Discover what to see in the night sky in January 2023, including some planets, a stand-out meteor shower and some winter asterisms.

Top 3 things to see in the night sky in January

-

Throughout the month – find the winter triangle or winter hexagon.

-

3/4 January – try to catch the peak of the Quadrantids meteor shower.

-

At the end of the month – try and catch a glimpse of a comet!

(Details given are for London and may vary for other parts of the UK)

See February 2023's night sky highlights

Look Up! Podcast

Subscribe and listen to the Royal Observatory Greenwich's podcast Look Up! As well as taking you through what to see in the night sky each month, Royal Observatory Greenwich astronomers pick a topic to talk about.

In January's episode, which you can listen to below, we talk about the latest (and last!) updates from the Insight mission on Mars, which sent its last-ever signal shortly after this podcast was recorded. We also discuss JWST's fantastic new images of Titan. At the start of January, you can join us on Twitter to vote on which news story is your favourite in our poll (@ROGAstronomers).

Our podcast is available on iTunes and SoundCloud.

Winter constellations

If you’re out to watch some fireworks on New Year's Eve, why not also look up and see if you can spot some classic winter asterisms? If you look south you should be able to spot the winter triangle or the winter hexagon.

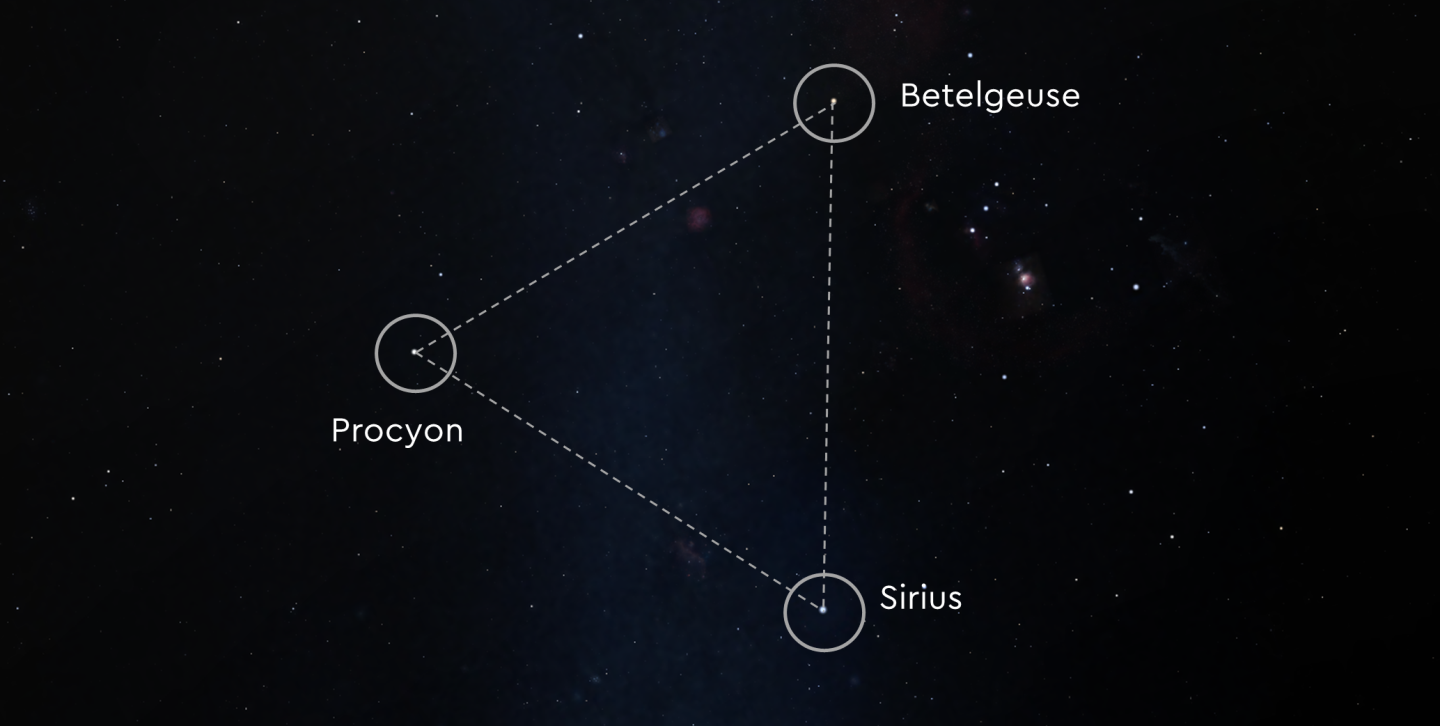

The winter triangle is made up of Betelgeuse (in Orion), Sirius (in Canis Major), and Procyon (also in Canis Minor), making a neat and almost perfect equilateral triangle. All three are bright stars, meaning this is easy to spot even in a light-polluted area.

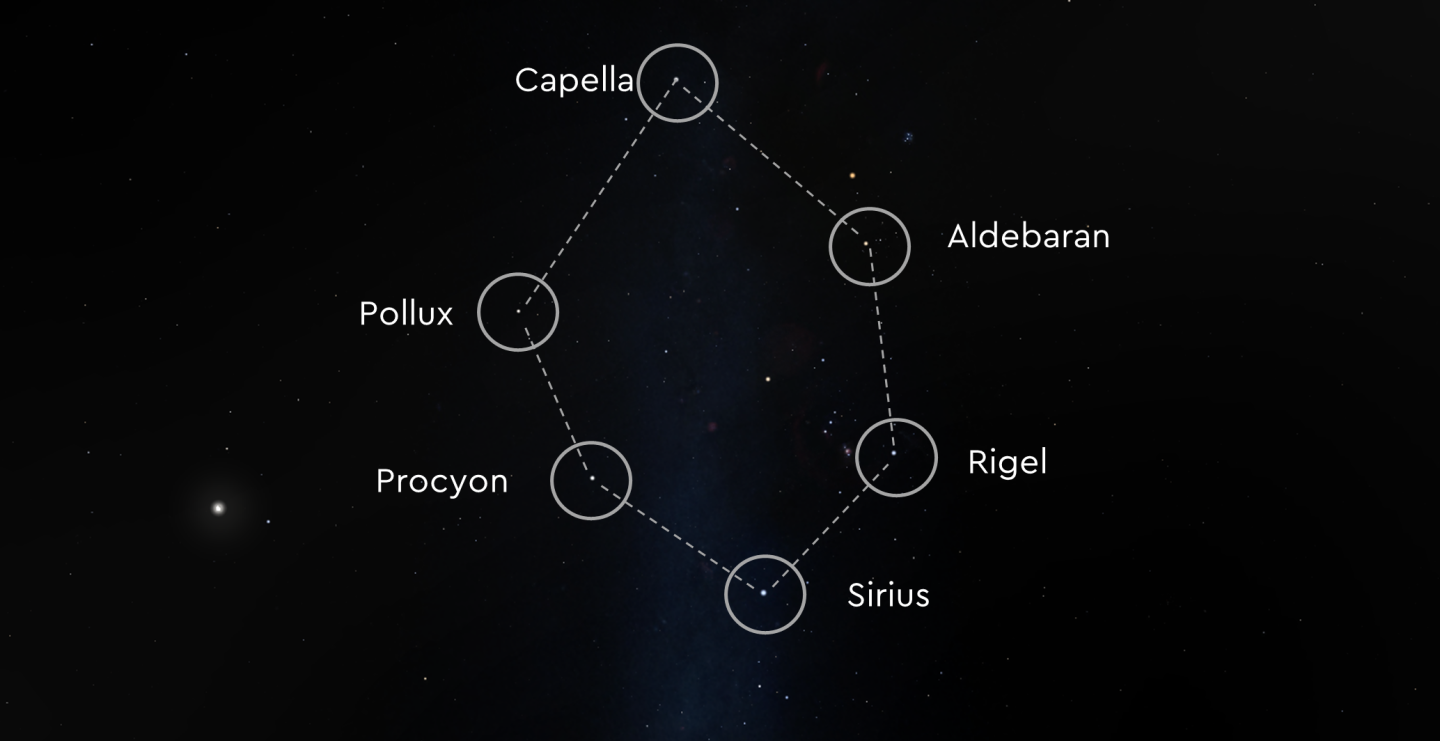

If you want to extend the geometry theme further, you could also find the 6 bright stars from 6 different constellations that make up the winter hexagon. The stars in this asterism are Sirius and Procyon, along with Rigel (in Orion), Aldebaran (Taurus), Capella (Auriga) and Pollux (Gemini).

Amongst these stars Rigel, as a blue supergiant, and Aldebaran, as a red giant, will be differentiated by their colours. Let your eyes adjust to the darkness, have a careful look and see if you can appreciate the blueish colour of Rigel compared to the red/orange of Aldebaran.

Spot some planets

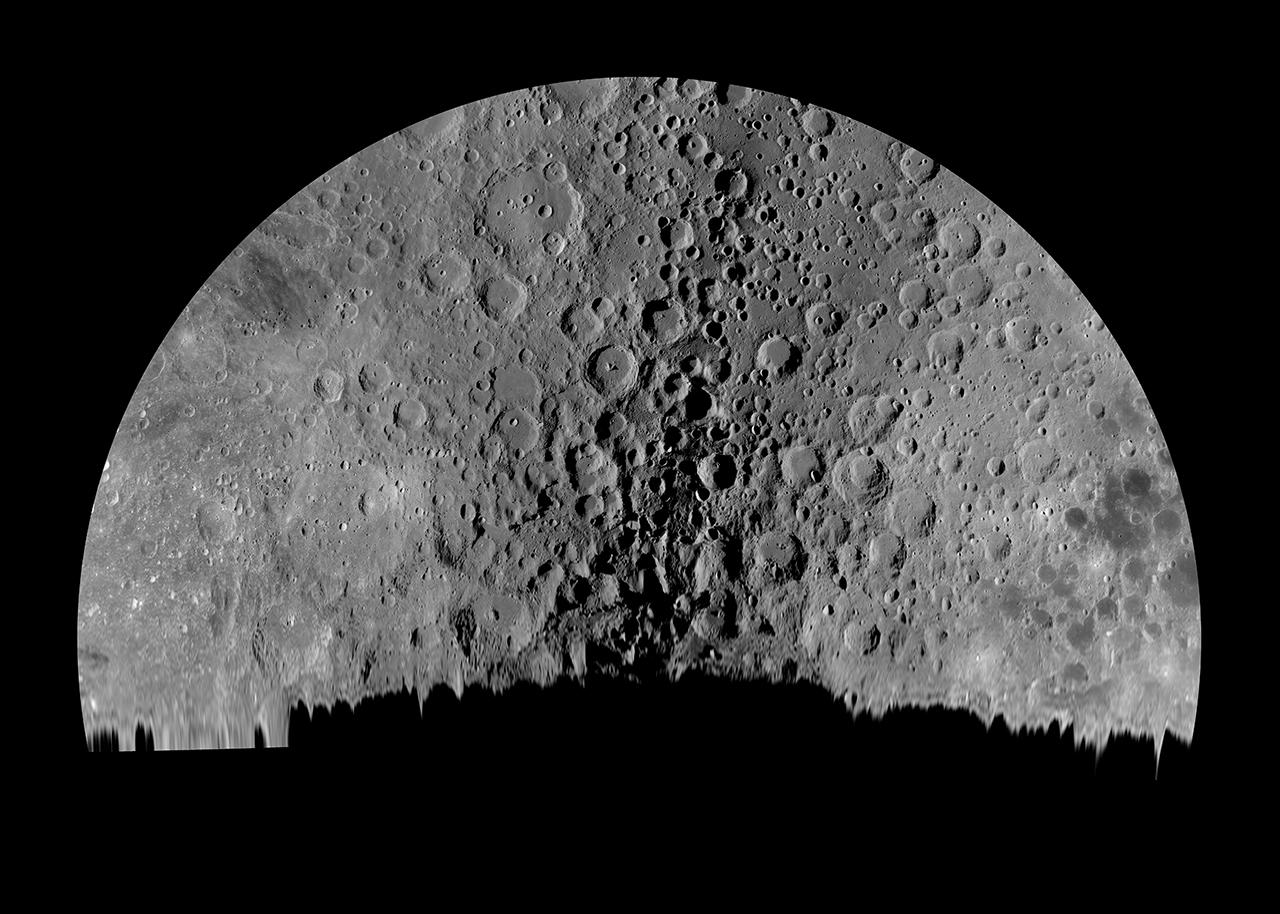

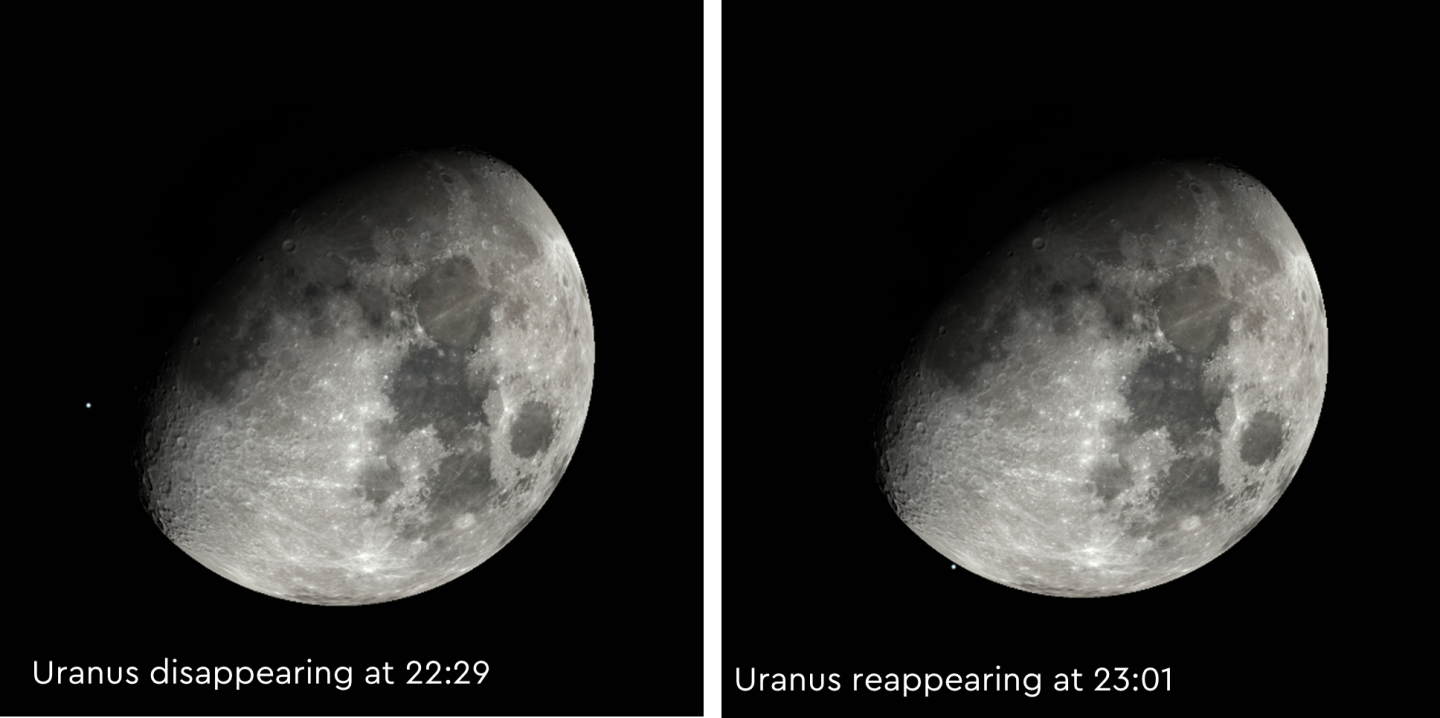

It continues to be a great time of year for planet hunting. If you missed the lunar occultations in December we have another one on 1 January, with Uranus once again appearing to pass behind the Moon’s face. Depending on your location within the UK, your view and the exact timings of the event will vary.

Here in Greenwich the Moon will just brush past Uranus, but further north in the UK you’ll either see a grazing occultation or a full occultation with the lunar disc entirely blocking the planet. For example, if you live in Manchester, or anywhere in the UK with a similar latitude, Uranus will start to disappear around 22:29 and reappear at 23:01.

Uranus will keep on orbiting the Sun in its usual 84-year trek, but if you want to track it throughout the month towards the end of January it will appear to reverse its direction across the sky. Uranus has been in retrograde, but from 28 January will move to prograde motion once again.

This is because the Earth completes an orbit of the Sun much more quickly than Uranus, so we effectively ‘overtake’ Uranus and it sometimes looks to us like it’s moving backwards - when it definitely isn’t!

Mars reached opposition on 8 December and will now be fading throughout the month, but still visible in the sky and a lovely target for observation.

And finally, the Earth itself will reach perihelion (its closest point to the Sun in its orbit) on 4 January. On this date we will only be 147 million km away from the Sun. It won’t make a difference to our weather, but maybe the thought of our star close at hand will keep you warm whilst stargazing during the cold January nights!

Southern Hemisphere

Of course, if you’re in the southern hemisphere you’ll be enjoying the summer weather! One summer constellation you could focus on this month is Canis Major, the great dog.

The brightest star in Canis Major, and in fact the brightest star in the whole night sky, is Sirius. Sirius appears bright as it’s close to the Earth, only around 8 and a half light years away. Throughout the summer Canis Major will be high in the night sky for the southern hemisphere.

If you want more of a challenge than Sirius, try looking for M41, known as the little beehive cluster, also found within this constellation. If you’ve found Sirius, look four degrees south to spot this beautiful collection of young stars which contains around 100 members, and covers an area of sky about the size of the Full Moon.

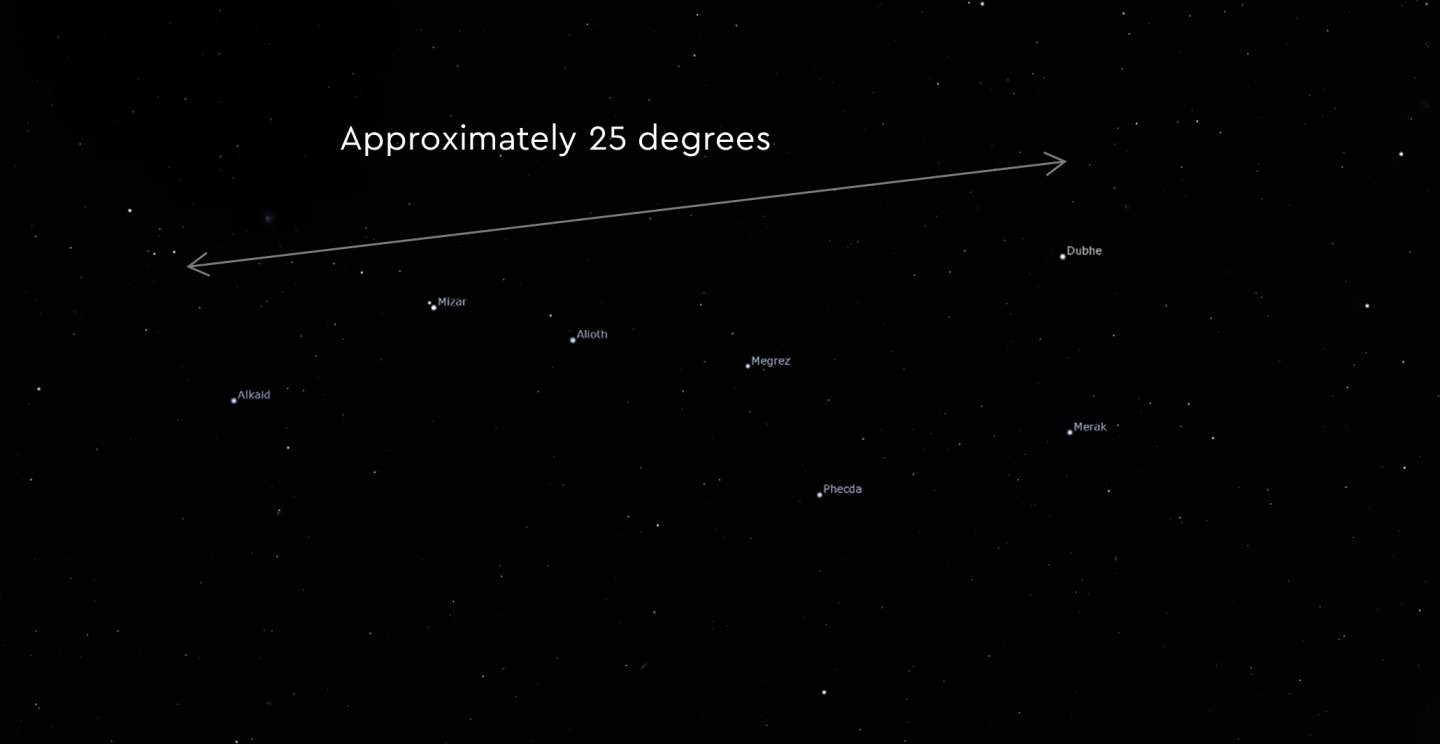

Determining Distances

If you’re trying to determine angles across the night sky, try stretching out your hand so it is at arm's length away from you. Your little finger is about 1 degree in width, and if you spread out your fingers wide, from your little finger to your thumb is around 25 degrees across.

You could also use features you know in the night sky – for example for northern hemisphere stargazers the plough is also around 25 degrees across!

Quadrantid meteor shower

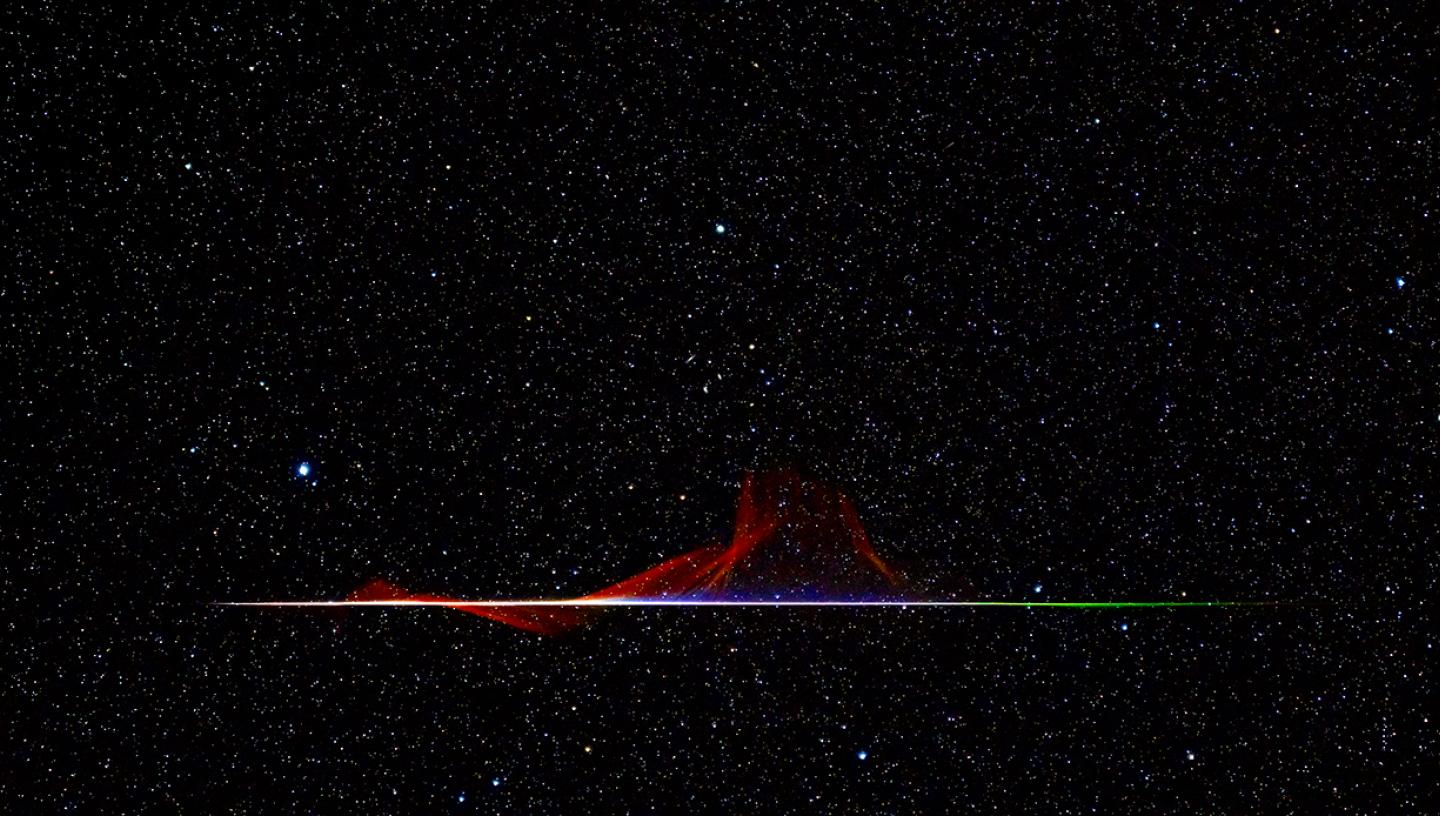

The Quadrantids meteor shower extends from 28 December to 12 January, but it peaks on the night of 3 and 4 January. It can be a fantastic firework display of its own, with showers sometimes peaking at 110 meteors per hour. The Quadrantids are also unusual for a number of reasons.

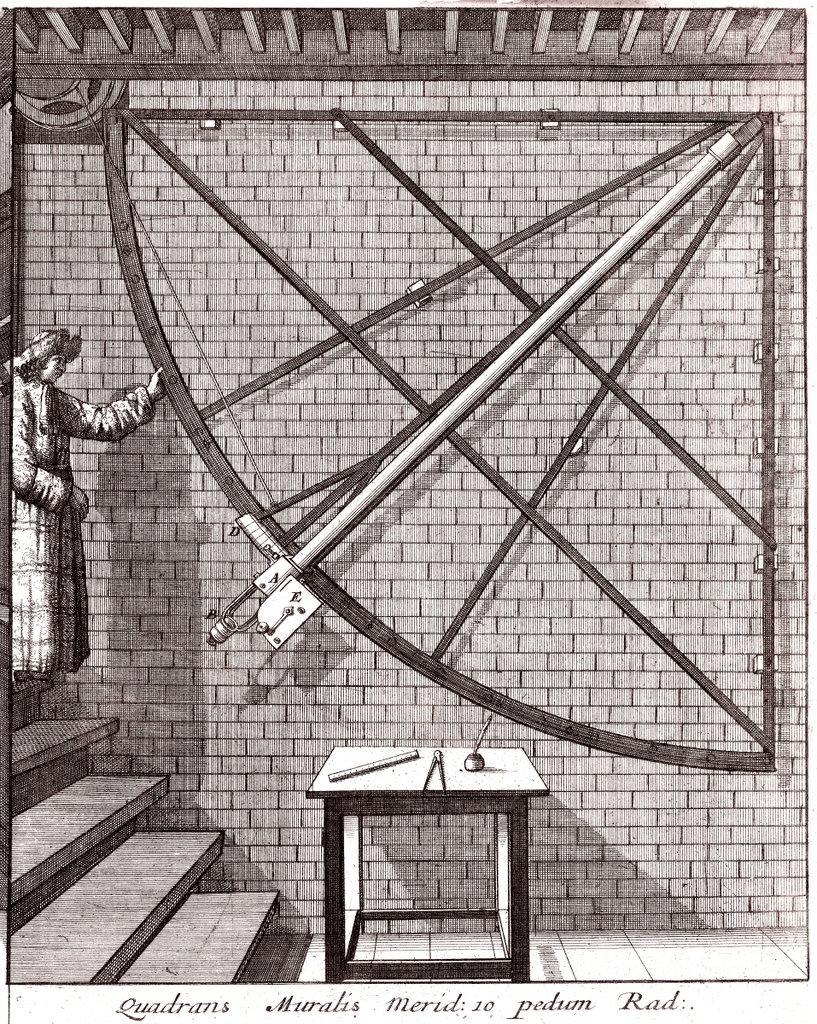

Meteor showers are usually named after the area of the sky they appear to originate from – for example the Leonids originate in Leo, and the Orionids in Orion. The Quadrantids are named after Quadrans Muralis, which is a constellation that no longer exists. Quadrans Muralis is Latin for Mural Quadrant.

This was first described in 1795 but omitted from the ‘official’ list of constellations that was set by the International Astronomical Union in the 1920s. Nowadays if you want to find the origin of the Quadrantids you’ll have to look within the constellation of Boötes, not far from the Big Dipper.

This shower is not only interesting in being named after a now non-existent constellation, but the origin of the shower is also unusual. Most meteor showers are caused by comet debris, but it’s been suggested that this shower comes from asteroid 2003 EH1.

Meteors happen as the Earth encounters a ‘stream’ of particles which heat up and glow as they speed through our atmosphere. The stream of particles which causes the Quadrantids is unusually narrow, meaning that the peak of this shower is surprisingly short, sometimes only a few hours on a single night. This, combined with the light from the waning gibbous Moon on 3 and 4 January, is going to make spotting these shooting stars more of a challenge. If you do see any, let us know!

Comets

Keen sky watchers might remember the appearance of comet Neowise in our skies back in the summer of 2020. There’s a possibility of another comet appearance this January, with the somewhat less catchily named C/2022 E3 (ZTF) approaching us this month. This comet was discovered in March 2022 by the Zwicky Transient Facility, which regularly scans the sky and compares the images to spot anything that has changed - for example supernovae, variable stars, or approaching comets!

C/2022 E3 (ZTF) is coming into the inner Solar System, towards the Sun. It will be at its closest approach to the Sun on the 12 January, and then at its closest approach to the Earth on 1 February (at this point it’s still over 40 million km away!)

C/2022 E3 (ZTF) is already bright enough to be visible through a telescope, and it will be getting brighter throughout the month. Images taken so far showcase its eery green glow, a product of UV radiation from the Sun illuminating the gases sublimating from the comet’s surface. At its brightest in our skies this comet still probably won’t be as impressive as comet Neowise, and you’ll need a very dark sky to spot it.

However brightness estimates vary, and comet viewing is always unpredictable - some think it could be visible to the naked eye! This would mean it has a magnitude of around +6, about the absolute limit the human eye can see. Even if it’s only visible with binoculars or a telescope, you should definitely get out and try and spot it if you can. As this is a long-period comet with a 50,000-year orbit, this is your only chance to catch it!

How to see Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF)

And as always if you take any pictures of the night sky you can share them with us @ROGAstronomers.

The Moon's phases this month

Full Moon – 6 January (23:08)

Last Quarter – 15 January (02:10)

New Moon – 21 January (20:53)

First Quarter – 28 January (15:19)

If you're a fan of the Moon, then see the winners and shortlisted images in the 'Our Moon' category of the 2022 Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition.

Stargazing Tips

- When looking at faint objects such as stars, nebulae, the Milky Way and other galaxies it is important to allow your eyes to adapt to the dark so that you can achieve better night vision.

- Allow 15 minutes for your eyes to become sensitive in the dark and remember not to look at your mobile phone or any other bright device when stargazing.

- If you're using a star app on your phone, switch on the red night vision mode.

Never miss a shooting star

Be the first to hear space and astronomy news from the Royal Observatory Greenwich. Sign up to our space newsletter now.

Planetarium Shows

Join us for live planetarium shows