Charles I succeeded his father James I in 1625 as King of England and Scotland. During Charles’ reign, his actions frustrated his Parliament and resulted in the wars of the English Civil War, eventually leading to his execution in 1649.

- Charles married the Catholic Henrietta Maria in the first year of his reign. This offended many English Protestants. Charles believed that the heads of the church should be treated with deference. This was a Catholic idea and something that the Puritans did not like.

- He dissolved Parliament when faced with opposition, effectively ruling alone on a number of occasions. In his first four years of ruling he dissolved parliament three times, once for 11 years. He would only reassemble Parliament to raise funds when he ran out of money because of expensive foreign wars.

- He lost popular support over public welfare issues such as the imposition of drainage schemes in The Fens. This affected thousands of people.

- Both his father James I and Charles himself believed in the divine right of kings. This meant that they thought that as King they were above the law, and had been chosen by God.

Trial and conviction

After his defeat by Parliament in the Civil Wars, Charles I was imprisoned. On 20 January 1649 the High Court of Justice at Westminster Hall put him on trial for treason.

Putting a king on trial was a contentious issue. When it came to the trial, those who were against it were turned away or arrested. The remaining parliament was known as the 'rump' parliament.

The King refused to cooperate. He did not enter a plea or recognise the legitimacy of the court. Yet just seven days later, the judges returned a guilty verdict and passed the sentence of execution:

‘This Court doth adjudge that he the said Charles Stuart, as a Tyrant, Traitor, Murderer and Public Enemy to the good people of this Nation, [and] shall be put to death, by the severing of his head from his body’.

For the next three days Charles was kept under house arrest at St James’s Palace. 59 signatures were collected for his death warrant. Politicians pushed through legislation to prevent his son, Charles (later Charles II), from succeeding him. He said goodbye to his two youngest children, Elizabeth and Henry. The Queen, Henrietta Maria, and his two eldest sons were living in exile on the Continent. He took Holy Communion given by William Juxon, Bishop of London.

When was Charles I executed?

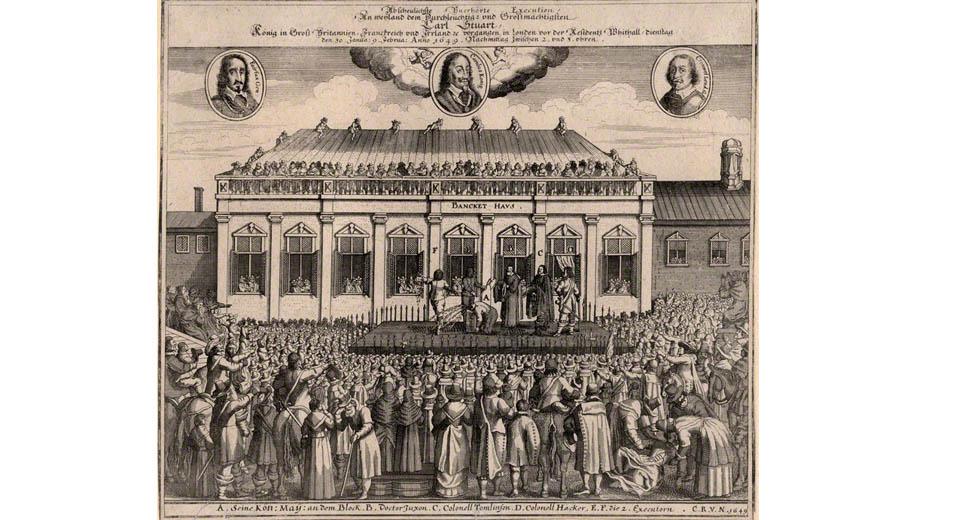

30 January 1649 was a day like no other. Early that winter’s morning, a large crowd of men, women and children assembled in the ‘open street before Whitehall’. They waited in anticipation of an unprecedented event that would shake the nation to its very core. They had turned out to watch the execution of their king.

Where was Charles I executed?

At about ten o’clock, to the beat of military drums, the King was marched by soldiers across St James’s Park to the Palace of Whitehall. On the cold morning of his execution, Charles requested two shirts to wear stating that:

‘The season is so sharp as probably may make me shake, which some observers may imagine proceeds from fear. I would have no such imputation’.

Just after two o’clock he was led into Inigo Jones’s Banqueting House, passing under Rubens’s painted ceiling that glorified his father and monarchy. He was then led out of an upper window onto a specially erected scaffold draped in black. There Charles was met by two heavily disguised executioners, a coffin covered in black velvet, and a low wooden block. He put a cap on his head, tucked his long hair beneath it and prayed with Bishop Juxon once more. He then addressed the crowd, but they were kept at a distance by Parliamentarian troops and could hear very little.

‘I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown; where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world.

He took off his cloak, gloves and garter badge and handed them to the Bishop. He laid his neck on the block and stretched forth his hands as a signal to the axeman that he was ready.

How did Charles I die?

With one blow of his axe the executioner severed the King’s head from his body killing him instantly. A young boy described how the blow of the axe was not met with a cheer but with ‘such a groan as I have never heard before, and desire I may never hear again’.

The King’s head was held up to the crowd. The spectators, some who had watched in approval and some in dismay, were quickly dispersed by officials. A few sought grisly souvenirs of the event rushing forward to dip their handkerchiefs into the royal blood, ‘by some as trophies of their villainy; by others as relics of a martyr’. A week later the monarchy was officially abolished.

Samuel Pepys: Witness to the Execution

Samuel Pepys saw the King’s execution with his own eyes. As a curious 15-year-old, he and some friends played truant from St Paul’s School to watch the gruesome act. Among the bystanders he seems to have been in the Republican camp. Although the occasion pre-dated his diary by some eleven years, the few tantalising words Pepys wrote in his journal, after being reminded of the event by an old school friend, make it clear where his loyalties had been that day:

‘He did remember that I was a great roundhead when I was a boy, and I was much afeared that he would have remembered the words that I said the day the King was beheaded that, were I to preach upon him, my text should be “The memory of the wicked shall rot”. (1 November 1660)

Now, basking in the glow and opportunity of Restoration London, it was wise for Pepys to keep quiet about those Republican sympathies.