One tent. Two people. 1,000 miles from the nearest base. When it comes to polar science, deep-field research is one of the most challenging environments in which to work.

‘It’s only when you take off at the end of the trip that you realise how vulnerable you were,’ says Dr Joanne Johnson, a glacial geologist working with British Antarctic Survey.

‘When you look down at this vast ice sheet, and the place you’ve been living for the past eight weeks - that’s when you realise how small you are,’ Johnson says.

Film by Steve Roberts and Al Doherty, captured during the 'ANiSEED' project in 2015

But while the scale of the operation can be overwhelming, the daily requirements for living and working in the Antarctic are often surprisingly mundane.

‘It’s definitely not as heroic as it looks,’ says Johnson. ‘I mean, I’m not special: moderate fitness, middle-aged. There are a lot of what you might call boring, housekeeping jobs – but they’re essential for survival.’

From pitching tents to keeping clean, cooking and communication, Joanne Johnson explains what it’s really like to live and work in an Antarctic field camp.

How to pack for Antarctica

We are given a kit bag by British Antarctic Survey, which has all the clothing we require to keep warm and safe. You don’t need much of your own clothes: even items like thermal underwear are provided for.

You’ll probably be disgusted to know I’ll probably only have about three pairs of thermals for the whole eight weeks! I might have a few more pairs of knickers, but even then I'd wear them more than once. We can wash things by hand, but it’s laborious.

When it comes to packing, I tend to focus on those days where I’ll be stuck inside the tent due to bad weather: what will keep me occupied?

My answer? Knitting. It’s easy to pack, lightweight, and keeps me busy for a long time. I knit things like scarves for people back home, anything that I can pick up and put down quickly.

I also take books, and always pack The Three Musketeers. Somehow it’s become associated with my research trips; it transports me away from everything.

Pitching the tents

Before flying to our location, we’ll assess the terrain using satellite imagery and select a potential campsite. We're looking for a big, broad, snowy area free of crevasses to land the plane.

Once landed, pitching the tent is our first job. It has to be up before the plane leaves to make sure we’re safe and have shelter.

The tents are 2x2m pyramid tents that you share with one other person. They’re quite easy to pitch: you dig four holes for the poles, and then it all erects in one piece. We carry lots of boxes with all our equipment and supplies, so we’ll put these round the outside of the tent to stop it blowing away.

Then one of us will go inside and start laying things out. Cooking boxes, pots and pans are laid out down the middle. The radio is at one end, and then each person has a side to make their own.

The toilet is in a separate tent. It’s essentially a bucket dug into the snow with a wooden seat over the pit. It’s not the warmest experience first thing in the morning, but at least it’s private.

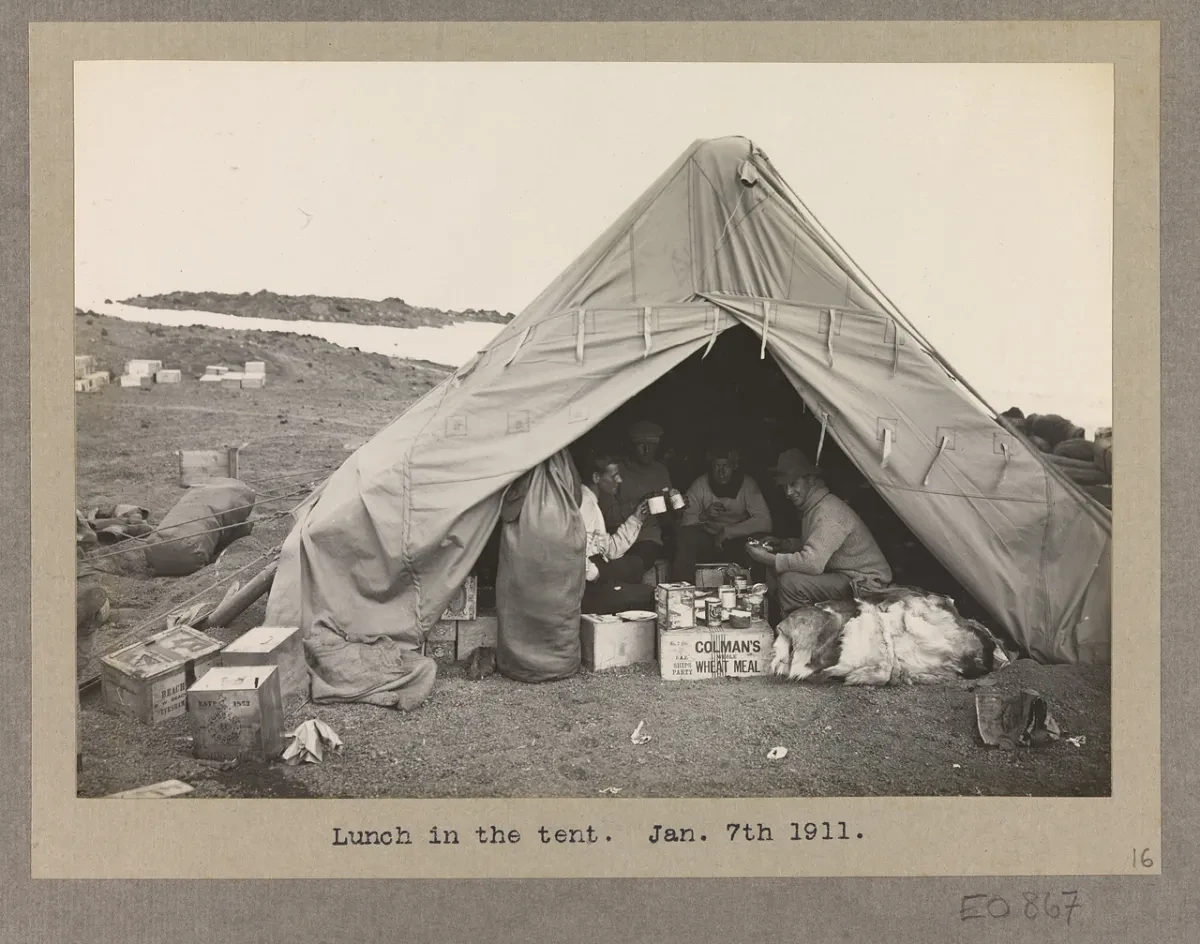

Tents and tea breaks

This photograph was taken during Captain Robert Falcon Scott's British Antarctic Expedition in 1911. It shows four expedition members having lunch in a canvas tent during the unloading of the ship Terra Nova. Just like Johnson's description of the inside of her tent, here ration boxes and rations run down the centre of the tent, acting as a makeshift table.

Sleeping in Antarctica

Camping in Antarctica is not as uncomfortable as you might imagine.

The base of your bed is a wooden board, laid on top of the groundsheet. On top of that will be a carry mat, followed by a thick airbed.

The comes our little piece of luxury: a sheepskin rug! It’s not the most lightweight way to travel, but it is comfortable. Finally we’ll have our sleeping bags, which when rolled away double up as bolsters to sit up on.

Sealskin for all seasons

This early polar sleeping bag is made of sealskin, and was used by Surgeon Commander George Murray Levick on the British Antarctic Expedition 1910-14.

Polar rations and Antarctic treats

The one constant of our days in camp is melting snow. Whatever we’re doing - cooking, cleaning, washing, drinking - we always need water.

That means the stove is always in use. We use Primus stoves, the type which have been around for decades. They may seem old-fashioned, but the advantage is that all the parts can be replaced easily. Without your stove you’re basically dead; we carry spares of everything.

We’re provided with daily ration boxes, which provide everything you need for a recommended intake of 3,500 calories.

It’s quite boring food: mostly dehydrated stuff in a packet that you add water to, plus biscuits and chocolate. If you want any extra goodies or proper things to cook, you have to take it with you from the research station.

Sometimes people are really into cooking, and to break up the week we might arrange a ‘curry night’, bake some bread, or even make a little afternoon tea. It's amazing what you can do with just a Primus stove!

Peckish for pemmican?

This is a tin of 'pemmican', part of the rations supplied to the British Arctic Expedition of 1875 led by George Nares. Pemmican is a block of dried and pounded meat mixed with fat.

Keeping clean

I wash a bit more now than I did when I first went to Antarctica. Every week I’ll take a couple of flasks of hot water, an empty plastic biscuit box and a flannel into the toilet tent and have a complete strip wash. It can be quite chilly, but it always feels good afterwards.

I’ve never washed my hair in the field. It’s not lovely, but after about three weeks I find it tends not to feel any dirtier!

It’s only when you’re on the plane back to the research station and in the warm cabin that you begin to notice the smell…

Communication in the Antarctic

We have a scheduled radio call with the research station every day. We check in to let them know we’re safe, and they’ll share the latest weather report.

Communications back home have changed so much since I first went to Antarctica in 2002. During my last expedition, we had a satellite phone that allowed us to ring home basically whenever we wanted. The device we used, an Iridium GO!, also gave us email access.

Personally I don't feel it's necessary to phone home, and sometimes it can be a bit of a distraction. It's also difficult for the people back home, as it brings into focus the fact that you're not there.

I've got two children; for them it’s not always the most helpful thing. My husband and I kind of agreed that we wouldn't contact each other that much except by email. I know other people however who phone home every day.

Spread the word

This balloon was used during the search for members of the Arctic expedition led by British explorer Sir John Franklin. Rescue ships released hydrogen-filled balloons like these, carrying bundles of messages attached to burning fuses. As the fuses burned through the messages were let loose. The idea was that these rescue notes could be scattered over as wide an area as possible.

Field guides and campmates

Most of what I do involves working on my own with just a field guide for company.

The field guide’s remit is to look after the scientist. They assume that the scientist is basically incapable of looking after themselves – sometimes this is true! Because we’re so focused on the science, we can forget things. In the past both scientists and field guides were normally male, but that’s not always the case now.

I’m a people person. To me it doesn't really matter who they are, I'm just interested in what makes them tick. And that helps: you’ve got six to eight weeks together, so you need things to talk about. Often I'm with somebody who I would never come across in normal life; it's fascinating getting to know them.

Some people are quieter of course, but that’s OK: you just have to measure them up at the beginning. People do need their own space, especially when you're with them all the time.

Keeping safe in Antarctica

The feeling of vulnerability does stay with you. You’re kind of aware of it in the back of your mind, knowing that if you have an accident it’s potentially very serious.

The last place I was in was 1,000 miles from the nearest research station - about as far away from contact as you could be.

You have to really trust the person you’re with, but you also need to rely on the whole system: everybody working at the station on your behalf, the people who check the weather, who listen to the radio reports.

The way that British Antarctic Survey works is so professional and efficient. You’re at one end of it, but there’s a whole system working for you. You know you’re in good hands.

Main photo © Iain Rudkin

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.