Annie Maunder (1868-1947) was an astronomer, astrophotographer and science communicator.

During her lifetime she made important contributions to numerous areas of astronomy, particularly solar research and astronomy imaging – areas of expertise she developed while working at the Royal Observatory Greenwich.

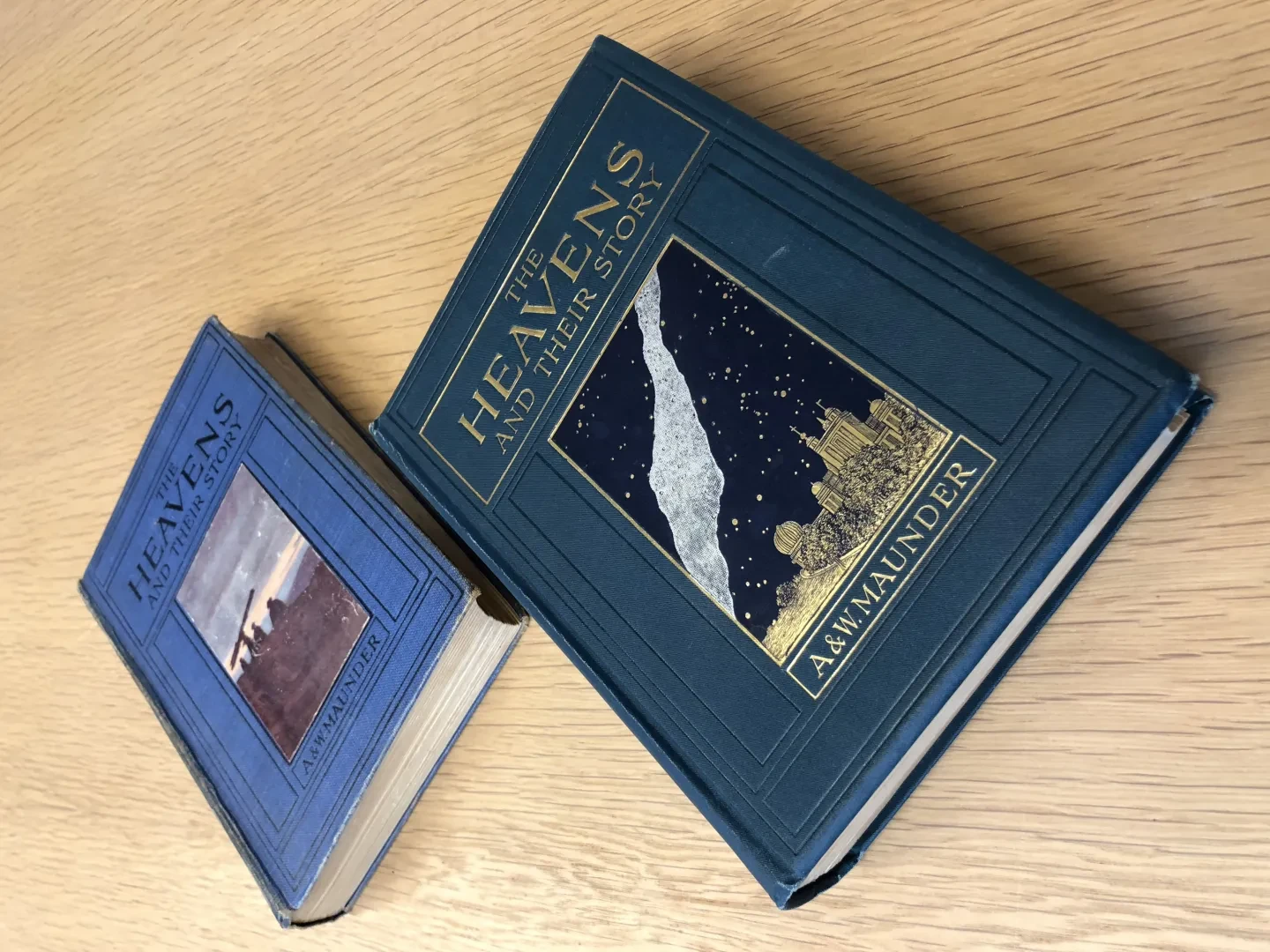

She published magazine articles about astronomy and, most famously, wrote The Heavens and Their Story (1908), which featured some of her innovative images of the Sun.

Read more about Annie’s story, including her entry into astronomy, her partnership with her husband Walter Maunder, and the legacy she left behind.

Early life and education

Annie Maunder (née Russell) grew up in Strabane, Northern Ireland. She was initially educated at home before going to school in Belfast as a teenager.

In 1886 she was offered and accepted an open scholarship to enrol at Girton College, Cambridge to study the Mathematical Tripos.

This college had been set up in 1869 specifically for the education of women. However, despite successfully completing the exams in 1889, Annie and her peers left Girton with no formal recognition, as Cambridge did not award full degrees to women until nearly 60 years later in 1947.

Annie Maunder and the Royal Observatory Greenwich

After first working as a mathematics teacher at a girls’ school in Jersey, Annie heard about the new opportunities at the Royal Observatory through Alice Everett, a fellow Girton College graduate.

The eighth Astronomer Royal William Christie (1845-1922) had started to offer women paid work as ‘computers’. This involved analysing and correcting raw observational data into material that could be published and distributed to other astronomers.

It was painstaking and tedious work that required good mathematical skills, patience and attention to detail, but was rewarded with a pitiful salary.

Although the pay was significantly less than her teaching job, Annie was keen to use her mathematical skills. She joined the Observatory in September 1891.

Astronomy and astrophotography

Despite being called ‘computers’, the young women were not just restricted to purely mathematical tasks. They were also trained on how to use the telescopes.

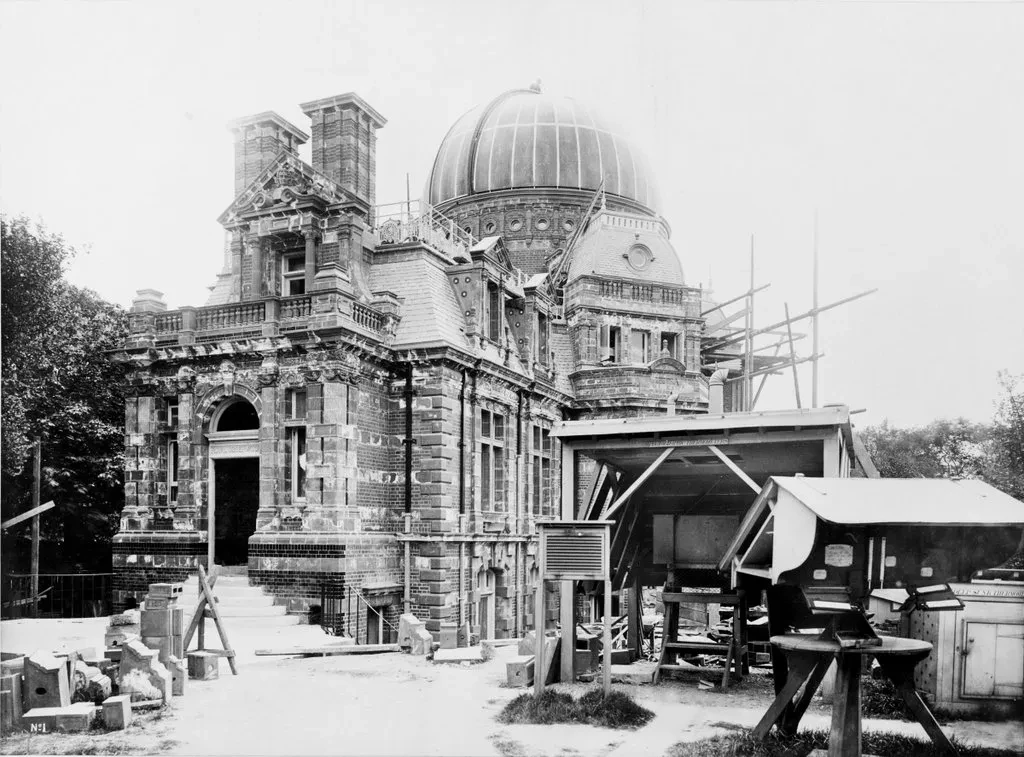

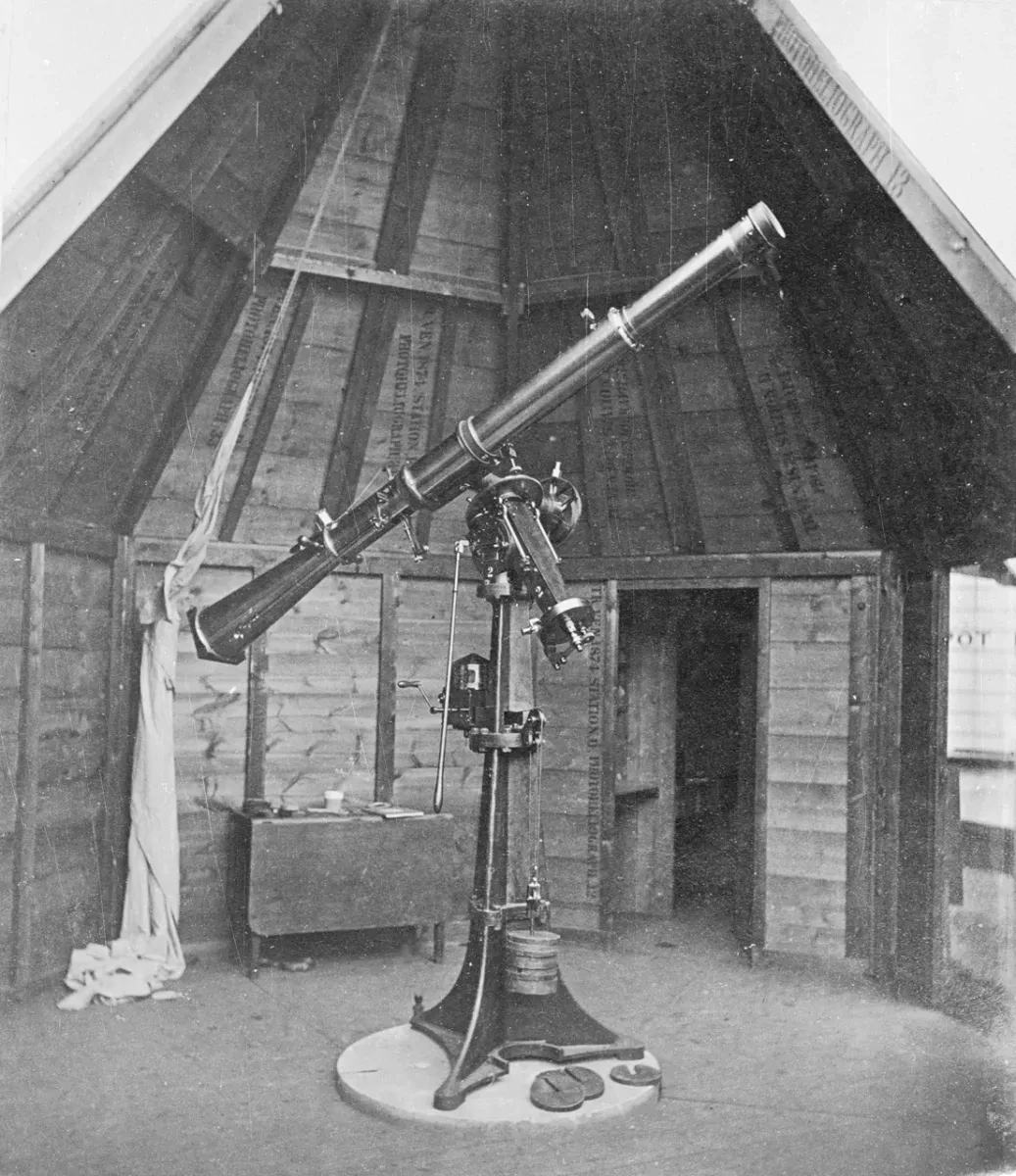

Annie was assigned to work in the Solar Department where she used a Dallmeyer photoheliograph (pictured), one of five specially designed telescopes originally commissioned by the Observatory to view the Transit of Venus in 1874, deployed in various locations including Hawaii and Egypt.

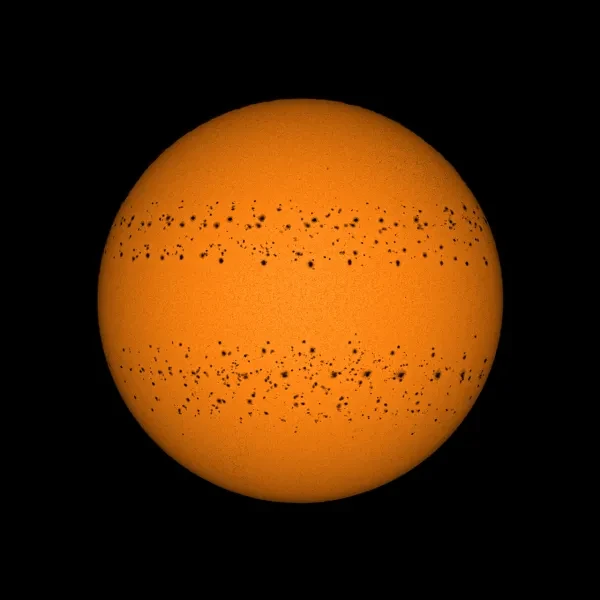

Annie took daily photographs of the Sun to create a record of the changing size and position of sunspots.

Similar photographs were taken at observatories in Mumbai and Mauritius to fill in the gaps during cloudy days in Greenwich, helping to create a complete record of the Sun’s activity.

Edward Walter Maunder

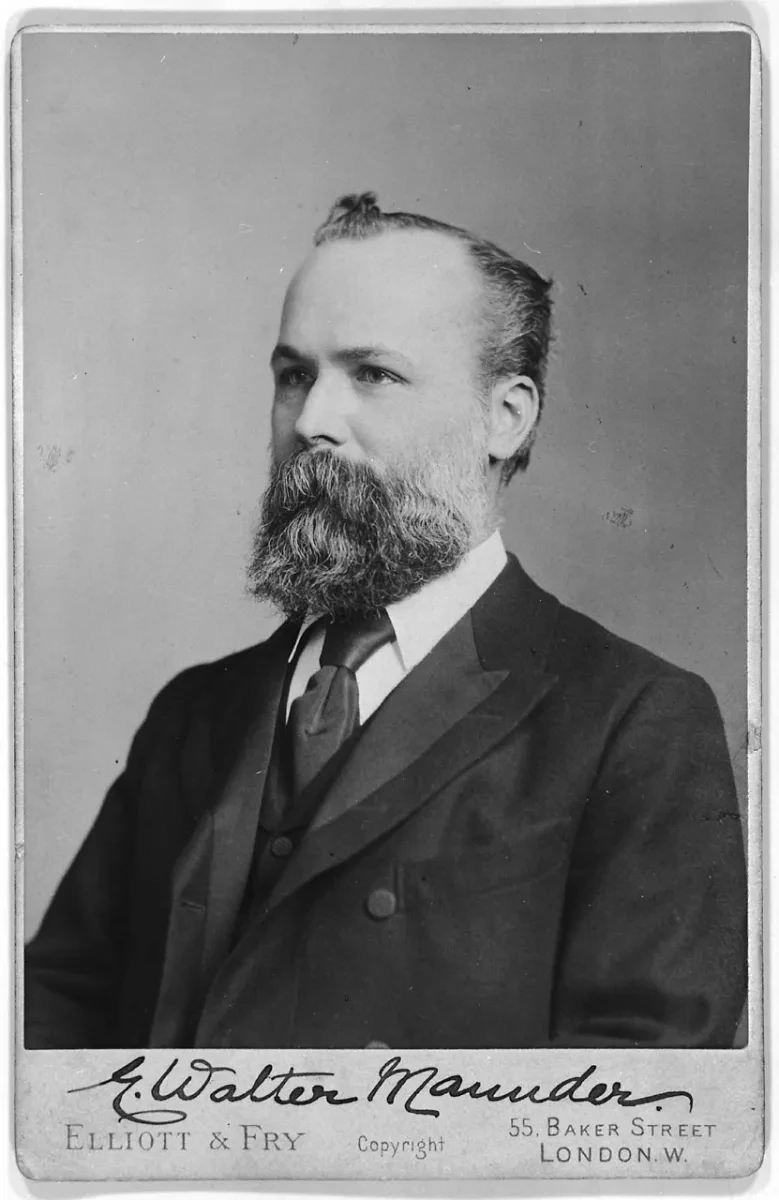

After several years, Anne’s life changed in December 1895 when she married her colleague and the head of the Solar Department, Edward Walter Maunder (1851-1928).

According to rules and social conventions of the day, married women were not permitted to work and so Annie had to resign from her post shortly before her marriage.

Annie continued to participate in astronomy in a voluntary capacity however, particularly through the British Astronomical Association (BAA) which was open to both men and women. She organised solar eclipse expeditions with Walter and the BAA, giving her access to the equipment and resources needed for serious astronomical work.

The couple went on eclipse expeditions to a range of locations including Norway, Algiers and Canada, often using telescopes and specially adapted cameras to capture details of the Sun’s atmosphere.

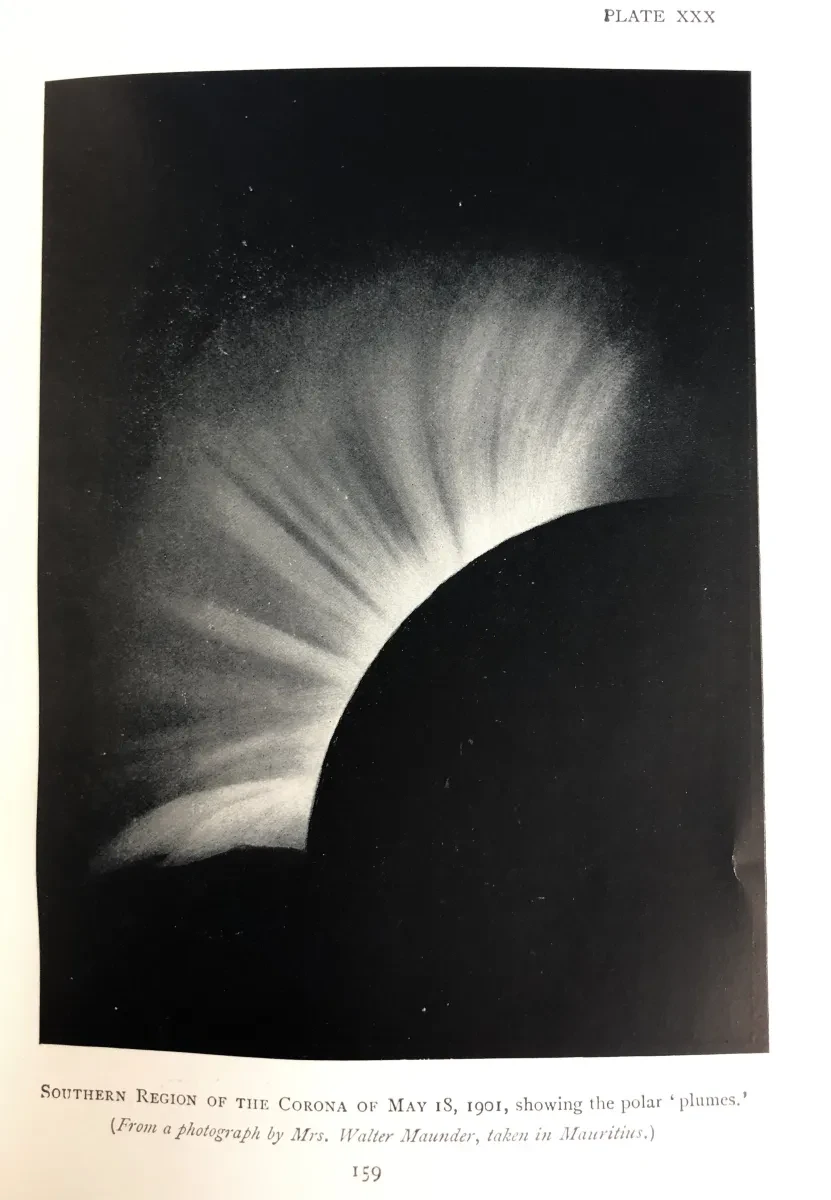

During the brief few minutes of a total solar eclipse, Annie achieved considerable success in capturing images of the sun’s atmosphere.

On 22 January 1898, she photographed an enormous ray-like structure appearing to burst from the Sun: a coronal streamer. She was in India to capture the total solar eclipse, using a wide-angle camera she had adapted herself.

Annie Maunder's work

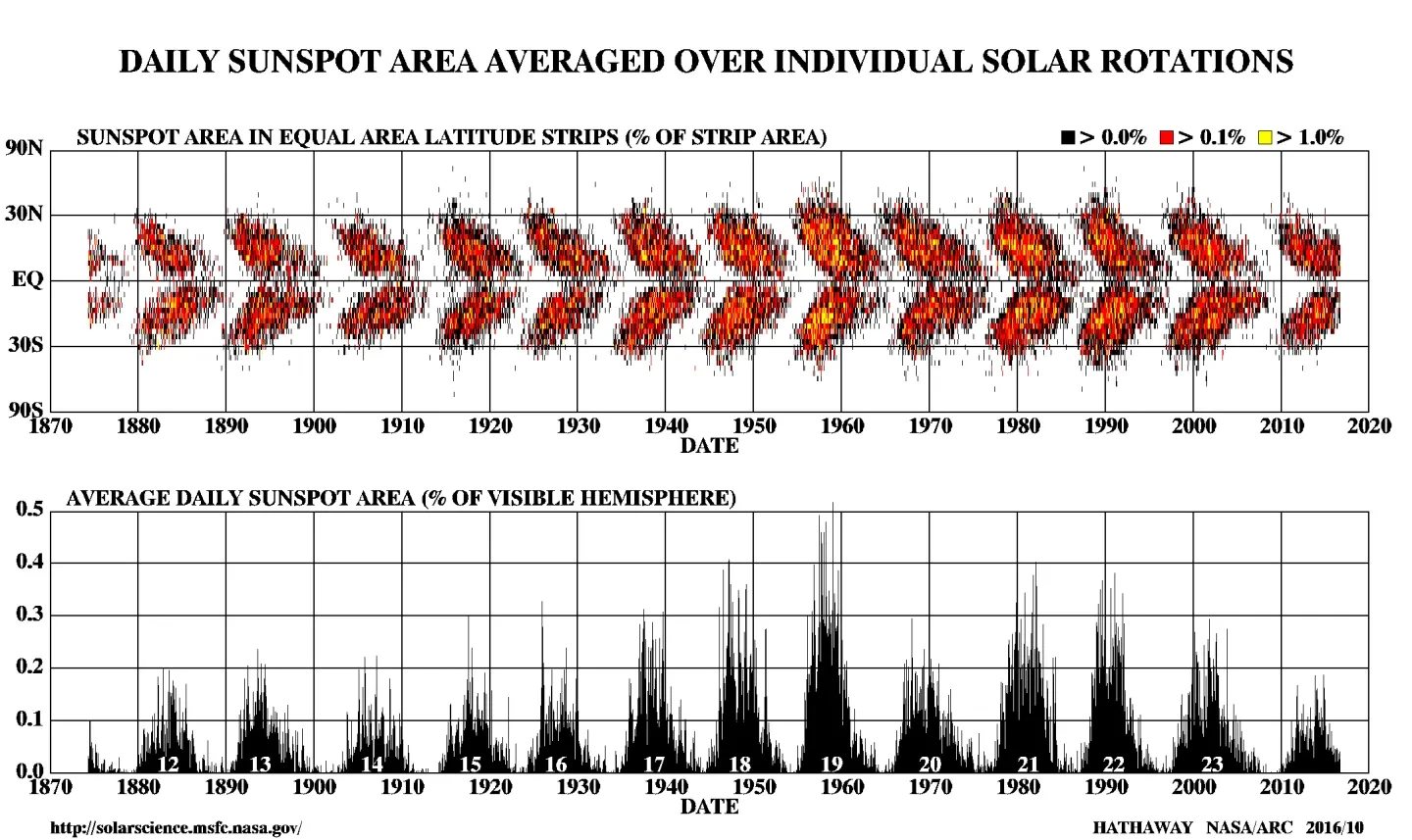

Back in London, Annie and Walter continued to work together on their sunspot data, compiling decades’ worth of observations to create the renowned ‘butterfly diagram’ – a graph that shows how the location of sunspots shifts from high latitudes towards the solar equator over the course of an 11-year solar cycle.

This influential diagram continues to play a role today in helping us understand the nature of the Sun and its complex relationship with Earth.

Despite the lack of opportunities for women and recognition within professional astronomy, Annie was well-known among amateur astronomers as a public lecturer and writer. Among her works is The Heavens and Their Story, first published in 1908 and intended as a practical guide to astronomy.

Although it is credited as being written by both Annie and Walter, Walter commented in the introduction that the book ‘is almost wholly the work of my wife’.

Acceptance into the Royal Astronomical Society

During the First World War, the Maunders returned to fill roles at the Observatory that had been left vacant by staff serving in the trenches.

In 1916, the Royal Astronomical Society admitted women members for the first time; Annie Maunder was one of the first female Fellows.

Walter died in 1928, but Annie lived for almost another 20 years. In later life she redirected her attention towards the history of ancient astronomy, becoming an expert on the origins of the constellations.

Annie Maunder's legacy at the Royal Observatory

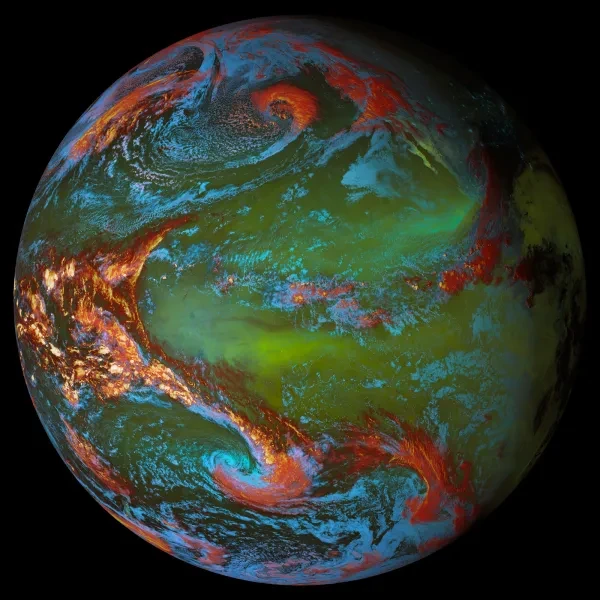

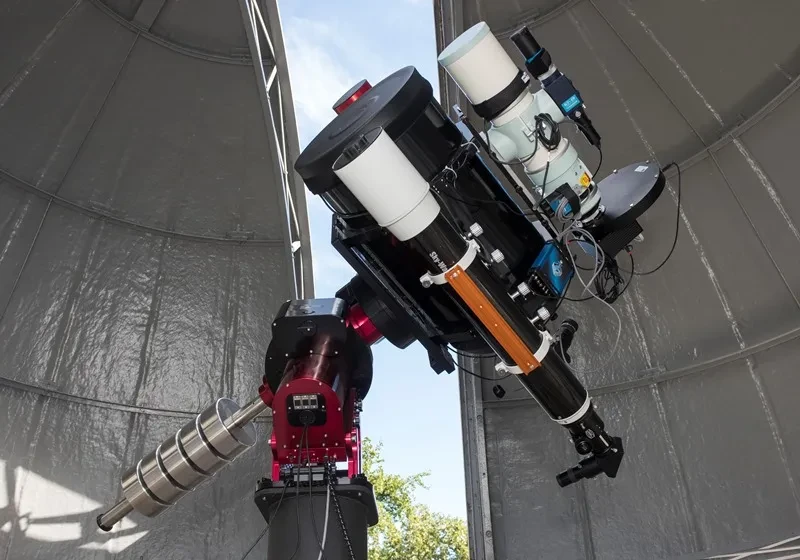

The Annie Maunder Astrographic Telescope (pictured) was installed in the Observatory’s Altazimuth Pavilion in 2018. It can be used to capture high-magnification views of the planets and Moon, safely image the Sun, take filtered images of nebula and supernova remnants, and much more.

There is also a category in Royal Museums Greenwich’s annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition named after Annie. The Annie Maunder Prize for Image Innovation celebrates those who use existing space images to display the wonders of the universe in a fresh light.

Meanwhile, the Royal Astronomical Society awards the Annie Maunder Outreach Medal, given annually to those involved in outreach or public engagement for astronomy or geophysics.

A crater on the Moon is also named ‘Maunder’, dedicated to Annie and Edward jointly. In 2022, Annie and Walter were recognised with a blue plaque at their home in Lewisham, where they lived from 1907 to 1911.