James Creassy’s journal (Item ID: JOD/304) is over 300 pages long and written in perfectly legible handwriting – a rare find for material from 1777! He does not say why he is travelling to Bengal, but records in detail the entertaining, dramatic and sometimes rather distressing events that take place during the journey.

by Hannah Tame, Library Assistant

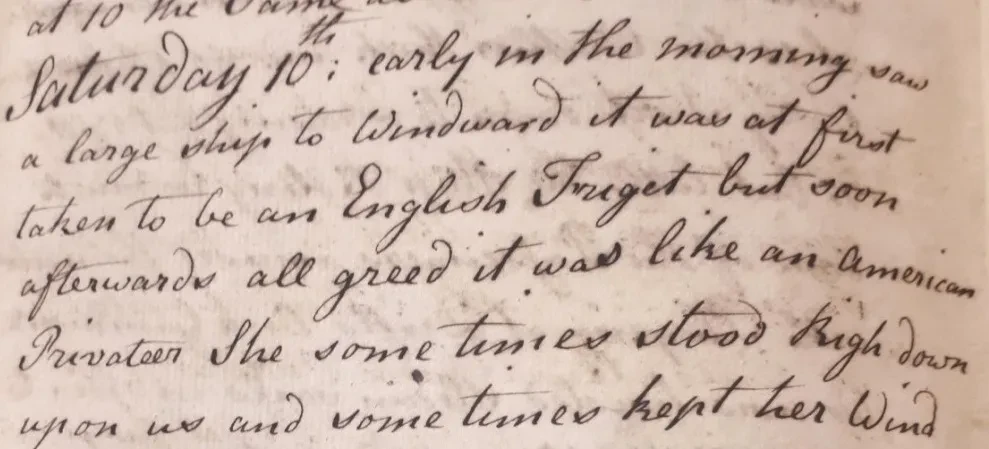

Saturday 10th May 1777: Mistaking a friend for an enemy

After being at sea for little more than ten days, Creassy records two ships in close pursuit of the Seahorse, The Prince of Wales and the Valliant.

'A little before 10 o’clock the drum beat to armes and everyone seemed ready to do their best to defend the ship.’

The chase comes to rather an abrupt halt when ‘the stern most ship came up and spoke with us. We wrote letters to send to England by her, she sheared off and went to chase a brig.’

‘There did not appear to be the least signes of fear in any one person on board, not even in the little boys. Still everybody seemed well pleased that we had been deceived in taking a friend for an enemy.’

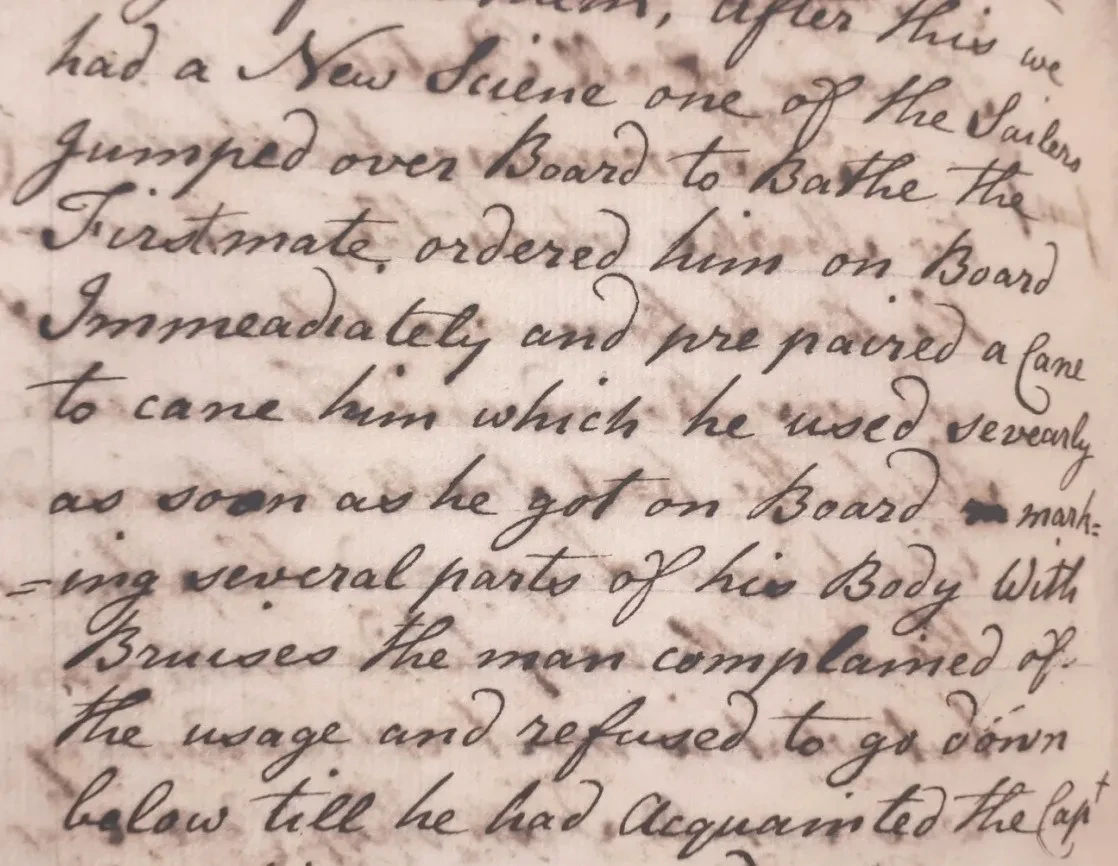

June 1st 1777: Keeping the peace below deck

As time goes on, with water supplies running low, and no sign of land, Captain Arthur struggles to keep the peace between crew and passengers. Creassy records one sailor defying the rules by jumping overboard to bathe, the sailor soon endures a severe punishment (see extract).

September 22nd 1777: ‘The Fairer Sex’

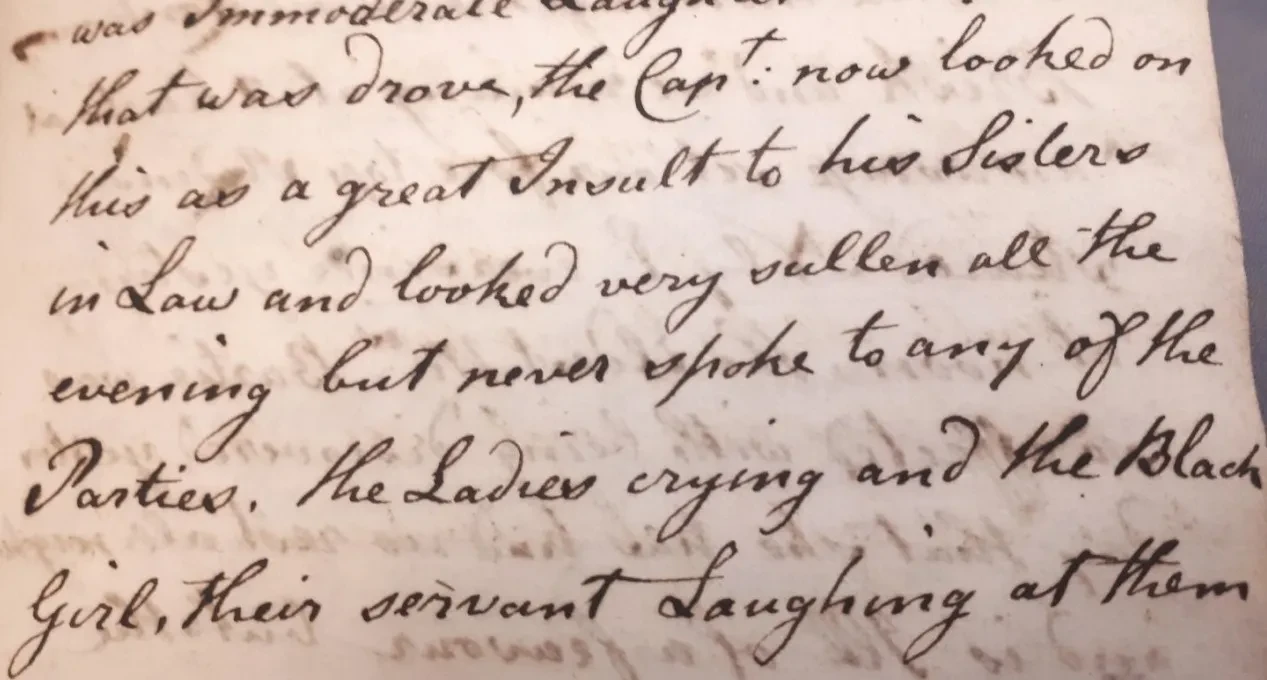

During the East India Company’s early years, women were not allowed to travel to the East Indies, despite numerous pleas from sailors not wishing to leave their wives behind. At least two women are listed on board the Seahorse and the Captain’s sisters in law seem to be particularly skilled in making mischief on board.

'in Mr Simpsons cabin they discovered somebody peeping out of the ladies cabin, the ladies had made a large hole to observe all that passed in Mr Simpsons (First Mate) birth which they could open and shut at pleasure. The gentlemen all by turns looked in to the ladies cabin and could see what passed there.' The ladies are ‘much alarmed, and tell Capt. Arthur that the gentlemen had made the hole. The Capt. looked on this as a great insult to his sisters in law.’

The ladies put on a good act and the whole situation then becomes something of a theatre production, as is shown in the extract below:

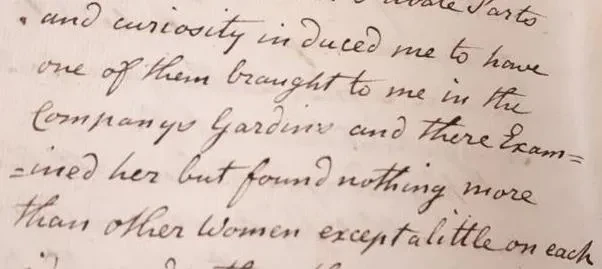

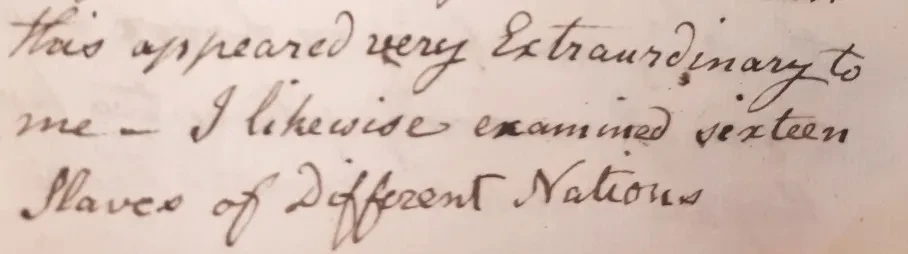

9th August 1777: An examination of Slaves

In contrast to the previous light hearted portrayal of the boundaries between men and women on board; James Creassy writes a rather graphic and violating account of his examination of ‘sixteen slaves of different nations’.

Shocking though it may seem, this kind of degrading mistreatment would not have been uncommon amongst slaves. Slave Traders often examined slave women in particular, for their reproductive capabilities. Creassy however is not a slave trader; he examines slaves seemingly out of perversion and curiosity, simply because he has the power to do so.

Lasting Impressions

After reading the innermost thoughts of this complex character, I was intrigued to find out what happens after Creassy’s journal ends in November 1777.

The British Library holds the India Office records and Private Papers, these resources helped me to clarify that Creassy was not on the Seahorse’s return voyage to England in 1778.

Within our library collection are the Memoirs of William Hickey (Item ID: PBD5858/1-4). Hickey travelled with James Creassy on the Seahorse, and describes him as an ’extraordinary creature’ and ‘vulgar fellow’. The memoirs also state that Creassy was travelling on to India to work as head conductor of intended Engineer works for The East India Company in Bengal. This information gave me the necessary information to link Creassy to a report held by the British Library which explains that:

‘In 1778 whilst working as the Superintendent of public works in Calcutta, James Creassy is taken to the Supreme Court and denied the right to trial by jury for the assault, battery and false imprisonment of two Indian Carpenters’.

Creassy’s case was the catalyst for a petition to change the law in India. This petition ultimately forced Parliament to reform the Bengal Supreme Court in 1781. It also called for restrictions on legal actions by Indians and the re-establishment of the ‘inherent, unalienable and indefeasible’ rights granted to Englishmen in Magna Carta.

I feel very lucky to have accidentally come across such an intriguing first-hand account that covers such a wide range of historical topics. I also suspect that I have barely scratched the surface on what could be unearthed about the curious character of James Creassy.