What is a sea shanty?

Sea shanties are traditional songs originally created and sung by sailors at sea.

Singing has been a part of life at sea for centuries. But sea shanties traditionally take a very particular form:

- They are generally 'call and response' songs, with one singer (known as a 'shantyman') leading and everyone else replying with the chorus.

- They have a regular, heavy rhythm. There may be dozens of versions and verses, but the tune and tempo remain constant.

What's the difference between sea shanties and other sailor songs?

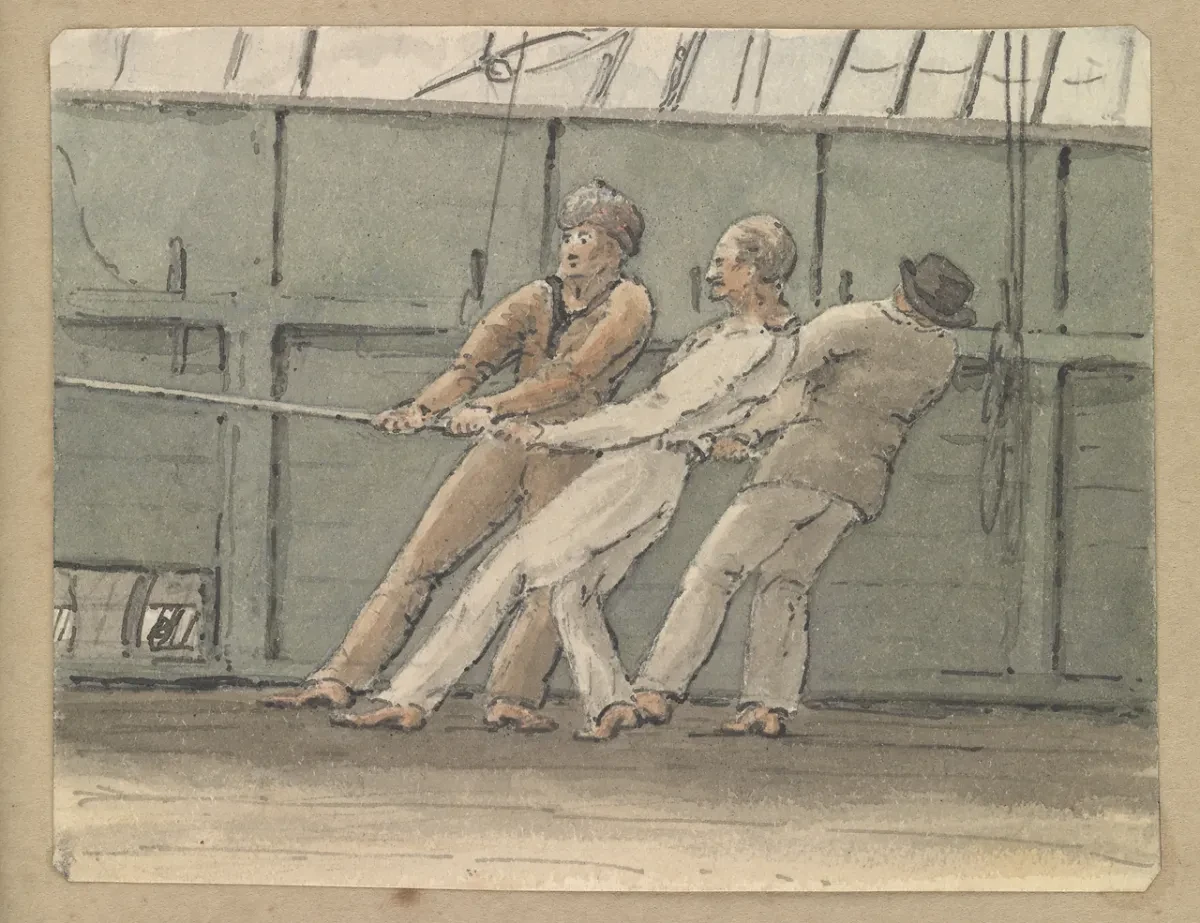

Sea shanties were work songs, devised to accompany particular actions or tasks on board ship.

They could help keep time among groups of sailors, coordinate physical movements like hauling ropes and raising sails, and relieve the boredom of long, repetitive tasks.

How the Sea Shanty originated is not difficult to discover. It has undoubtedly grown out of the natural inclination one feels in hauling, or in otherwise performing any rhythmical operation, to keep time with one's voice, feet or hands, in parallel rhythmical sound.

William Saunders, ‘Sailor Songs and Songs of the Sea’, 1928

Why are they called sea shanties?

The term 'sea shanty' itself first emerged in the 1800s. One often proposed origin is that it came from the French word 'chanter', meaning to sing.

Others have linked it to the English word 'chant', or even made connections with other work songs: North American lumberman songs for instance often began with the line, 'Come all ye brave shanty-boys'.

What is the history of sea shanties?

Historians have traced examples of what might be called sea shanties back to at least the 16th century. However, the songs as we know them really flourished during the 19th century on board large sailing ships.

"A lot of people assume that these songs was naval, but it was predominantly merchant ships where these songs were sung," says historian Kate Jamieson. "That’s why you have so many songs about whaling for instance."

Square-rigged vessels like Cutty Sark required groups of men to coordinate in hauling ropes and setting the sails. Ships' equipment such as the capstan - a type of winch often used to raise anchor - also needed multiple people winding together for long periods.

That explains the rise of the sea shanty: they helped make these hard group tasks easier - or at least more bearable.

The purpose of a hauling shanty was rhythm to the task of extracting just that last ounce from men habitually weary, overworked and underfed.

Harold Whates, 'The Background of Sea Shanties'

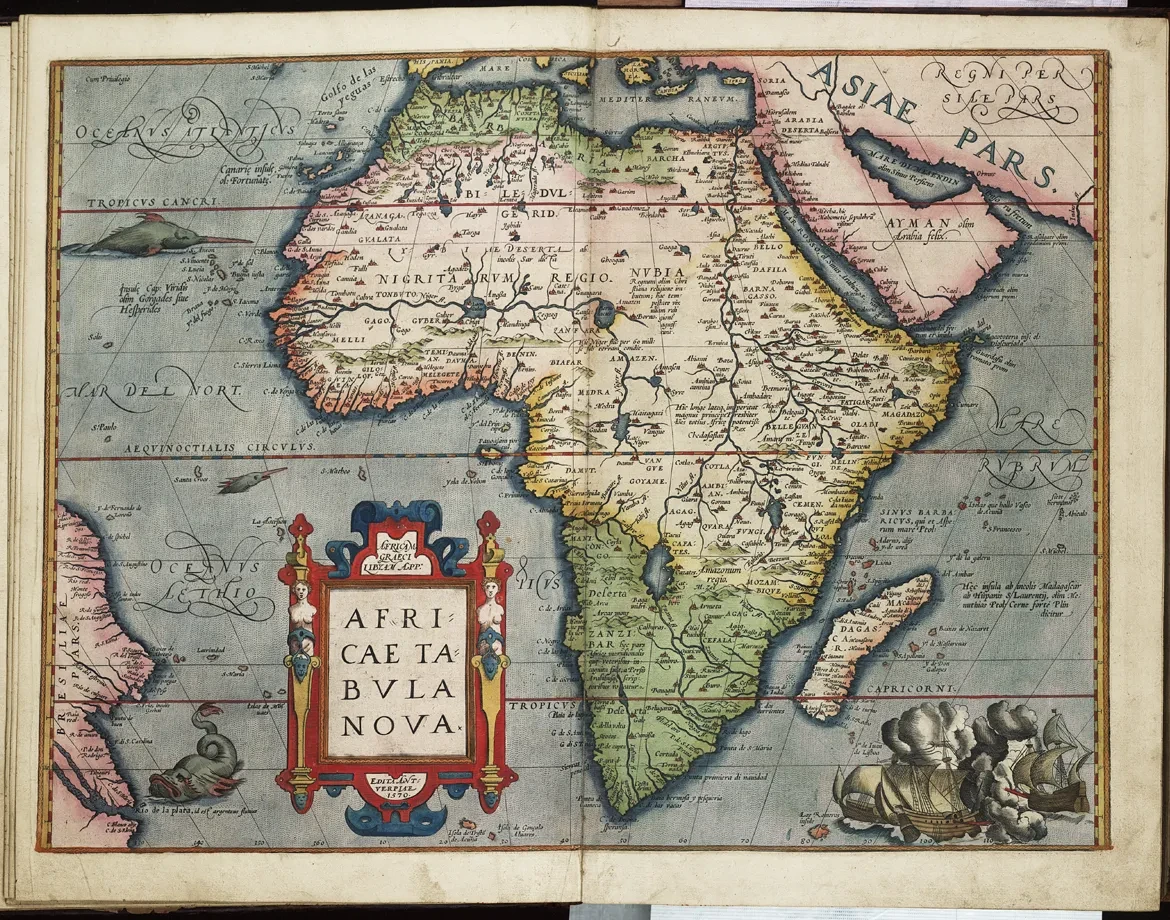

How does this relate to African culture and music?

'Call and response' is one form of music that has roots in the continent of Africa. Here, one person sings a line of a song, and this is repeated by the rest of the group.

Music, like people, has always travelled whether through a family, community, country, even crossing the world. When people travel, they take their music with them. This is especially true for people who travel for their jobs like sailors and people with things to sell.

British ships often had multi-ethnic crews as sailors were recruited from across the world, and black sailors have served on British ships for over 450 years. There were many cultural and musical influences on the development of shanties, as different groups of sailors sang songs together to get through the work day.

You can find out more about black sailors and sea shanties via the educational resources produced by the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

British, American and Australasian sailors all had their own versions, but it wasn't just English-speaking crews who sang while at work. French and Breton sailors for instance have their own shanty traditions, including songs such as Le Capitaine de San Malo.

As steam ships began to replace sailing ships in the latter half of the 19th century however, the type of work on board ship changed - and so did the musical accompaniment.

What types of sea shanty are there?

Each type of shanty was traditionally linked to the job at hand.

'Short drag' shanties were designed for short, hard bouts of pulling. A song like 'Haul on the Bowline' is a good example of this: every time the crew shouted 'haul' during the chorus they could give the rope another hard tug:

Haul on the bow'lin

The bow'lin haul

The well-known 'Drunken Sailor' is a different kind of short drag shanty, a 'hand over hand' shanty with two or more pulls per verse.

Long haul or 'halyard shanties' by contrast are songs for more sustained periods of pulling. Shanties like 'Blow the Man Down' included multiple rambling verses: the crew could rest while the shantyman displayed his lyrical skill:

Come all ye young fellows that follow the sea,

Way-hay, blow the man down,

And pray pay attention and listen to me,

Oh give us some time to blow the man down.

Other types include capstan and pumping shanties, designed for periods of relatively easy but continuous effort.

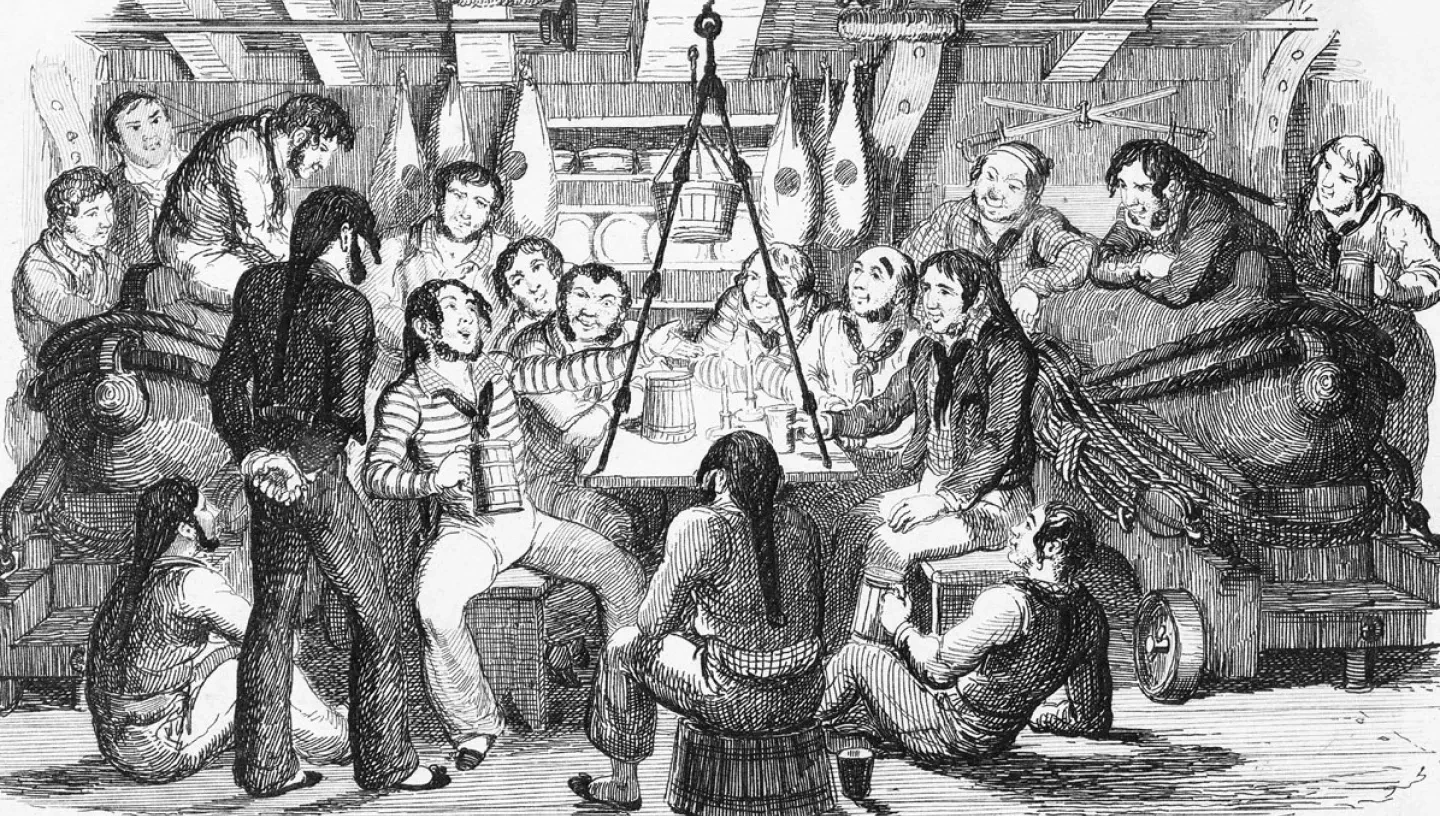

"The more you listen to them, the more you pick out the timings and the calls and responses," says Jamieon. "Listen to the one about Napoleon, 'Boney'. It begins with, 'Boney was a warrior,' and then everyone yells back, 'Way, hey, ya!' It keeps you in time when you're pulling lines, but it also keeps you motivated."

"The more lyrical ones are different," she adds, "perhaps used when sailors were relaxing in the evenings. There’s a lovely one called ‘Leave her Johnny’, which is more of a song than a work song."

The differences can be hard to pick out today, but it seems that a well-chosen song could make a "great difference" to the job at hand.

The sailor's songs for capstans and falls are of a peculiar kind, having a chorus at the end of each line. The burden is usually sung, by one alone, and, at the chorus, all hands join in —and the louder the noise, the better. With us, the chorus seemed almost to raise the decks of the ship, and might be heard at a great distance, ashore.

A song is as necessary to sailors as the drum and fife to a soldier. They can't pull in time, or pull with a will, without it. Many a time, when a thing goes heavy, with one fellow yo-ho-ing, a lively song, like "Heave, to the girls!" "Nancy oh!" "Jack Cross-tree," etc, has put life and strength into every arm.

We often found a great difference in the effect of the different songs in driving in the hides. Two or three songs would be tried, one after the other; with no effect;—not an inch could be got upon the tackles—when a new song, struck up, seemed to hit the humour of the moment, and drove the tackles "two blocks" at once. "Heave round hearty!" "Captain gone ashore!" and the like, might do for common pulls, but in an emergency, when we wanted a heavy, "raise-the-dead" pull, which should start the beams of the ship, there was nothing like "Time for us to go!" "Round the corner," or "Hurrah! hurrah! my hearty bullies!"

Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana Jr

Why are people singing sea shanties on TikTok?

In December 2020 Scottish singer Nathan Evans uploaded a video of himself singing a song called 'The Scotsman'. Another of his performances, 'The Wellerman', quickly gained momentum, with other users inspired to add their own duets, harmonies and responses.

#ShantyTok was born.

From violin accompaniments to electro remixes, TikTok has given new life to these hard-working, long-lasting songs of the sea.

"Different people are perhaps becoming more aware of these songs thanks to TikTok, but shanty bands have been popular for years. In Falmouth there's even an annual sea shanty festival," says Jamieson.

Why have they caught the imagination? "They’re simple, the choruses are relatively short, they’re not difficult to learn, they have a nice rhythm – all qualities which made them good to work to in the first place!" Jamieson suggests.

"Some years ago the game Assassin's Creed: Black Flag led to an interest in shanties, and now we're seeing them rise again. I think it's worth everyone discovering the background to these songs."

What does 'The Wellerman' song actually mean?

Claire Warrior, senior exhibitions curator at Royal Museums Greenwich, explains the history of TikTok's viral sea shanty:

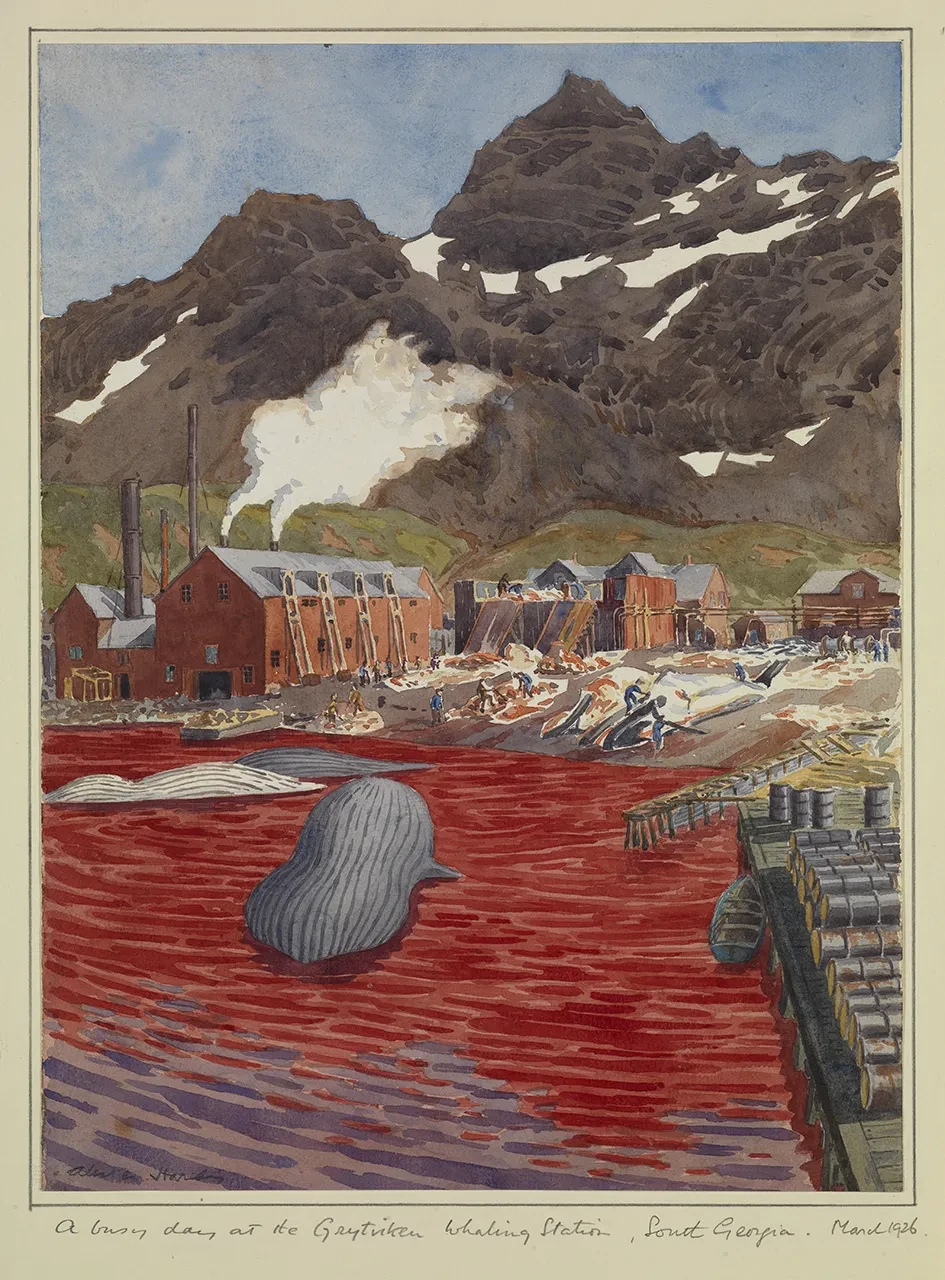

‘The Wellerman’ is a New Zealand folk song, which refers to 19th century right whale hunting.

Whales were big business at this time: the streets of London were illuminated by burning whale oil, and whale oil and baleen (the bristly plates some whales use to filter their food) were used in products from corsets to umbrellas and soap. Right whales were so named because whalers thought they were the ‘right’ whales to hunt – slow moving, they swim close to the shore, yield large amounts of oil, meat and baleen, and float when they are killed.

The first shore-based whaling stations in Aotearoa New Zealand were established in the 1820s. 'Wellermen' were the ships owned by Weller Brothers of Sydney who supplied provisions to the whalers, including, yes, "sugar and tea and rum". There doesn’t seem to have been a ship called Billy of Tea, but a ‘billy’ was a metal can used for boiling water.

By 1839, some 200 ships were working in the waters around the country, but this industry (and it was an industry, such was the scale) led to a complete collapse in the whale population by the 1850s. At least 150,000 southern right whales were killed in the whaling trade, hunted nearly to extinction. Even today, they number only about 7,500.

Whaling was a brutal business. ‘Tonguing’ refers to the tonguers, men who would cut up the whales on shore; they also often acted as intepreters with Māori communities, who also worked as part of the whaling crews.

This vivid watercolour by Alister Hardy comes from further south, from the remote Grytviken whaling station in South Georgia. In the 1920s, Hardy was the zoologist for the ‘Discovery’ investigations, sent south to research whales, their food sources and the ocean itself, to ensure that they did not become extinct.

Cutty Sark has its very own resident sea shanty group. 'Swinging the Lead' make regular appearances on board, bringing the ship alive by singing traditional songs.

Discover more

Find more stories of the sea at the National Maritime Museum and Cutty Sark