Paintings conservation can often feel like detective work, analysing tiny flecks of paint to uncover the artist's tools and techniques. But what has our team learned during the conservation of A Royal Visit to the Fleet?

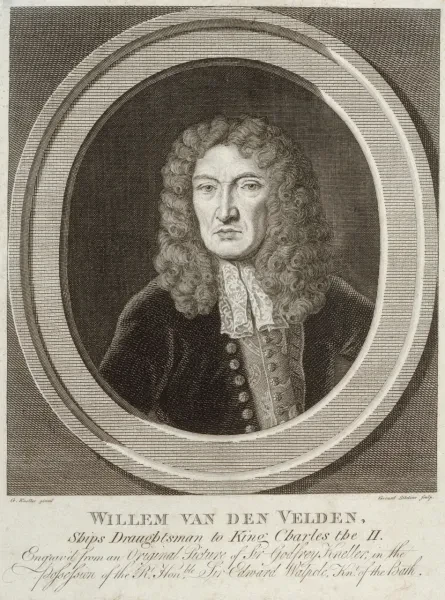

When we first entered the paintings conservation studio for our internship at the Prince Philip Maritime Collection Centre, we were greeted by the grand painting of A Royal Visit to the Fleet in the Thames Estuary by Willem Van de Velde The Younger (1633-1707).

The painting was begun in 1674, shortly after the father and son team, the artists Van de Velde the Elder and Younger, arrived in England and were given a studio in the Queen's House by Charles II.

The Royal Visit is currently part of an extensive conservation project, and the centrepiece of Conservation in Action at the Queen’s House. Here, visitors can witness the painting being conserved and ask questions about the painting and the conservation process.

It's been fascinating to watch how visitors respond to the work, and to try and answer the intriguing questions that they raise.

So, what do we know about how Willem van de Velde worked?

An expensive commission? What the canvas tells us

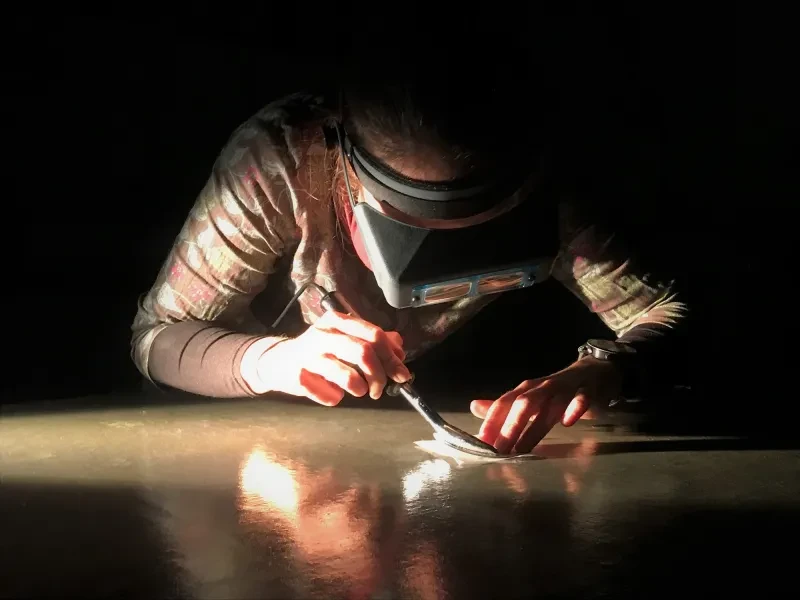

Much of what we know about the precise materials and techniques of this painting is thanks to the work of Kendall Francis (pictured), a Courtauld Institute of Art student who did a thorough technical study of the work in 2019 prior to its conservation treatment.

She used a variety of methods to examine the structure of the painting, as well as a number of other paintings in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection by both Van de Velde the Elder and Younger.

One of the first things Francis noticed about the Royal Visit was the unusual twill weave canvas support.

Ordinarily, the Van de Veldes' studio used what's known as 'tabby weave' canvas supports throughout their English period. Although Francis couldn’t see the back of the original canvas during her initial investigation, she did notice something unusual about it on the front.

A small area of missing paint on the top edge revealed a striped indigo line, suggesting the canvas was made out of 'ticking fabric', a material typically used for making beds.

Her suspicions were later confirmed when the old lining canvas was removed and replaced as part of the conservation process. The reverse of the original canvas was found to have a distinctive set of horizontal dark indigo lines, typical of bed ticking.

A canvas of this type and size would have enabled the artist to avoid having a conspicuous seam through the middle of the painting. It would have cost a huge amount to import the material to England though, a fact that perhaps reflects the importance of the commission.

Paints and processes - analysing how van de Velde worked

Francis also discovered something slightly unusual about the painting's preparation layers.

In order to understand these, she took tiny flakes of paint, embedded them in resin, ground down one side and then looked at them in cross-section through a microscope.

The first two layers of priming she found were not especially surprising. They consisted of a red-brown layer followed by a light grey. Such double ground layers were fairly typical of primings in 17th century London, and were probably prepared commercially away from the studio.

The third layer was more unusual, even for van de Velde. It had much larger pigment particles, suggesting it was prepared and applied in the artist's studio, and was a very dark grey-black colour. Francis suggested that the unusual dark tone was perhaps intended to contribute to the brooding, triumphal mood we see in the picture.

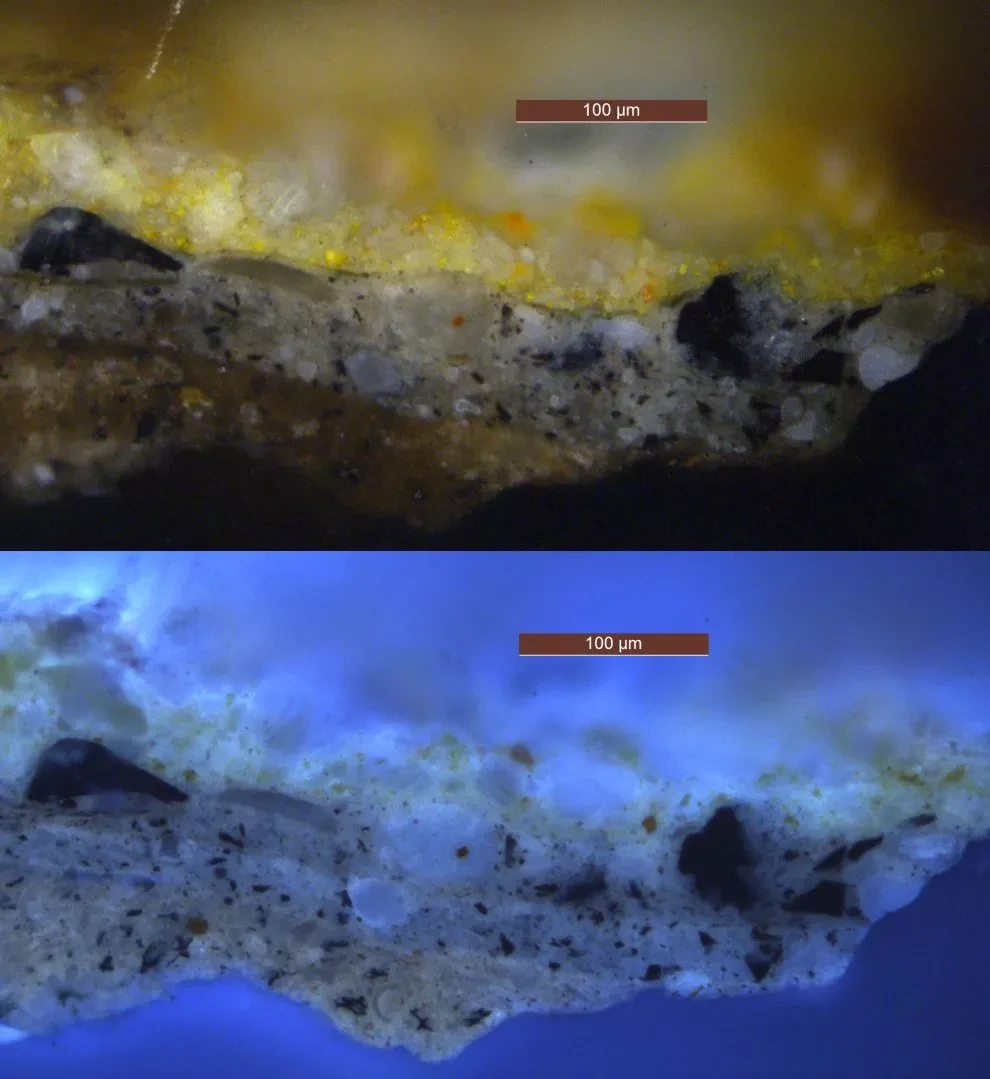

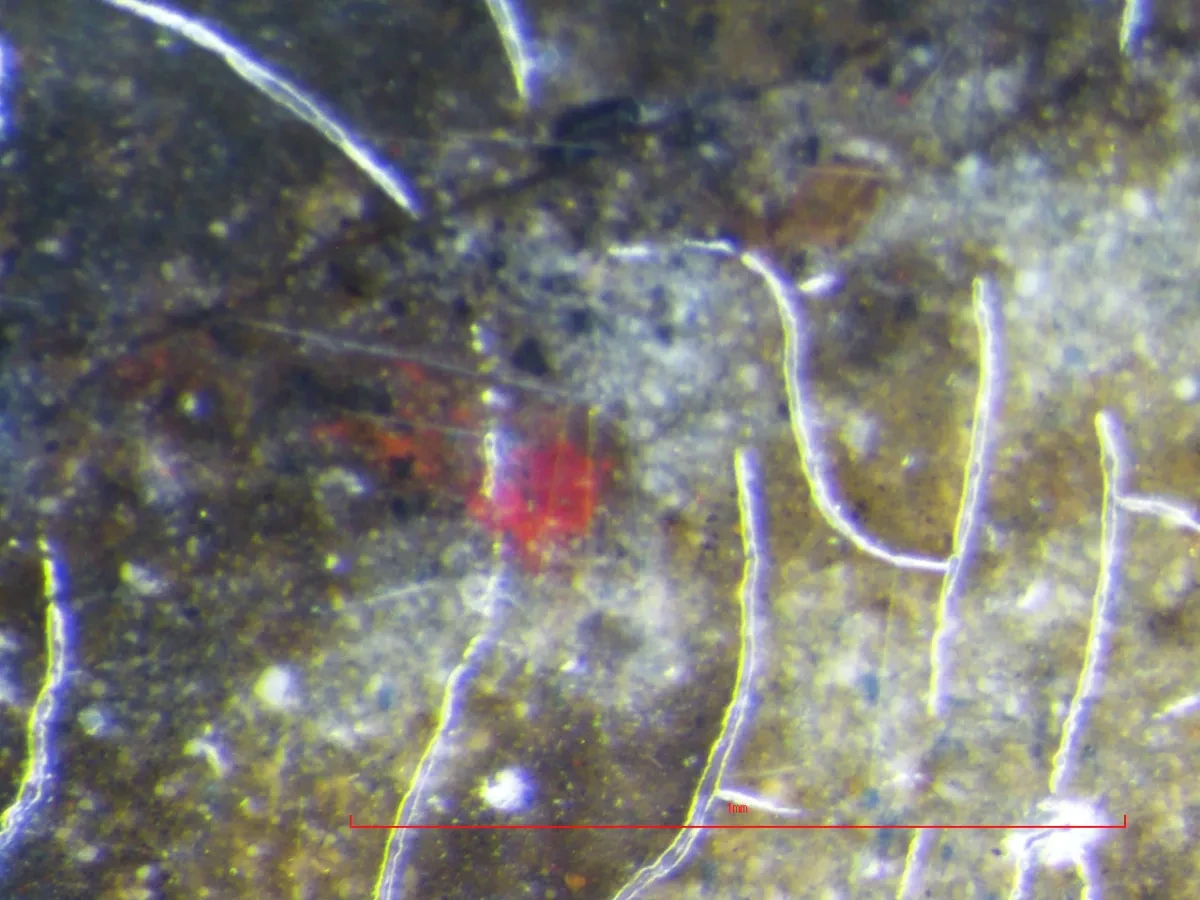

Cross-section of paint taken from the gilded stern of the Katherine yacht that appears in the Royal Visit painting.

The top half of the photo shows the paint in normal light, and the bottom section under ultraviolet (UV) light.

We can see three preparation layers under the yellow paint layer. The first is a red-brown, followed by a grey layer consisting of small black and white pigment particles. These were probably commercially applied.

There is then an upper grey layer containing much larger black pigment particles, which was probably applied in van de Velde’s studio.

The pigment particles in the yellow paint layer were found to contain the element arsenic, indicating the presence of the rare pigment orpiment.

This use of such a dark ground layer affected the medium that van de Velde could subsequently use to create what is known as the underdrawing.

Underdrawings help to sketch out the composition, and are made in advance before the artist begins painting.

On van de Velde's lighter coloured paintings, Francis worked out that the artist tended to use a fluid brown medium.

Although this medium didn’t show up on images taken with an infrared camera (the normal way that conservators look at underdrawings), it could occasionally be seen through gaps in the paint.

However, this fluid medium couldn't have been used on the distinctive, dark priming of the Royal Visit: the underdrawing simply wouldn't have shown up. So, what was used instead?

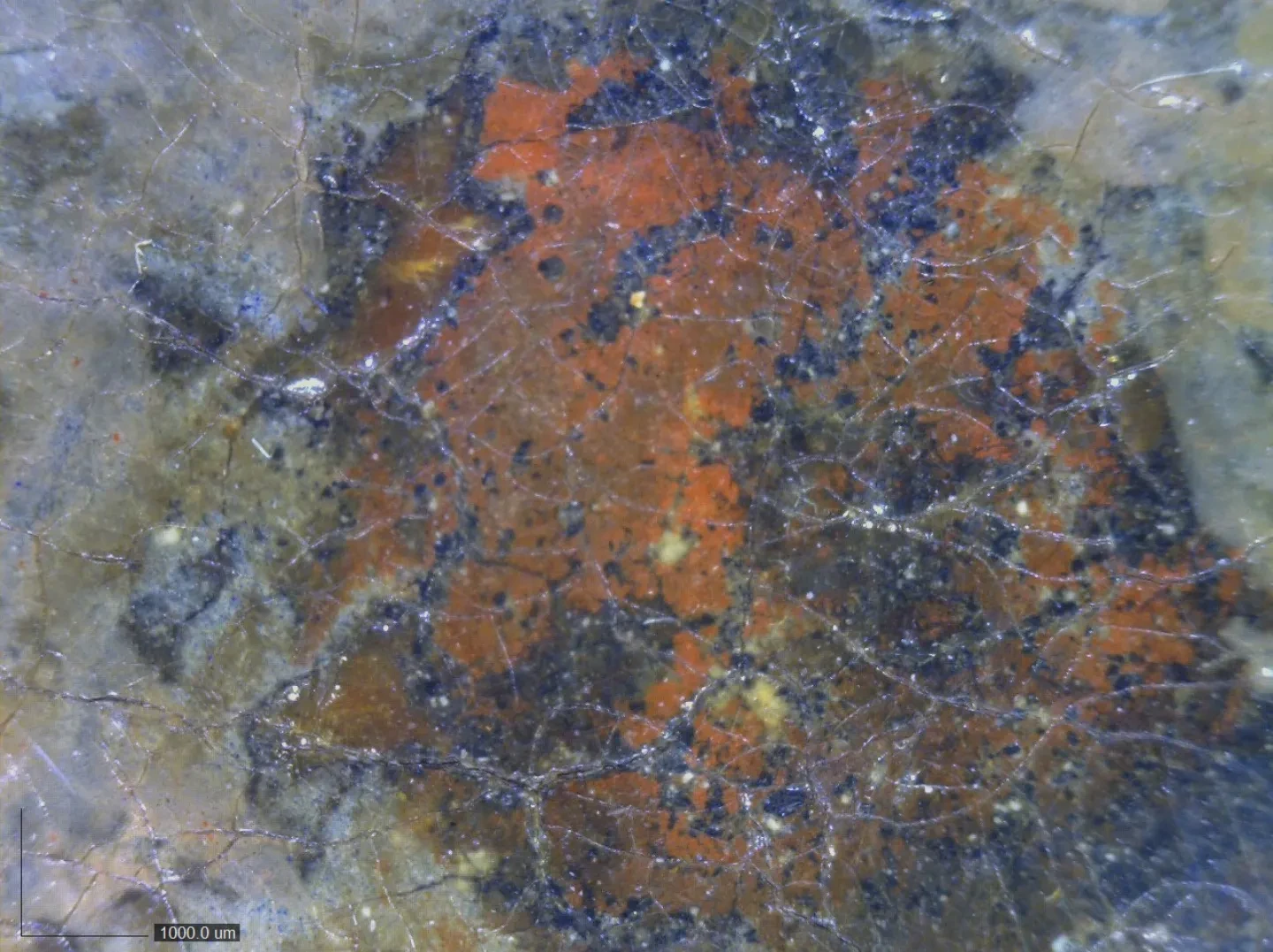

Under the microscope, Francis noticed a few bright red spots (pictured), which suggested a red chalk-based underdrawing. Indeed, when she took samples and looked at them in cross-section, she saw a bright red layer directly beneath the paint which must have been the underdrawing.

Further analysis of the chemical elements and compounds in this layer suggested that it was red chalk mixed with an organic wash called bistre (a brownish water soluble pigment mixed with water). The chalk would have enabled the underdrawing to show over the dark ground, while the bistre would have fixed it in place and prevented it from being disturbed during the painting process.

A toxic business - the use of arsenic in paint

After establishing the underdrawing in the Royal Visit, van de Velde the Younger was ready to begin painting.

Close examination of the paint surface reveals that he began with the sky, leaving space for the flags, sails and precise outlines of the ships, including many of the smaller, intricate elements.

This indicates that he had a clear plan for the painting in advance, and could have allowed assistants to paint certain simpler elements whilst still retaining control of the more complex areas and overall composition.

Francis was able to study the pigments within the painting through a method known as Energy Dispersive X-ray analysis. This allowed her to identify the particular chemical elements present in the paint.

For the most part, it seems van de Velde used a typical 17th-century Dutch palette consisting of lead white, iron earth colours, umbers, vermillion, smalt, azurite and bone and charcoal black.

There was one quite unusual finding though. Traces of the toxic element arsenic were found in the golden yellow highlights of the Katherine yacht (pictured), suggesting the pigment orpiment.

Orpiment was known to be used amongst Venetian artists of the time, yet its use in English paintings is seldom noted.

Cornelius Johnson (1593-1661), an English-born Dutch artist, mentioned its use to imitate gold paint. Van de Velde appears to have used it in the thickly painted, gold-like highlights to give the scene a sense of luxury and supremacy.

Francis's technical analysis and observations have provided our conservators with new insights into Van de Velde’s innovative approach in producing the Royal Visit.

Although some of the materials and techniques are conventional for 17th century Dutch and English painting, the analysis showed how the artist adapted and exploited these conventions to create the final work.

When Conservation in Action at the Queen's House ends, both paintings conservators Sarah Maisey and Miranda Brain will continue the retouching process in the conservation studio. Our time in the Queen's House however has been tremendously engaging and educational. We hope visitors too have enjoyed this microscopic investigation into Willem van de Velde's work.

This article was written by Andrei Azzopardi and Zuraida Akma, who will shortly be completing their MA in easel paintings qualifications at Northumbria University.