In September 1665, the diarist and naval administrator Samuel Pepys visited his friend Henry Johnson, a shipbuilder.

Johnson had just completed a new wet dock at Blackwall Yard on the Thames’ north bank, built to accommodate the growing East India Company fleet. During construction the workers had found something remarkable sunk in the riverbank. As Pepys wrote:

'[...]in digging his late Docke, he did 12 foot under ground find perfect trees over-covered with earth. Nut trees, with the branches and the very nuts upon them; some of whose nuts he showed us. Their shells black with age, and their kernell, upon opening, decayed, but their shell perfectly hard as ever. And a yew tree he showed us (upon which, he says, the very ivy was taken up whole about it)[...]’

Samuel Pepys, ‘The Diary of Samuel Pepys’ (22 September 1665)

Pepys’s fascination with this submerged forest is just one example of how discoveries made on the banks of the Thames have given us a heady glimpse into the distant past. Today the river is barriered and embanked, yet its deeper human and natural histories still manage to seep through.

As the planet heats up, and London, Essex and Kent prepare for an uncertain riverside future, what can these stories tell us about the River Thames and the people who live alongside it?

Trees in the Thames - a sign of Noah's flood?

In Pepys’s time, as now, urban development and discovery went hand in hand. Over the decades and centuries that followed, more subterranean puzzles were unearthed.

When Brunswick Dock was built nearby in the late eighteenth century, hazel trees were found buried 12 feet beneath the surface of the riverbank. Their discovery caused a sensation.

A contemporary tourist guide described the scene:

‘Toward the end of the year 1789, and in all 1790, people came from far and near to collect the nuts, and pieces of trees, which were found, in digging this dock, in a sound and perfect state, though they must have laid there for ages. They seem to have been overset by some convulsion, or violent impulse, from the northward, as their tops lay toward the south’.

‘Blackwall’, The Ambulator; or, Pocket Companion in a Tour round London, Tenth Edition (London, 1807), 56.

Ghost forests were also found downstream in the early 1700s in Purfleet, Essex, on the Thames’ northern shore. In this case, it was not London’s expanding port that opened up the past. A recent storm had ripped a great flood channel through the riverside marsh, exposing ‘vast multitudes’ of ‘Subterraneous Trees’, when the tide receded.

Locals puzzled over the species of these blackened stumps. Some thought they were mostly yew trees. Other learned observers considered this unlikely so close to ‘brackish Waters’ and they were probably alder. One seemed to be an oak tree, still partly intact.

What were these trees doing so close to the water’s edge and so deep underground? Surely only the great biblical flood could explain such a topsy-turvy world beneath the Earth?

The Reverend William Derham, a priest and naturalist, reported at the time on this strange phenomenon to the Royal Society, addressing speculations that these trees had lain here ‘ever since Noah’s Flood’.

Though ‘the Spoils of that Deluge’ undoubtedly still existed he declared, the naturalist in Derham was as strong as the priest. The trees were probably ‘the Ruins of some later Age,’ he concluded, ‘occasioned by some extraordinary inundations of the River of Thames’.

'Most lov'd of all the Oceans sonnes'

Signs of early human life and some surprising non-human animals were also surfacing at this time.

Shortly after the Great Fire of 1666, an apothecary and antiquary John Conyers was digging near the River Fleet, a Thames tributary which flowed southwards through Gray’s Inn. Here in the gravel Conyers found a flint axe and what looked like the remains of an elephant. Again, some turned to the ‘Universal Deluge’ to explain such marvels. When in 1715 antiquary John Bagford published a report on these finds however, he considered the remains more likely to have belonged to the rumoured army of elephants brought over by the Roman Emperor Claudius in 43 CE. The axe, meanwhile, appeared to be a 'Weapon very common amongst the Ancient Britains'.

Bagford wasn’t to know how ‘ancient’ it was: this flint tool, now in the collection of the British Museum, is thought to date back 350,000 years.

At the same time that this enigmatic past of the Thames riverside was being revealed, the early modern centuries also saw the River Thames itself morphing into the toned, muscle-bound form of ‘Father Thames’.

The ships of the East India Company, Royal African Company, Hudson’s Bay Company and other trading ventures set out from London’s port in pursuit of spices, gold, furs, people to enslave and new territories to colonise. As they did so, poets and artists, navigators and statesmen reinvented the Thames, which now became a global player. Equally distant from both the pages of the Bible and the riverbed through which it flowed, the Thames was inserted into the more picturesque frame of classical myth and new ‘discoveries’.

Already in the Elizabethan age, Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1590s) saw the world’s rivers paying their respects at the marriage of the Thames, ‘the louely Bridegroome’, to the Medway River, his bride. Alongside the humble Thames tributaries were the ‘fertile Nile’, ‘Deepe Indus’ and other rivers of antiquity, as well as the Amazon and ‘Rich Oranochy, though but knowen late’ of the Americas.

For the poet John Denham half a century later in ‘On Cooper’s Hill’, the Thames was ‘the most lov'd of all the Oceans sonnes’.

In James Barry’s late eighteenth-century image of Commerce, or the Triumph of the Thames, this English stream was a semi-recumbent river god, borne victoriously across the waves by famous navigators and sea nymphs. The four known continents of Asia, Africa, Europe and America offered up their bounty to the god.

While the Thames embarked on a symbolic journey of imperial conquest, the river itself continued its parallel natural life, subject to tides and winds, flood and drought.

Discoveries from the mysterious past continued but were ever less likely to be seen as relics of a biblical event. The strange mutations of the Thames and its inhabitants became increasingly viewed through the lens of emerging science: geology, archaeology and palaeontology.

We now know that the shape of the Thames is tied to extreme long-term fluctuations in the climate, as well as tectonic activity.

Ten thousand years ago the Thames formed a confluence with the River Rhine in Doggerland, the land mass between the British Isles and mainland Europe, until melting glaciers after the last ice age slowly drowned the land to form the North Sea. Today, fishing trawlers and dredgers routinely pull up spearheads, hand axes, hyena bones and mammoth tusks from this lost ‘Thames-Rhine land’, along with the marine life scraped from the seabed.

Oscillations in the climate during these post-glacial changes are thought to be responsible for the ‘Purfleet submerged forest’ which William Derham documented. It is now dated to around 6,000 years old.

As sea levels rose and fell, successive ‘transgressions’ and ‘regressions’ of the Thames created very different riverside worlds over time.

In Trafalgar Square in the 1920s, builders digging the foundations of a new insurance headquarters found in the sand and gravel, 30 feet deep, the remains of hippopotami and European pond terrapins. These lived and died in the warm and much wider Thames river of the balmy ‘Ipswichian’ age, around 120,000 years ago.

Holding back the tide

The distant past of the River Thames and its inhabitants still offers up surprises.

One rainy day in 2013 on the eroding Norfolk coast at Happisburgh, a set of preserved footprints was discovered belonging to a group of adult humans and children. Dating back perhaps as far as 900,000 years, these are the oldest preserved human footprints outside of Africa. This ancient beach has also been revealed as the site of a proto-Thames estuary, from a time when the river flowed north eastwards into the sea through East Anglia.

These earliest known Thames-side people, with their famous feet, were not modern humans (Homo sapiens did not arrive in Britain until probably somewhere around 40,000 years ago). They were probably the much earlier Homo antecessor (‘pioneer man’), discovered along with the remains of ancient frogs, voles and now extinct species such as the giant beaver.

The River Thames itself was edged gradually to its current position by the ‘Anglian’ ice sheet that crept southwards and stopped around 450,000 years ago, as if out of courtesy, on the outskirts of today’s north and east London.

Today, the wandering Thames is encased in river walls for much of its length. Most famous are the Victorian granite embankments built to house Joseph Bazalgette’s sewage system.

But as this 1790s Robert Dodd painting of ‘Greenwich from the Isle of Dogs’ shows, everyday life along the tideway has long called for ingenious river defences.

Today the tidal Thames is protected by flood defences completed in the 1980s in the wake of deadly East Coast floods in 1928 and 1953. The iconic Thames Barrier at Woolwich keeps the shipping channel open, with its retractable hoods closing against high tides and flooding from rainfall.

But the barrier has been closing with increasing frequency in recent decades. As temperatures rise and ice caps melt, how to protect London and other riverside communities from the rising tides is hotly debated.

Global warming linked to human activity is thought likely to raise sea levels globally by anything from 3-8 mm annually to over five times that rate by 2100, according to a recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The Thames Estuary 2100 project is tasked by the Government with future-proofing the riverside in conditions of uncertainty. They are assessing schemes for cumulatively rising defences and new riverside flood storage zones. A new Thames Barrier is anticipated for 2070. One day, it may be necessary to try to exclude the tide altogether from London. A fixed barrage might span the river, with a lock system letting vessels pass up and downstream.

The long term future of the Thames is to some extent as unknown to us as its past was to the people of Samuel Pepys’s day, though the depth of scientific data now available would probably be as marvellous to them as the submerged forests beneath the riverbanks.

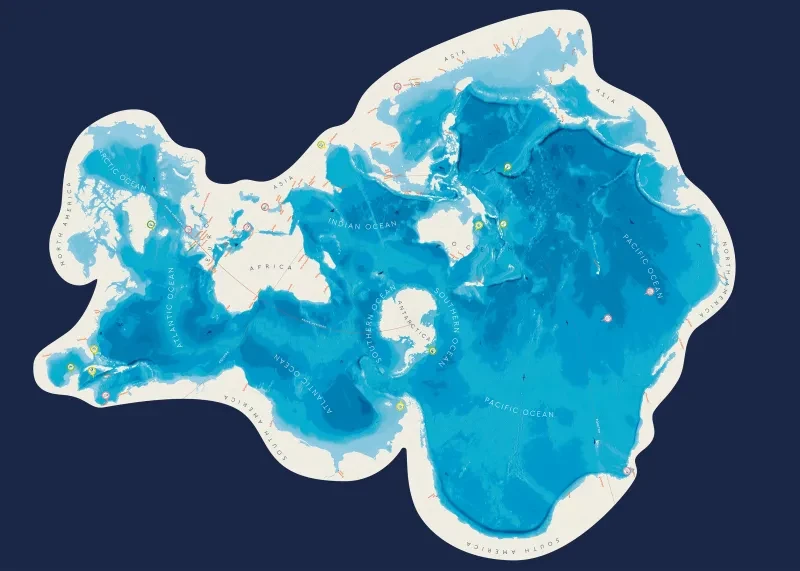

The new Ocean Map (pictured above), with its expanse of blues across the floor of the National Maritime Museum, vividly represents the world’s seas as a giant single ocean. Covering 71 per cent of the globe, this ocean bleeds in and out of our coastal rivers twice a day creating powerful and fluctuating streams. For the people of the Thames and other estuary communities, we need to prepare for what happens next in this blue world.

About the author

Vanessa Taylor is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Greenwich. Her book Seven Rivers: A Journey through the Currents of Human History (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) is available now. Alongside the Thames, this explores the worlds of the Danube, Ganges, Mississippi, Niger, Nile and Yangtze rivers. Her earlier work on rivers includes The London Journal, Special Issue: 'London's River? The Thames as a Contested Environmental Space', V. Taylor and S. Palmer (Guest Editors), 40:3 (2015).