Curator Kristian Martin on Samuel Pepys and the Great Fire of London – and how to bury your parmesan cheese...

The Great Fire of London

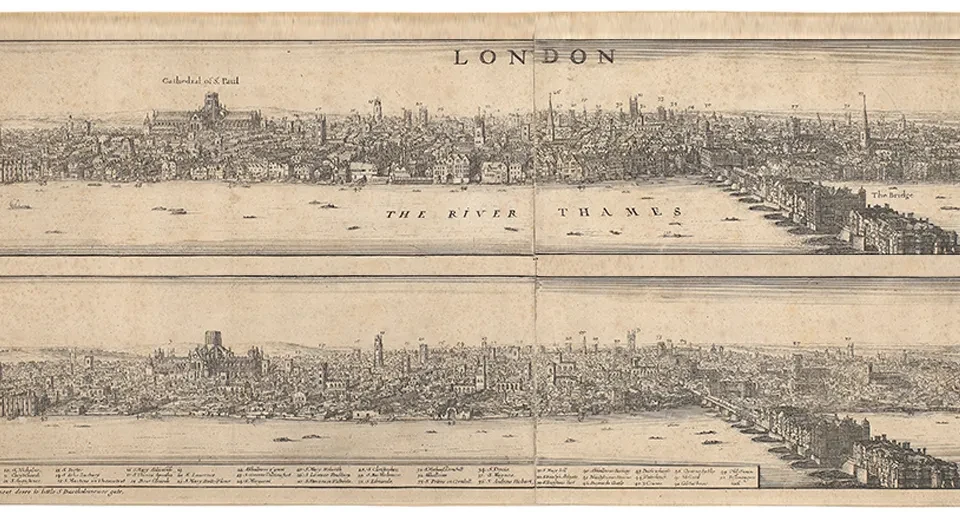

Together with the epidemic of bubonic plague that hit the city the previous year, the Great Fire had an unimaginable impact on London and its people. The fire, which broke out in the house of the King’s baker, Thomas Farynor, early in the morning of Sunday 2 September, decimated four-fifths of the city: over 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, 52 Livery Company Halls, the Guildhall, the Royal Exchange and St Paul’s Cathedral. In the words of Pepys, Medieval London was now ‘all in dust’ – yet would rise from the ashes in spectacular style.

Samuel Pepys’s description of those four days and nights when the fire raged across the city is unmatched. Others recorded in journals, letters and official reports the key events and aftermath, but Pepys’s diary is uniquely human, honest and heartfelt. We can feel Pepys’s frustration at efforts to stop the fire, his panic as he witnesses the flames approaching his home, his desperation in saving his belongings, his sense of duty in protecting his office and his deep concern for the safety of his wife and friends. Above all, Pepys is a Londoner witnessing the destruction of his beloved city: ‘it made me weep to see it.’

Learn more about the Great Fire of London

Samuel Pepys at the centre of things

Like so many big events of the late 17th century, Pepys is at the centre of of the Fire. Rudely awakened by his maid, Jane, at 3 am with news of the distant fire, perhaps unsurprisingly – being used to seeing fires among the densely packed timber buildings of London – he shrugs it off and returns to bed. Realising the seriousness of the conflagration some hours later, it is Pepys who travels to the Palace of Whitehall to tell Charles II that the city is on fire and advises on the pulling down of houses to stop it. Like others, Pepys quickly becomes resigned to the inevitable and his concern turns to himself, his household and his belongings – on the Sunday evening he begins packing, hiding and sending away his possessions which he continues for the following three days. He sends his most valuable things, including the diary, to Bethnal Green, takes his wife and clerk to Woolwich with his remaining belongings and famously buries a valuable round of parmesan cheese in his garden.

In true Pepysian style, the diary also has a knack of candidly chronicling those little details and events about the fire that would otherwise have been lost to history. Pepys records scorched pigeons falling from the skies, people flinging their belongings into the river, a singed cat pulled alive from a chimney, flakes and drops of fire floating across the city, glass melted and buckled by the heat and the ground hot as coals. He also comments on the reaction of others, those exploiting the disaster and conspiracy theories which quickly sprang up about the fire’s cause.