Set against the white walls of the Queen’s Closet in the Queen’s House, a trio of photographic portraits draws in the eye. This new acquisition is Kingdom of this World: Triptych by Leah Gordon, a series of reimagined historical engravings that explore issues including enslavement, class struggle, industrialisation and rebellion.

Created in 2019, the artwork takes inspiration from Alejo Carpentier’s historical novel The Kingdom of This World, which tells the story of Haiti before, during and after the revolution of 1791-1804. “Possibly one of the most important and overlooked revolutions of the world, the Haitian Revolution has been all but written out of Western history,” Gordon explains.

The legacies of this pivotal event have informed her artistic practice. A contemporary artist and curator, Gordon explores the interconnections between the Caribbean plantation system, transatlantic slavery and the creation of the British working class.

From the creative process to maritime influences, she speaks to Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich, about her work.

Can you tell us about some of the historical prints that inspired Kingdom of this World: Triptych?

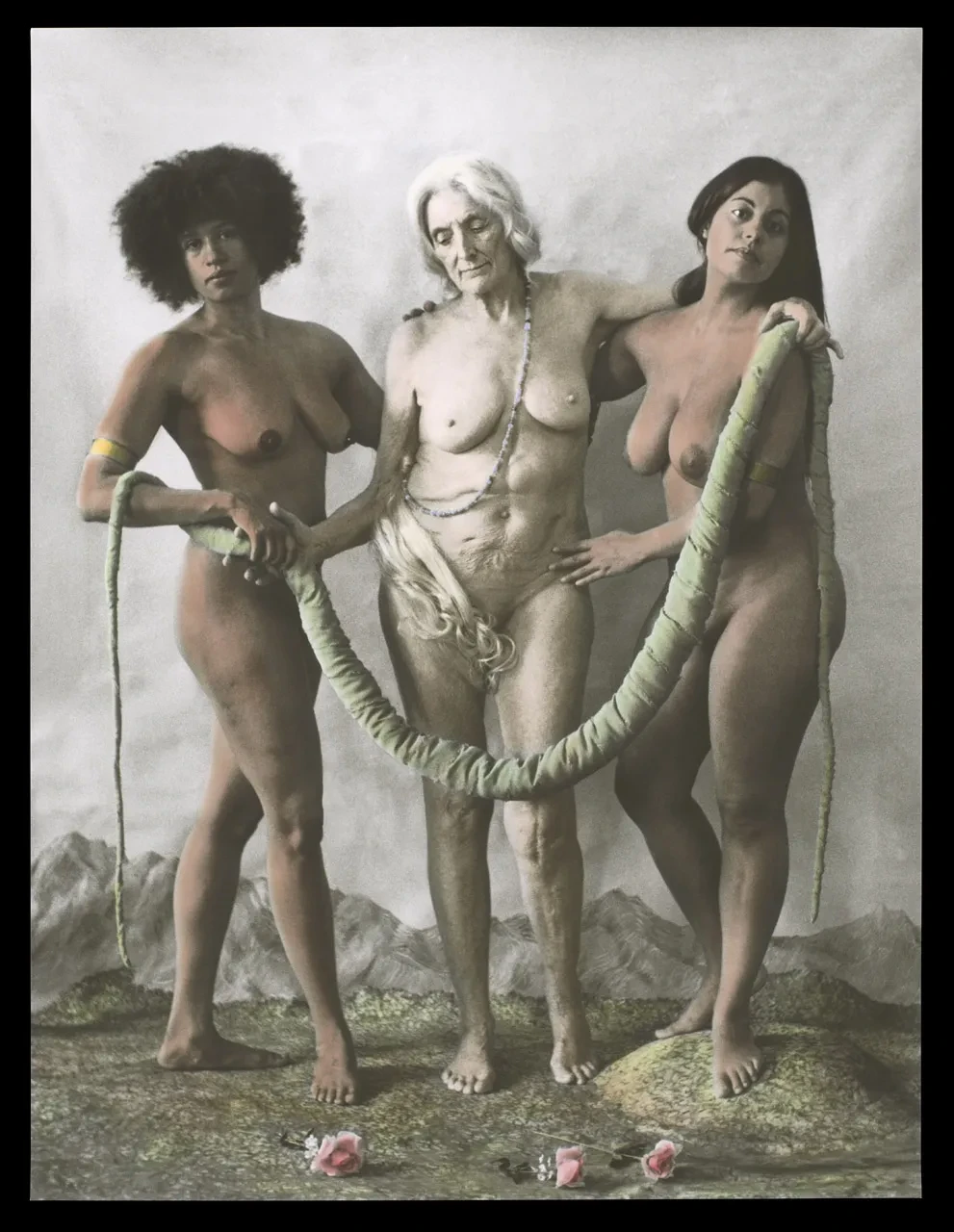

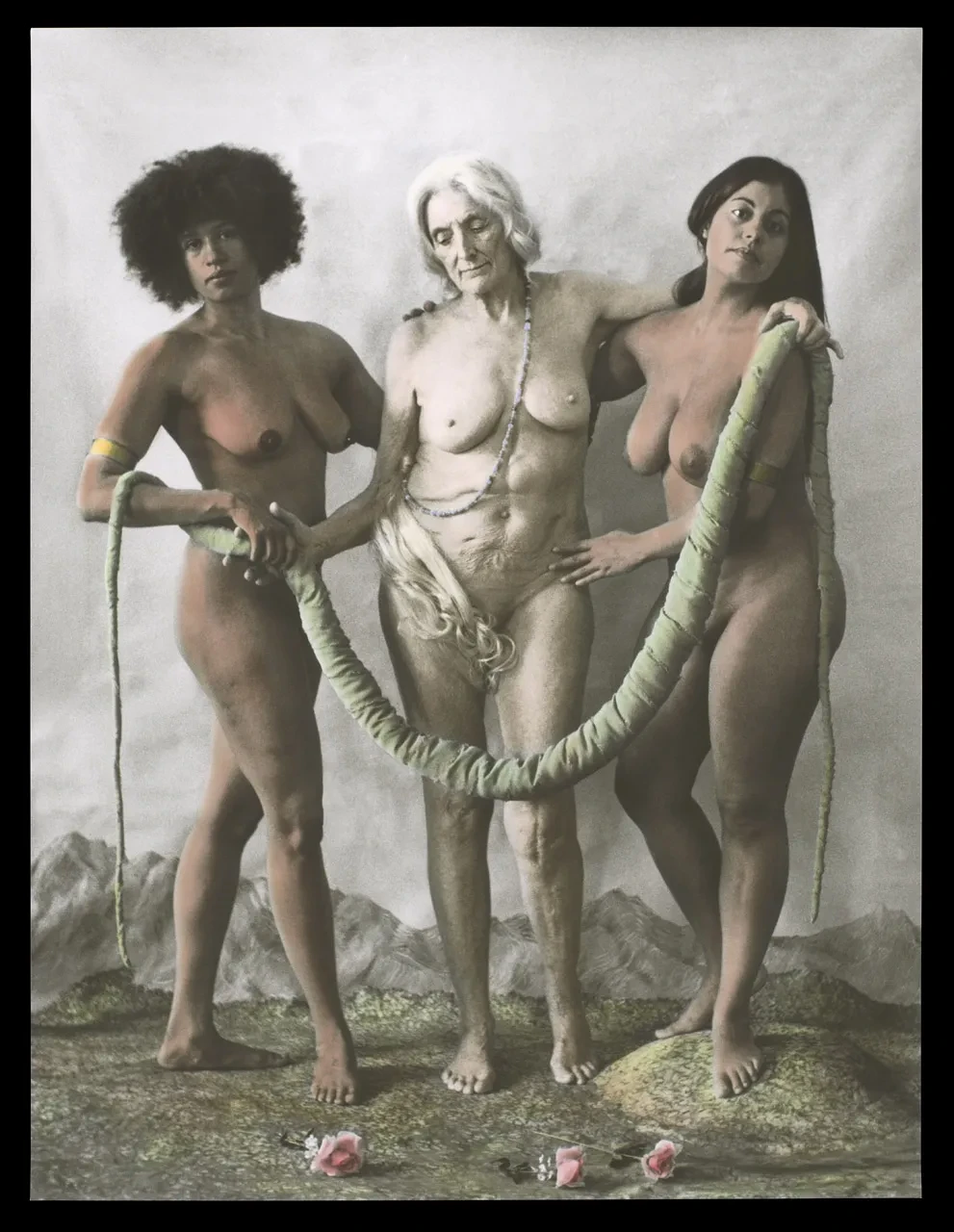

This work is a triptych with a prophetic photographic reconstruction of William Blake’s illustration of ‘Europe Supported by Africa and America’, from a book used by the British abolitionists, at its centre.

This reconstruction – ‘Europe Supported by Africa and the Americas: A Prophesy’ – functions as a stark look at a future where the old economic power balances are shifting and changing. It speculates that perhaps Europe is now a spent and decrepit force.

The central image is flanked by two constructed portraits based upon an illustration from John Thomas Smith’s 1817 book, Vagabondiana, which depicts an injured black British former sailor, Joseph Johnson, begging in Whitechapel’s streets with a ship on his head to denote his former employment. There is a creativity and surreal aspect to this costume, which echoes the end scenes of [the protagonist] Ti Noel’s life in Carpentier’s The Kingdom of This World.

But on another level this book of illustrations by John Thomas Smith, a colleague and friend of William Blake, depict a swathe of British people who chose the life of the vagabond or beggar rather than the intense misery of working in the Northern factories. This is a similar approach to the mental ‘maronaj’ (a Kreyol word based on the word marronage, meaning to run away from enslavement, but also denoting the taking of an intellectual outsider position) of Ti Noel after his years of renewed slavery building the Citadelle Laferrière [located in northern Haiti].

In this project, I have used John Thomas Smith’s illustration as a starting point to construct these two images: one of a black man with a ship on his head in front of the Citadelle (pictured) and the other of a white man with a ship on his head in front of a Welsh iron foundry from the 1800s.

My historical reflections hope to reveal the involved histories between the disenfranchised British working class, the ironic complications of the abolition movement, and the class complexity of the Haitian Revolution.

As well as addressing complex historical issues, how does Kingdom of this World: Triptych speak to contemporary concerns?

I believe that revisiting the turbulences of the epochal capitalist accumulations of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – including the colonial plantation system, the enclosures, the industrial revolution and the creation of a European working class – can help people to gather an internationalist understanding of where we find ourselves in the twenty-first century.

I feel that showing an intersectionality between the character of Ti Noel and a worker from one of the first ironworks in Wales was important to depict international horizontal class solidarity, which is paramount in this complex contemporary epoch.

Places – and the connections between places – seem to be important in your work. Can you tell us about the locations featured in Kingdom of this World: Triptych, including Blaenavon and the Citadelle Laferrière? What other places have inspired you?

The Citadelle Laferrière was chosen as a location as it is quite central to Ti Noel’s experience in The Kingdom of This World, as well as in Haiti’s post-revolutionary history.

I had been planning this portrait for some years, even before the commission, and had walked up that path many times, so I already knew my exact vantage point. I also shot a short 8mm film of Claude Saintilus, a good friend and artist from Port-au-Prince and model for this shoot, walking around the Citadelle singing in costume, as if the ghost of Ti Noel is haunting the Citadelle.

I then realised I needed a British location with a large building from the Industrial Revolution that, in some way, mirrored the form and architecture of the Citadelle. This took some image googling around industrial sites. Blaenavon [in South Wales] was perfect as it is a heritage site so therefore access was easy. It mirrored the bulk and brick work of the Citadelle, and I had a good friend, Gus Hutchinson, who lived nearby who was the perfect model (pictured).

Another site that I repeatedly return to is the Price Plantation, just outside Jacmel, a city in Haiti. It has an example of nineteenth-century industrial machinery, a beam engine, which was fabricated near Liverpool and now lies ruined and overgrown, sinking into the earth on the edge of a sugarcane field.

What does your photographic process involve?

Much of my practice involves retelling forgotten histories and I sometimes use constructed photography reimagining recognisable seventeenth- and eighteenth-century illustrations to subvert readings of the past.

This is a valuable tool to allow me to tell stories spanning the past and the present. I research the original illustrations, which are usually strongly bound to the epoch and history to be explored. I choose relevant locations or often commission a backdrop created by the extremely talented artist and collaborator, Marg Duston.

The photographic portraits are taken on black and white film with an old medium format Rolleicord. Sometimes after the film is developed and black and white prints are made, they are then passed to Marg, who hand-tints them using traditional photographic dyes.

Hand-tinting has myriad metaphorical values for me. In the case of Kingdom of this World, it simply visually reflects the look of many eighteenth-century printmaking techniques, such as the colour-relief etching process often used by William Blake, which can bypass the visual modernity of the photographic print.

We are a maritime museum, so I have to ask: how important are maritime themes within your work?

Ellesmere Port, where I was born, is equidistant between Liverpool, a city built upon the slave trade, and Manchester, which was built upon the Industrial Revolution. Ellesmere Port was the last navigable point on the banks of the River Mersey until the Manchester Ship Canal was built, and therefore a port for several canals, including the Ellesmere Canal (hence the name), the Montgomery Canal and an isolated section of the Shropshire Union Canal. So maritime themes are quite pertinent for my understanding of the geo-politics of history.

The civic badge of Ellesmere Port depicts a ship to represent seaborne commerce, but decorating the sails is a wheel with cogs, one of the central symbols of the industrial revolution. This represents Ellesmere Port’s dependence on local industrial growth and the river and canals, and its significant situation, positioned between these two capital-producing British metropoles.

I made a short film-essay in 2005 about the links between the Thames and the slave trade. More slave boats left via the Thames than from Bristol, but this history is obscured as London’s economic roots are more complex and varied than Bristol and Liverpool, often seen as the only culprits.

The film consists of a journey upstream from Silvertown to London Bridge, passing and commenting on Greenwich at one point, as well as a passage through time. It is a meditation upon rivers, expressing the tensions between their economic, physical and spiritual force.