In this blog we explore the remarkable life of Charles Todd, a Greenwich astronomer who championed Australia's Overland Telegraph Line

Galvanic Connections between Greenwich and Australia

On 22 August 2022 we’re celebrating a fantastic achievement, namely the 150th anniversary of the completion of Australia’s Overland Telegraph Line in August 1872.

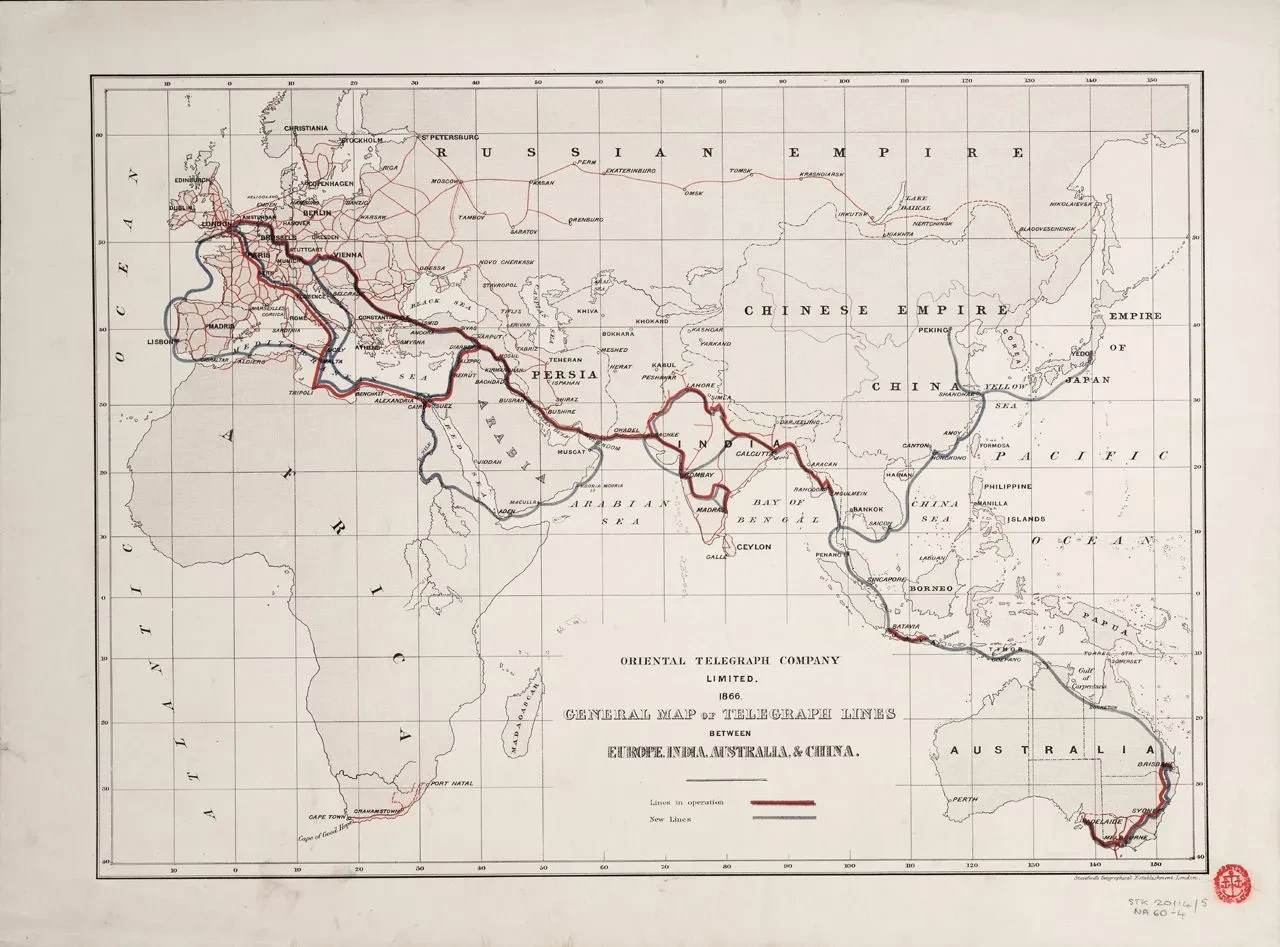

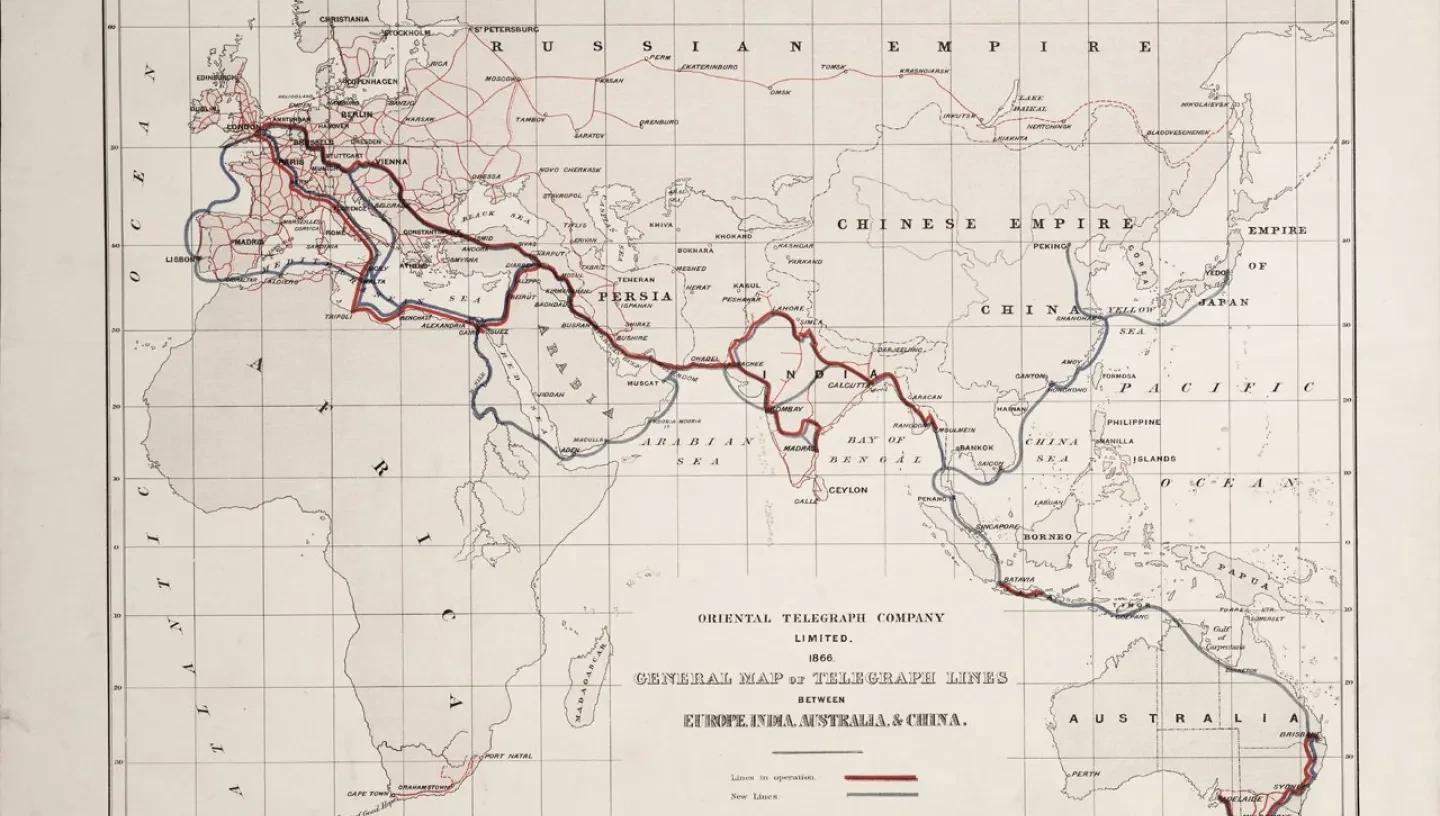

This ambitious project not only connected the cities of Adelaide and Darwin to each other but also enabled Australians to become part of the global telegraph network.

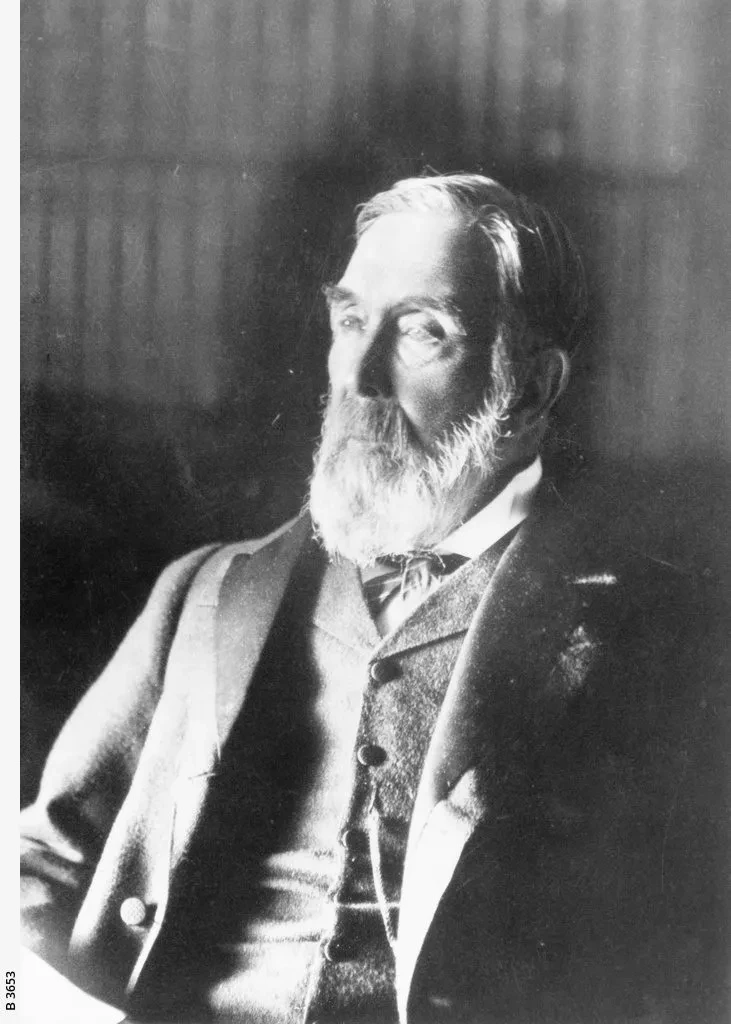

The man who championed this endeavour was Charles Todd (1826-1910), an astronomer from Greenwich who emigrated to Australia in the 1850s and went on to play a pivotal role in the growth of telegraph stations and meteorological observatories across the country.

Senior Curator Dr Louise Devoy explores the invisible story that links British and Australian observatories over 10,000 miles (16,000 km) apart.

Charles Todd's early years in Greenwich and Cambridge

Charles Todd was born in Islington, north London, on 7 July 1826 but spent his formative years in Greenwich. At the age of 15 he was recruited as a ‘Boy Computer’ by the Astronomer Royal, George Biddell Airy (1801-1892) to help correct our predictions of the Moon’s orbit by analysing historic observations made at Greenwich from 1750 to 1830.

Todd and his fellow ‘computers’ – around ten other local teenage boys – worked steadily in the Observatory’s Octagon Room from 8am to 8pm several days a week and the resulting ‘Lunar Reductions’ project was subsequently published in 1848.

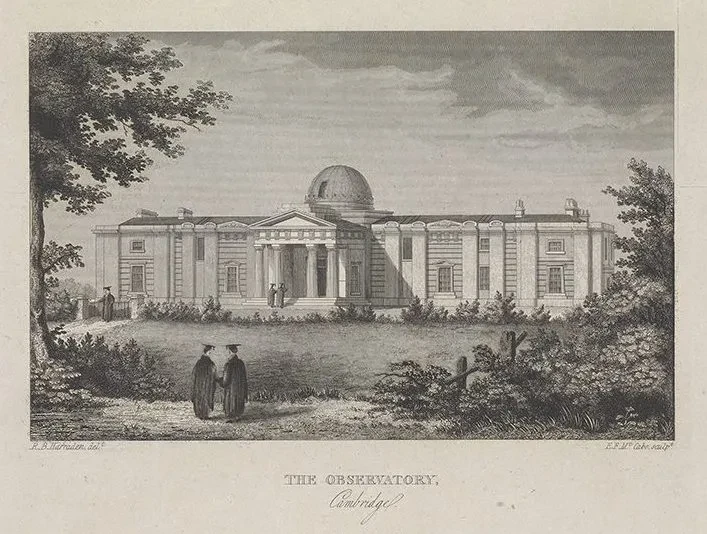

It was tedious work but Todd persevered until 1847 when he was recommended by Airy for the post of Junior Assistant at the University of Cambridge Observatory, the same institution where Airy had begun his own career nearly two decades earlier.

Now a young man in his early twenties, Todd took advantage of his new role to gain valuable experience in using telegraph signals (‘galvanic systems’) to compare simultaneous observations between Greenwich and Cambridge, allowing astronomers to calculate the difference in longitude between the two observatories.

He also experimented with the burgeoning technique of photography to create the first daguerreotype of the Moon, as seen from England, and he used the Northumberland Telescope to make early observations of the planet Neptune, discovered just a few years previously in 1846.

Getting to grips with telegraphy

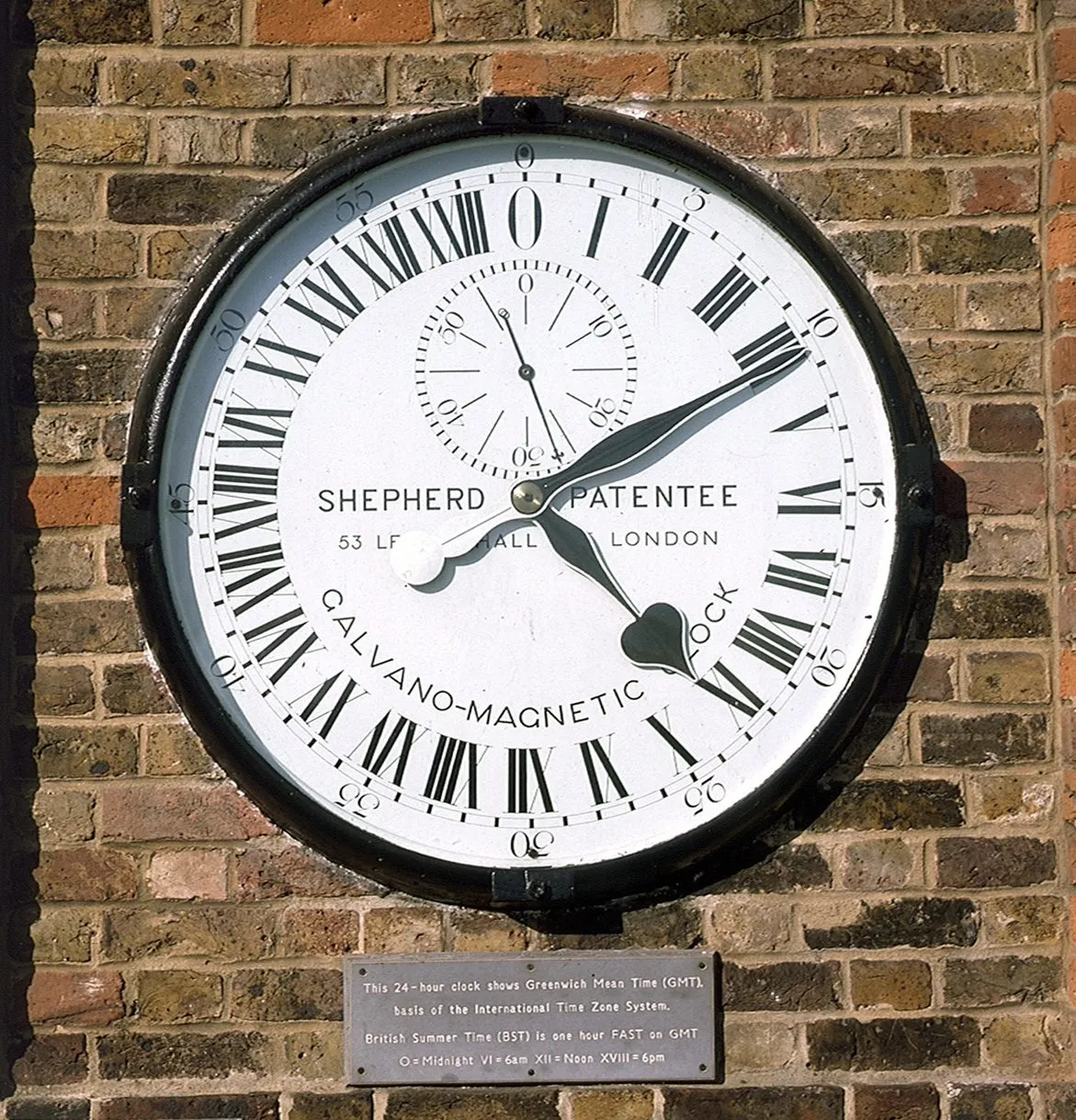

Armed with this technical experience, Todd returned to Greenwich in May 1854 to become part of the newly-formed Galvanic Department. Three years earlier, Airy had seen a new type of clock at the Great Exhibition that could be used to distribute Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) to a much wider network of users.

Designed by the London clockmaker Charles Shepherd, the electric motor clock sent galvanic impulses every second to a series of ‘sympathetic’ dials that kept perfectly in sync. Airy realised that he could use Shepherd’s invention to distribute GMT across the country via the growing telegraph and railway networks.

The new system was installed in August 1852, with the motor clock situated within the north-east summerhouse of Flamsteed House and a series of sympathetic dials installed at various locations around the site. One of the dials was embedded into the wall next to the Observatory gates to provide GMT for the public.

Todd’s new role involved him diverting some of the time signals from the motor clock to drop both the Observatory’s own time-ball and others installed at the Electric Telegraph Company (London) and on the coast at Deal (Kent).

Just over six months later, Airy was asked by the Colonial Office to recommend someone for the post of Superintendent of Telegraphs and Government Astronomer of Southern Australia. After initially offering the job to another assistant, Airy offered the post to Todd who now had the essential observational and telegraphic skills from his experience at Cambridge and Greenwich.

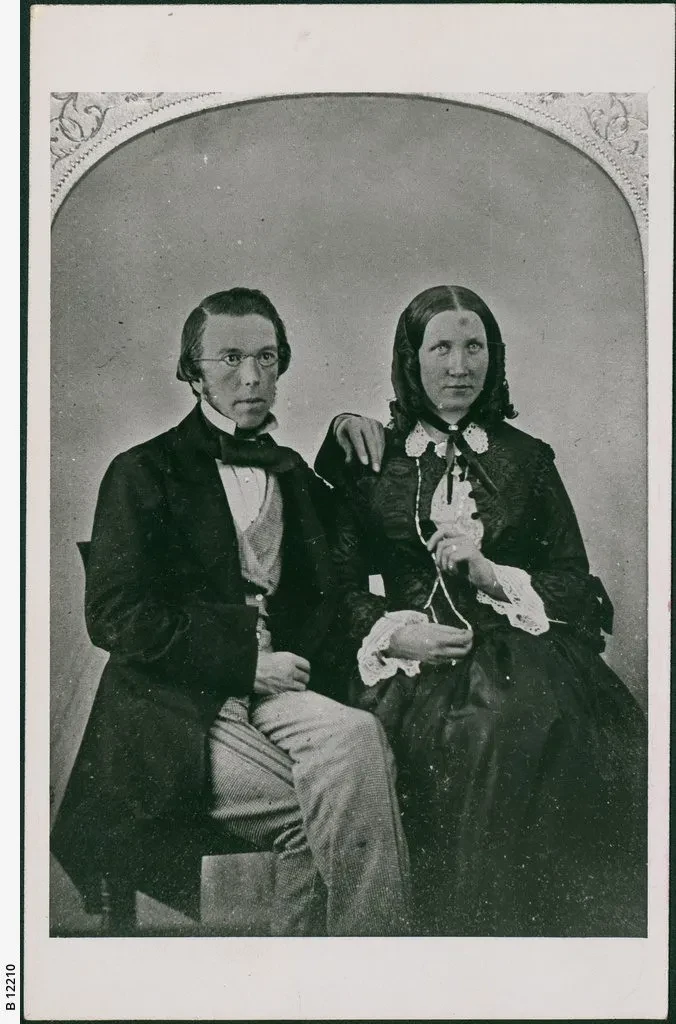

It was an attractive offer with much better pay and so Todd returned to Cambridge to marry his sweetheart Alice Gillam Bell (d.1898) before sailing to Australia and arriving in Adelaide on 4 November 1855.

Connections within Australia

Todd’s first decade in Australia was focused on creating telegraphic connections between the cities of Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney. He also used the emerging network of telegraph stations as a means of recruiting and training postal officials as meteorological observers who could send data back to Adelaide.

At the same time, Todd created Adelaide Observatory (since demolished) with an impressive array of astronomical and meteorological instruments.

But it was the growing demand for a trans-national and ultimately international telegraphic connection that consumed Todd’s workload. After decades of political wrangling, the necessary funds and agreements were in place by 1870 to create a north-south link between Adelaide and Darwin that could provide a direct telegraphic connection to England via Singapore and India.

Todd used the surveys undertaken by John McKinlay (1819-1872) and John McDouall Stuart (1815-1866) to plot the 1,800 mile (km) route, inspecting some sections for himself and relying on camels and waggons to transport the telegraph apparatus to the remotest locations. The Overland Telegraph Line was eventually completed on 22 August 1872 at Central Mount Stuart and the undersea connection across Asia to England was completed a few months later.

This technological marvel enabled Australians to transmit messages to London in just 5 hours, rather than 4 months via mail steamer ships – what a fantastic achievement for Todd and his team!

Legacy

Although Todd went on to achieve great success in many other scientific endeavours within meteorology and astronomy, it’s the Overland Telegraph Line that remains his most famous achievement.

In a curious twist to the story, one of the telegraph repeater stations in central Australia was named after Todd’s wife Alice in 1870.

Several decades later, the adjacent settlement of Stuart was re-named Alice Springs and the historic telegraph station is now preserved within a national park area, more details are available here.

Find out more online

G. Dolan, ‘People: Charles Todd’, royalobservatorygreenwich.org/articles.php?article=1112

G. W. Symes, 'Todd, Sir Charles (1826–1910)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, adb.anu.edu.au/biography/todd-sir-charles-4727/text7843, published first in hardcopy 1976, accessed online 19 July 2022.