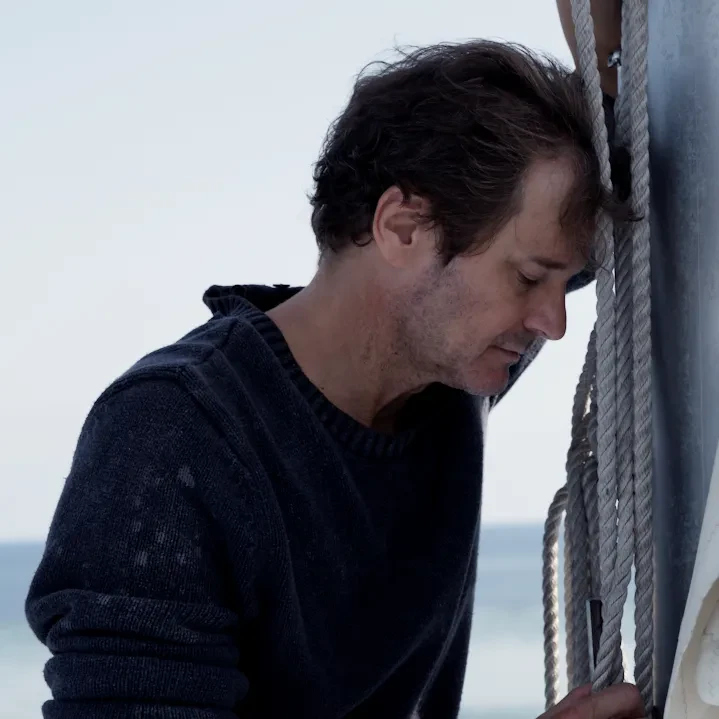

The Mercy starring Colin Firth portrays Donald Crowhurst's tragic attempt to sail around the world single-handedly in the first race of its kind. Maritime specialist Jeremy Michell sheds light on the perils of sailing alone, the progress of yacht racing, and the importance of remembering failure.

By Kate Wilkinson

Visit the National Maritime Museum

The thrill of the race

Fifty years ago, the Sunday Times Golden Globe became the first solo non-stop round-the-world yacht race. Building on the international celebrity of Francis Chichester’s circumnavigation in 1966-67, the UK newspaper launched a sailing event to capture the world’s imagination – the ultimate competition of skill and endurance, and open to anyone, amateurs included.

'Yacht racing in this country has always been big, but it tended to be fairly elitist in the past,' says Jeremy Michell, a sailing instructor and part of the National Maritime Museum’s curatorial team, 'The Golden Globe opened up in a more popular mind the idea that people who are not wealthy could go and take part.'

Yachting really began when King Charles II brought his enthusiasm for the activity to England on return from exile in 1660 and raced yachts down the Thames against his brother for huge wagers. In the late 1870s, Lord Brassey achieved the first circumnavigation by a private yacht, building himself a steam-assisted three-masted schooner called 'Sunbeam' and sailing round the world with his family. The boat's figurehead is on display in the National Maritime Museum.

The Golden Globe opened up in a more popular mind the idea that people who are not wealthy could go and take part.

Struggling businessman and sailing amateur Donald Crowhurst was the classic underdog when he entered the 1968 competition. Putting everything into the race, he had signed a contract with his sponsor whose penalty clause meant that he would forfeit his house and business if he didn’t finish.

A doomed adventure

Crowhurst waved goodbye to his wife and four children on the race’s last eligible day aboard the Teignmouth Electron, a trimaran he had barely sailed before setting off. He had planned to equip the vessel with his own safety features, the success of which he hoped would revive his business in maritime navigational technology, Electron Utilisation Ltd. But he hadn’t completed the work before leaving British shores, leaving him in the process of tweaking while sailing.

It didn’t take Crowhurst long to realise how perilously ill-equipped he would be to tackle the waves of the Southern Ocean. If he continued he could die, but quitting would ruin him financially.

For a while it seemed like the plucky amateur could steal the race when Crowhurst started reporting false coordinates showing incredible gains in distance. The deception ended when after weeks alone at sea under immense physical, personal, and financial pressure, he died by suicide. This seemed the most likely cause of his disappearance: when rescuers found his abandoned trimaran, they discovered log books and reams of diary entries showing a collapsing mind.

Crowhurst’s tragedy caused a worldwide sensation. The Sunday Times Golden Globe didn’t run again, and its winner, Robin Knox-Johnston donated his £5,000 winnings to Crowhurst’s grieving family. Knox-Johnston was the only entrant to complete the race, with the other entrants forced to retire along the way.

Solitude at sea

Crowhurst’s behaviour was seen by many as foolish and reckless. He was certainly underprepared, and his false reporting put unnecessary pressure on his fellow competitors. One bad decision followed another, and he was soon lost in a nightmare predicament. How could he let things go so wrong?

Michell says it’s important not to underestimate both the physical and mental challenge of a solo voyage: 'Unless you have done that sort of race, it’s very difficult to make a judgement call as to what the trigger points are to make someone lose their mind in that way and potentially commit suicide.'

Alone at sea, you might catch about 20 minutes of sleep before you’re up again doing something. Performing the roles of a whole crew, you have to be mentally alert all the time. A small change of sound on the boat might wake you up.

Unless you have done that sort of race, it’s very difficult to make a judgement call as to what the trigger points are to make someone lose their mind in that way and potentially commit suicide.

Not only that, without anyone to talk to, 'you’ve got no one to relieve any emotional issues you might have, whether that’s frustration, anger, sadness, loneliness.' Michell knows those who have sailed long distances on their own. During one transatlantic voyage, a friend would call any ship he saw just for the sake of another voice (as well as to confirm his position with their navigation): 'He said you could end up in tears over the most stupid things because it’s the only emotional release you have.'

Though at home it might seem bizarre, when you’re on your own it’s a very different emotional experience, Michell says.

21st Century racing

Though the stakes are high, sailing around the world single-handedly continues to present an appealing challenge. Yachting is as popular as ever and there have been numerous successful racing events world-wide.

What has changed in yacht racing between now and Crowhurst’s day?

Michell lists the improvements to on board technology: the use of hydraulics to keep the yacht stable, electronic equipment for winches, hoisting and dropping sails. Most importantly, there’s the communication. Satellite telephones and beacons allow people to know where you are. In short, 'there’s a lot more of a safety net,' Michell says.

Today it would be unimaginable for a sailor of Crowhurst’s limited experience to take part in such a demanding voyage. The Vendée Globe, a single-handed non-stop round-the-world race founded in 1989, requires its entrants to undertake survival training before participating.

Commemorating failure

Royal Museums Greenwich plays host to some of the most dramatic, awe-inspiring, and successful maritime stories through the objects on display and in conservation. John Harrison’s 18th Century marine timekeepers in the Royal Observatory were the first instruments to solve the problem of finding longitude at sea.

Also in our collection is Donald Crowhurst’s ‘Navicator’, which he produced and took with him on his doomed voyage. On free display in the Queen’s House is a series of striking photographs by artist Tacita Dean, of Crowhurst’s abandoned trimaran on the coast of the island Cayman Brac. In the National Maritime Museum you can find the artist's carving, of the words 'It is the mercy', which refer to Crowhurst's final diary entry.

So why do we preserve the memory of such a sad event in maritime history?

'It’s always good to remember that life isn’t one long successful winning streak,' Michell says, 'it was never obvious that Britain would be a top maritime nation: it happened through incidences, setbacks, circumstances, failures and successes. In terms of sailing and our yachting industry, it’s exactly the same.'

Crowhurst’s story is a useful reminder of the dangers of yachting, and would have made an impact on the regulation of similar racing events since 1968. 'Out of failure can come some kind of success that makes it safer for other people,' Michell says.

The race’s revival

2018 marks the 50th anniversary of that first ill-fated race. Following a number of books and documentaries over the years, Colin Firth plays Crowhurst in the upcoming film, The Mercy, which is set to fascinate audiences anew. In an earlier preview of the film last year, Robin Knox-Johnston expressed his satisfaction with the film in an interview with Yachting & Boating World magazine.

Later in the year, the Golden Globe race will be re-launched to test sailors under the same circumstances that Crowhurst and Knox-Johnston faced. No modern satellite technology is allowed for navigation – instead competitors must use their skills with instruments such as sextants to make the necessary calculations to steer a good course.

As a safety measure, the race’s website states that:

'All entrants will be tracked 24/7 by satellite, but competitors will not be able to interrogate this information unless an emergency arises and they break open their sealed safety box containing a GPS and satellite phone.'

Also unlike the original race, entrants must show prior ocean sailing experience of at least 8,000 miles and another 2,000 miles solo.

In July the competitors will set off for a challenge like no other.

Even after 50 years, the events of 1968 continue to both haunt and inspire the world’s imagination.

Banner image: 'It is the mercy' by Tacita Dean, courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery.