In this bicentennial year of the modern railway, we take the opportunity to explore some railway connections in the Caird Library and Archive.

Researching railway history in a maritime museum might seem counterintuitive, yet, from the first transatlantic steamship to the Dunkirk evacuations, our maritime and railway heritage has long been interconnected.

Connecting cities

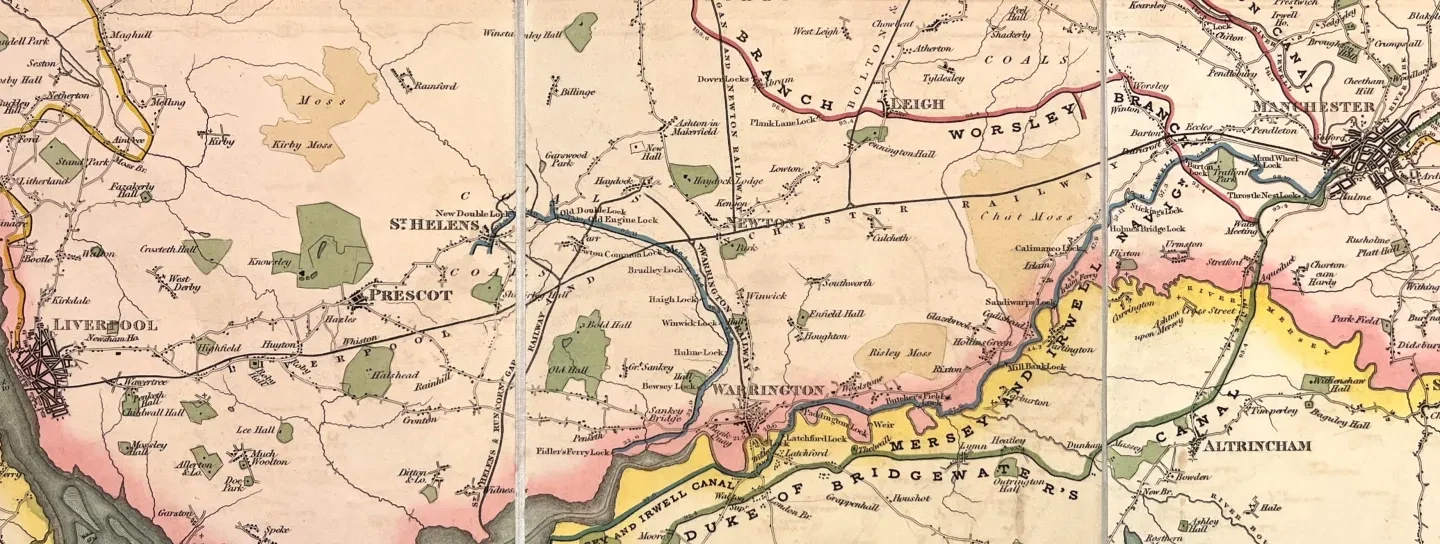

One of our earliest railway-related items is George Bradshaw’s Maps of Canals, Navigable Rivers, Railroads in the Principal Part of England (PBC4632). Over five maps of key infrastructure are shown across several southern, midland, and northern English counties through which the products of the Industrial Revolution flowed.

Part of a wider series known as the Maps of Inland Navigation, this set is largely concerned with canals and inland waterways and contains some of the earliest railway maps. Some of the railways depicted include the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (1830), which connected two cities by rail for the first time, and the proposed London and Birmingham Railway (1833). Those familiar with railway history may be amused to find Sir Nigel Gresley’s Canal, an eighteenth-century namesake and forebear of the renowned railway engineer.

Bradshaw is well known by railway historians and enthusiasts for his train timetables and travel guides. First appearing in 1839, Bradshaw’s Guides would continue in publication for well over a century, ending in 1961. The guides have enjoyed a revival in recent years through the BBC’s Great British Railway Journeys.

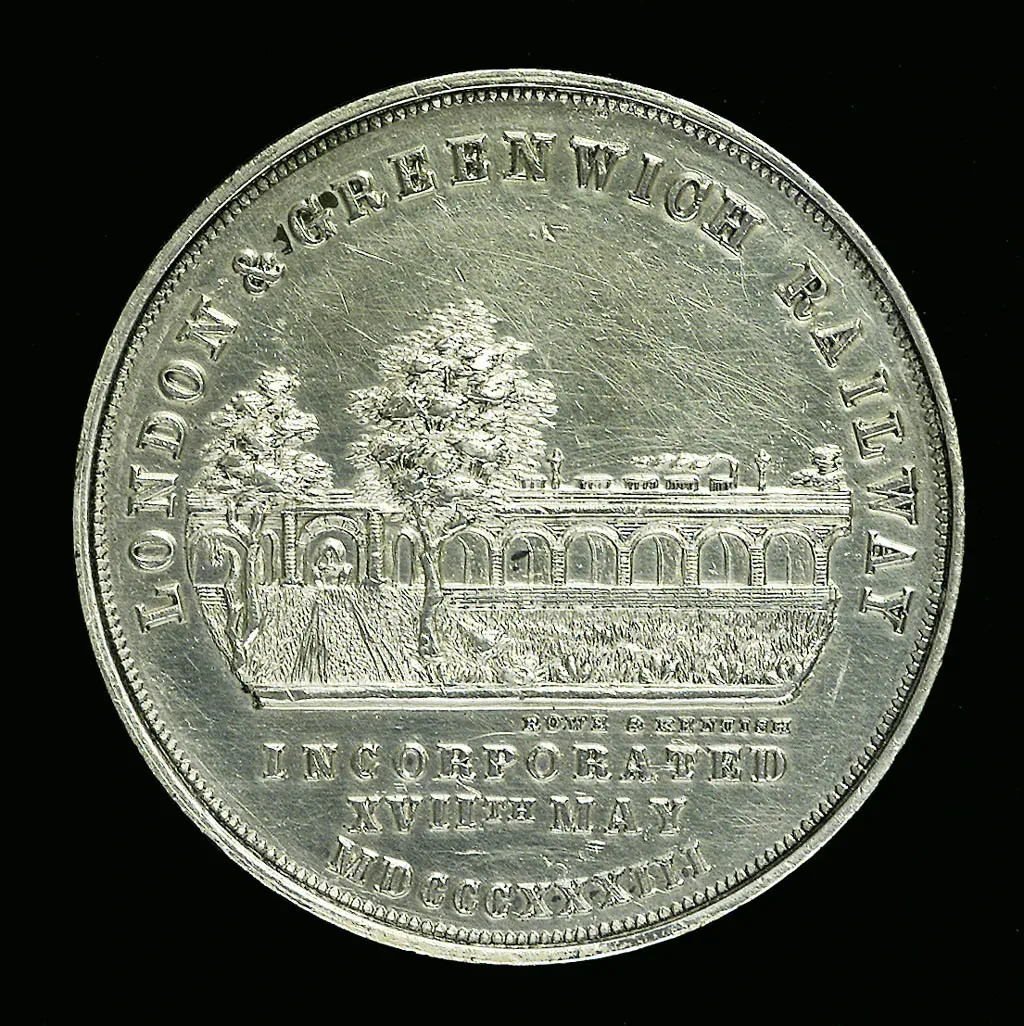

The railway came to Greenwich in 1837 when London’s first railway line, the London and Greenwich Railway, opened. On 14 December Gentleman’s Magazine reported that the celebrations were ‘attended by the Lord Mayor, Sheriffs, Aldermen, several Foreign Ministers, and many gentlemen connected with the scientific world.’ The highest praise, however, was reserved for those involved in conceiving and executing the works:

This great national work reflects the highest honour on the gallant projector Colonel Landmann, and no less credit to the contractor, Mr. Macintosh, under whose orders no less than sixty millions of bricks have been laid by human hands since the Royal Assent was given to the Act of Parliament for its formation in 1833.

Trains ran from London Bridge and initially terminated at a temporary station before the present Greenwich station opened in 1840. Proposals were put forward to extend the railway through Greenwich Park. A rare folio in our collection, Parliamentary Reports on the Proposal to Run a Railway through Greenwich Park (PBT1089), considers the risk to the work of the Royal Observatory with contributions from Royal Astronomer Sir George Biddell Airy.

To minimise disruption, it was agreed to dig a tunnel underneath the northern edge of the park now occupied by the National Maritime Museum. Completed in 1878, the tunnel connects Greenwich to a new station at Maze Hill, a short walk from the Museum.

In another fascinating maritime connection, two locomotives, reported by the London Illustrated News to be from the Greenwich Railway, were sold to the Admiralty in 1845. Their boilers were installed in Erebus and Terror– famously lost a few years later under Sir John Franklin while searching for the Northwest Passage.

Connecting continents

The rapid growth of transport infrastructure would continue, on land and at sea. The Great Western Railway (GWR), established in 1835, had set about joining London and Bristol by rail. Yet the company had an even more ambitious destination in mind, seeking to continue the route across the Atlantic Ocean to New York.

Although for legal and financial reasons these efforts were overseen by a separate company, this venture was unambiguously a railway initiative. Built by the Chief Engineer of GWR, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and named after the railway company that conceived it, in 1838 Great Western became the first steamship to cross the Atlantic. Amongst the treasures found within our Archive is LOG/M/50 – the captain’s logbook of Great Western on its maiden voyage from Bristol to New York and back in 1838.

Despite a promising start with great fanfare, ultimately the railways lost out to Cunard on the transatlantic passenger trade. Yet the desire to have a stake in sea traffic remained. Railways turned their attentions to ferries, often in co-operation with companies that ran services between Britain, Ireland, and the European continent.

The London and South Western Railway (LSWR) worked closely with the New South Western Navigation Company from the 1840s, both developing the sea link at Southampton in tandem. South Western conveyed passengers, goods, and mail to the Channel Islands and France. The LSWR eventually acquired ownership of the ferry fleet in 1862.

The business archive of the South Western Navigation Company, held at the Caird Library and Archive, offers some insight into the interconnectivity of rail and shipping. For example, SWS/9 contains agreements to transfer several steamers from New South Western to the LWSR, as well as some financial arrangements between the two companies, including payment for a £25,000 advance from LSWR in 1847.

Calamitous collisions

Rapidly expanding connectivity throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was not without risk. In 1870, while under LSWR ownership, an accident involving one of South Western’s ships occurred in the English Channel. En route to Jersey the paddle steamer Normandy collided with another ship in thick fog and sank. The disaster claimed nineteen casualties, including Normandy’s commander Henry Beckford Harvey.

The official inquiry into the loss of Normandy was held at Greenwich Police Court before the magistrate and nautical assessors. On 11 April the court delivered their judgement, reported in the 1870 Annual Register:

After carefully considering the evidence that has been adduced in this inquiry, the Court is of opinion that the Normandy, by a breach of the Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, is solely to blame for this disastrous collision.

The disaster had caught the attention of French author Victor Hugo, then living in exile in Guernsey. Writing to the editor of Guernsey’s The Star newspaper on 5 April 1870, Hugo held South Western ultimately responsible for the loss of life:

… in the face of these distressing catastrophes, it is important to remind rich companies, such as that of the South Western, that human life is precious, that seafarers deserve special concern, and that… if these three conditions of solidity for the ship, safety for the men, and lighting of the sea, had been met, probably no one would have perished in the sinking of the Normandy.

A few years later, in 1875, Hugo published his account of the incident in Deeds and Words – During Exile, defending the actions of Normandy’s captain:

So ends Captain Harvey. Let him receive here the farewell of the outlaw. No sailor in the Channel could equal him. After having imposed on himself all his life the duty to be a man, he exercised in dying the right to be a hero.

Connecting conflict

Railway shipping has played an invaluable role in major conflicts of the twentieth century. Many railway-owned vessels were built or requisitioned by the government for military service, moving troops and equipment across the English Channel. Some were involved in the Dunkirk evacuations during the Second World War.

During the First World War, three train ferries were built for the War Office by Armstrong Whitworth and Fairfield to help transport rail freight to the continent. These operated out of Richborough in Kent, where a port was constructed to supply the British Expeditionary Force. After the conflict the train ferries were employed on the Harwich–Zeebrugge route by the Great Eastern Railway and the Belgian Government.

All three train ferries were requisitioned by the Royal Navy for the Second World War, but only one survived the conflict. It was returned to the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) and scrapped in 1957 under British Railways. Train ferries continued operating on some cross-Channel routes until the opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1995 made them redundant.

Explore

Other connections between maritime and railway heritage to be found in the Caird Library and Archive include crew lists, Canadian Pacific Railway business archive, and the personal papers of railwayman Cuthbert Grasemann. Resources such as Lloyds List, Lloyds Register, and Mercantile Navy List are valuable for learning more about railway-owned vessels.

Beyond the Library and Archive, the Museum’s object collections contain a wide range of items linked to the railways. These include flags, caps and badges, posters, prints, plans, and photographs.

Search Collections Online to begin your journey today.

Further Reading

G.P. Orde. Dunkirk Withdrawal: Operation Dynamo May 26 to June 4, 1940: Alphabetical List of Vessels Taking Part, with their Services. PBP1209/1-4.

John Bold. Greenwich: an Architectural History of the Royal Hospital for Seamen and the Queen's House. Yale University Press, 2000. PBF0290.

Kevin Hoggett. Rails across the Sea: the Harwich - Zeebrugge Train Ferry Story. Mainline & Maritime, 2020. PBK0363.

Martyn Pring. Boat Trains: the English Channel and Ocean Liner Specials: History, Development and Operation. Pen & Sword Transport, 2020. PBK0015.

Michael Palin. Erebus: the Story of a Ship. Hutchinson, 2018. PBH8784.

Stephen Fox. Ocean Railway: Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Samuel Cunard and the Revolutionary World of the Great Atlantic Steamships. PBF5630.