While Mars may be the planet that springs to mind when there are discussions of possible alien life in our Solar System, a publication on the discovery of a rare gas (phosphine) in Venus's atmosphere may mean that there is more than one planet that possesses the potential for life.

The search for life on Venus

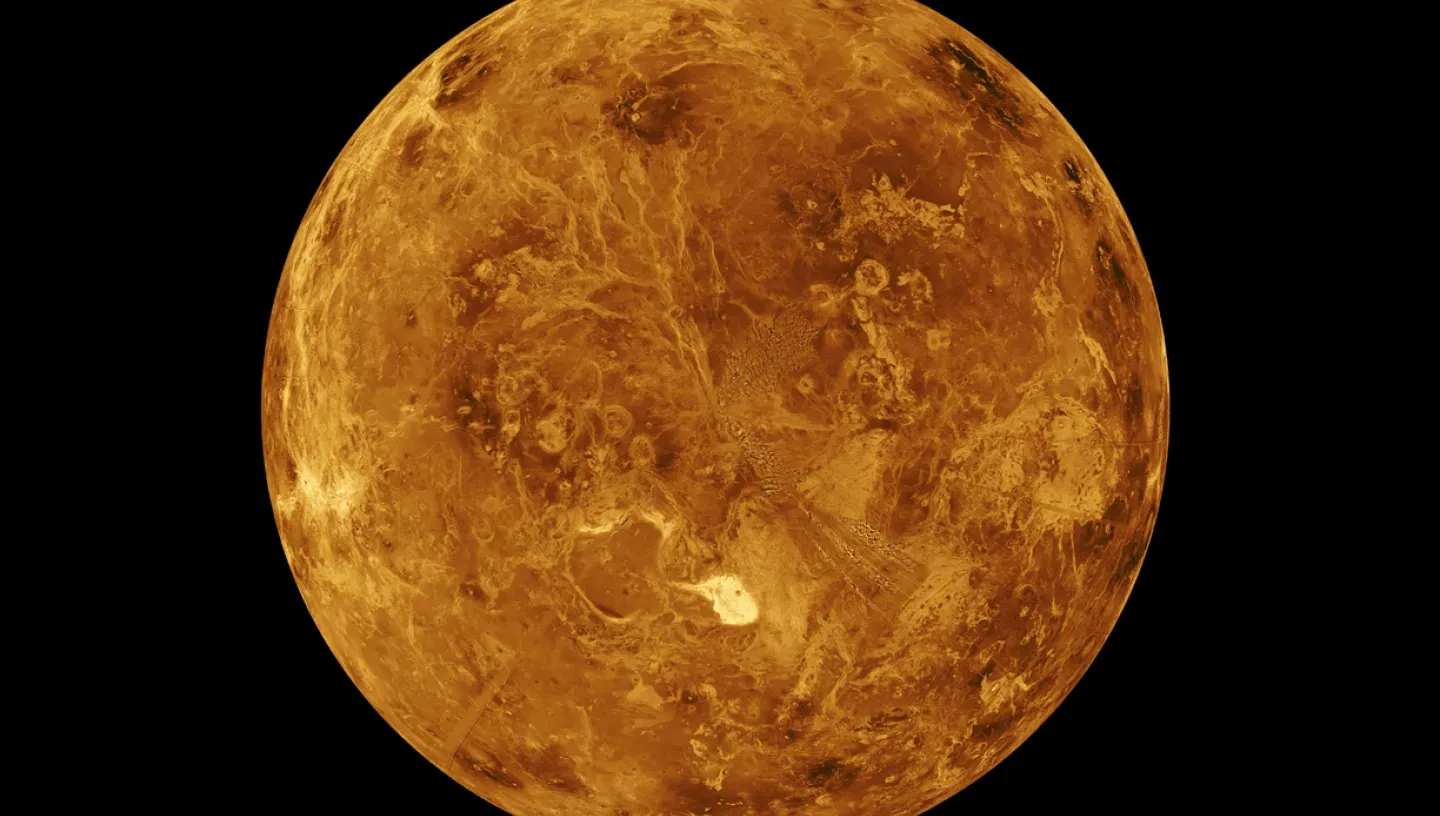

In the past, scientists thought that Venus was very like Earth because of its similar size and distance from the Sun.

This idea was shattered in the 1960s when the Mariner 2 spacecraft uncovered Venus’ hostile environment. Thick, yellowish clouds, made out of sulphuric acid, surround the planet and trap heat on its surface. This makes Venus the hottest planet in the Solar System, with temperature close to 500 degrees Celsius.

The pressures on the surface are around 90 times greater than those of the Earth and are high enough to crush the human body.

Even though the conditions on the surface of the planet are harsh, the temperatures are milder at higher altitudes, as well as the pressure being more similar to Earth’s.

Some scientists have hypothesised that microorganisms or other types of aerial life may exist in the upper atmosphere, high in Venus’ clouds.

What is Phosphine?

Phosphine is a gas made from phosphorus and hydrogen.

It can be found in gas-giant planets in our Solar System, like Jupiter and Saturn, produced by chemical reactions occurring deep inside these planets.

However, it is more difficult to form this gas in the atmospheres of rocky planets in our Solar System, as they experience lower temperatures and pressures than the gas-giants.

Phosphine gas is found on Earth, but it is mainly a product of life, coming either from human industrial activity or from microbes.

The discovery of phosphine gas in the clouds of Venus could, therefore, point to life in the upper atmosphere of the planet.

How was the phosphine gas found?

Phosphine was observed in Venus’ atmosphere by two independent telescopes, the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii and the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) in Chile.

Looking like large satellite dishes, both telescopes operate in longer wavelengths than the human eye can see.

The two telescopes observed phosphine in absorption. This means that a small amount of sunlight reflecting off Venus’ clouds was absorbed by phosphine gas in its atmosphere.

What does this mean?

The amount of phosphine gas in the atmosphere of Venus is relatively low - only twenty molecules in every billion are phosphine.

However, models in this study show that natural chemical processes, from things like sunlight, volcanoes or lightning on Venus, cannot explain the phosphine gas in Venus’ clouds.

The team expect that phosphine comes from either an unknown non-biological process on the planet or from life in the atmosphere.

What next?

There are many unknowns at this point and more investigation must be done before the presence of life can be confirmed on Venus. For instance, studying the atmosphere directly with spacecraft.

Additionally, the clouds surrounding Venus are nearly entirely made up of sulphuric acid and create conditions too harsh for any known form of life on Earth.

Even so, this is an exciting time for astronomy, in particular for understanding our Solar System and the possibilities for life in other places.

If life has formed on Venus independently from Earth, then it is likely that life will be far more common than previously imagined.

With over 4000 detected exoplanets - planets found outside our Solar System - and, no doubt, many more that astronomers have yet to detect, the quest to find life elsewhere in the Universe has reached a compelling new stage.

By Dr Emily Drabek-Maunder, astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich and co-author of the recent discovery of phosphine in the clouds of Venus, ‘Phosphine Gas in the Cloud Decks of Venus’, in Nature Astronomy