What is the Tea Trade?

While tea had been grown, drunk and traded in China for thousands of years, it only began to be imported into Europe in the very early 1600s. At first, Portuguese and Dutch traders imported it. Until the 1800s, Europeans generally acquired their tea from China and Japan. Trade with China, including tea, was heavily restricted by the government there. Access for foreigners was strictly controlled and the export of the tea plant, for example, was prevented.

Despite these trade restrictions, tea had reached Britain by the 1660s. Across Europe, it had become an expensive but fashionable luxury good, consumed in polite circles. It was imported by the British East India Company, first from secondary markets, and by the early 1700s, directly from China. It was heavily taxed in Britain, and thus remained expensive. However, the smuggling of tea was common and allowed more widespread consumption.

In 1784, the Commutation Act was enacted by the British Parliament. This slashed tea taxes from 119 percent to 12.5 percent, effectively ending smuggling practices. In 1834, the monopoly of the East India Company was ended. This made tea more widely available to consumers across the social spectrum over the following decades. It was also promoted as an alternative to alcohol by the nineteenth-century Temperance movement. By the middle of the 1800s, tea was immensely popular across all levels of British society, and demand was ever-increasing.

Tea and trade in the nineteenth century

By the late eighteenth century, tea was such big business in Britain that there was anxiety about the growing trade imbalance with China, which required payment in silver only.

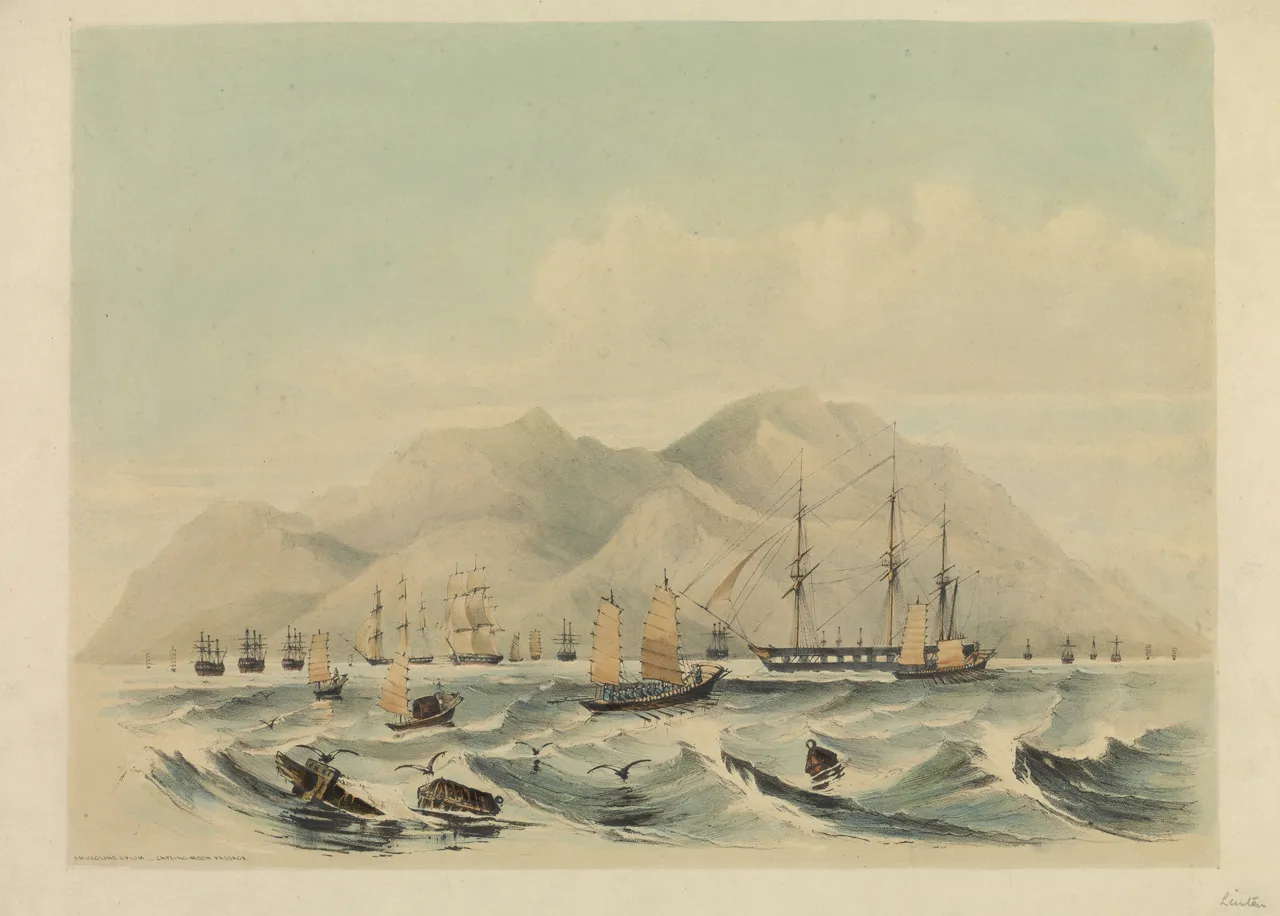

The East India Company, trying to address this imbalance, began to grow and process opium in Bengal to smuggle into China illegally. This ensured the return of some of the silver spent on tea to British coffers.

However, this caused massive addiction problems. The Chinese authorities began seizing opium imports and destroying them. Eventually, this sparked conflict between Britain and China. These are now known as the First (1839-1842) and Second (1856-1860) Opium Wars. The British victories in both wars resulted in, among other demands, Hong Kong being ceded to the United Kingdom, the opening of five ports to foreign trade, and a relaxation of restrictions on foreign access to inland China. This damaged the size and impact of the Chinese economy worldwide for some time.

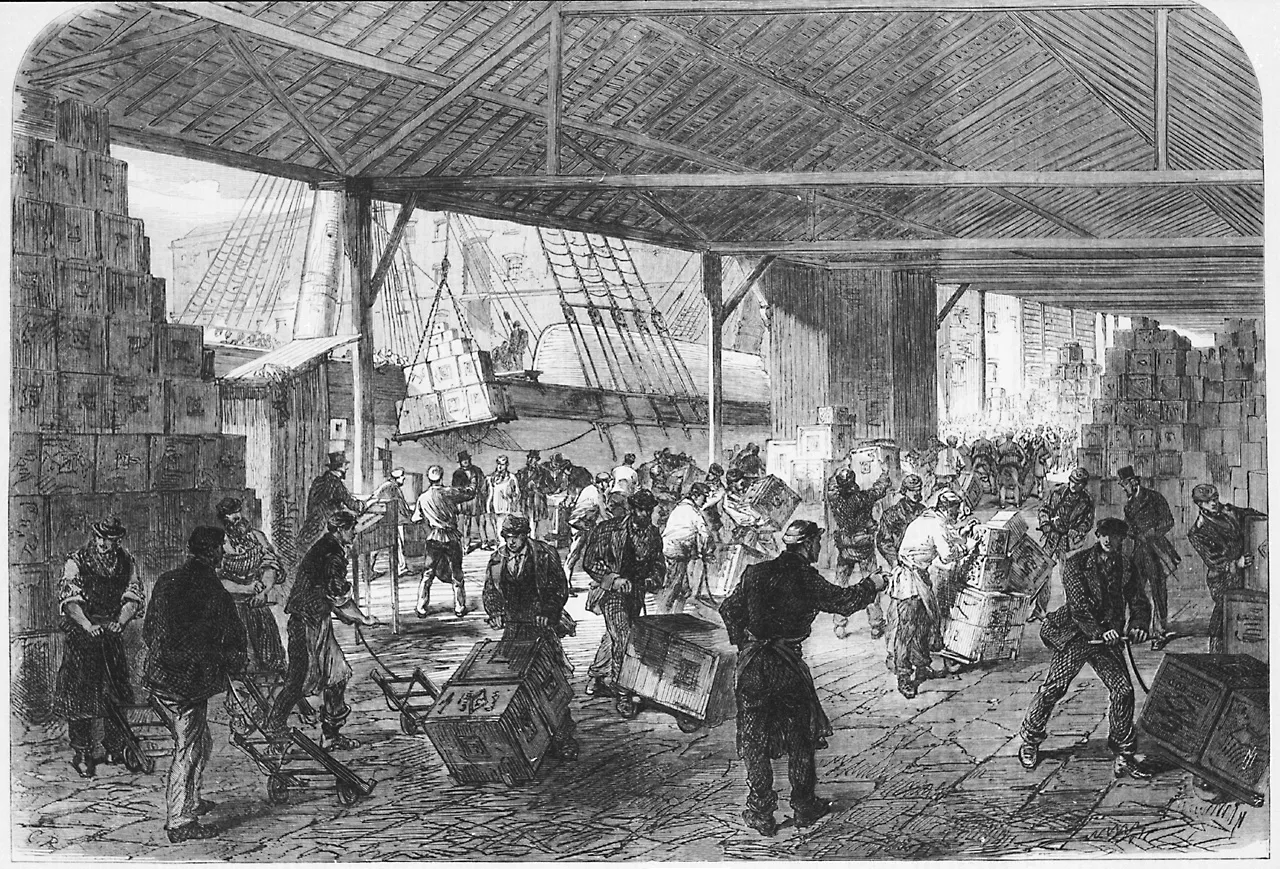

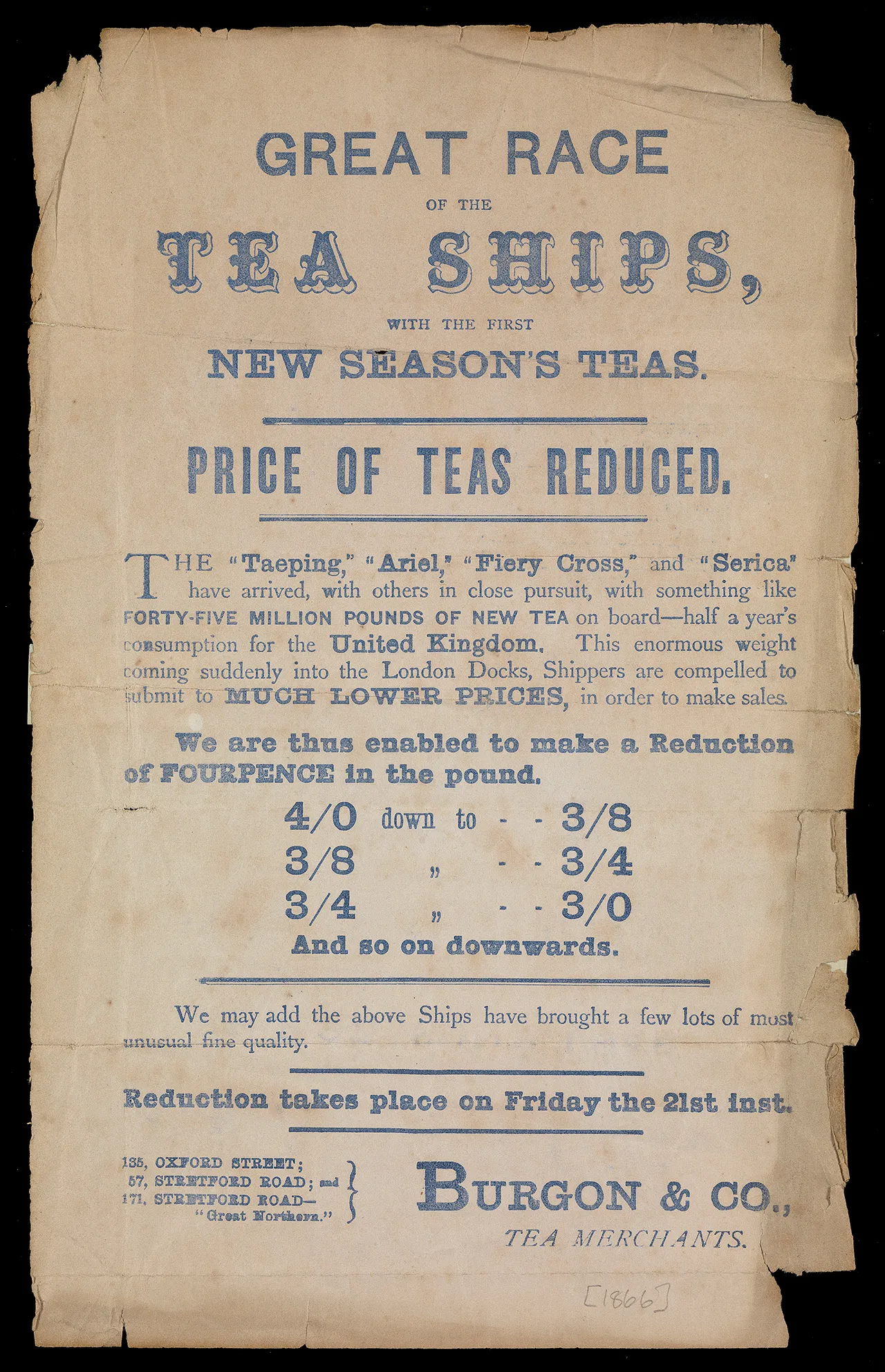

It was in the aftermath of these wars that the tea trade expanded substantially from the 1860s. New ports opened along the Chang Jiang (Yangtze) river, including Hankou, the tea capital of China. This increased the supply of tea and prompted a fashion in Britain for ‘fresh’ tea, the first crop of the year. This resulted in tea races, with clipper ships, built for speed, vying to be the first ship into port in London carrying a tea cargo. Premiums of 10 shillings per ton were paid on the winning ship’s cargo, so competition was fierce. It was in this climate that Cutty Sark was built and launched.

Cutty Sark and the tea trade

John Willis commissioned the building of Cutty Sark at a time of intense rivalry in the tea trade. This was based almost entirely on the ability to travel to China and return to London with your cargo as quickly as possible. Clipper ships were built for speed, and Willis wanted his Cutty Sark to be the fastest cargo ship afloat. The hull was a composite, made of teak and rock elm attached to a light and streamlined iron skeleton, while a sharp bow and narrow hull ensured the ship was dynamic in the water. The ship was built with extremely tall masts, a vast sail area and wire, rather than rope, rigging. This was all designed to increase speed at sea, and a steering mechanism that freed up valuable cargo space in the hold. Cutty Sark was designed and built, from top to bottom, to win the tea races. Cutty Sark could hold around 10,000 tea chests, which would have had a value of around £6 million in today’s money.

However, the great value placed on speed in the tea trade would ultimately cause problems for Cutty Sark and John Willis.

Despite being built in 1869 as a tea clipper, the Suez Canal opened in the same week. This reduced the journey between Britain and China by around 3000 miles for the steamships that were allowed to use it.

Very soon, sailing ships like Cutty Sark were no longer competitive in the tea trade, which relied so heavily at that time on speed and efficiency. Cutty Sark completed eight voyages to China carrying tea. It was eventually repurposed into lower-value, but still essential, trade routes, carrying wool from Australia to the mills of industrial Britain.