Former Caird Fellow Dr. Jack Avery explores the seventeenth-century maritime journals held at the Caird Library and Archive, and in particular the one written by the amateur poet and astrologer Jeremy Roch

Would you sail into the thick of battle even if you knew that you were doomed to fail? What if there was incontrovertible evidence that you would succeed? ‘All things are ordered from Above | By the Stars influence, & that by Jove’, rhymed the Plymouth seafarer Jeremy Roch in his handwritten journal of his adventures at sea (RMG ID: IGR/17).

Roch had endured much, including naval warfare, piracy, shipwreck on the Dutch coast, and a French passenger who ate all his victuals in one sitting. He had lost track of at least two dogs during these accidents, as well as several boys. Roch penned his stories with an eye to entertaining friends and family, and they have the distinct feeling of already having been often told, such as his account of a ‘Dutch dinner’ of ‘smoked beef, or horseflesh perhaps; a great dish of chopped cabbage, raw, instead of a salad… and for a drink a sort of beer brewed with water of the Stygian Lake’.

However, we would be wrong to take these as little more than a series of picaresque tales that got ever longer in the telling. Roch was an amateur astrologer as well as a writer – his friend the ship’s doctor James Yonge even described him as an ‘ingenious astrologer’ in his own journal – and this collection of his adventures was designed to provide firm evidence, once and for all, that astrology actually worked. He would show that all his fortunes and misfortunes could be correlated to the movements of the heavens.

Roch celebrated this project in an introductory poem to Urania, the muse of astrology, promising that he would:

Observe thy Motions, & thy Aspects Ken,

That I may show to the dull sons of Men,

How hapines, how Wo’s com, or commence

From well or ill dispos’d Stars influence.

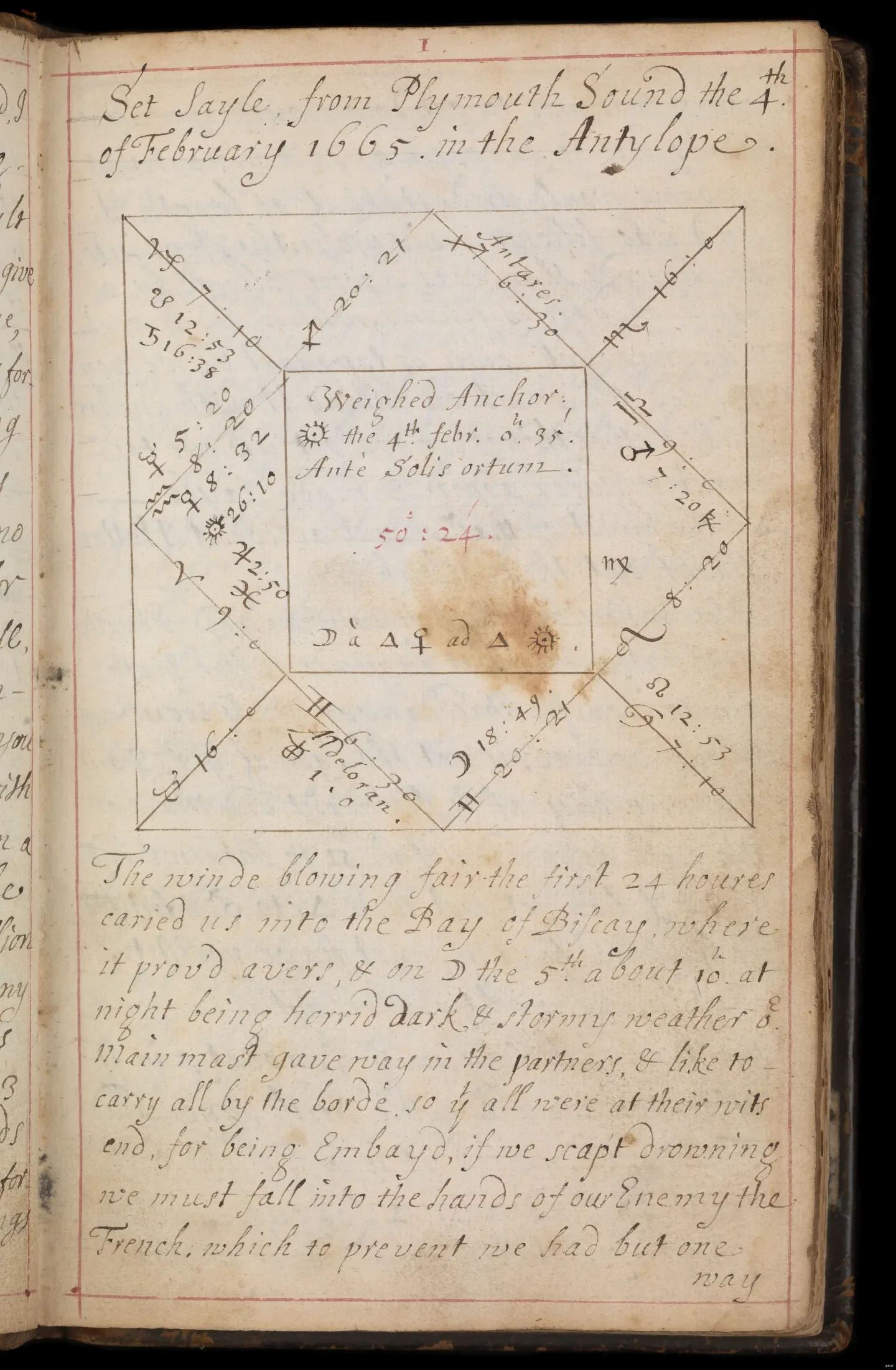

As a result, Roch’s journal is packed with astrological projections, intricately-ruled diagrams which combined astronomical observations of the heavens with mathematics and ancient wisdom.

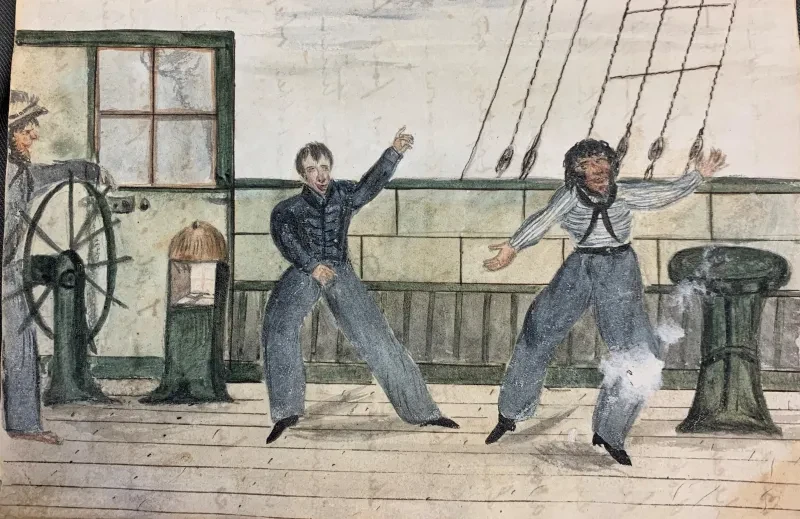

In the centre, he often put his practised mariner’s hand to use drawing a colourful depiction of whatever event was being augured. These are often immediately recognisable, with ships piled on top of one other amid the chaotic brawl of the Four Days’ Battle, or lined up in a stately parallel for the St James’s Day Fight.

I was intrigued by these curious diagrams during my recent fellowship investigating the many journals kept by the Caird Library, and impressed by Roch’s deft combination of poetry, technical astrological skill, and visual artistry. While each of these skills are often found in other mariners’ journals, Roch blended them together into a uniquely individual manuscript that manages to entertain while also being an exercise in scholarly data-gathering.

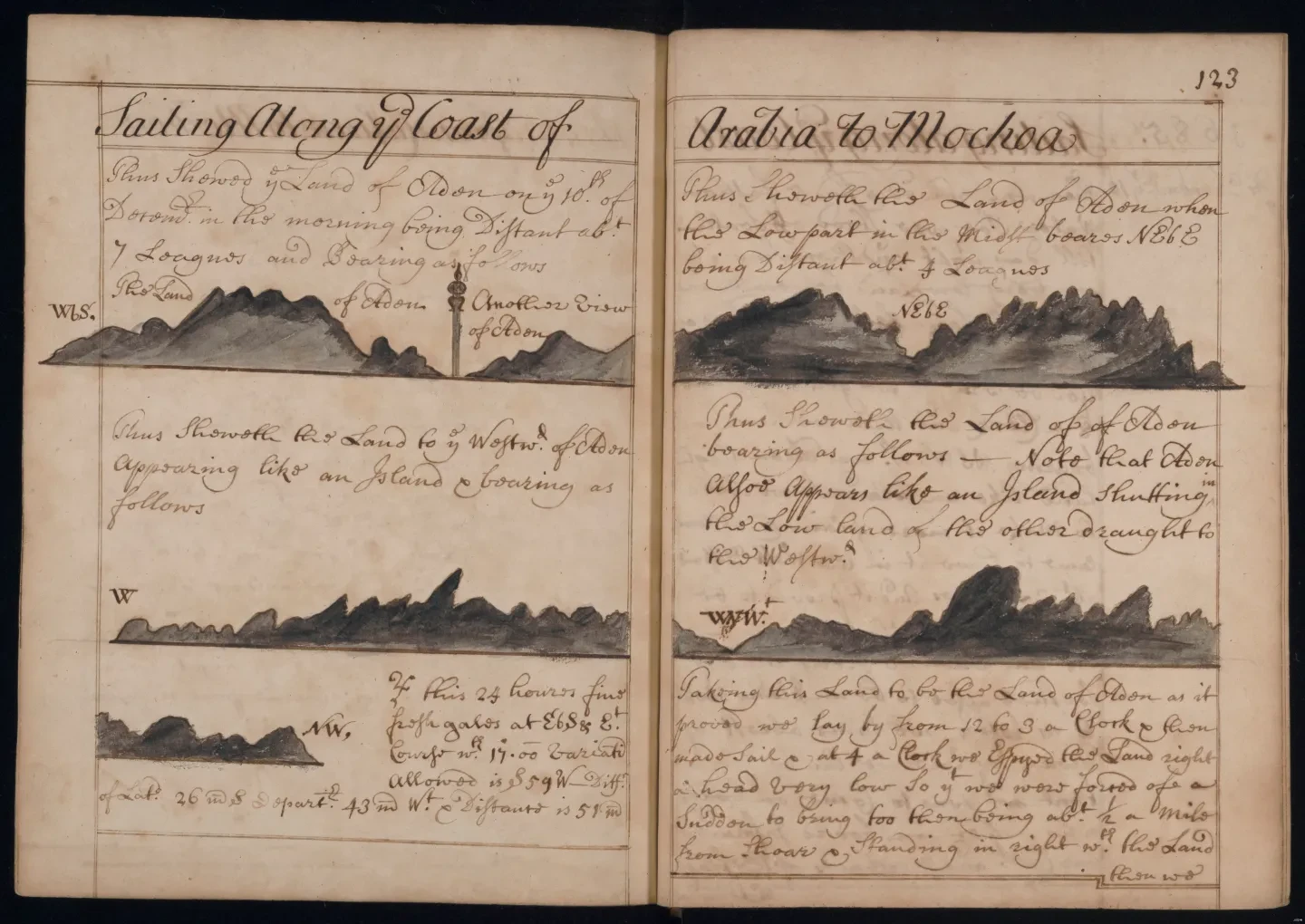

Most obvious to a first-time reader is the characteristic combination of text and image, where drawings are just not decorations but work alongside the writing to provide additional information and develop more complicated meanings. Mariners were often well-trained artists, not least because they were required to produce accurate coastal sketches to aid in navigation. These professional skills often infiltrated their journals, such as in this anonymous 1680s account of a voyage from London to the Persian Gulf (RMG ID: JOD/49), or the famous journal of Edward Barlow, where geographic studies are augmented by his keen eye for local wildlife (RMG ID: JOD/4).

The ink and paper skills they learned at sea also fed into their writing in other ways. Although these journals, written up neatly at a later date, are different from logbooks, the detailed technical records made during a maritime voyage, they were often imaginatively adapted from them: when nothing exciting was happening, Roch often fell back on the logbook’s familiar rhythm of date, position and weather.

There were also more exciting textual cultures on board an early modern ship that might make their way into journals. The mariners who were driven to write about their experiences were often also aspiring poets who passed their compositions around their ships, often in hope of impressing a superior, and later added their poems to their journals, just as verse often ornamented the printed books they encountered on land. They nonetheless made a motely school of versifiers.

The boatswain’s mate John Baltharpe handed an acrostic to ‘Captain Hunt’ asking for a new coat on a bitter, blustery day (‘Contrary Winds and Weather bad, | A watch Coat’s good, being thinly clad’) while the ship’s chaplain Henry Teonge scribbled mock-heroic satires and love songs, circulating them on loose papers among his shipboard community before slipping these sheets into his journal (RMG ID: JOD/6).

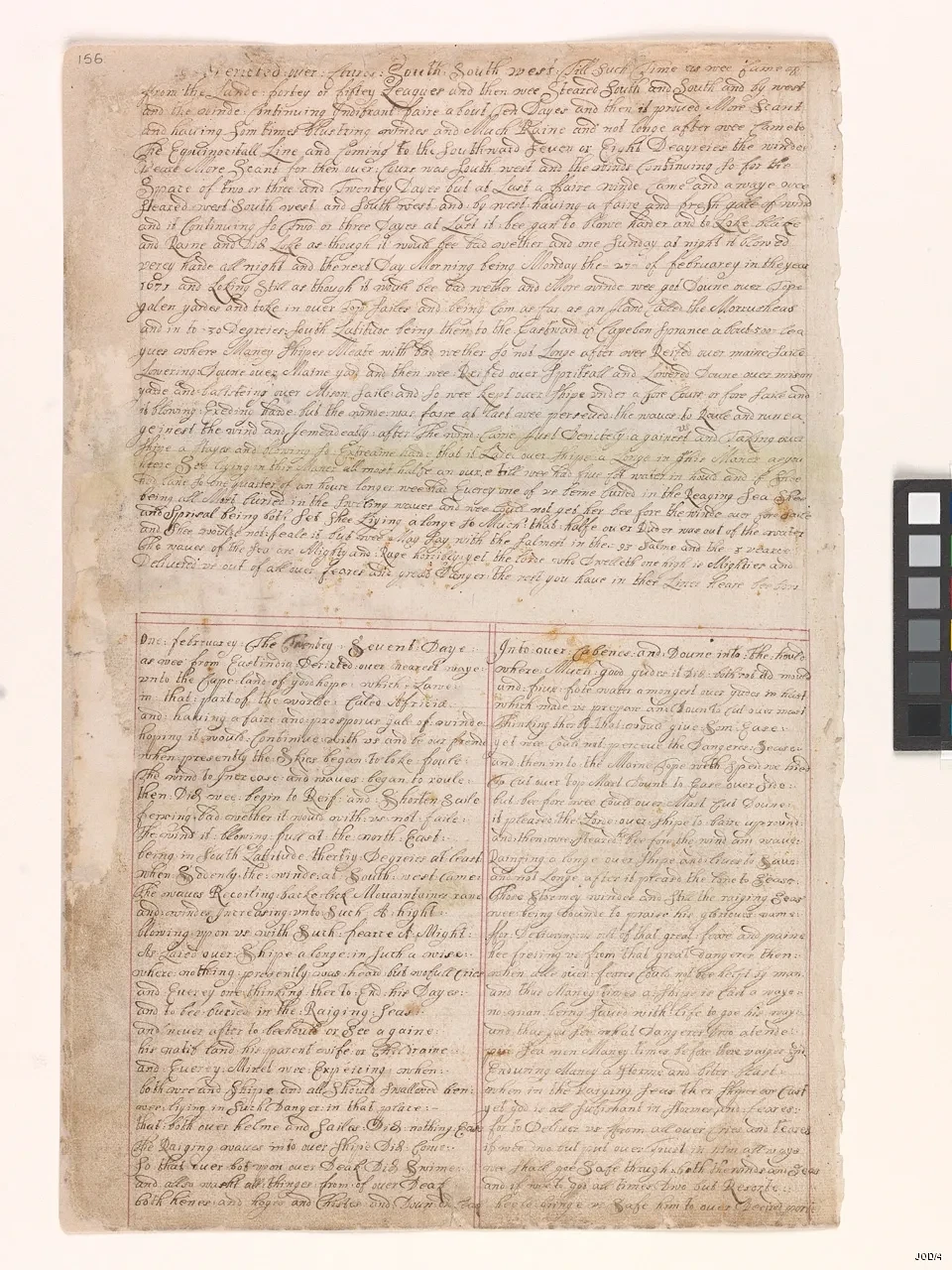

Barlow, on the other hand, copied the style of printed broadsides, neatly ruling out two columns for a poem to commemorate the survival of his ship The Experiment during a storm off the Cape of Good Hope in 1671:

The waves recoiling back like mountains ran,

And winds increasing unto such a height,

Blowing upon us with such fierce a might

As laid out ship along in such a wise

Where nothing presently was heard but woeful cries:

And everyone thinking there to end his days

And to be buried in the raging seas.

Hoping to escape such horrible fates, mariners were also particularly interested in astrology. This was not the sort of astrology we are familiar with today, focusing on star signs and the zodiac: instead, astrologers like Roch practised what was called ‘judicial astrology’, with his predictive models derived from astronomical observations.

By the end of the seventeenth-century this was a field that was going out of fashion as the new science championed by the Royal Society became more widespread, and a growing emphasis was put on the rational analysis of observable evidence. Astrologers were nonetheless keen to jump on this bandwagon, and to use the tools of the enlightenment to prove that their science deserved a place among its other emerging disciplines.

Among them were seafarers such as Francis Digby, whose professional skills at taking celestial measurements overlapped handily with the data-gathering required by practising astrologers: in his journal he correlated astrological and weather data, finding that ‘the Signes in which the Moone is have an extraordinary Influence upon the Weather’.

The sort of elaborate astrological projections found in Roch’s journal could be used to predict events in both the short and long term. The former included upcoming battles. Roch claimed that the other officers ‘fell alaughing’ when, on the eve of the two opposing fleets coming together, he predicted that there would be no battle, only for him to be proven right when a storm drove them apart: ‘I laughed at them, who knew not what to say but that I had raised the storm by magic art to make good my judgement: this was a Whimsey indeed!’

Astrological projections could also use someone’s birth date to predict a more general horoscope: one of Roch’s favourite books was Collectio Geniturarum (1662) by the famous astrologer John Gadbury, which brought together a whole host of celebrity nativities for his own evidence-based study. Gadbury’s book was the model for Roch’s own journal, albeit with his life replacing that of the Restoration celebrity.

In this, Roch experienced a stroke of tremendous good luck – or should that be providence? – because he found himself serving under one of Gadbury’s premier astrological celebrities, the dashing young courtier Captain Sir Frescheville Holles.

He even claimed that he had first recognized Holles from his description in Gadbury’s book (no such physical description exists: was Roch misremembering, or drawing on his own deductions?). Holles himself was well aware of Gadbury’s promise that ‘it is very remarkable, and worthy to be noted, than in the whole Figure, there is not one Planet in his Detriment’, and ‘Sir Frescheville Hollis his famous case’ was also talked about extensively by others. After Holles died in action in 1672 John Hoskyns reflected that ‘all england is full of’ the story of Gadbury’s failed prediction.

Unsurprisingly, Roch was starstruck. He recorded the impromptu couplets that Holles supposedly shouted during a storm, bragging that his destiny was too great to be broken by the weather:

Blow Windes beat Seas in vain you spend your breath

My Fate’s too great by you to suffer Death!

He similarly copied out the description of Holles published by the poet John Dryden in his poem Annus Mirabilis (1667), which celebrated the war at sea and how Holles persevered despite his left arm being shot off. Gadbury had explained how Mercury, ‘the natural Patron of Ingenuity’ combined with Mars to promise that Holles would be a warlike poet, and Dryden likewise described:

Young Holles on a Muse by Mars begot

Born Cæsar like to act & write great Deeds

Impatient to Revenge his fatal Shott

His Right hand doubly to his Left succeeds.

Copying out this poem alongside his own verse allowed Roch to put himself in the company of one of England’s greatest poets, an artistic equivalent to the wartime role described in his narrative, where he supported the great hero Holles at sea. By inserting this stanza into an explicitly astrologically-driven narrative Roch also cleverly used Dryden’s verses to support the validity of that science, drawing out the subtle astrological play concealed in these careful lines and transforming it into a firm endorsement of his beliefs.

Even after Holles’s death in 1672 he continued to shape how Roch imagined his own adventures, and his deft combinations of text and image. He recorded the story of one journey in 1677 when he, his dog and Robert Curtis, ‘a lad that had never bee on the salt water’, daringly sailed from Plymouth to London in a ‘little boat’, ‘a Voyage none e’er perform’d before | In such a Boat to Coast Albions Shore’. Roch commemorated this trip with a particularly striking illustration of the three of them gathered together in his boat.

However, I am convinced that in this self-portrait he was cleverly imitating Peter Lely’s portrait of Holles, now hanging in the Queen’s House, and which was widely available at the time in a printed reproduction (RMG ID: BHC2770). Here Roch, the figure on the left, is similarly one-armed and waving a swashbuckling sword, while to the right, on the other side of the canon, Robert Holmes is replaced by Curtis, his baton of command transformed into a wine glass.

Even this metamorphosis had precedent: looking back in Roch’s journal, we find him describing how, during preparations for the Four Days’ Battle, ‘Holles cals for wine & all our Company being aloft, drinks a Glasse to all fore & aft, which having all pledged round, every man repaired to his Quarter’. Journals like Roch’s are full of such hidden details, and in a deep and complex conversation with other holdings found across Royal Museums Greenwich.

In a concluding poem, he assured his readers that, no matter what they cared to think about astrology, he was proud of his contribution to knowledge:

Thus Dear bought Knowledge by Experience Gott,

Some Satisfaction doth afford to all.

That Love it; But to e’ry foolish Sott,

It appears nonsense, & nought worth at all.

Be’t how it will; It doth afford to me

Such Charms, as with Uranias Smiles agree.