This portable telescope came to the conservation studio at the Prince Philip Maritime Collections Centre with multiple issues caused by insect damage.

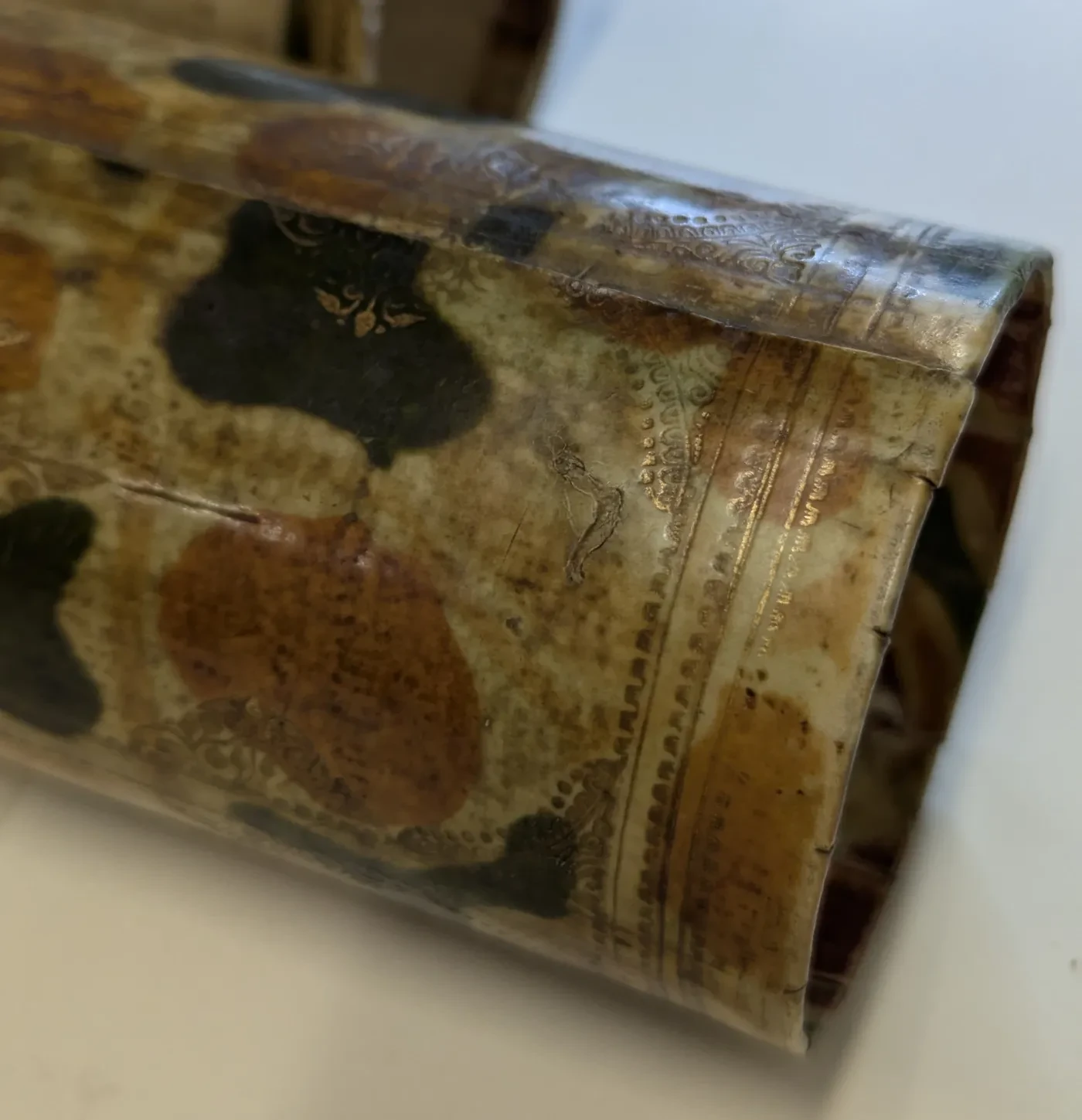

There were lots of tunnels in the vellum and paper tubes, as well as holes all the way through the telescope.

Telescopes are a popular target for many museum pests, including carpet beetles, clothes moths and other pests that target keratinaceous materials (a protein found in animal products like leather and vellum). Silverfish and booklice are also common pests for telescopes that contain paper.

Since the telescope had been selected for display, it needed to be treated to improve its stability and appearance. But first, we needed to learn what we could about how it was made in the first place.

Help care for the collection: Conservation work requires time and expertise. Your donations directly support this hands-on care, allowing objects to be protected and displayed for everyone to enjoy: donate today.

How was the telescope made?

The telescope is made up of seven paper draw tubes covered in vellum and a barrel with dyed vellum and gold decoration. Vellum is a special kind of parchment made from calf leather and can be very fragile.

This object is an example of an early telescope. Made around 1690, it is only about 80 years younger than the first ever patented telescope, which was made in 1608. At this time telescopes needed to be very long to get a clear image; this telescope can be extended to over two metres in length.

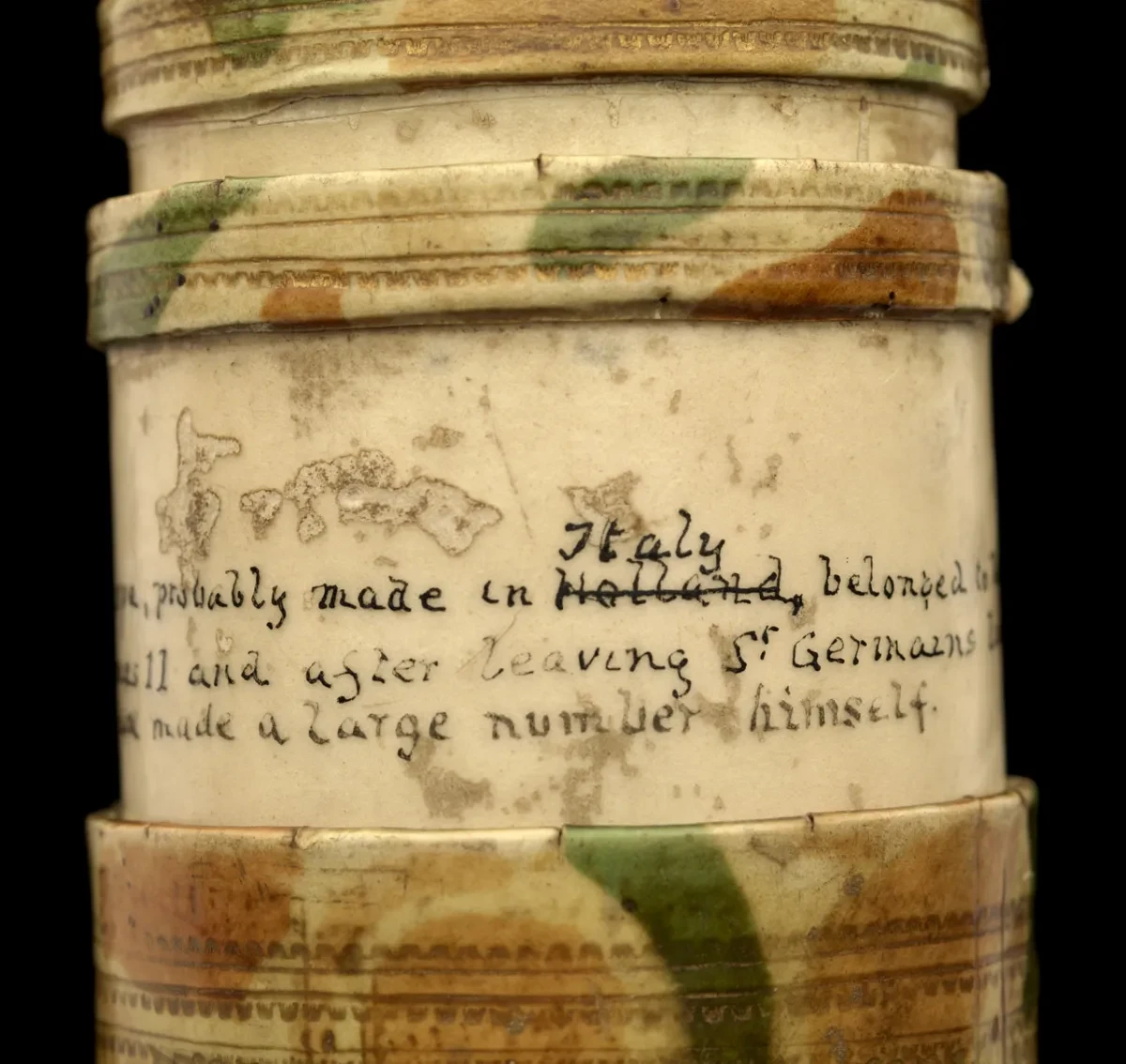

An inscription on the largest draw tube gives some more information about the object:

"This telescope, probably made in Holland Italy, belonged to the Reverend Doctor Ralph Taylor who went into exile with James II and after leaving St Germains lived for a time at Rotterdam. Galileo is said to have made a large number himself."

Find more photos and information about the telescope here

The strikethrough in the inscription poses an interesting question about whether this was a later change, or whether the mistake occurred during the inscribing but was simply crossed out and changed due to the cost of the materials. If the inscription was added after the telescope was fully made, it probably would have been too expensive to change the vellum out and start again.

Ralph Taylor (1647-1722) was an English clergyman and chaplain at the court of King James II at St-Germain-en-Laye in France. He is known to have owned at least two telescopes currently in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection. The other, a pocket telescope, is a companion to this and may have been made as a pair.

The colourful barrel of the telescope has also become very faded over time due to light exposure.

When the telescope was dismantled it was clear that the colours were once much brighter: compared to the insides of the barrels, the colours on the outside are far more muted. This is not something can be addressed during conservation treatment, but it is interesting to understand that the object’s appearance was originally quite different.

Conservation begins

Although this object came to be treated by Object Conservators, many of the materials are more commonly found in paper conservation projects.

The barrel and draw tubes are made from paper, and vellum is often used in charts and book coverings. Therefore, following consultation with colleagues from the Paper Conservation studio, methods and materials most often used in book and paper conservation were selected for the treatment.

Stabilisation

Pieces of the vellum coverings that had started to lift up were stuck down using wheat starch paste – an adhesive made from purified wheat starch powder and water.

This adhesive is used regularly on paper objects. Wheat starch and water are cooked to form a paste, then strained to get a smooth consistency.

This was applied sparingly to avoid adding too much moisture to the paper or vellum. The application of too much water can chemically interact with the cellulose; as water reacts with the acids in paper, cellulose chains break down and the paper becomes weaker.

Vellum is also very vulnerable to damage from moisture, which can cause shrinkage, deformation and even total breakdown of the collagen fibres—this is known as gelatinisation.

Where insect activity had left tunnels or holes, a thicker paste was used to fill the gaps. This was made from wheat starch paste mixed with the pulp of Japanese tissue paper, an acid-free conservation-grade paper.

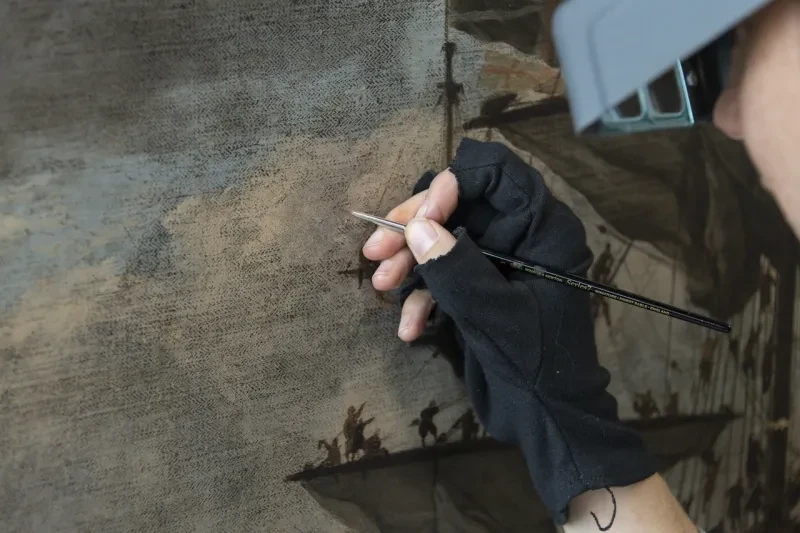

This paste was applied in very thin layers to areas of damage, letting each layer dry fully before the next was put on. This had to be done very carefully with a sewing pin, as some of the holes were so small.

Treatments such as this require a very steady hand, as even small mistakes in application can introduce moisture to the wrong areas or even scratch the vellum surface if the needle is positioned incorrectly. A high degree of dexterity is required, and it takes many hours under a magnifying glass and microscope to place the fills properly without damaging the surrounding paper and vellum.

Aesthetic treatment

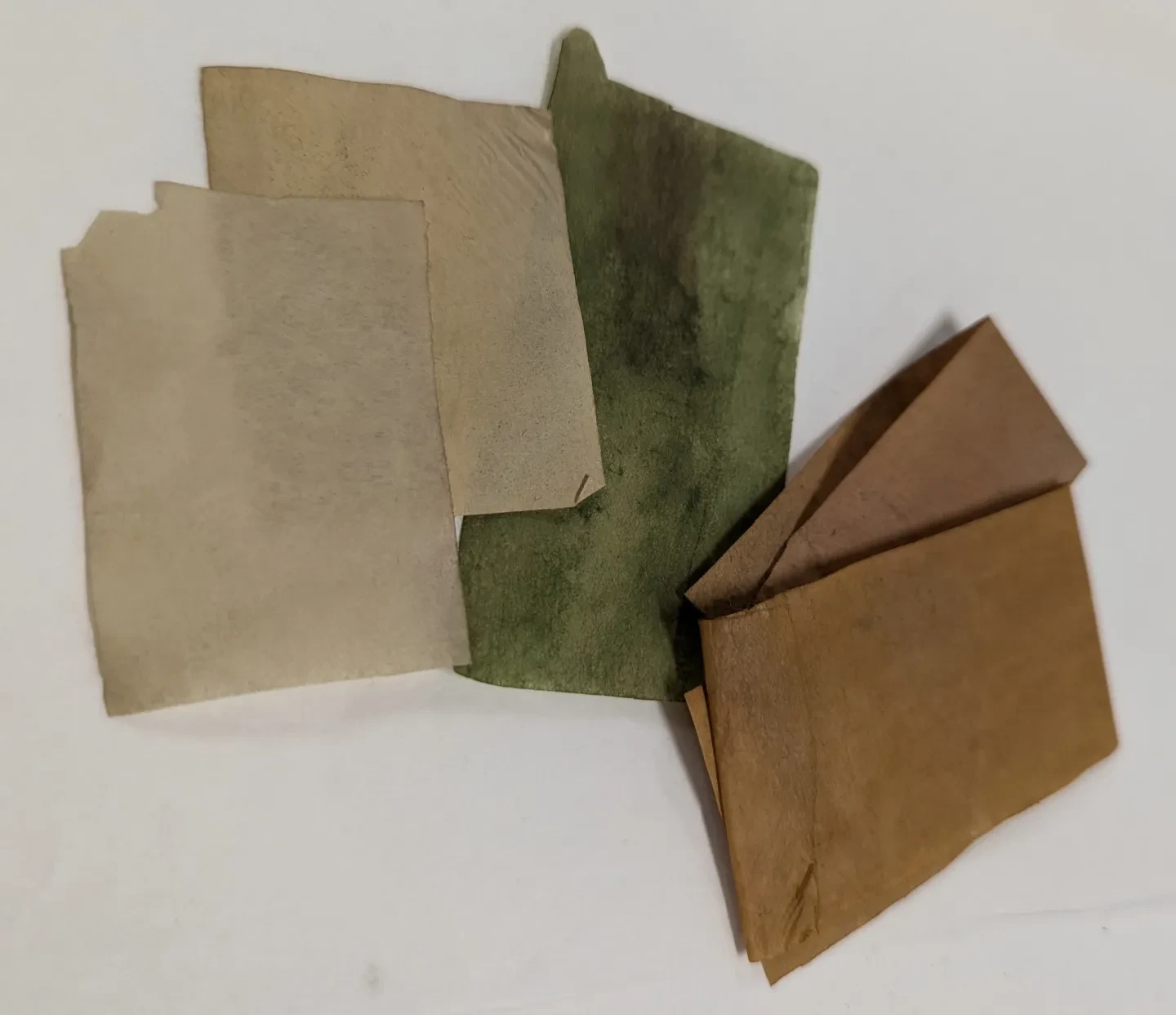

Once all the holes had been filled, the holes could be patched over with Japanese tissue paper. On the outside of the telescope, the losses were carefully traced over a clear sheet of Melinex so that patches could be cut out in the exact shape. The Japanese tissue paper was pre-toned so that the minimum amount of inpainting would be needed after application, again to reduce as far as possible the amount of moisture introduced to the telescope itself.

These patches were then adhered to the areas of loss with the same wheat starch paste used earlier.

On the inside of the telescope, the same process was used, although the patches were slightly larger and of a higher weight of paper to offer a little bit more support.

Once all the patches were in place the fills on the outside of the telescope were also inpainted so that the new areas of Japanese tissue paper would blend in with the original vellum. This ensures that the telescope can be enjoyed by visitors to the Museum for its original design, and no distraction is caused by the damage. Patching insect damage like this also means that if any further pest damage were to occur, future conservators would know the timeframe when it happened.

The result

The major goal of the treatment – to stabilise the telescope for display – was successfully met using this method.

In some areas the pest damage was so bad that the telescope had holes through both the vellum and paper layers and in many areas, it had caused the telescope tubes to become very fragile. The many tunnels and holes have been filled, patched and inpainted to disguise the damage done to the telescope.

After treatment, the telescope is much stronger and will much better withstand the transport and handling required to put it on display.

You can see the telescope on display from July 2025 until 2030 in the Tudor and Stuart Seafarers Gallery at the National Maritime Museum.