Once adorning the walls of royal residences, the Solebay tapestry in Royal Museums Greenwich’s collection is prized for its exquisite detail.

Featuring burning ships, churning waves and columns of smoke, the tapestry depicts the events of the Battle of Solebay in May 1672, an inconclusive naval conflict between a Dutch fleet and a combined force of English and French ships.

Dating from the late 17th century, the work was originally part of a series of six giant tapestries commissioned by King Charles II to record the battle.

However, because of its age, size and high silk content, the tapestry is incredibly weak.

Thanks to the overwhelming response to our crowdfunding campaign, the tapestry has undergone extensive treatment at a specialist conservation studio in Brighton. It is now on display at the Queen's House in Greenwich.

From cleaning and lining to sewing and dyeing, textile conservator Zenzie Tinker gives an insight into the work involved in conserving this monumental masterpiece.

Why did the Solebay tapestry need conservation work?

Zenzie Tinker and her team carry out conservation treatments for a variety of textiles, from tapestries and curtains to ball gowns and vintage fashion.

The Solebay tapestry is one of the larger tapestries the team have worked on, measuring nearly four metres in height and around six metres in length.

An initial examination quickly revealed its fragile condition.

This is partly due to the weaknesses inherent in a tapestry’s structure. A tapestry is a woven structure that has threads running in both directions. It is made up of two types of threads: the warp and the weft.

The warp is the stronger thread and provides the structure of the tapestry. In historic tapestries like the Solebay tapestry, it would have been made from wool: a strong and flexible material.

Into the warp is woven the weft, the coloured threads that make up the design of the tapestry. Unlike the warp threads, the weft threads are discontinuous: they don’t run all the way through the tapestry. This allows the weavers to create changes in the design and colour.

However, this also creates vulnerabilities in the tapestry’s construction.

“On historic tapestries, the weight of the tapestry hangs on the discontinuous weft, which is the weakest part of the structure,” Tinker explains. “A lot of modern tapestry is woven so that it hangs on the warp, which makes it stronger and means it will last longer.”

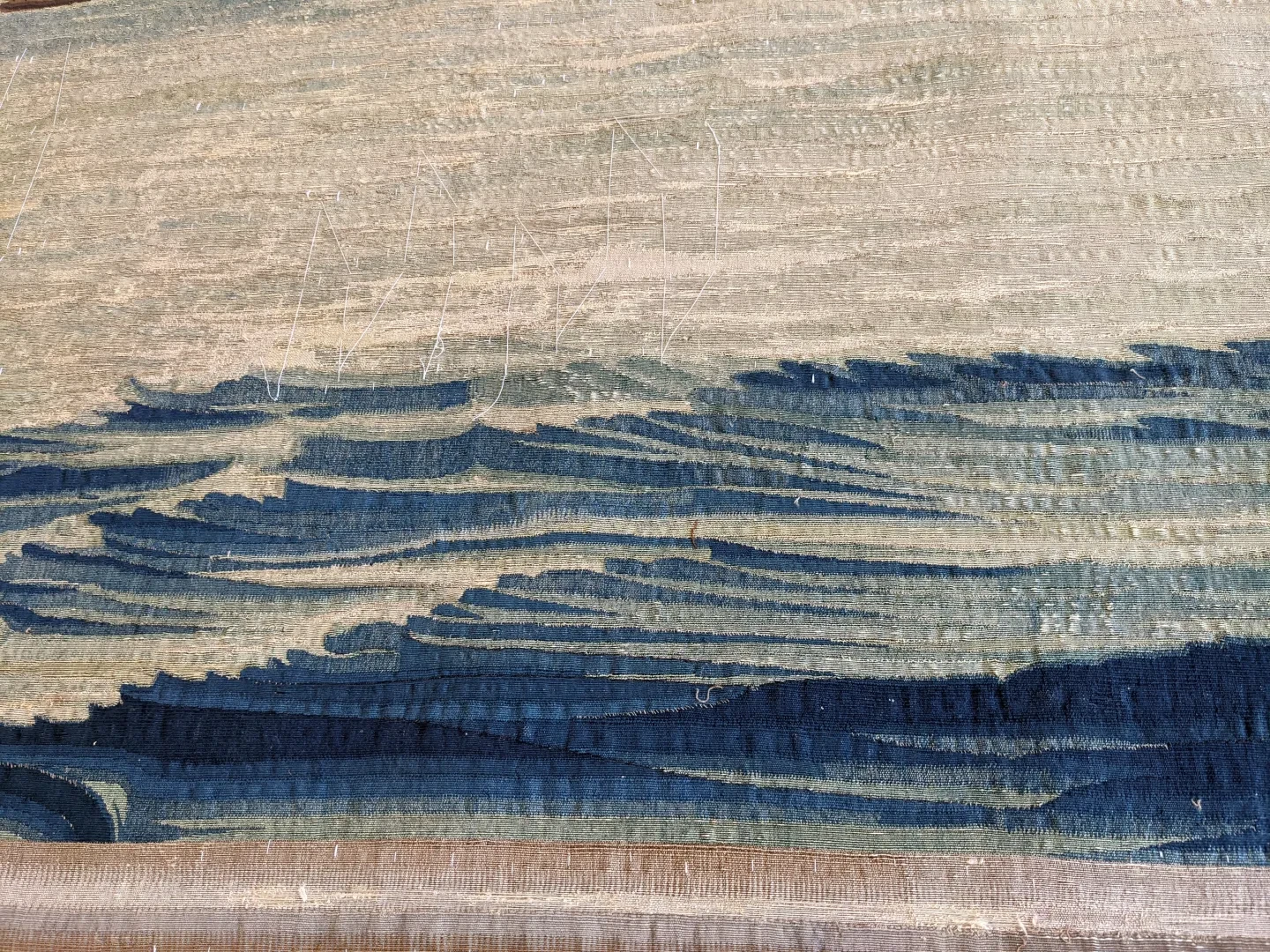

In the case of the Solebay tapestry, the weft is largely woven from silk, a fibre that degrades more quickly than wool – and is also more susceptible to light damage.

“The Solebay tapestry has a vast expanse of silk in the sea and sky, which makes the structure particularly weak and vulnerable,” Tinker says.

The tapestry’s age is also a contributing factor.

“The tapestry is more than 300 years old, and its condition had got to such a point that Royal Museums Greenwich couldn’t safely hang and display it without conservation,” Tinker says.

“Because of its size, the tapestry can’t really be displayed on a sloping board: it needs to be hung vertically for viewers to appreciate the perspective in the design.”

How was the tapestry conserved?

One of the first steps in the conservation journey involved preparing the tapestry for cleaning. As part of this 200-hour process, the team removed its tight linen lining and fabric patches, both of which had been added during previous repair work.

“The patches had degraded so much that they were powdering,” Tinker explains. “The threads that had been used in the repairs were in worse condition than the actual tapestry. This created a lot of dust, which would have impeded the cleaning if we left too much of it in place.”

The team also sewed support lines of tacking thread to strengthen the tapestry before it was sent for specialist wet cleaning in Belgium at the De Wit Royal Manufactory.

“The cleaning was very gentle: the tapestry was unrolled face down on a very large screen mesh within an enclosure,” Tinker says. “A slight vacuum was created, and water vapour and detergent vapour were passed through the tapestry. The tapestry was then rinsed thoroughly and dried.”

Strengthening the tapestry

Once the wet cleaning was complete, the team set to work reinforcing the tapestry’s weak structure. To do this, they created a full linen backing. This involved boiling and carefully preshrinking pieces of finely woven linen, pressing them dry and stitching the individual pieces together by hand.

The linen was attached to the tapestry using a special conservation frame consisting of three rollers arranged in a triangular formation.

First, the linen was rolled onto the middle roller, and its edge brought forward and attached to the front roller.

Then the tapestry was very carefully rolled onto the back roller, and its edge brought forward and attached over the top of the linen on the front roller. As work progressed, the tapestry was gradually rolled from the back to the front roller. It was stitched to the support linen in 20cm-wide sections until the work was completed.

The experience of tapestry weaving

With the support linen in place, the team started the stitching work – a painstaking process.

At least two conservators worked on the tapestry at any one time, coordinating their progress and completing each section before moving on to the next. There were 29 different sections in total, and the work took 18 months.

They plotted their progress on a large photograph of the tapestry taken before conservation. This helped to remind them of the “bigger picture”, as they did not see the full design of the tapestry again until the work was complete.

The conservators used a combination of threads to repair the tapestry, which were closely colour matched to the original threads as possible.

In areas of wool weft, the team custom dyed new wool threads.

“While the original threads in the Solebay tapestry were dyed with vegetable dyes – and possibly some dyes derived from insects – we use chemical dyes that have been tested to be light fast and wet fast, so we can predict how they are going to age and fade,” Tinker says.

To reinforce the silk weft areas, the conservators mixed a combination of stranded cotton and polyester thread.

“We use commercially available stranded cottons that have six strands per thread," Tinker says. "We draw out one cotton strand and combine it with one thread of polyester, often mixing two colours to match and blend in with the original silk. The mix of cotton and polyester also works well in terms of strength and lustre.”

The team used two different sizes of embroidery needles for the conservation work, as the sharp points allowed them to pull through threads without damaging any original fibre. The conservators would sit at the tapestry frame passing the needle up and down through the tapestry and the linen, from the upper to lower hand each time.

“Even though the team are experienced tapestry conservators, it takes a while for them to get their eye in and to work together, as every tapestry is slightly different from the last one,” Tinker says. “It’s lovely work and does have a rhythm to it. One has to make decisions the whole time about colours and where one's placing the needle.”

An eye for detail

Another part of the conservation process involved reviving important visual elements in the tapestry’s design. The dark coloured rigging of the ships' sails for example were carefully reinstated, as were the ships' national flags.

For Tinker and the conservators, seeing the tapestry’s details up close was particularly exciting.

“We’ve all appreciated the beauty of the weaving in the sea and sky,” Tinker says. “At first glance, one might think it is just a wide expanse of light-coloured silk, but when one actually looks at the skill of the weaving and the way the weavers have manipulated the thread to give these waves crests and create foam, it’s really beautiful.”

Another of Tinker’s favourite parts of the tapestry is the elaborate borders: “The borders are such fun, and have these wonderful double-tailed mermen, and lots of fish and motifs connected to the sea.”

The Solebay story

Sign up to the art newsletter for more information about the Solebay tapestry, and find out more about exhibitions and events at the Queen's House.

The finishing touches

Once the stitching was complete, the team rolled back through the tapestry, checking the consistency of their work.

“Sometimes we deliberately leave something until the end because we need to consult with the curator, or we want to look at it again later with fresh eyes,” Tinker explains.

The tapestry was then taken off the frame and laid face down. The team trimmed the linen support, leaving a bit of a border, then folded and sewed it back to itself on the reverse of the tapestry.

With this in place, the team then made a down proof cotton lining – a process that took around 150 hours to complete. “It’s a bit like lining a huge curtain,” Tinker says. “We connect the lining to the tapestry via many vertical lines of locking stitch as well as around each edge. If one left it hanging free, it would cause a big billowing sail.”

Finally, a strip of contact fastener was hand stitched to the top of the tapestry, which allowed the work to be displayed once more. “The tapestry can then hang freely from just one piece of VELCRO®,” Tinker says.

Before it was returned to Royal Museums Greenwich, the tapestry was hung two or three times. This allowed it to drop and relax after being rolled up tightly and under tension on the tapestry frame for so long.

For Tinker and the team, hanging the tapestry for the first time after completing the conservation is an emotional experience: “The conservators and I quite often get teary when we see the finished tapestry hanging, because months of our working life have gone into conserving it.”

Ready for display

Thanks to your generous support, the conservation of the Solebay tapestry was completed in February 2023. It is now on display at the Queen's House in Greenwich.

The Solebay tapestry is based on drawings by Willem van de Velde the Elder, who had a studio at the Queen’s House and worked on the designs for the tapestry in the actual building.

Tinker hopes the tapestry will encourage visitors to find out more about tapestry weaving.

“We feel a real connection with the weavers because we’re working so closely and intimately with the tapestry, poring over every detail,” Tinker says. “We’re thrilled to be involved in the project, and we feel very privileged to be doing the work.”