The aurora is one of the most spectacular displays in the night sky – but how are these curtains of colourful light formed?

Learn more about what causes the aurora borealis with astronomers from Royal Observatory Greenwich, and discover the secrets of photographing the 'Northern Lights' with award-winning entrants from Astronomy Photographer of the Year.

What is the aurora?

The aurora can be seen near the poles of both the northern and southern hemisphere. In the north the display is known as the aurora borealis; in the south it is called the aurora australis.

These 'northern' and 'southern lights' have fascinated, frightened and inspired humans for centuries. More recently, photographers have gone to remarkable lengths to try and capture the beauty of these atmospheric events.

What causes the aurora borealis or 'northern lights'?

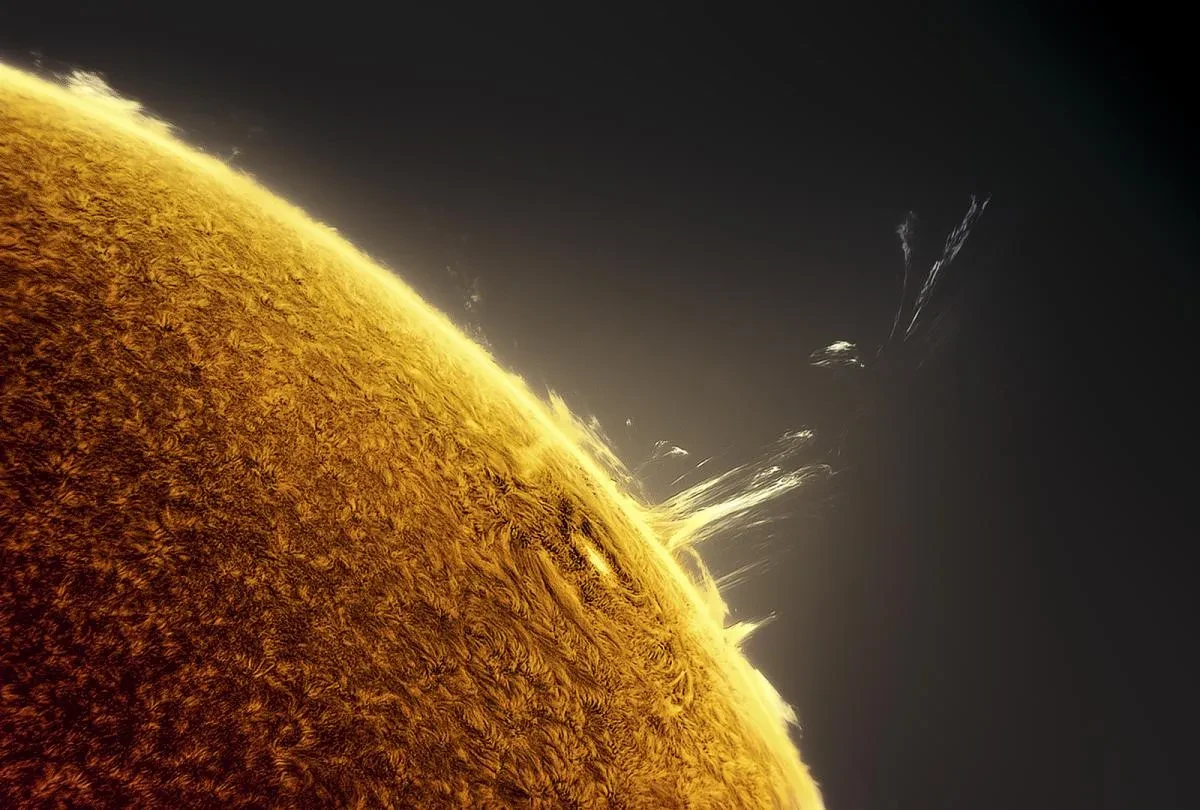

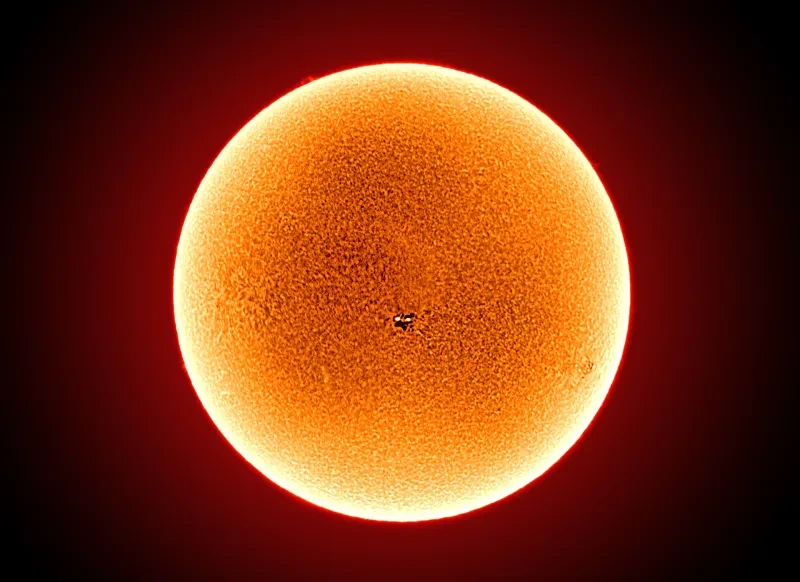

The lights we see in the night sky are caused by activity on the surface of the Sun.

Solar storms on our star's surface give out huge clouds of electrically charged particles. These particles can travel millions of miles, and some may eventually collide with the Earth.

Most of these particles are deflected away, but some become captured in the Earth’s magnetic field, accelerating down towards the north and south poles into the atmosphere. This is why aurora activity is concentrated at the magnetic poles.

“These particles then slam into atoms and molecules in the Earth’s atmosphere and essentially heat them up,” explains Royal Observatory astronomer Tom Kerss. “We call this physical process ‘excitation’, but it’s very much like heating a gas and making it glow.”

We are therefore seeing atoms and molecules in our atmosphere colliding with particles from the Sun. The aurora's characteristic wavy patterns and 'curtains' of light are caused by the lines of force in the Earth’s magnetic field.

The lowest part of an aurora is typically around 80 miles above the Earth's surface. However, the top of a display may extend several thousand miles above the Earth.

What are the different colours in the aurora?

Different gases give off different colours when they are heated. The same process is also taking place in the aurora.

The two primary gases in the Earth’s atmosphere are nitrogen and oxygen, and these elements give off different colours during an aurora display.

The green we see in the aurora is characteristic of oxygen, while hints of purple, blue or pink are caused by nitrogen.

“We sometimes see a wonderful scarlet red colour, and this is caused by very high altitude oxygen interacting with solar particles,” adds astronomer Tom. “This only occurs when the aurora is particularly energetic.”

Is the aurora borealis visible in the UK?

The aurora borealis can be seen in the northern hemisphere, while the aurora australis is found in the southern hemisphere.

While the best places to see the aurora are concentrated around the polar regions, the aurora borealis can sometimes be seen in the UK. The further north you are, the more likely you are to see the display – but heightened solar activity has meant that the northern lights have very occasionally been seen as far south as Cornwall and Brighton.

The conditions do still need to be right, however. Dark and clear nights, preferably with little light pollution, offer the best chance of seeing the aurora.

Lancaster University's Department of Physics runs a website called AuroraWatch UK, which estimates the likelihood of an aurora being visible based on geomagnetic activity.

Never miss a shooting star

Sign up to our space newsletter for exclusive astronomy news, guides and events, and stay connected with Royal Museums Greenwich.

Image in focus

Aurora Borealis Over Brighton Seafront by Michael Steven Harris

Taken in Brighton, East Sussex, UK, 1 November 2023

"High auroral activity provided the opportunity to try and capture Aurora Borealis by drone from Brighton seafront," photographer Michael explains.

"While I wasn’t sure if it was possible due to Brighton’s significant light pollution and the drone’s tiny sensor, I immediately knew I’d succeeded once I saw the distinctive colours in the sky on the back of my drone controller screen."

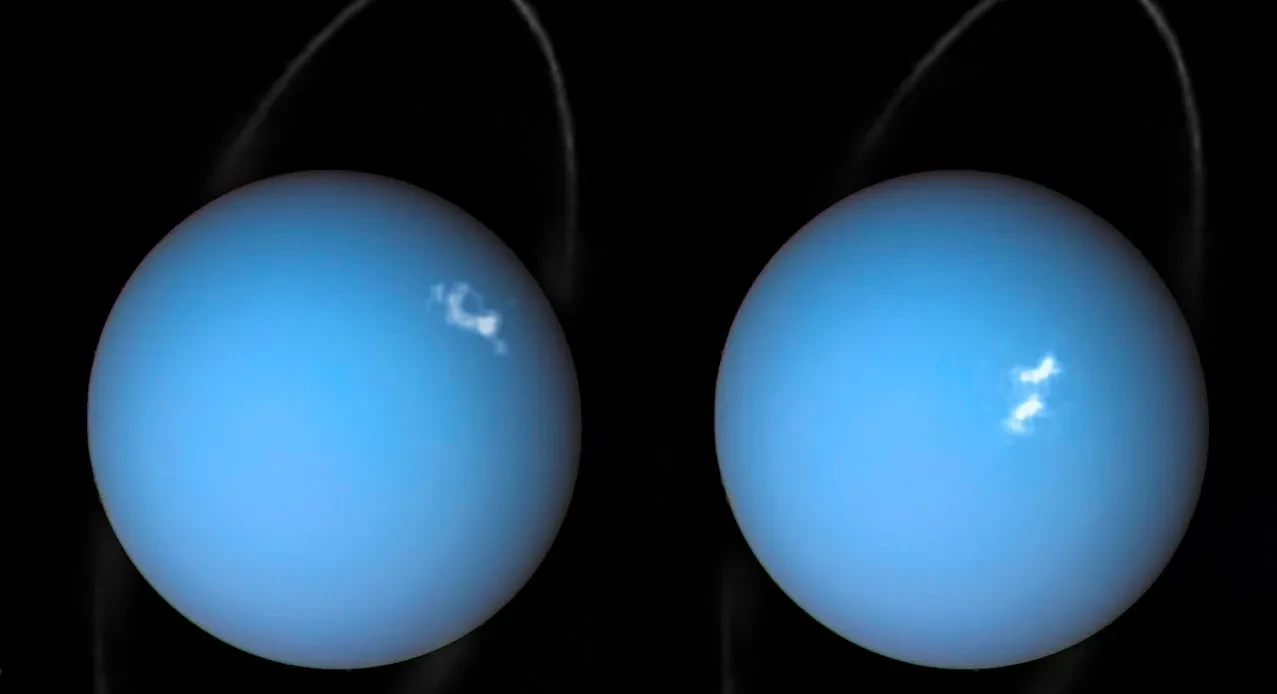

Do other planets have aurorae?

Any planet with an atmosphere and magnetic field is likely to have aurorae. Scientists have captured incredible images of aurorae on Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

Aurorae on Mars have also been seen, but as the 'red planet' does not have a global magnetic field, aurorae behave differently and appear to be far more widespread.

What are solar flares and how do they affect the aurora?

The aurora is a very dramatic example of the ways in which solar activity affects the Earth.

Solar flares are like enormous explosions on the surface of the Sun in which streams of charged particles are emitted into space. It typically takes two days after the flare is seen on the Sun for the particles to reach Earth. Upon their arrival, these particles can result in aurora activity.

What are geomagnetic storms?

Intense aurora displays are generated following massive explosions on the Sun known as 'coronal mass ejections'. These explosions release clouds of hot plasma containing billions of tons of material travelling at around two million miles per hour. When the clouds reach the Earth, they interact with the Earth's magnetic field to cause events called geomagnetic storms.

The Sun's activity fluctuates, reaching a peak every 11 years. In late 2024 the Sun entered the peak of its 11-year solar cycle (also known as solar maximum), which usually lasts for one to two years.

Regardless of the Sun's activity, aurorae can still occur at any time and observers in high latitudes should always look out for them.

How to photograph the aurora

Top tips from Monika Deviat, Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2023 Aurorae winner

"The Northern Lights are a challenge to capture and to see, and it's always a different show every time: you don't know what structures or features will happen. It's fascinating to watch them, and it's fascinating to capture a single moment of the dance.

"When you’re out capturing the Northern Lights, you can't see the colours with your eyes, because you're using your rods in the dark instead of your cones. The camera will capture colours we can't see.

"Finding an interesting location is often what makes an image. When I'm going out to shoot, I usually have a few locations in mind and I'm looking for clear skies.

"Weather is a really big challenge: you can have extreme winds, you can have snow, you can have rain, you can have full cloud. If there's a good opportunity for a show, I'm willing to drive quite a way to find a clear sky window – and it's usually worth it.

Find more stories you might like

Main image: Goðafoss Flow © Larryn Rae, Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2021