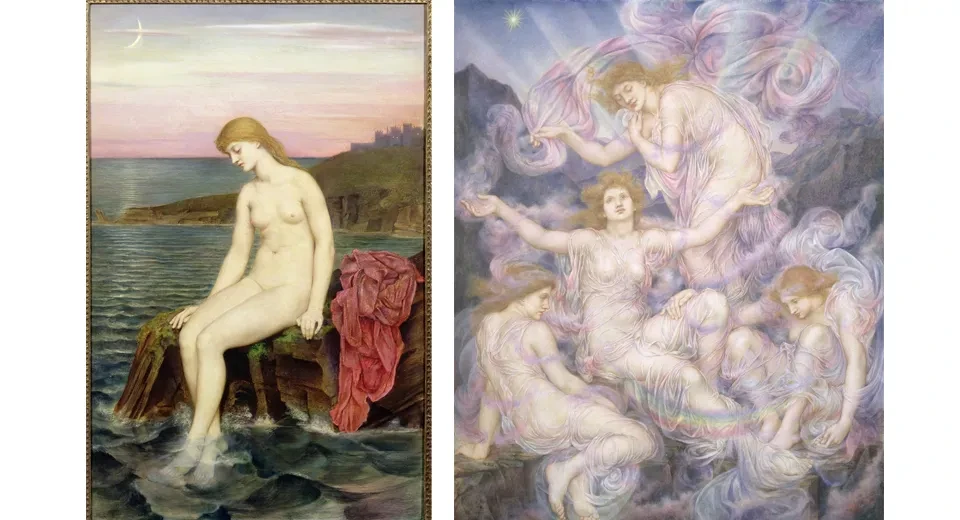

The Sea Maidens is a medium-sized oil painting (818 x 1428 mm) by Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919), completed in 1886. It is hung in the Queen's House, below a portrait of Queen Victoria (1842) by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, courtesy of the de Morgan Foundation.

As an allegorical painting influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, in particular by Edward Burne-Jones, The Sea Maidens shows five long-haired mermaids. Their tails are inside the water, while their upper bodies are outside. They affectionately hold hands, four of them almost embracing, reaching for a fifth one, slightly separated from the group. It is a delicate depiction of sisterhood; it emanates strength by boasting an iconography of femininity at its best. Moreover, even though their bosoms are nude, they do not exude any frivolous sexuality.

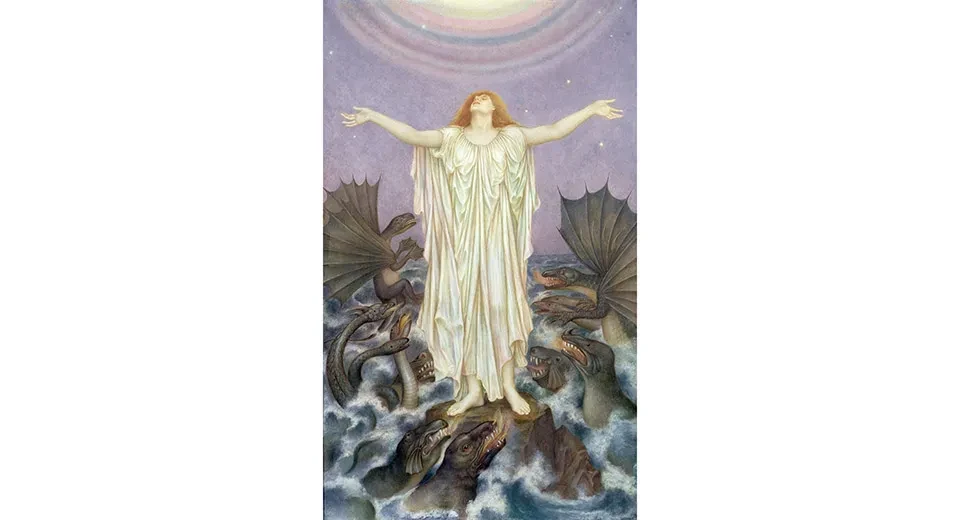

A response to Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, (1837) The Sea Maidens is the first part of a sequence of paintings. It is accompanied by The Little Sea Maid (1886-8), and Daughters of the Mist (n.d.). In this ‘trilogy’, De Morgan tackles female empowerment with reference to spiritual illumination[1], a narrative of transfiguration which aligns the feminine with the divine[2].

In Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, a 15-year-old mermaid falls in love with a handsome prince she saves after a shipwreck. In order to become human, she trades her voice for a potion that gives her legs, thus being unable to tell him of her love. He later marries someone else, and she despairs, heartbroken, wishing to return to the sea. Following the ordeal, her four sisters sell their hair in exchange for a knife, with which the little mermaid should kill the prince to retrieve her tail. She cannot bring herself to do it, jumps off a ship and drowns, her body dissolving into foam. Instead of ceasing to exist, she is turned into a spirit of light, a ‘daughter of air’.

The model for all five mermaids in The Sea Maidens was in fact a single woman, Janes Hales. De Morgan used Hales as a prototype for a number of other paintings, including Flora, Lux in Tenebris, The Dryad and Aurora Triumphans. The latter, from 1877-78, featured in Tate Britain’s 2017 exhibition Queer British Art, 1861-1967.

De Morgan mostly depicted women. In contrast to her male contemporaries, nevertheless, her subjects were athletic, imposing, awe-inspiring. She worked with bright, rich colours, which possibly symbolise an opposition to the sombre aesthetics of some of her fellow Pre-Raphaelites. In general, the mythical creatures she painted, whether goddesses, nymphs or mermaids, are not portrayed in danger, trapped and waiting to be rescued. They have ownership of themselves, not falling into archetypes of passivity, even when holding a mirror – a traditional signifier of vanity, e.g. The Toilet of Venus (1651), by Velázquez; Vanity (1485), by Memling; and Susanna and the Elders (1555-56), by Tintoretto[3].

Notwithstanding, as a suffragette, De Morgan also made clear statements against patriarchy with paintings such as Hope in a Prison of Despair (1887), and The Prisoner (1907). In The Gilded Cage (1919), a young woman looks through a window as if she yearns to be outside, dancing under the open sky and far away from her older husband, who seems bored and fairly uninterested in her. A possession in a marriage of convenience, she is literally entrapped, much like the caged bird in the left side of the image [4].

De Morgan was also a pacifist and, within her artwork, expressed her fears towards the effects of war, in particular with the onset of the Second Boer War and later with World War I, e.g. S.O.S (1914-1916), and The Red Cross (c. 1918). The construction of parables could be regarded as her method of combining anti-war messages with her broad spiritual beliefs, the same way her palette might constitute a bridge to the superconscious.

A 100 years ago, in May 1919, De Morgan passed away. And, although 2019 marks the centenary of her death, her paintings are perhaps more relevant than ever. She was a woman working as a painter in the nineteenth century. Thus, she was one of very few female artists to succeed in the 1800s, something that only a handful of women did, with names like Rosa Bonheur and Suzanne Valadon coming to mind. Additionally, De Morgan depicted women as resilient, strong subjects with their own desires, as sources of both good and evil, not categorising them as damsels in distress or mischievous witches.

Indeed, possibly much more than the Victorians, women today can grasp with the imagery of sisterhood brought by The Sea Maidens or Daughters of the Mist. The female essence, as complex and powerful as it is, is present in every last one of De Morgan’s paintings.

By Carla Valois Lobo

[1] Drawmer, L. J., 2001, p. 229.

[2] ibid, p. 196.

[3] Berger, J., 1971, p. 51; Betterton, R., 1988. P. 220

[4] Hardy, S., 2018.