In this blog we explore how our ancestors obtained ice in an age before widespread domestic refrigeration.

Nowadays we take refrigeration for granted; equally, we probably assume that our ancestors had to make do without it except in the depths of winter. If so, we would be wrong. Our ancestors had ice for their drinks and for keeping food cool, and our Victorian ancestors could even buy ice cream from sellers in the street. So how were they able to do this? Where did the ice come from and how were they able to keep it frozen?

Ice was harvested from ponds, rivers and lakes and stored in ice houses for use such as conserving food. Ice houses still survive today in various locations. They are well-insulated, predominantly subterranean structures usually located close to the source of ice. The ice could be packed inside so that its surface area was comparatively small, and it thawed slowly. A hole in the base of the structure allowed the water from thawed ice to escape, but the thawing process could take many months or even in excess of a year. King James I commissioned an ice house for Greenwich Park in around 1620.

Importing ice

Ice began to be imported into Britain in the 19th century. In the United States, Bostonian Frederick Tudor had started the ice trade at the beginning of the century and grew rich on the proceeds. Uniform blocks could be cut using ice ploughs, and the ice shipped nationally and even internationally to countries in the West Indies and the Caribbean.

A little later, businesses based in Boston exported ice to Calcutta, where it was bought by the British who were based there. The holds of the ships carrying the ice were insulated with materials such as sawdust and hay, and in this way it was possible for ice to be transported across vast distances.

The ice trade grew and other ice merchants joined in. Jacob Hittinger harvested ice from Fresh Pond in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His company Gage, Hittinger & Co. first exported Fresh Pond ice to London in 1842. Salem-based Charles B. Lander started harvesting ice from Wenham Lake in Maine. The first English-bound shipment of ice from Wenham Lake arrived in Liverpool on the ship Ellen in 1844.

The Wenham Lake Ice Company had their British headquarters in the Strand in London, where they displayed a two-foot square ice block in their window during the summer months. The satirical magazine Punch, in its issue of 14 June 1845, could not resist making fun of the enterprise:

A concern has lately started in the Strand, under the title of the Wenham Lake Ice Company. The stock of the company appears to consist of large blocks of ice, so that great care must be taken not to melt the whole of the capital.

While Punch may have found the enterprise amusing, it appears the company may have had the last laugh. Deliveries left the site twice daily and a block of ice was even sent to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Windsor.

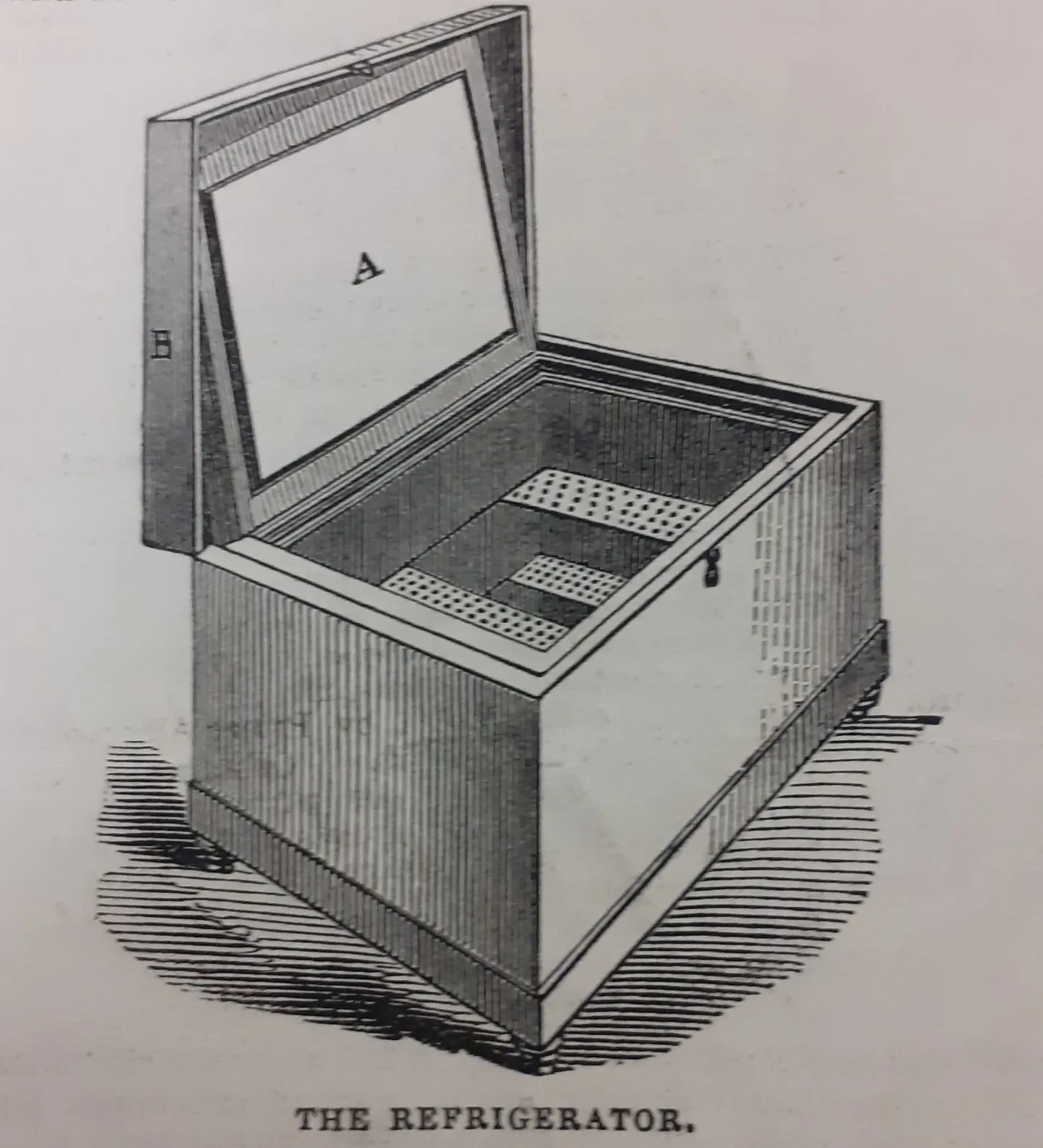

Wenham Lake Ice Company also offered refrigerators for sale. These were metal-lined wooden boxes for storing food. Inside, they were fitted with shelves. The refrigerators were kept cool by being replenished with regular deliveries of ice and by being well sealed. The Illustrated London News of 17 May 1845 published an image of the type of ‘Refrigerator, or portable ice house’ then in use in American homes.

Harvesting ice

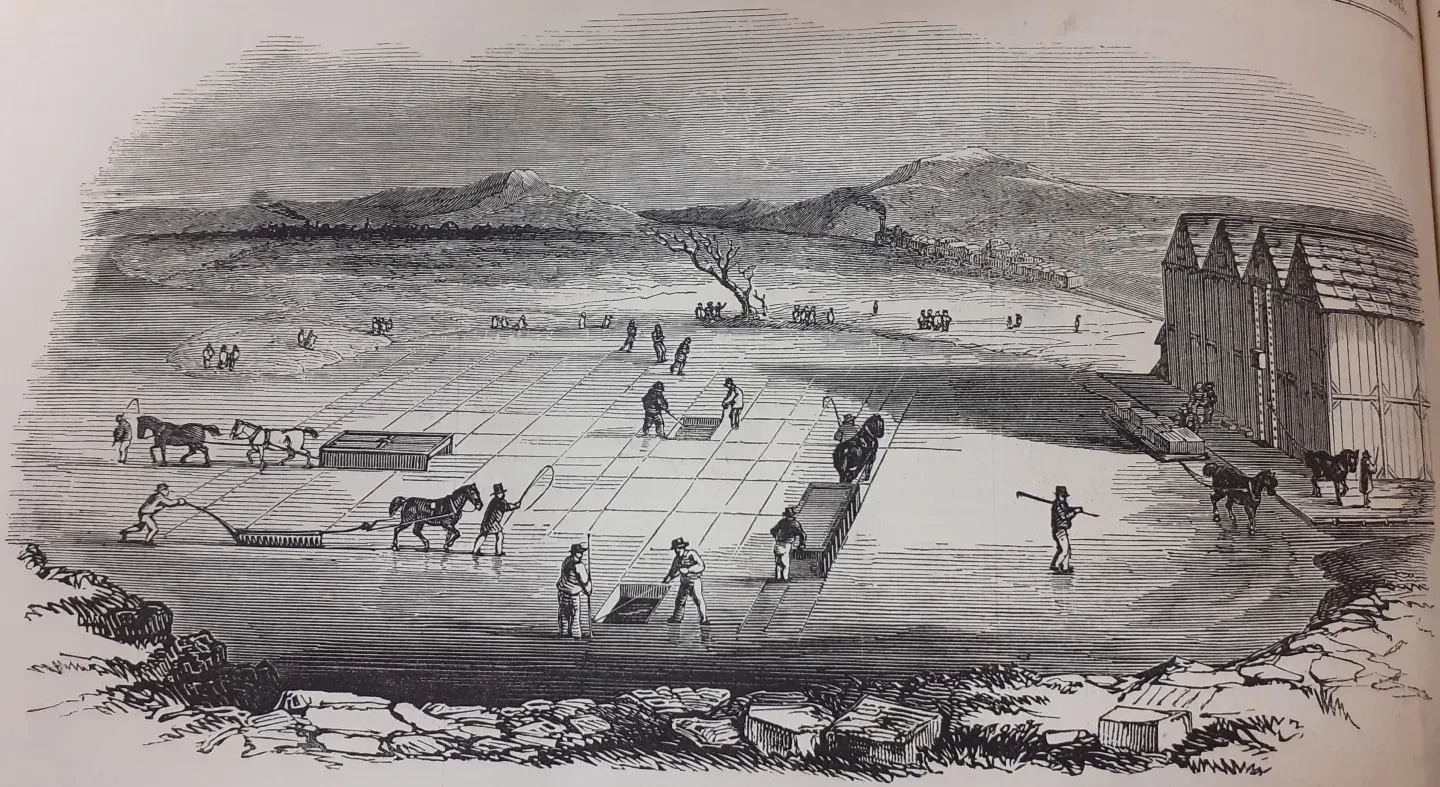

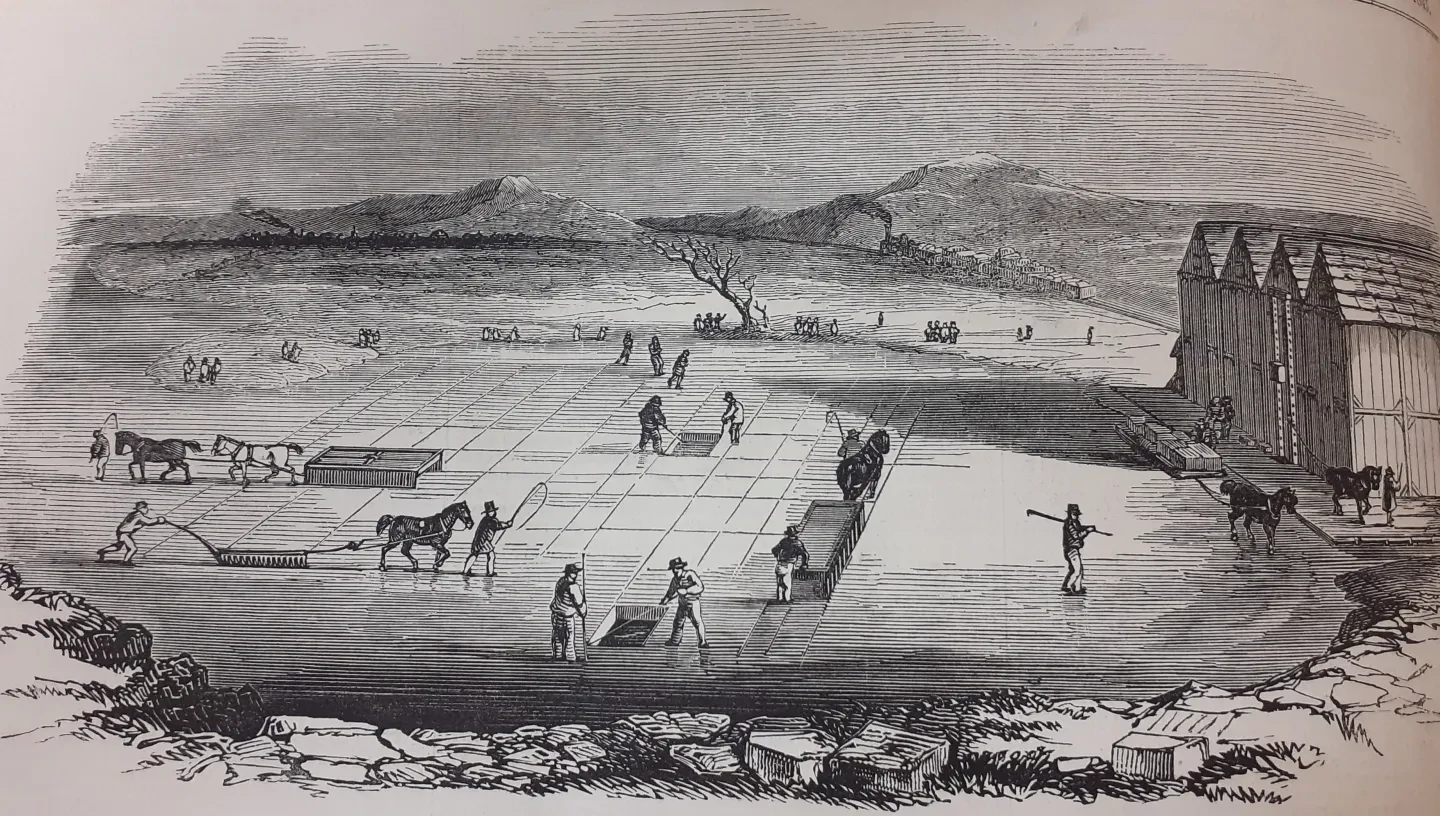

In the same article, The Illustrated London News described the set-up at Wenham Lake and went into some detail about how the ice was harvested. It noted that, in contrast to the ‘occasional and fitful’ nature of ice collection in Britain, the harvesting of ice in America could

be regularly carried on through the whole winter; while the adjuncts of machinery for cutting and storing, and of steam for transporting it, are brought extensively into action.

The ice was cut by ‘machinery […] invented for that express purpose’ and was ‘worked, by men and horses’.

The article further reported that the storehouse at Wenham Lake could accommodate ‘20,000 tons of Ice’ and that the company had its own railway which connected ‘with the great railway to Boston.’

Norwegian ice began to be shipped to Britain in the 1820s, but the trade really developed from the 1850s. Initially the ice was cut from the lakes during the spring and loaded onto ships, but storage, in the form of ice houses, was soon built so that it was possible to transport the ice during the summer and autumn months as well. Norwegian ice exported to Britain was cheaper than Wenham ice and could out-compete it. The Wenham Lake Ice Company, the pioneer of exporting ice to Britain, began to focus more on its domestic market.

Ice cream

Besides helping to store food, ice was also used for making ice cream. Street sellers began selling ice cream comparatively early in Queen Victoria’s reign.

A Swiss Italian named Carlo Gatti (1817-1878), who settled in Holborn, London, in 1847, was one of the earliest sellers of ice cream. He sold ices and other eatables from a stall in Hungerford Market (close to where Charing Cross railway station is today). At least some of his ice came from the Regent’s Canal.

According to the Victorian journalist Henry Mayhew (1812-1887), who was writing when the selling of ice cream in the streets was very new, the ice-cream trade was not always profitable to begin with. He mentions one man who

sometimes went himself, and sometimes sent another to sell ice-cream in Greenwich Park on fine summer days, but the sale was sometimes insufficient to pay his railway expenses. After three or four weeks’ trial, this man abandoned the trade, and soon afterwards emigrated to America.

Customers trying ice cream for the first time could be surprised by its effect. One street seller to whom Mayhew spoke told him:

Lord! how I’ve seen the people splntter [sic] when they’ve tasted them for the first time. I did as much myself. They get among the teeth and make you feel as if you tooth-ached all over.

The seller told Mayhew about two of his customers, a servant maid and her man:

I knew one smart servant maid, treated to an ice by her young man—they seemed as if they was keeping company—and he soon was stamping, with the ice among his teeth, but she knew how to take hern, put the spoon right in the middle of her mouth, and when she’d had a clean swallow she says: ‘O, Joseph, why didn’t you ask me to tell you how to eat your ice?’

From those small beginnings, a larger business grew.

Britain continued to import naturally-produced ice into the 20th century, when artificial refrigeration eventually took over.

Sources for researching the ice trade

‘Ice’, in The Illustrated London News, Vol. VI, No. 159. London, 17 May 1845, p. 315-16 (RMG ID: ILN).

Henry Mayhew, London labour and the London poor. Griffin, Bohn, and Company, London, 1861 (RMG ID: PBF5076). The ice cream sellers are described in volume 1.

D. V. Procter, Ice carrying trade at sea: the proceedings of a symposium held at the National Maritime Museum on 8 September 1979, Maritime monographs and reports no. 49. Trustees of the National Maritime Museum, London, 1981 (RMG ID: PBN4801).

Gavin Weightman, The frozen water trade: how ice from New England lakes kept the world cool. Harper Collins Publishers, London, 2003 (RMG ID: PBF3781).