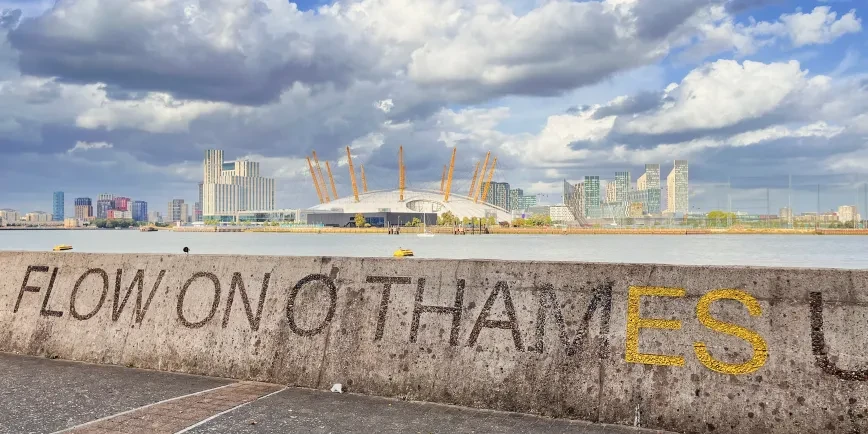

Like most people in the UK, I am an islander who has never been to sea.

Britain has a long and celebrated history as a seafaring nation, shaped by its island geography and strategic maritime position. However, today most of us don’t think much about the seafarers who transport over 90 per cent of everything we buy.

I would like to change that.

In October 2025 I embarked on my first voyage on a container ship, kindly facilitated by Ellerman City Liners.

The fieldwork trip is part of a research project exploring the lived experiences of contemporary seafarers, aiming to bring their often-unseen stories to light through photography, film and first-hand testimony.

The fieldwork gave me a glimpse into a space that is usually out of reach, yet so vital to our daily lives.

Ships in the night

My week aboard the MV Nova from Tilbury to the Port of Gdynia in Poland was an incredible first step into the maritime world.

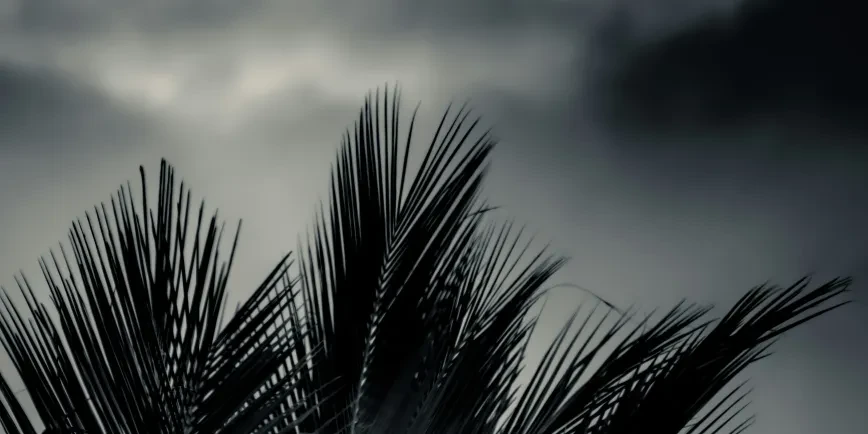

On reaching Tilbury I was introduced to several staff members as I walked through the port operations offices, and was met with alarmed faces when they heard that I was about the cross the North Sea. Didn’t I know about Storm Amy’s imminent arrival? I did now!

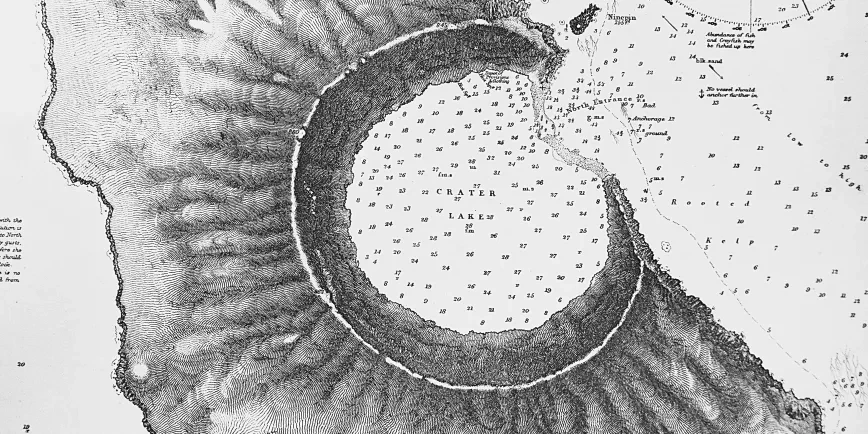

Much to my relief, the captain was an (admittedly young) ‘old hand’, and we managed to avoid the storm by hugging the coast and traversing the Kiel Canal, a 61-mile-long freshwater canal that links the North Sea to the Baltic Sea.

Many ships had taken the same precaution that night, so we were left waiting at anchor for several hours for our spot in the queue. This led to one of my first unexpected insights: just how dark the bridge needs to be kept in order for the navigating officers to see clearly at night.

'The most important person on board'

Nova is considered a small container ship, holding just under a thousand standard container boxes (also known as TEUs, or Twenty-foot Equivalent Units). The largest container ships by contrast carry more than 24,000. However, to a civilian, the Nova still feels like a giant vessel for a crew of 14.

There were six German and Ukrainian officers and eight Filipino ‘ratings’ (non-officers), including the cook.

Reynaldo, the chief cook, did an amazing job pleasing the very different appetites of the crew. It is regularly said that the cook is the most important person on board, and luckily for this crew, Reynaldo worked very hard to keep everyone happy. I think I ate better than I do at home.

World in motion

One of the porthole windows in my cabin faced forward, where the containers are stacked up, so I had a front row seat for cargo operations.

At the dockside in Gdynia, the cranes moved with measured grace, their long arms sweeping through the air. Below, the containers rose and fell: immense steel boxes shifting from ship to shore and back again, in a steady rhythm that feels almost ceremonial. The metal containers clanged and echoed as they settled into place, merging with the soft wash of the tide.

In this moment, industry becomes choreography: a dance of precision and patience, where the ship, slowly filling or emptying, seems to breathe with the pulse of the world.

Inside the engine room

The accommodation, kitchen, lounge and bridge were all located above the engine room, so there was no getting away from the thrum of the engines. It was the soundtrack to my day and night, although it became a benevolent hum surprisingly quickly.

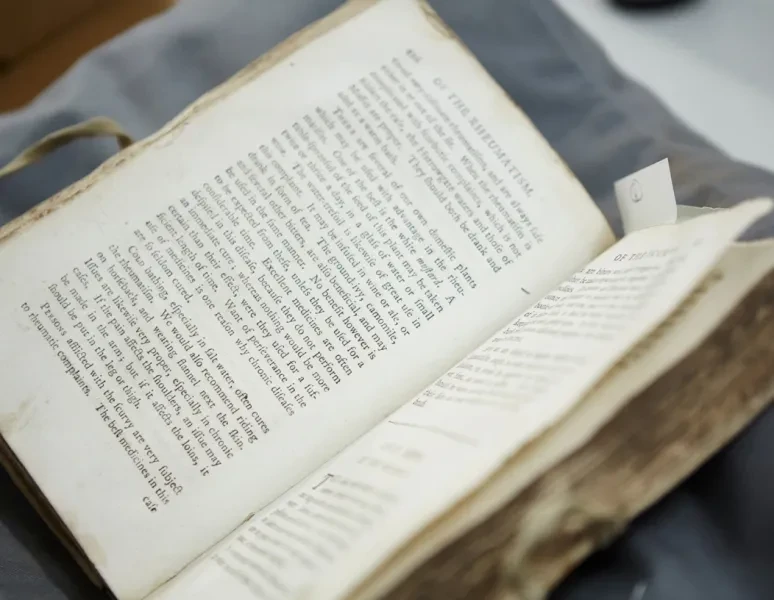

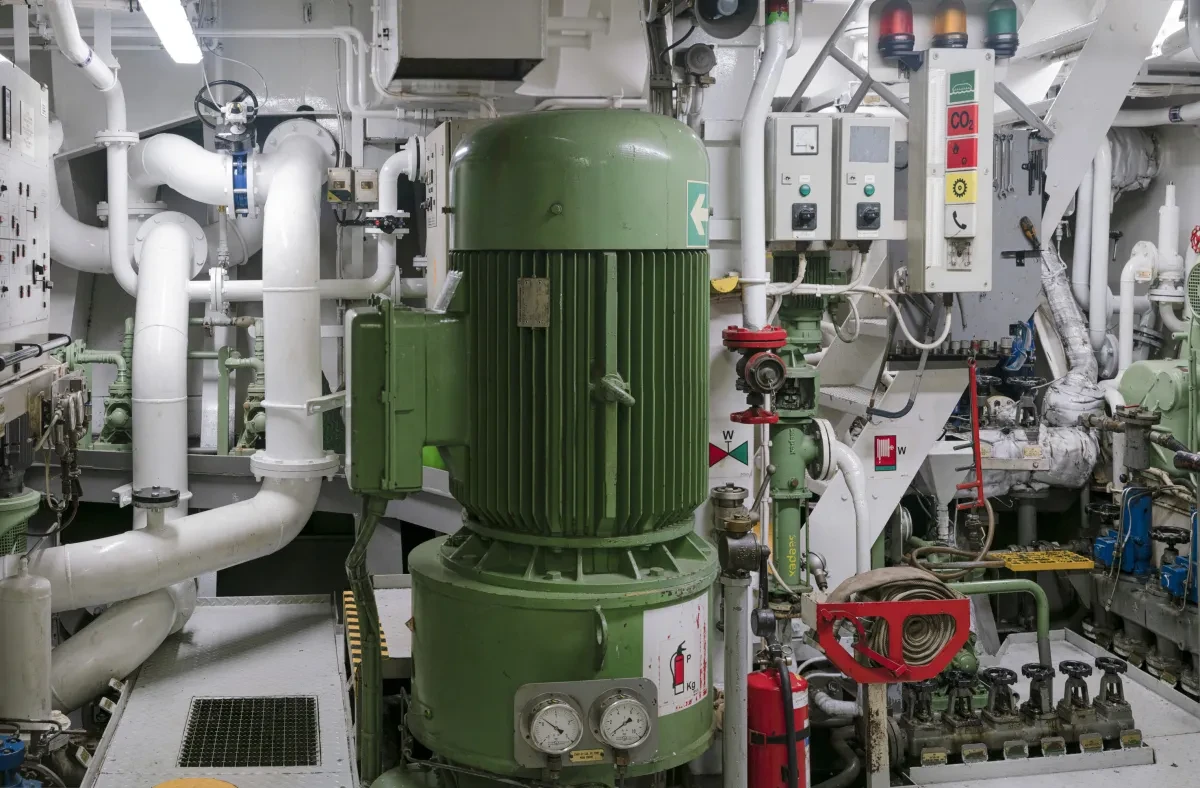

The engine room of a container ship is a vast, resonant space: the mechanical heartbeat of the vessel. It hums with deep, rhythmic power, and every surface gently vibrates to the pulse of the main engine. The air is warm and thick, infused with oil, metal and the subtle scent of salt from the sea. Networks of pipes, valves and gauges run in organised but organic-looking order along the walls, at times reminiscent of HR Giger’s biomechanical artworks.

Engineers moved with quiet skill amidst the noise and heat, their gestures practised and confident, tending to the unseen life that propels the enormous ship through the water.

Work and play

It was great to meet the second engineer, Tina Herm, a rare female crew member (only one per cent of seafarers are women). Tina was very impressive and certainly held her own in the engine room, also teaching the new cadet Mauritz while I was there. And one night, she demonstrated her boxing skills with the ship’s punching bag.

Far from home

The crew were very welcoming to a stranger in their midst, making time for me amongst their complex shift patterns and busy schedules. I managed to interview everybody on board, some more formally than others, but each person offered a fantastic insight into their life so far at sea.

I learnt about travels to every continent and heard some stomach-churning weather stories. I also witnessed what it was like to confront an arduous job with a tight-knit group of comrades – relationships which make the time away from loved ones much more bearable.

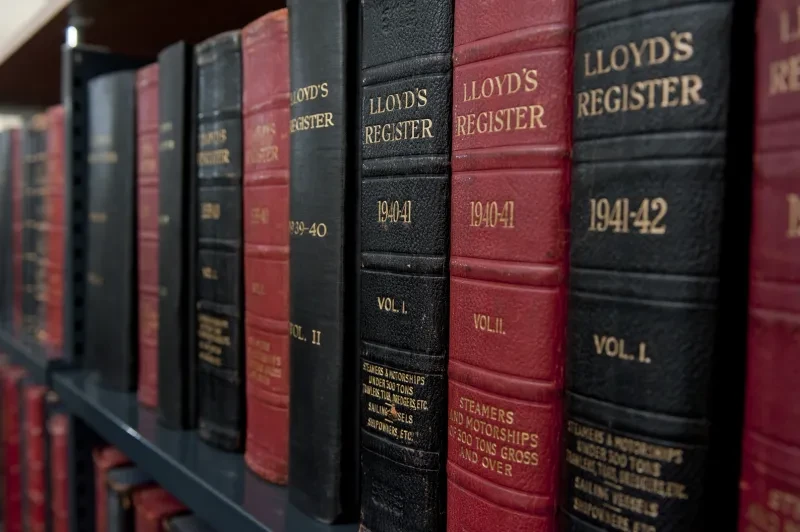

Follow the project

Zoe Childerley is working on is a REACH Collaborative Doctoral Partnership PhD, supported by the National Maritime Museum and the University of Brighton. She is utilising photography, film and sound, collaborating with seafarers in creating a body of work inspired by maritime archives and fieldwork on board ships and in ports. Find more of Zoe's work on her website, or follow her progress on Instagram.

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.

Main image © Zoe Childerley