Alongside the work of famous campaigners and formerly enslaved people living in London, one of the key events in the abolition movement was a rebellion on the island of Haiti.

Learn more about the campaigns to end slavery in Britain, and how the legacies of enslavement still shape the world around us today.

Every year on 23 August, the National Maritime Museum commemorates International Slavery Remembrance Day, featuring a day of talks, workshops and performances exploring the transatlantic slave trade and its legacies.

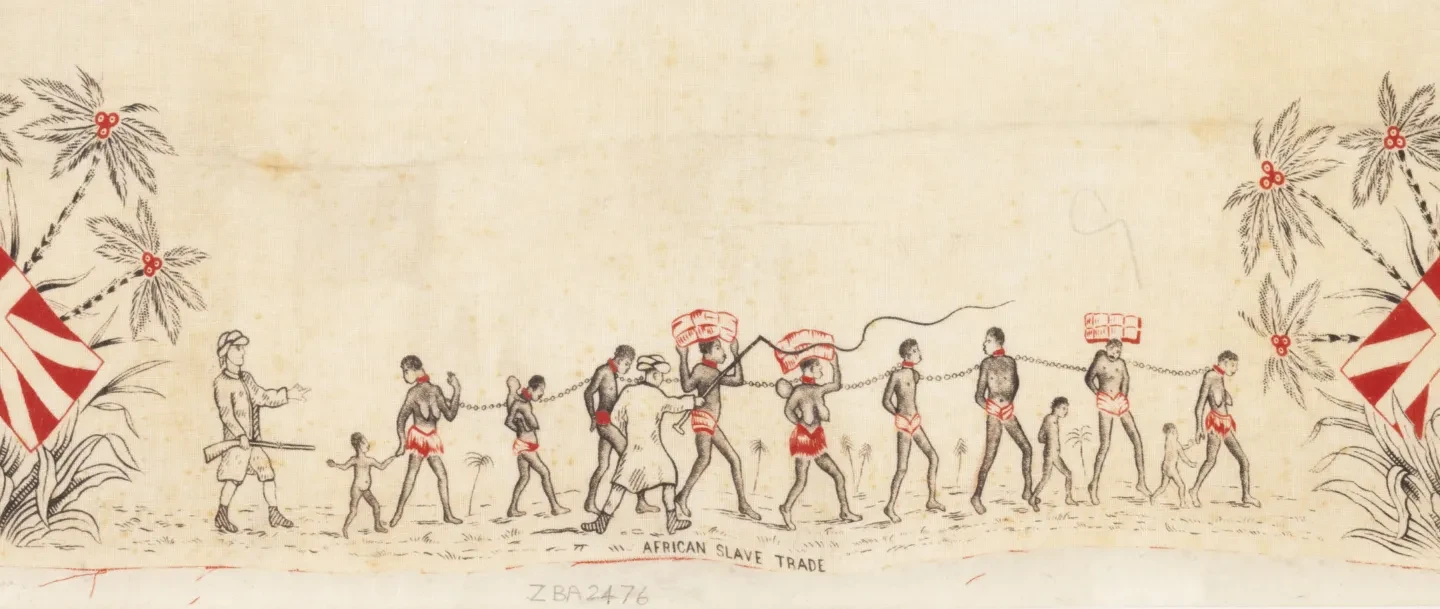

Key facts about the transatlantic slave trade

- Between 1662 and 1807 British and British colonial ships purchased an estimated 3,415,500 Africans. Of this number, 2,964,800 survived the 'middle passage' and were sold into slavery in the Americas.

- The transatlantic slave trade was the largest forced migration in human history and completely changed Africa, the Americas and Europe.

- Only Portugal/Brazil transported more Africans across the Atlantic than Britain.

- Until the 1730s, London dominated the British trade in enslaved people. It continued to send ships to West Africa until the end of the trade in 1807.

- Because of the sheer size of London and the scale of the port’s activities, it is often forgotten that the capital was a major slaving centre.

- Between 1699 and 1807, British and British colonial ports mounted 12,103 slaving voyages - with 3,351 setting out from London.

How did the slave trade abolition campaign begin?

As the trade in enslaved people reached its peak in the 1780s, more and more people began to voice concerns about the moral implications of slavery and the brutality of the system.

From the beginning, the inhuman trade had caused controversy. London was the focus for the abolition campaign, being home both to Parliament and to the important financial institutions of the City.

As early as 1776, the House of Commons debated a motion 'that the slave trade is contrary to the laws of God and the rights of men'.

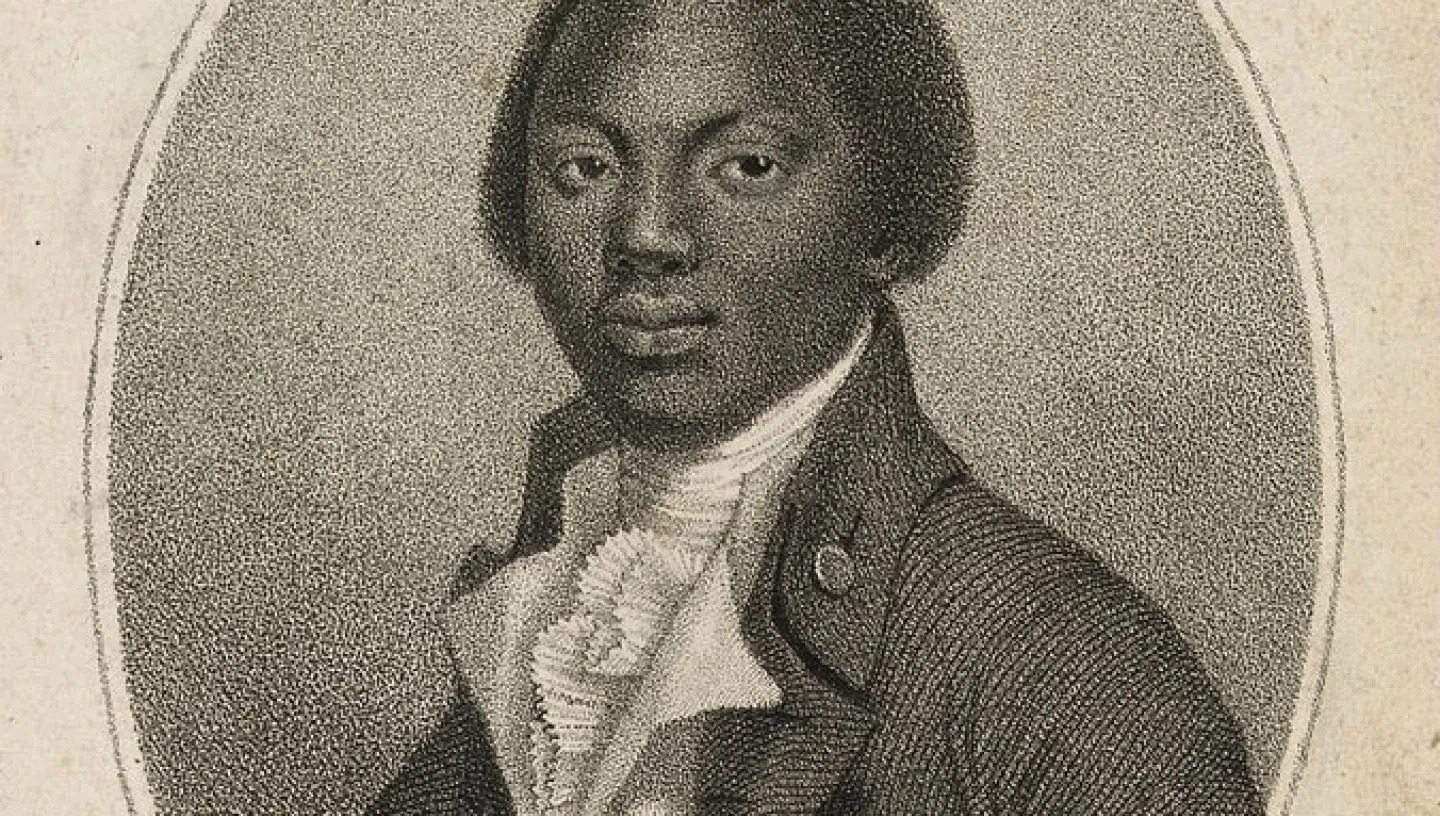

Key campaigner: Ignatius Sancho

Ignatius Sancho was born in 1729 on a slave ship bound for the Caribbean.

Orphaned at the age of two, he was taken to Britain where he was given to three sisters in Greenwich. A chance meeting with the Duke of Montagu (1690-1749) changed the young Sancho’s life. Montagu was taken by the child’s intelligence, and encouraged his education. After Montagu’s death in 1749, Sancho persuaded his widow to take him away from his mistresses, and she hired him as a butler.

With the support of the Montagu family, Sancho established a grocery in Westminster (ironically selling slave-produced commodities). His wealth and property secured him the vote.

Sancho moved in, and corresponded with, a wide and influential social circle of nobles, actors, writers, artists and politicians. He was a supporter and patron of the arts, as well as being a composer in his own right. Sancho died in December 1780, and was the first African in Britain to receive an obituary.

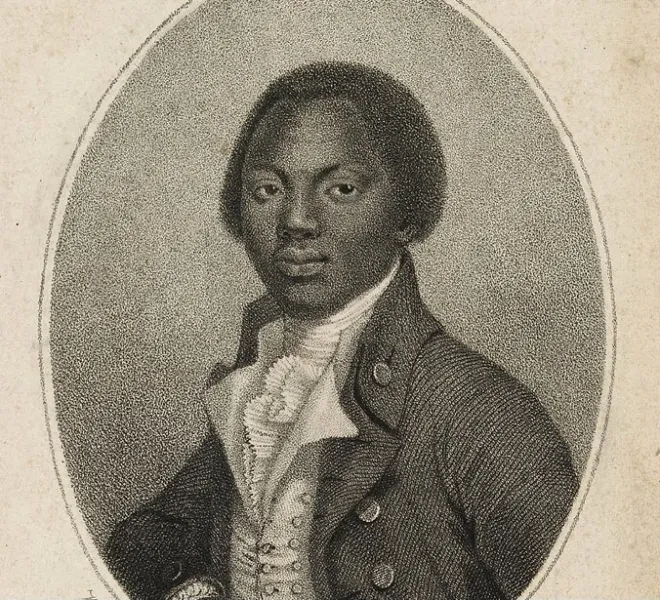

Key campaigner: Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano was also a hugely significant figure in the abolition campaign.

According to his autobiography, Equiano was captured in West Africa, forcibly transported to the Americas and sold into slavery. He eventually managed to buy his freedom. Equiano published his autobiography – The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings – in 1789. It was reprinted many times, becoming one of the most powerful condemnations of the trade and an enormously important piece of abolitionist literature.

The video above features historian S.I. Martin and is taken from Ships, Sea and the Stars, an online discussion series hosted by Helen Czerski.

Why did it take so long for Britain to ban slavery?

The task faced by the abolitionists was enormous. Parliament passed legislation restricting the number of Africans that could be carried on an individual ship, but the scale of the trade continued to grow throughout the abolition campaign.

Between 1791 and 1800, around 1,340 slaving voyages were mounted from British ports, carrying nearly 400,000 Africans to the Americas. In 1798 alone, almost 150 ships left Liverpool for West Africa.

New colonies in the Caribbean and the continued consumer demand for plantation's goods fuelled the trade.

Learn more about the slave trade records in the National Maritime Museum's collections.

Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, and the end of the slave trade in Britain

Clarkson and Wilberforce were two of the most prominent abolitionists, playing a vital role in the ultimate success of the campaign.

Clarkson was a tireless campaigner and lobbyist. He made an in-depth study of the horrors of the trade and published his findings. Clarkson toured Britain and Europe to spread the abolitionist word and inspire action. As a result, the abolition campaign grew into a popular mass movement.

William Wilberforce was the key figure supporting the cause within Parliament. In 1806-07, with the abolition campaign gaining further momentum, he had a breakthrough.

Legislation was finally passed in both the Commons and the Lords which brought an end to Britain’s involvement in the trade. The bill received royal assent in March and the trade was made illegal from 1 May 1807. It was now against the law for any British ship or British subject to trade in enslaved people.

Although the abolitionists had won the end of Britain’s involvement in the trade, plantation slavery still existed in British colonies. The abolition of slavery now became the main focus of the campaign though this was a long and difficult struggle. Full emancipation was not achieved until 1838 and none of the ex-slaves received compensation.

The Haitian revolution and the slave trade

The campaign to end slavery coincided with the uprisings of the French Revolution and the retaliation of enslaved communities in the British colonies.

Revolution in Saint Domingue

On 23 August 1791 a massive revolt by enslaved Africans erupted on the island of Saint Domingue, now known as Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The uprising would play a crucial role in making Saint Domingue the first Caribbean island to declare its independence and only the second independent nation in the Western Hemisphere.

The island had become one of the wealthiest producing colonies and therefore attracted the interest of the French, the Spanish and the English, three of the world’s strongest powers at the time. There were a number of factors that led to the rebellion, one of which was the French Revolution in 1789, which called for ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ (liberty, equality and fraternity).

Toussaint L’Ouverture

For 13 years, the country was in a state of civil war with the enslaved fighting for their freedom under the leadership of their fellow Africans.

One of the most successful commanders was Toussaint L’Ouverture, formerly enslaved domestically. Under the military leadership of Toussaint, the freedom fighters were able to gain the upper hand and defeat the French, Spanish and British forces that attempted to regain control.

Toussaint died in 1803 but the wheels of change were in motion. The rebel forces continued to fight for their freedom and on 1 January 1804 Haiti was declared an independent republic.

The Haitian Revolution, as it became known, was the only successful slave rebellion in world history. It became a pinnacle of resistance for enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and the Americas and was a turning point in the fight to abolish transatlantic slavery.

Three years later, on 25 March 1807, King George III signed into law the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, banning trading in enslaved people in the British Empire.

Today, 23 August is known as the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. This marks the proclamation of the first black state, Haiti – symbol of the struggle – and the triumph of the principles of liberty, equality, dignity and the rights of the individual.