From wealthy officers to working-class sailors, the representation of naval personnel has been a significant branch of British art for over five hundred years. Royal Museums Greenwich holds the largest collection of British naval portraits in the world, including paintings, drawings, prints and sculpture from the sixteenth century to the present day.

Historically, these portraits were associated with power. They represented only those who occupied senior positions in the Royal Navy, most of whom were white, wealthy and male. When looking at naval portraiture today, it is important to consider the prejudices and biases that once shaped the genre. Who got to have their portrait painted, and who did not? Whose interests were served by these artworks, and whose were not?

Portraits show us how the Royal Navy was viewed at different moments in history. They also reveal the concerns and aspirations of individuals and families caught up in naval affairs. Many are innovative and important works of art. For centuries, naval portraits have forged, reinforced and challenged ideas of gender, heroism and loyalty. They have functioned as icons of empire, records of service and personal mementos.

Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art (Post-1800), shares insights from her new book, The Art of Naval Portraiture, which unpacks the complex history of this important genre.

1. The early history of the Royal Navy

Although the Royal Navy was formally founded by Henry VIII in 1546, naval officers initially lacked a coherent identity. Some were noble courtiers, while others were professional sailors. Many combined naval careers with other activities, such as scholarship, politics and commerce.

Portraits reflect the varied careers of naval officers from this time. Captains and admirals were occasionally painted with symbols of seafaring, such as globes, but many preferred to be depicted with emblems of their lives ashore.

Admiral Sir John Hawkins (probably) by The Master of the Countess of Warwick

About 1565, oil on panel (BHC4185)

It is not clear who this portrait depicts. It was once believed to represent Admiral Sir Richard Hawkins, but recent research has revealed that the painting is earlier in date than previously thought. This has led to the suggestion that it may actually represent Richard’s father, Sir John Hawkins, who was a naval officer and slave trader.

The face does share similarities with other portraits of John Hawkins, but this new identification is still speculative. It is not even certain that the man depicted is a naval officer. His clothing is not specifically maritime: he is dressed in ornate armour of the kind used in court jousts, tournaments and entertainments. Meanwhile, the background of the portrait features a representation of a Latin proverb. However, X-rays reveal that this motif is a later addition, painted over the picture’s original background, which was a field of striped tents.

These tents were presumably intended as a reference to a tournament or military campaign. This portrait highlights the difficulty of identifying naval portraits at a time when seafarers were often depicted in the same way as landbound courtiers.

2. The development of naval portraiture

After Charles II took the throne in 1660, the Royal Navy underwent a process of reform and professionalisation. Naval administrator (and famous diarist) Samuel Pepys oversaw the creation of an official framework for the training, payment and promotion of officers.

This gave rise to a sense of shared professional identity, which was reflected in portraiture. Artists developed a specific formula for depicting naval personnel. Officers were shown in coastal settings with battles from their careers in the background. Anchors, telescopes, cannons and other pieces of nautical paraphernalia were often included.

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle by Peter Lely

1665–66, oil on canvas (BHC2508)

In this portrait, Monck rests one arm on an anchor. He is dressed in a buff coat, a padded leather garment which was used as a flexible and lightweight alternative to metal armour. Gold stripes have been worked into the coat’s sleeves, highlighting Monck’s wealth.

The portrait comes from the ‘Flagmen of Lowestoft’, a series of 13 paintings commissioned by the Duke of York (later King James II) to commemorate the victory of the English fleet over the Dutch at the Battle of Lowestoft on 13 June 1665. Each portrait in the series depicted a senior commander, or ‘flagman’, who fought in the battle. The officers were all shown on the seashore with attributes of naval command, including cannons, globes, swords and anchors.

Lely was not the first artist to depict naval officers in this way. However, as high-profile artworks in the royal collection, the ‘Flagmen of Lowestoft’ influenced other painters to adopt this formula for naval portraiture.

3. The introduction of naval uniforms

The first official naval uniform was introduced in April 1748. It was only for officers, being intended to reinforce their authority at sea and their social status ashore. Common sailors would not receive a uniform of their own for another 100 years.

The public learnt to recognise officers’ uniforms through portraits. Thanks to a booming print market and the advent of public art exhibitions in the mid-1700s, an increasingly large audience was exposed to naval portraiture. The names of successful officers were frequently mentioned in the press, stimulating demand for their images.

Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Saunders by Joshua Reynolds

About 1760, oil on canvas (BHC3012)

In this portrait, Saunders wears the uniform of a vice-admiral and rests his right hand on the crown on an anchor. This painting was reproduced as a high-quality mezzotint (a type of tonal engraving), and it was also printed as an illustration in a number of popular magazines.

A copy of the portrait even went on display in May 1762 at Vauxhall Gardens, London. The Gardens were a popular public attraction, where large crowds flocked to see artworks, musical entertainments and performances and, in some cases, to engage in playful flirtation and sexual encounters.

In keeping with this romantic ambiance, Saunders’s portrait was depicted in the arms of a naked female sea nymph as part of a large mural celebrating British naval supremacy. This example demonstrates how naval portraits at one time suffused British popular culture, sometimes turning up in the most unexpected places.

Find out more about the Vauxhall Gardens mural

4. A new era for the Royal Navy

After defeating Napoleonic France in 1815, Britain was left without any major international rivals. In the century that followed, the Royal Navy was instrumental in maintaining this global dominance, but its role and technology underwent a rapid evolution.

Sailing ships were replaced with steam-powered vessels, which were primarily employed in surveying, peacekeeping and policing rather than conflict. This shift had consequences for naval portraiture. Artists had to develop new imagery to reflect emerging areas of naval activity, such as polar exploration. Fewer and fewer portraits adhered to the age-old formula of showing a naval officer on the seashore.

Rear-Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort by Stephen Pearce

1855–56, oil on canvas (BHC2541)

Beaufort served as Hydrographer to the Navy between 1829 and 1855. In this role, he oversaw the commissioning and publishing of marine charts and coastal surveys. His career epitomised the bureaucratic values of the early Victorian era, when Britain endeavoured to impose order upon its vast empire via official records, science, statistics and new technologies.

The portrait alludes to Beaufort’s role as a hydrographer and administrator. The setting appears to be an office or gentleman’s study. Beaufort is dressed in civilian clothes with a pair of spectacles in his hand and a double-lensed magnifying glass on a cord around his neck. These optical aids testify to his involvement in the detailed scrutiny of charts and documents.

The portrait was painted for the National Gallery of Naval Art in the Painted Hall at Greenwich. Established in 1824, this gallery promoted the Royal Navy through displays of portraits, battle paintings, sculptures, ship models and assorted nautical ephemera.

5. State-sponsored war art

The First World War (1914–18) heralded a fundamental shift in the relationship between art and war. For the first time in British history, the government sponsored artists to represent the conflict, establishing a tradition of official war art.

Previously, most war art had come about through private commissions from wealthy commanders, who could afford to pay for expensive artworks. The impact of government patronage on naval portraiture was significant, since it led to more working-class service personnel being depicted. Portraits of the lower ranks commemorated the valuable contributions that ordinary people were making to the war effort, but they were also used for propaganda purposes.

John Travers Cornwell, Boy First Class by Ambrose McEvoy

About 1918, oil on canvas (BHC2635)

This portrait was commissioned by the government. It was intended to commemorate the death of a 16-year-old sailor called John Travers Cornwell, who died in June 1916 from fatal injuries sustained at the Battle of Jutland.

McEvoy based the portrait on a photograph but struggled to create a convincing likeness. He therefore abandoned the portrait in an unfinished state, having only completed the brown-toned underpainting. It was later suggested that he had accidentally used a photograph of Cornwell’s younger brother, George, rather than one depicting Cornwell himself.

The portrait could be written off as a failure: a ham-fisted attempt to mark the tragic loss of a working-class boy from east London. However, the painting remains incredibly powerful, in spite – or perhaps because of – its shortcomings. The faded colours evoke the idea of a young life ended too soon. Meanwhile, the fact that it may depict the wrong member of the Cornwell family creates a poignant, if unintended, reminder of how enlisted men were often treated as a disposable resource.

6. New perspectives on naval portraiture

For five centuries, naval portraiture has been a complex and creative branch within British art. Today, it remains important and relevant.

Naval portraits are records of events, individuals and stories that have shaped the world around us. Here at Royal Museums Greenwich, we are constantly undertaking new research and growing our collection in order to develop our understanding of this important genre.

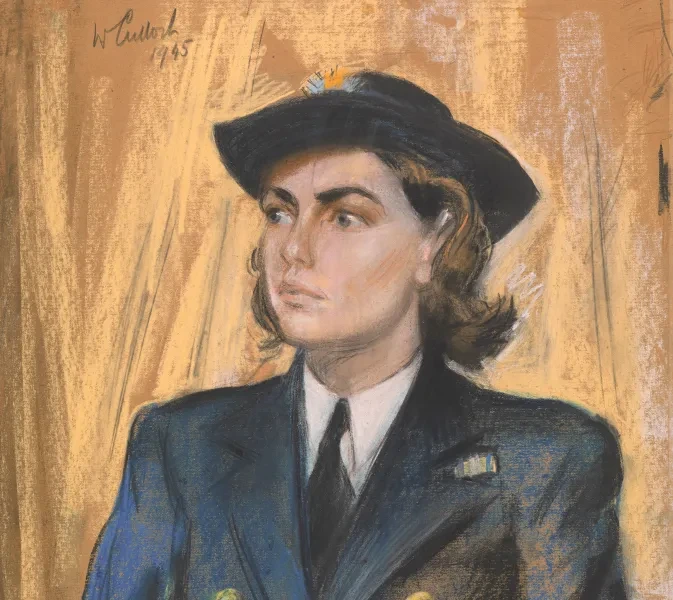

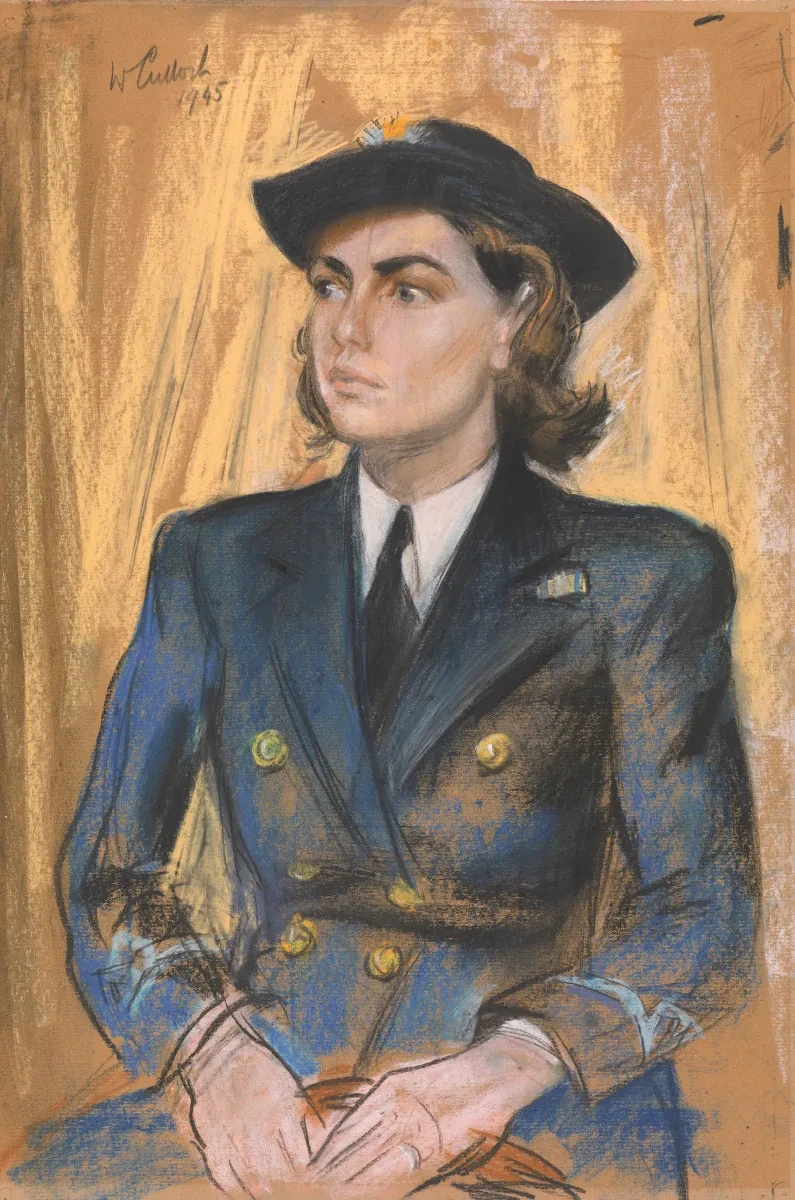

Wren Officer (Third Class) by Joseph McCulloch

1945, pastel on paper (ZBA9617)

This portrait depicts a Third Officer in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, also known as the Wrens. Acquired in late 2022, it was the first portrait of a woman in a naval role to enter the Museum’s collection. Increasing the representation of women in the collection will take time, but this acquisition is an important step towards that goal.

The continued growth of the collection helps us to tell a broader variety of stories about naval service. The name of the woman represented in this portrait is not currently known, but it is hoped that further research will reveal her identity. The portrait was made by Joseph McCulloch in Chelsea in 1945.

Main image: England's Pride and Glory by Thomas Davidson (BHC1811)