For centuries, a life at sea was barred to women in Britain – as well as the adventure, danger and excitement of maritime voyages.

But not everyone submitted to these restrictions. There are numerous examples of young women who disguised themselves as men in order to go to sea.

Author Vivien Morgan has traced the stories of these boundary-breaking seafarers in her book Cross-dressed to Kill. Here she introduces just some of the women who went to sea disguised as men.

Female fighters

The highest number of cross-dressing women who became soldiers, sailors or marines is recorded in the 18th century.

As Jane Austen wrote, ‘If adventures won’t befall a young lady in her own village, she must seek them abroad’. This is what scores of teenage girls and twenty-somethings who yearned for adventure, were ‘tomboys’ by nature and enjoyed physical exercise, did.

During this century, wars between European countries were waged over a number of issues, including territory, succession to various thrones, and trade.

The British army was stretched thin across the world and in desperate need of recruits, especially due to three East Indies wars against France to protect the British East India Company.

The trading company was hugely important, accounting for half of the world’s trade, particularly in basic commodities including cotton, silk, indigo dye, salt, spices, tea and opium.

A number of young English women are known to have travelled to India and the Caribbean in order to fight in these Anglo-French trade wars. Slipping through the recruitment process, they embarked as sailors on Royal Naval ships from Portsmouth in the 18th century.

Hannah Snell

Hannah Snell (1723-1792) was one. She had no problem signing on as a volunteer as part of Admiral Boscawen's fleet, which was being fitted out for a tour of duty in the East Indies.

Hannah was on board the Swallow, a sloop-of-war, which set sail with other battleships, men-of-war or frigates and a convoy of fourteen hundred regular troops. Their objective was to provide naval protection for the English East India Company ships.

On the long voyage, Hannah became a favourite both among the men and officers because she ‘would very readily either wash or mend linen or stand cook, as occasion required’. She earned the nickname ‘Miss Molly Gray’ because of her youthful complexion and lack of a beard, although she had apparently shaved her head before enlisting as was the custom to avoid lice.

While Hannah was teased for her softer and ‘feminine’ nature, it was her courage and her ability to fight and kill ‘for she was also expected to stand on the quarter deck during battles and fight with small arms’ that she wrote, ‘procured the love and esteem of all her fellow-soldiers’.

Hannah was on the front line of the final assault on Pondicherry, when she was badly hit after having fired 37 rounds. 11 musket balls lodged in her legs and allegedly one in the groin. At the field hospital, she did not tell the surgeons of her groin wound, terrified that this would give away her secret. She was determined ‘to run all risks even at the hazard of her life, rather than her sex should be known’.

Although in the most terrible pain as the surgeons tended only her legs, Hannah apparently found a local Indian woman to bring her ointments and dressings, without letting on that she was a woman. Hannah ‘probed the wound with her finger till she came where the ball lay and then upon feeling it thrust in both her finger and thumb and pulled it out’. It healed miraculously along with the other wounds.

On another ship, the Eltham, she was almost revealed when receiving twelve lashes as a punishment for disobedience. The boatswain of the ship ‘taking notice of her breasts, seemed surprised and said were the most like a woman’s he ever saw; but as no person on board ever had the least suspicion of her sex, the matter was dropped without any farther notice being taken’. Hannah said she stood as upright as possible and ‘tied a large silk handkerchief around her neck, the ends whereof entirely covered her breasts'.

After 5 years away, she returned to Portsmouth. It was only when she met up with her shipmates to get their severance pay that Hannah admitted her true sex to her fellow sailors, revealing that the sailor they’d known as 'James Gray' had been a disguise.

Hannah’s published story The Female Marine was a bestseller. She ran a public house called ‘The Female Warrior’ in Wapping on the Thames for some years. The pub sign showed her in regimental dress on one side and in marine uniform on the other, with the inscription ‘The Widow in Masquerade’.

Mary Read

Mary Read (1685-1721) also enlisted as a sailor in disguise, and arrived in the West Indies where she subsequently became a pirate.

When Mary’s ship was captured by the notorious pirate Jack Rackham, she was forced to work for him. She fell for a handsome young sailor and confessed to him that she, Mary, was in fact a female – only to find that the young man was also a female in disguise, named Anne Bonny.

Theirs was not a happy ending, however, as the British Navy captured them. Rackham was hanged, and Mary died of a fever before she could be hanged. Anne escaped, her whereabouts unknown.

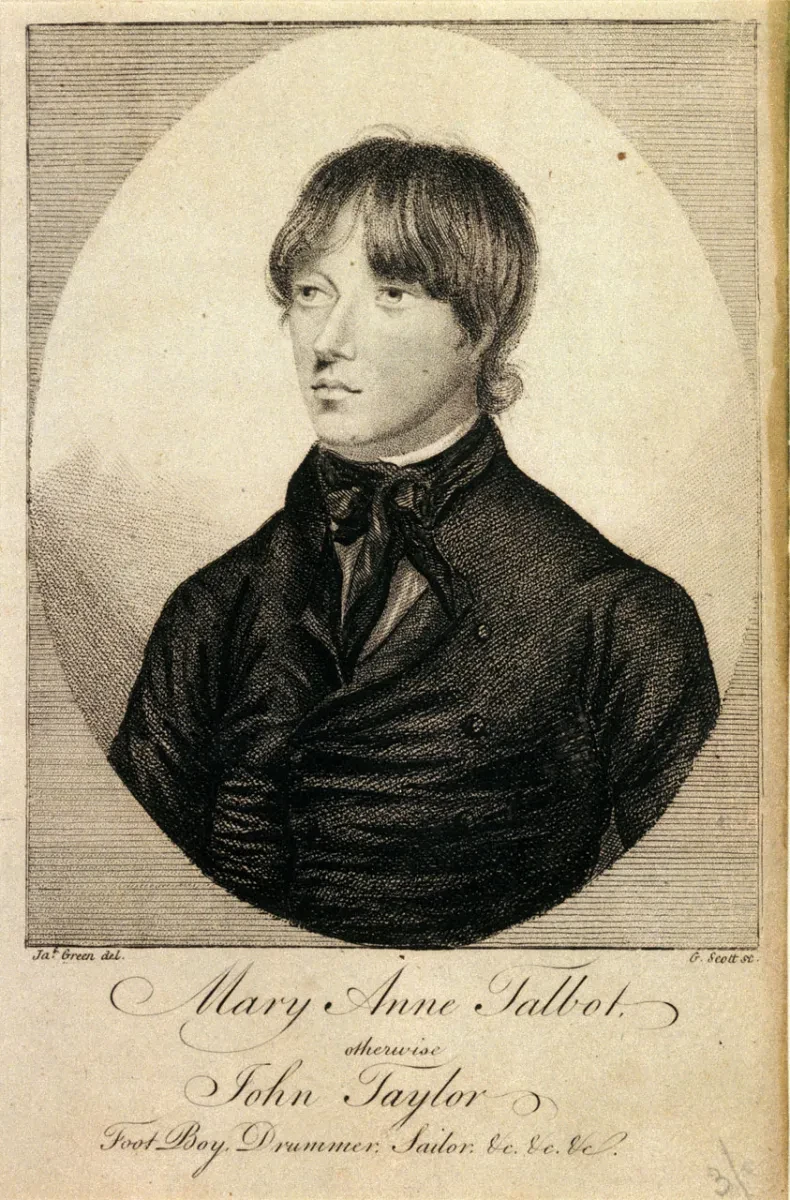

Mary Anne Talbot

Mary Anne Talbot (1778-1808) was the 15-year-old heiress and illegitimate daughter of the Earl of Talbot. She was forced to board a British naval ship bound for Haiti with her abductor, Captain Bowen. He had raped her and dressed her as a cabin boy.

She saw action in the Caribbean and back in Flanders on their fleet’s return to European waters. After Bowen’s death on the battlefield, Mary continued as a sailor, and later her ship was captured by a French boat.

Rescue came from the 100-gun Royal Navy ship Queen Charlotte, and Mary Anne was taken on board where she told her story – but not her true sex – to Admiral Lord Howe.

He believed her and offered to transfer her as a 'powder monkey' (someone who manned naval artillery guns as a member of a warship's crew) to the new and powerful 74-gun HMS Brunswick.

As Mary Anne reported when telling her story, Captain Harvey – on realising ‘that my manner was very different from that of many lads of board’ – promoted her to be ‘his principal cabin-boy’.

She took part in Lord Howe’s ‘Glorious 1st of June’ attack on the French fleet, designed to stop imports of grain from America. However, it was unsuccessful and the ship returned to England. Mary Anne died young at 31, after three years as a sailor in disguise.

William Brown

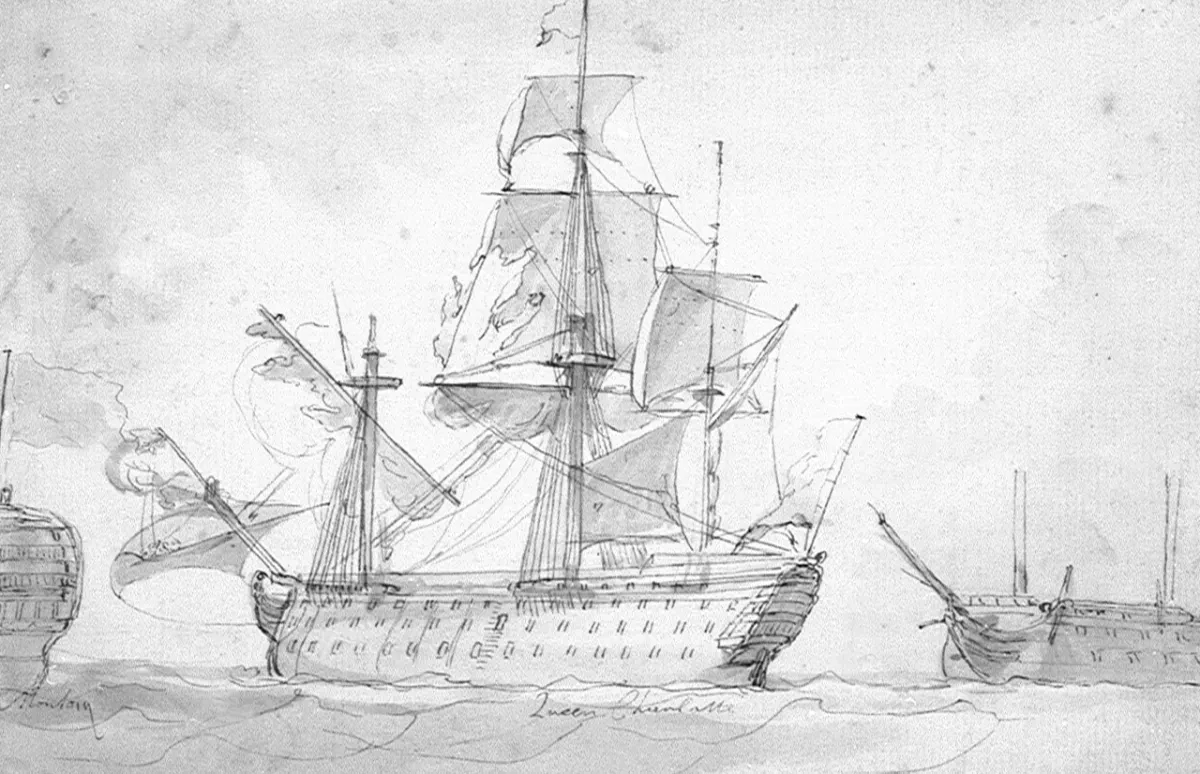

'William Brown' is the only known female black sailor who enlisted in the British Navy. The young woman who used this as her alias was reportedly from Grenada, and signed on in the early 19th century.

It is undisputed that she was a sailor of the battleship HMS Queen Charlotte (pictured) but her service record is unclear. There are no images of her.

Paul Daniels

'Paul' had the bad luck to be spotted by an eagle-eyed sergeant when he was exercising some soldiers on board a transport ship at Portsmouth in 1761.

He thought young Paul Daniels ‘had a more prominent chest than ordinary'. He sent for him to come to his cabin after the drill, and told him his suspicions. Daniels, to avoid a physical search, ‘confessed her sex’.

Arthur Douglas

Only five feet tall and aged about 19, 'Arthur' worked as a landsman on board the privateer ship the Resolution. Working his passage from London to Liverpool, he went aloft to furl the sails, ‘was frequently mustered among the Marines at the time they exercised’ the small firearms, and generally seemed to be of ‘very modest character, and by his behaviour to have had a genteel education'.

It wasn’t until the ship docked at Liverpool that the truth came out that Arthur was actually a teenage girl. One of the messmates on board discovered her sex and tried to sleep with her. She agreed ‘to prevent a discovery of her sex to the whole ship', but when they landed refused to keep her word, so the Captain was told.

Jane Meace

Jane tried to enlist as a Marine in 1762. In Uttoxeter, a young man ‘came to a recruiting party of Marines’ being held at an alehouse called The Plume and Feathers.

He enlisted as John Meace and asked for all his bounty money, but only got one shilling, as they thought he needed ‘cloathing and other necessaries'. However, the following morning her sex was discovered by ‘one of the men laying hold of her coat over the breast to see how it fitted'.

Hannah Witney

Hannah Witney's story dates from 20 October 1761. A young man who had been impressed (press-ganged) at Plymouth was sent to one Captain Toby. On arrival he was put in prison, but not liking it disclosed that he was in fact a young woman.

The naval report says that she was 'Born in Ireland, had been a Marine on board different ships for upwards five years’, and that she would not have ‘disclosed herself’ if she had been ‘allowed her liberty'. This was duly granted. A naval report included details of a young Lady ‘on board the Fleet in Man’s Apparel, who showed all the signs of most undaunted Valour'.

Several other women, the report continued, ‘are still living and some of them in this Town who have served whole campaigns and fought stroke by stroke by the most manly soldiers'.

They, like so many other valiant women who rallied to the patriotic call to defend their country, will remain unknown. But those now listed will have a place in the military and social history books.

Vivien Morgan is the author of Cross-dressed to Kill: Women Who Went to War Disguised as Men. You can buy a copy from retailers including Waterstones and Amazon.

Discover more remarkable women at sea