The Guide to Tracing British, African, and Asian Caribbean Ancestry – Paul Crooks

The Family Tree Toolkit: A Comprehensive Guide to Uncovering Your Ancestry and Researching Genealogy – Kenyatta D. Berry

Tracing your Caribbean Ancestors: A National Archives Guide – Guy Grannum

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa – Walter Rodney

Black and British: A Forgotten History – David Olusoga

Useful links:

National Archives – Family History and Individuals from the Caribbean

Researching African-Caribbean Family History - BBC

UCL Legacies of British Slave Ownership

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database

Former British Colonial Dependencies, Slave Registers, 1813-1834