In this month’s blog we travel to Japan, more precisely to its northernmost island of Hokkaido, and through a journal kept in 1871 by Lieutenant Swinton Colthurst Holland, meet the local Ainu people.

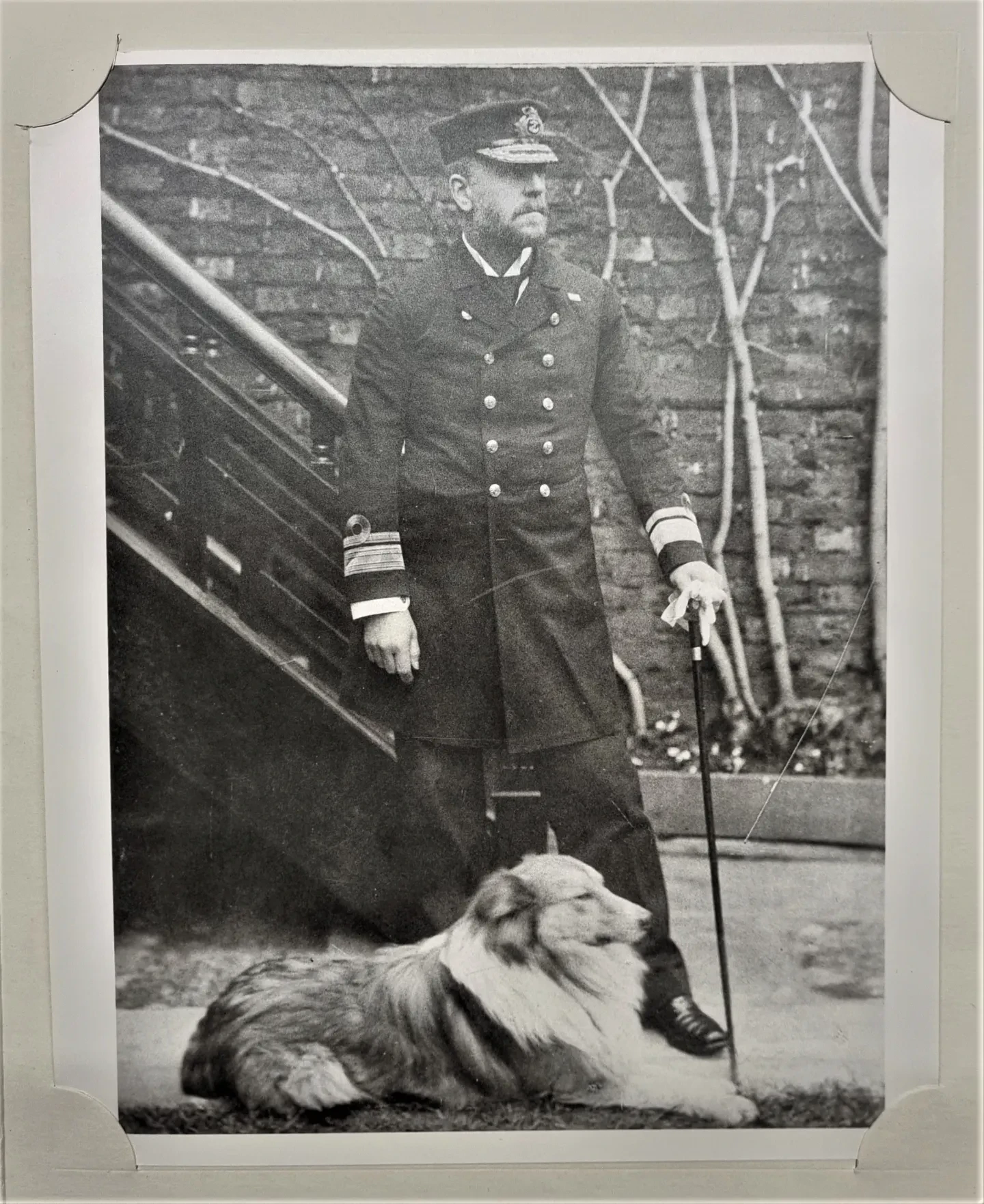

A life in the Royal Navy

Born on 8 February 1844 in Dumbleton, Gloucestershire, Swinton Colthurst Holland joined the Royal Navy in 1857 at only thirteen years old. During his naval career he was stationed around the world, and kept notes of his experiences and thoughts in personal journals and diaries. The Caird Library and Archive holds some of these journals covering the years 1858 to 1893 (HND/101/1-6).

Although there are certainly many stories to be uncovered in these journals, the one that caught my eye relates to his service on HMS Sylvia (RMG reference: HND/101/5) and her circumnavigation of Hokkaido (formerly known as Yezo/Yesso or Ezo, or Ainu Moshir in the Ainu language).

Surveying East Asian waters on HMS Sylvia

HMS Sylvia was a wooden screw gun vessel designed and built for the Royal Navy specifically as a survey ship. After her launch in March 1866, she was commissioned for service on the China Station and under command of Edward Wolfe Brooker conducted survey work in Chinese and Japanese waters.

By early 1868 – not least due to growing Western influence and aggression – Japan was reopening its borders after over 250 years of foreign isolation and had started to go through rapid socio-political changes. The same year, HMS Sylvia replaced the Serpent as the main surveying ship in the region and over the next three years would survey the Japanese coast and Seto Inland Sea (Seto Naikai), to establish new, safer sea routes for the ever-growing fleets of Western and local trade and naval ships.

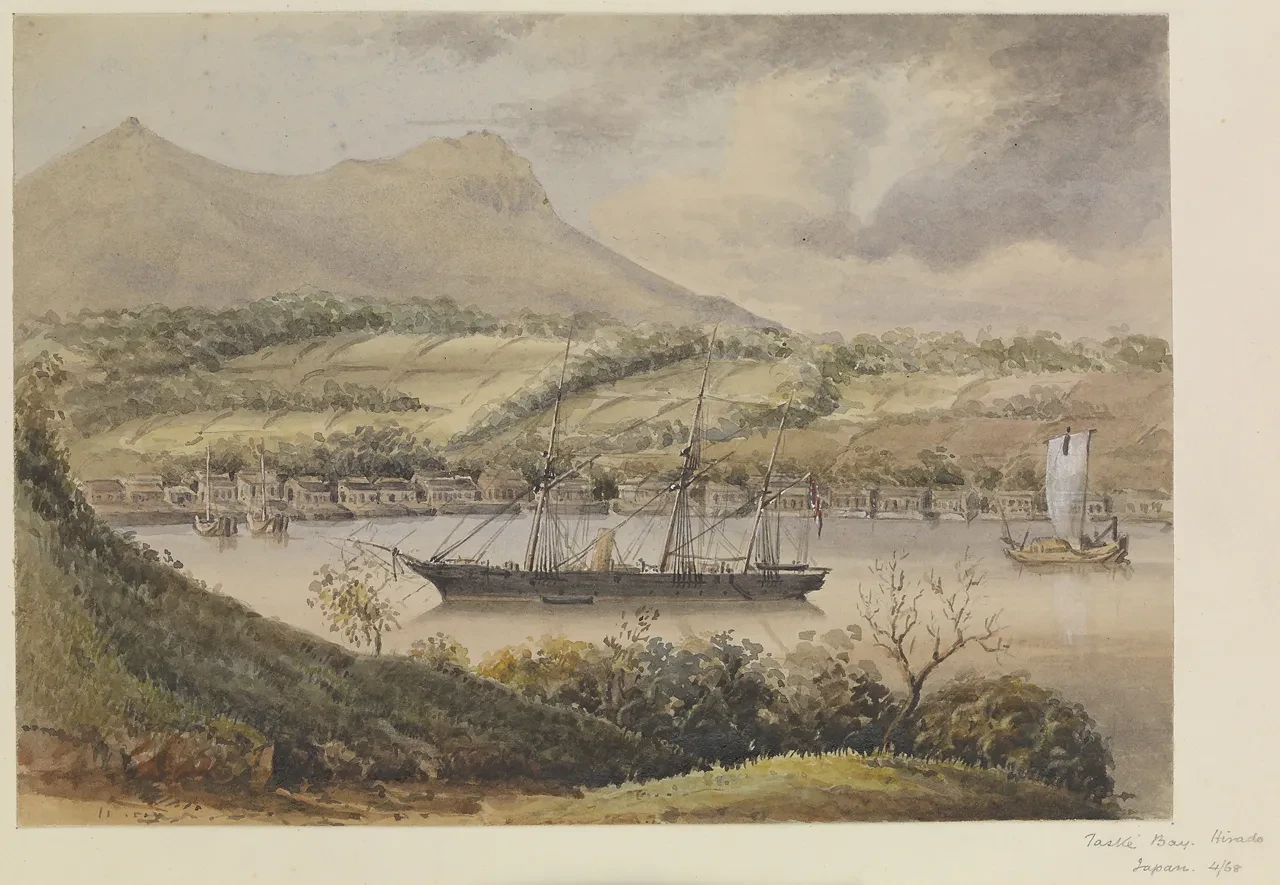

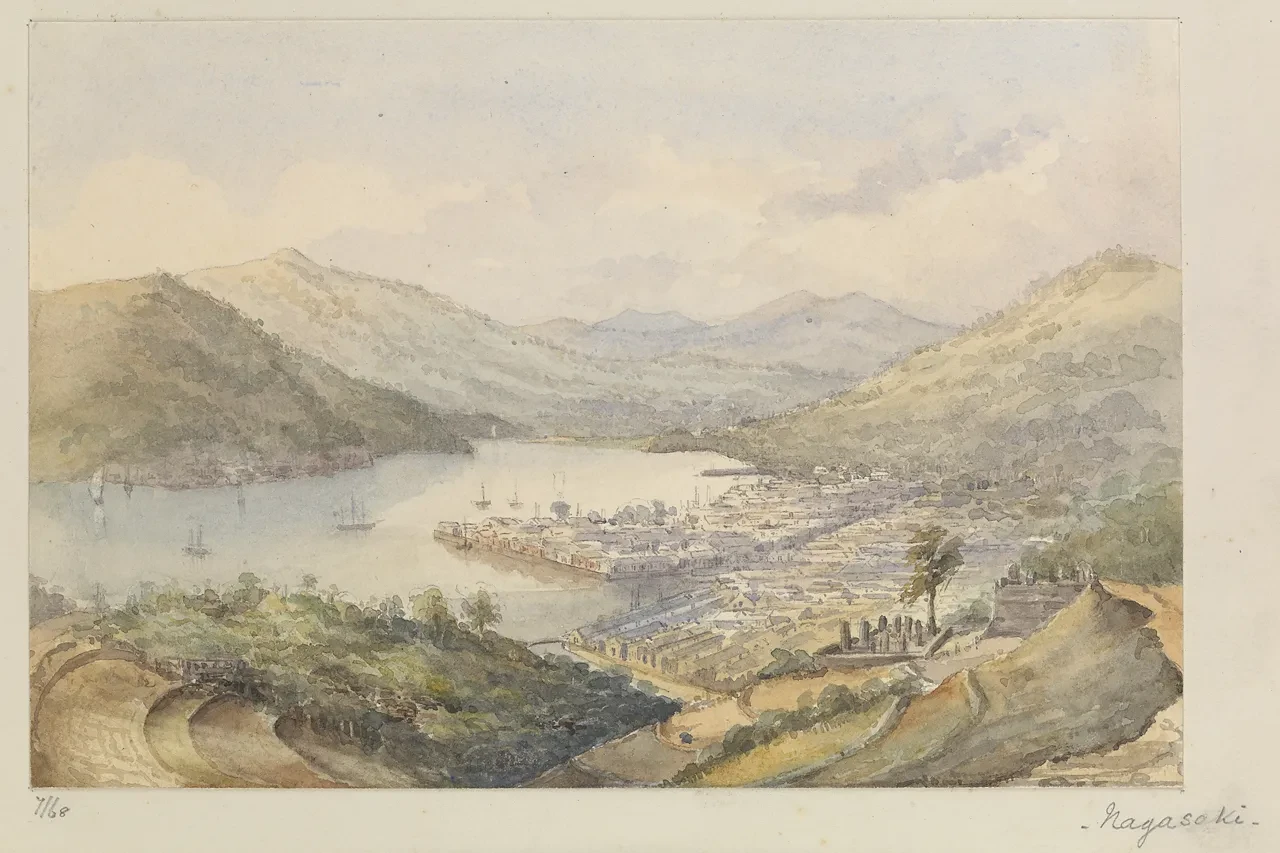

During these early years, then-lieutenant and second-in-command of HMS Sylvia James Henry Butt recorded his impressions of the country and its people in a memoir (BRG/53/1) and watercolour paintings (PAJ2050), some of which are held at the National Maritime Museum.

After some repairs carried out in Hong Kong in 1870, HMS Sylvia returned to Japan – this time under the command of new captain Henry Craven St John, and a new crew including the young lieutenant Swinton Colthurst Holland.

Off ‘to the almost unknown region of the Island of Yesso’

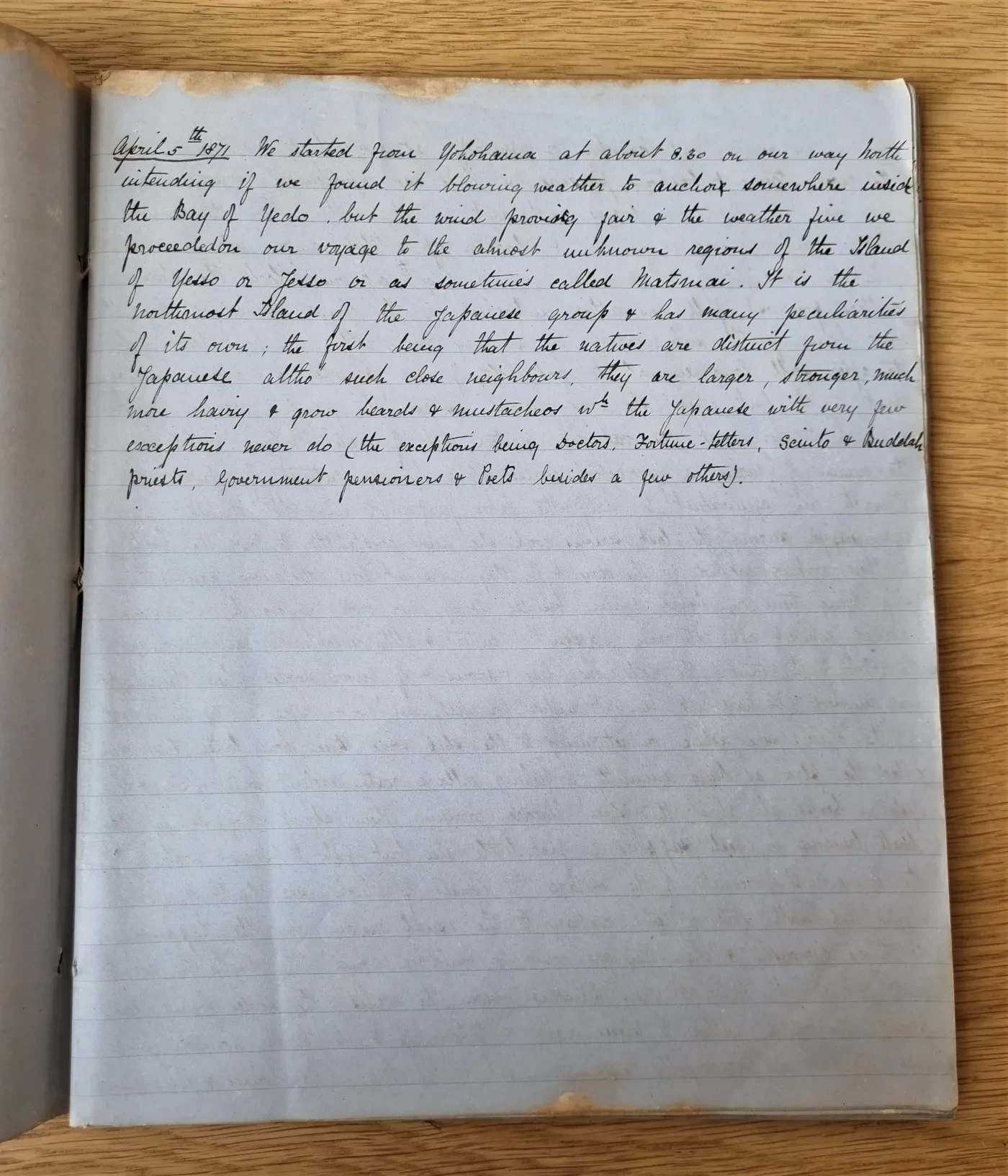

In spring of 1871, after more surveying work in the Seto Inland Sea, HMS Sylvia accompanied by the Japanese vessel Kasugamaru set off to survey and circumnavigate ‘the almost unknown region of the Island of Yesso’. The island and its locals had only just been annexed in 1868, and the Japanese themselves had yet to fully explore and survey their newly acquired lands, waters, and citizens.

The voyage was early on plagued by bad weather. With strong headwinds slowing them down, it took the steamer nearly a week after setting off from Yokohama on 5 April 1871 to reach the northernmost tip of the Japanese main island, Honshu, and soon after, their designated goal.

Surveying Hokkaido

The crew would spend the next weeks up and down the eastern coast of Hokkaido, visiting the city of Hakodate and other smaller ports and villages along the way. Although already well into spring, they were surprised by the rather cold temperatures and stormy weather, and their work often stalled due to squalls of wind, rain, and even snowfall.

On 24 May Holland wrote in his journal:

Today we crossed over to Kunashir island, we had previously seen some frozen snow on the horizon & passed a small quantity but we were none of us prepared for the sight of such an extent of sea literally covered with large masses of ice, it extended along the sea in the direction of the NE Cape of Yezo as far as the eye could meet & even from our bridge a height of at least 12 feet it appeared as an unbroken sheet. The highest of the humps stood about 5 feet out of the water & their various shapes & forms were sprinkled in most picturesque groups over the flats.

Only by the end of June did the weather finally clear up and revealed the true beauty of the island.

Thursday June 22nd

[When] the sun came out we found we were anchored in a most beautiful little Harbour round the ship were hills covered with verdure & trees of a most lovely green, there was no great contrast of shade only enough to prevent the eye getting weary of monotony & every here & there were slopes partially covered with trees the remainder looking as though it were grass & which were compared by all who had any idea of enjoyment of scenery to well kept parks in England.

Saturday July 8th

The country round here is very beautiful, the verdure being most varied & luxuriant & wild flowers plentiful. The wood scenery is also most likely some of the prettiest views being the glimpses of glens with streams running through them.

Passing their free time

Apart from determining salient points and surveying the coastline and harbours, the crew seemed to have had a fair amount of free time, as Holland regularly mentions hiking and hunting trips deeper into the dense forests and mountains of the island.

By his own admission, Holland might not have been the best shot and in any case seemed more interested in hiking, photography and the local Ainu people. He writes about attempts to photograph the ship and the landscape as well as the often reluctant locals, but also seems interested in the Ainu’s culture and way of life.

While his photographs, unfortunately, have not made it into the Caird Library and Archive’s collection, Holland’s journal gives us glimpses of how he perceived and interacted with the Ainu as well as the Japanese. Rather than focusing on their official naval work in Hokkaido, Holland writes about encounters and stories he heard from their Japanese interpreters and guides, and tries to question the Ainu themselves about their customs and practices.

The Ainu of Hokkaido

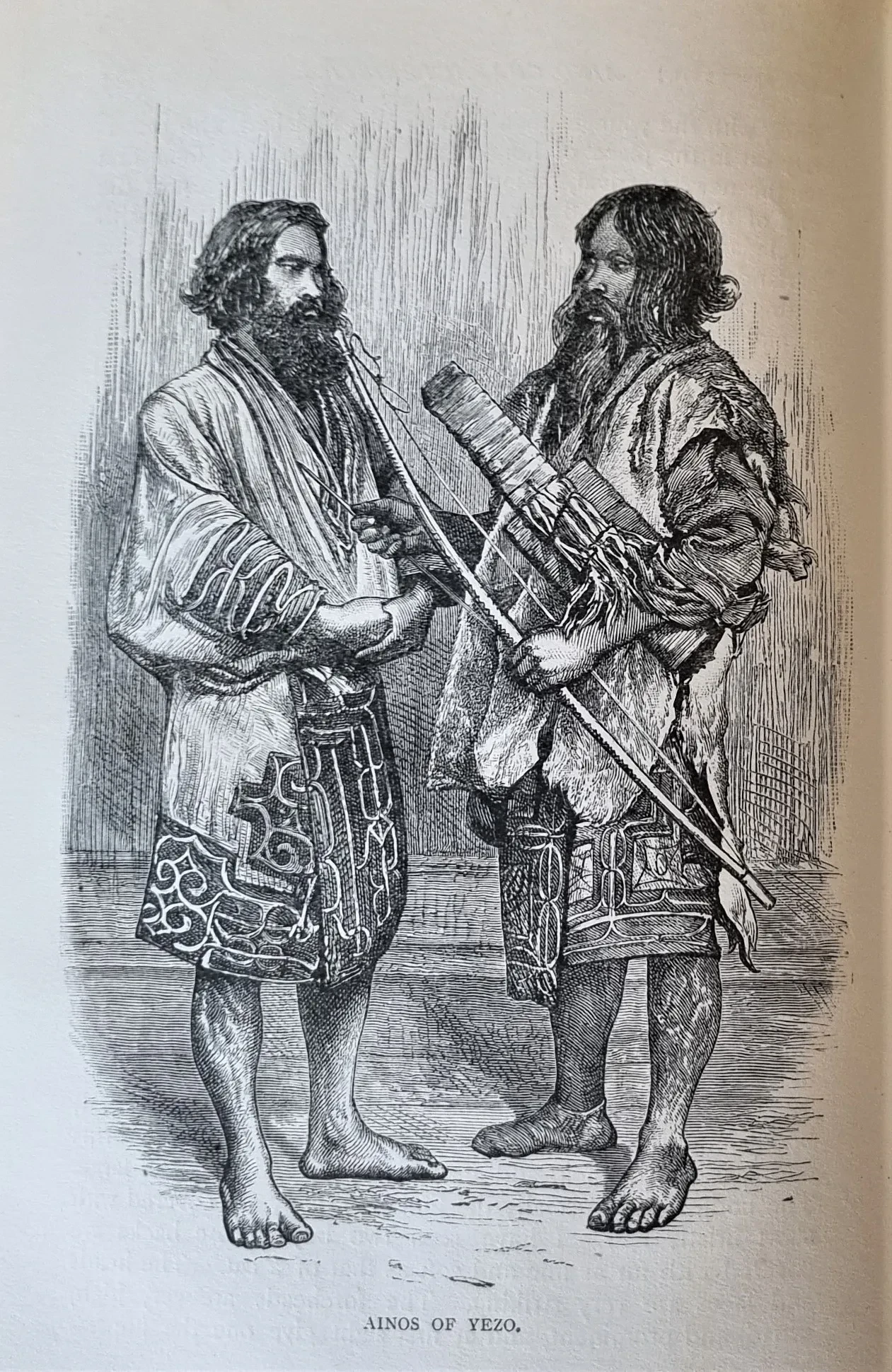

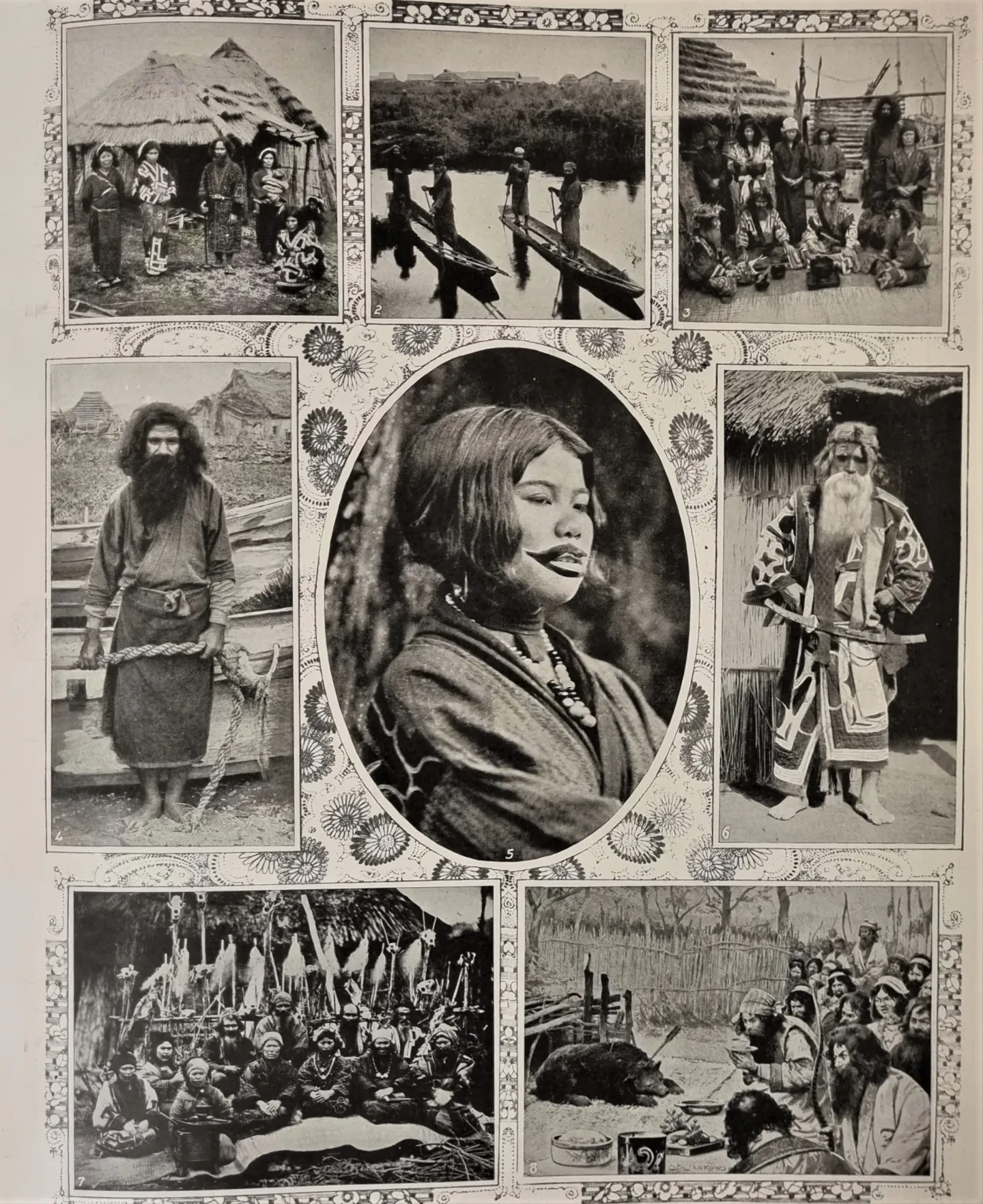

The Ainu (or 'Ino', as Holland spells it at the beginning of his journal before later settling on 'Aino') are indigenous peoples inhabiting primarily Hokkaido, but also the Kuril Islands, Sakhalin and other islands north of Japan, who, historically, relied on hunting and fishing.

For centuries, the Japanese population on mainland Japan had only sporadically come into contact with their remote Ainu neighbours and their languages, as well as cultural and social practices developed to a great extent separately from each other. Although, Japanese influence on Hokkaido gradually increased over the centuries.

In 1868, the newly established Meiji government officially annexed Hokkaido and its unregarded natives and for the next decades pushed through social and public regulations with the stated aim of assimilating the Ainu people into majority Japanese society and culture.

At the time of HMS Sylvia’s circumnavigation of Hokkaido, these assimilation policies were not yet in full swing but would soon threaten the Ainu’s way of life, language, and cultural identity.

Japanese discriminatory attitudes and disregard of the Ainu as beneath them did not go unnoticed by their British visitors in the late nineteenth century, as Holland notes that ‘[t]he Japanese treat them much like slaves & consider them as of an inferior creation to themselves’.

Holland also often remarks on the Ainu’s distinctiveness from the Japanese in their cultural practices, language as well as physical appearance. He writes of the Ainu:

The men are of an average height but strongly built & broad, they are very hairy & wear their hair rather long, beard & mustache untrimmed; the women are some of them really good-looking, they wear rings in the ears & have their mouths, round the lips, tattooed on in color, it does not extend far & is a sort of shading done in fine lines but in no particular direction, it extends all round the mouth; the older women have their arms also tattooed & the backs of the hands, in no particular pattern as far as I could see but in separate lines and patches.

He also describes the traditional Ainu houses:

[…] I went into one of the Aino huts & to my surprise I found it clean light and healthy looking. The embers in the square place in the centre where the fire is kept were nicely swept up, & there were numbers of little commodities & articles such as I did not expect to see, very rough it is true most of them were but neat & useful, in the fore place were a pair of wooden tongs, a small rake & a lamp with a neat stand, the suspender for the cooking pot was also ingenious […]. On either side of the hut was a large raised platform acting as bedsteads, they were raised about 2 feet off the ground & looked very clean […].

Traditionally, the Ainu’s spiritual beliefs are based on a form of animism, believing that nature as well as objects, creatures and places in it possess a spirit or god (or kamuy in the Ainu language).

When animals were hunted and killed for sustenance and furs, their spirits were ‘sent off’ from the mortal to the realm of the gods through rituals and prayers – bears being of particular importance as one of the main kamuy. Therefore, catching and raising bear cubs in the village to be sacrificed during the bear festival (Iyomante) had been a common practice around the time HMS Sylvia circumnavigated Hokkaido.

The crew also seemed excited about a potential bear hunt, but they would not get the chance to do so on this voyage. Coming across bear cubs in one of the Ainu villages he visited, Holland wrote:

For the first time we saw some bears here, there were altogether five kept in separate cages. These cages are constructed of stout oak branches lashed together so as to bring the lashing outside & thus prevent the bears from eating through it & the occupants were evidently well […]. The Ainos appear to have a sort of veneration for them as one of their greatest ceremonies is the fest of bears which is celebrated by the killing of one of these caged bears & a variety of forms are enacted on this occasion.

Circumnavigating the island and returning home

On 29 July 1871, after weeks of exploring the eastern coast of Hokkaido, HMS Sylvia coaled in the harbour of Hakodate and finally set off to circumnavigate the island. Proceeding north-eastwards, stopping in harbours and villages along the way, they eventually passed Hokkaido’s northernmost point at Cape Sōya, before catching a glimpse of the newly designated city of Sapporo and anchoring back at Hakodate harbour at 2:30am on 24 August – having taken nearly a month to complete their voyage.

After having finished their assignment at Hokkaido, HMS Sylvia and her crew returned to waters around the main island of Japan and in August 1872 were ordered back to England.

The Sylvia under command of Captain St John would eventually return to continue her surveying work of the Japanese coast in 1874, but without Swinton Colthurst Holland, who had moved on to HMS Bellerophon by then. Holland, after a long and successful career in the Royal Navy, would eventually be promoted to Admiral – just like his former captain on HMS Sylvia.

Search online for the documents relating to Swinton Colthurst Holland in the Caird Library and Archive’s catalogue (RMG reference: HND/100-104) and find out more about his career in the Royal Navy.

Captain St John also commemorated his experiences and time in Japan in his book Notes and sketches from the wild coasts of Nipon, which is also available in our collection (RMG reference: PBB0340).

Suggested readings

Bird, Isabella (1911): Unbeaten tracks in Japan: an account of travels in the interior including visits to the aborigines of Yezo and the shrine of Nikko. London: John Murray. (RMG reference: PBC6235)

Checkland, Olive (1989): Britain’s encounter with Meiji Japan, 1868-1912. London: The Macmillan Press.

Holland, Swinton Colthurst (1874): ‘On the Ainos’ In: The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 3, pp. 233-244. (Available on open access through JSTOR or on the computers in the Caird Library and Archive’s reading rooms)

Sjöberg, Katarina (1997): The return of the Ainu: cultural mobilisation and the practice of ethnicity in Japan. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

St John, Henry Craven (1873): ‘The Ainos: Aborigines of Yeso’, In: The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 2, pp. 248-254. (Available on open access through JSTOR or on the computers in the Caird Library and Archive’s reading rooms)

St John, Henry Craven (1880): Notes and sketches from the wild coasts of Nipon: with chapters on cruising after pirates in Chinese waters. (RMG reference: PBB0340)